Royal Patronages of UK Charities: What Are They, Who Gets Them, and Do They Help?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen's Call to Arms! | Sunshine Coast Daily

10/2/2020 YOUR STORY: Queen's Call to Arms! | Sunshine Coast Daily YOUR STORY: Queen's Call to Arms! by GEORGE_HELON 2 14th Sep 2020 10:37 AM Just before his eldest daughter Catherine Middleton married His Royal Highness Prince William, the future Duke of Cambridge on 29 April 2011 in Westminster Abbey, Michael Middleton was granted a coat of arms by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II as a personal gift. On 25 May 2018 Meghan Markle, now the Duchess of Sussex was granted a coat of arms in her own right by the Queen; but in Meghan's case - and partly because of her unruly clan - the privilege extended neither to her father, nor her family. By Letters Patent issued under Crown authority, I GEORGE WILLIAM HELON Esquire of Toowoomba have just been granted a coat of arms, crest, badge and the exemplification of a standard by Her Majesty's College of Arms in London (College Reference: Grants 23/2019). Her Majesty the Queen is the 'Fount of Honour' from whom all titles, grants of arms, orders of chivalry and honours are conferred; they are Our Sovereign's gift and prerogative. Under English heraldic law, a coat of arms and armorial ensigns can be granted to persons of eminence or good standing in national or local life and for exceptional service to society at large. A grant of arms confers upon a person and his or her legitimate descendants the exclusive right to bear a particular coat of arms or armorial bearings in perpetuity. Contrary to what some may have read on the internet and believe, there is no such thing as a coat of arms for a particular surname; coats of arms belong to specific individuals, their families and descendants. -

THE PRINCE of WALES and the DUCHESS of CORNWALL Background Information for Media

THE PRINCE OF WALES AND THE DUCHESS OF CORNWALL Background Information for Media May 2019 Contents Biography .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seventy Facts for Seventy Years ...................................................................................................... 4 Charities and Patronages ................................................................................................................. 7 Military Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Duchess of Cornwall ............................................................................................................ 10 Biography ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Charities and Patronages ............................................................................................................... 10 Military Affiliations ........................................................................................................................ 13 A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the "Our Planet" premiere, Natural History Museum, London ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Address by HRH The Prince of Wales at a service to celebrate the contribution -

Equerries to The.Duke of Gloucester, ' :...\ , 'Edmund Currey, Esq

[ 2900 ] Equerries to the.Duke of Gloucester, ' :...\ , 'Edmund Currey, Esq. Lieut. Col. Samuel Higgins. ,/, Equerries to the Duke of Cambridge, •... Colonel Keat, Major-General Sir James Lyon, K. C'. B. Equerries to the Duke of Sussex, Henry Fredericlc Stephenson, Esq. "Major Perkins Magra. Equerries to the Duke of Cumberland, ' .- Colonel Charles Wade Thornton, Lieutenant-General Henry Wynyard, General Vyse> Equerries to the Duke of Kent, Captain Conran, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry W. Carr, K. C. B. Major-General Sir George Anson, K. C. B. Lieutenant-General Wetherall. Equerry to the Duke of York, Charles Culling Smith, Esq. • " Equerries to the Prince Regent, ... Charles Quentin, Esq. Major-General Sir Richard Hussey Vivian, K. C. B. Sir William Cougreve, Bart. Clerk-Marshal and First Equerry to the Prince Regent, Lieutcnant-General F. T. Hammond. Quarter-Master-General, Adjutant-General, Maj. Gen. Sir J. Willoughby Gordon, Bart. K. C. B. Lieu] . Sir Harry Calvert, Bart. G. C. 15. Equerries to the King. Lieutenant-General William Wynyard. Lieutenant-General Sir Brent Spencer, G. C. B. General Cartvvright. General Gwyn. Clerk-Marshal and First Equerry. General Robert Manners. Gentlemen Ushers of the Privy Chamber to His Majesty, John Hale, Esq. Sir Robert Chester, Knt. .T. Hatton, Esq. W. Masten, Esq. Officers of the Duehy of Cornwall, viz. Solicitor General, William Harrison, Esq. Auditor, Receiver-General, Sir William Kn.ighton, Bart. • The Right Honourable Lord William Gordon. Lord Warden of the Stannaries, <'. The Earl of Yarmouth. Grooms of the Bedchamber to His Majesty, Admiral Sir George Campbell, K. C.B. Lieut.-Col. the Hon. Henry King. -

Monarchy in Scotland | the Edinburgh Legal History Blog

Edinburgh Research Explorer Monarchy in Scotland Citation for published version: Cairns, JW, Monarchy in Scotland, 2013, Web publication/site, Edinburgh Legal History Blog. <http://www.elhblog.law.ed.ac.uk/2013/07/23/monarchy-in-scotland/> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publisher Rights Statement: © Cairns, J. (Author). (2013). Monarchy in Scotland. Edinburgh Legal History Blog. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Monarchy in Scotland | The Edinburgh Legal History Blog http://www.elhblog.law.ed.ac.uk/2013/07/23/monarchy-in-scotland/ The Edinburgh Legal History Blog Monarchy in Scotland Posted on 23/07/2013 by John Cairns The birth of a Prince to the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge on 22 July calls for some reflection in a Legal History Blog, particularly one based in Scotland, with which our British Royal family has such close links, both ancient and recent. Of course, the Duke’s and Duchess’s studies at the University of St Andrews are well known; less well known is that the Duchess’s sister, “Pippa” Middleton, studied at your blogger’s University of Edinburgh. -

Royal Foundation's Annual Report

Company Registration No. 7033553 Charity Registration No. 1132048 The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge (formerly The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and The Duke and Duchess of Sussex) Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2019 The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge (formerly The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and The Duke and Duchess of Sussex) Company Registration No. 7033553 Contents Page Principals and Members, Officers and Professional Advisers 1 Letter from the Chair of the Board 2 Trustees' report - incorporating the Directors' report for Companies Act purposes 4 Independent Auditor's report 16 Consolidated statement of financial activities 19 Charity statement of financial activities 20 Consolidated and charity balance sheet 21 Consolidated and charity cash flow statement 22 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 23 The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge (formerly The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and The Duke and Duchess of Sussex) Company Registration No. 7033553 Principals and Members TRH The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge Trustees Sir Keith Mills, GBE, DL – Chairman Tessa Green, CBE Edward Harley, OBE, DL (resigned 18 September 2019) Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton, LVO, MBE, DL Charles Mindenhall Guy Monson (appointed 18 September 2019, resigned 10 December 2019) Simon Patterson Lady Pinsent Claire Wills Ex Officio Trustees Simon Case, CVO (appointed 8 August 2019) -

1 the Public Life of a Twentieth Century Princess Princess Mary Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood Wendy Marion Tebble

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SAS-SPACE 1 The Public Life of a Twentieth Century Princess Princess Mary Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood Wendy Marion Tebble, Institute of Historical Research Thesis submitted for Degree of Master of Philosophy, 2018 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 7 Acronyms 8 Chapters 9 Conclusion 136 Bibliography 155 3 Abstract The histiography on Princess Mary is conspicuous by its absence. No official account of her long public life, from 1914 to 1965, has been written and published since 1922, when the princess was aged twenty-five, and about to be married. The only daughter of King George V, she was one of the chief protagonists in his plans to include his children in his efforts to engage the monarchy, and the royal family, more deeply and closely with the people of the United Kingdom. This was a time when women were striving to enter public life more fully, a role hitherto denied to them. The king’s decision was largely prompted by the sacrifices of so many during the First World War; the fall of Czar Nicholas of Russia; the growth of socialism; and the dangers these events may present to the longevity of the monarchy in a disaffected kingdom. Princess Mary’s public life helps to answer the question of what role royal women, then and in the future, are able to play in support of the monarchy. It was a time when for the most part careers of any kind were not open to women, royal or otherwise, and the majority had yet to gain the right to vote. -

SCHEDULE of JOURNEYS COSTING £10,000 OR MORE Year Ended 31St March 2015

SCHEDULE OF JOURNEYS COSTING £10,000 OR MORE Year Ended 31st March 2015 Household Method Date Itinerary Cost (£) of travel The Queen and The Duke of Charter 3 Apr NHT – Rome - NHT 27,298 Edinburgh Visit The President of the Italian Republic and Mrs. Napolitano at Quirinale Palace. Visit The Sovereign of the State of the Vatican City (His Holiness Pope Francis). The Prince of Wales Royal 8-9 Apr Windsor - Oxenholme 17,772 Train Visit J36 Rural Auction Centre. Attend the launch of the Tourism Initiative. Visit the Northern Fells Group Rural Revival Initiative. Visit Hospice at Home West Cumbria. The Queen and The Duke of Royal 16-17 Apr Windsor - Blackburn 17,551 Edinburgh Train Attend the Maundy Service at which Her Majesty distributed the Royal Maundy. Join representatives of the Cathedral, the Diocese and the Royal Almonry at a Reception at Blackburn Rovers Football Club, Ewood Park. Luncheon at the Club by the Mayor of Blackburn-with-Darwen. Staff (Prince Henry of Wales) Scheduled 27 Apr - 1 LHR – Sao Paulo - Santiago - Brasilia – 19,304 Flight May Belo Horizonte – Sao Paul – LHR Reconnaissance tour for Prince Henry of Wales visit to Brazil and Chile. The Queen and The Duke of Royal 29-30 Apr Windsor - Haverfordwest - Ystrad Mynach 30,197 Edinburgh Train Visit Cotts Equine Centre, Cotts Farm, Narberth. Tour the equine hospital, view the "Knock Down and Recovery Suite", Operating Theatre, Nurses' Station and horses, and meet members of the veterinary team, grooms and other staff members. Visit Princes Gate Spring Water, New House Farm, Narberth. Luncheon at Picton Castle, Haverfordwest by Pembrokeshire County Council. -

Some Observations on the Queen, the Crown, the Constitution, and the Courts Warren J Newman*

Some Observations on the Queen, the Crown, the Constitution, and the Courts Warren J Newman* Canada was established in 1867 as a Dominion Le Canada fut fondé en 1867 comme un under the Crown of the United Kingdom, with dominion sous la Couronne du Royaume-Uni, a Constitution similar in principle to that of the avec une constitution semblable en principe à celle United Kingdom. Th e concept of the Crown has du Royaume-Uni. Le concept de la Couronne evolved over time, as Canada became a fully a évolué au fi l du temps, au fur et à mesure independent state. However in 2017, Canada que le Canada est devenu un état entièrement remains a constitutional monarchy within what indépendant, mais en 2017 le Canada demeure is now the Commonwealth, and the offi ces of the une monarchie constitutionnelle à l’intérieur Queen, the Governor General, and the provincial de ce qui est maintenant le Commonwealth et Lieutenant Governors are constitutionally les fonctions de la Reine, du gouverneur général entrenched. Indeed, in elucidating the meaning et des lieutenants-gouverneurs des provinces ont of the Crown, an abstraction that naturally été constitutionnalisées. En fait, en élucidant le gives rise to academic debate and divergent sens de la Couronne, une abstraction qui donne perspectives, it is important not to lose sight of naturellement lieu à des débats théoriques et des the real person who is Her Majesty, given the points de vue divergents, il est important de ne importance that our constitutional framework pas perdre de vue la vraie personne qui est Sa attaches to her role, status, and powers. -

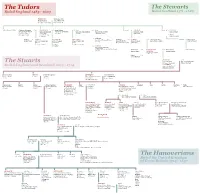

The Stuarts the Tudors the Hanoverians

The Tudors The Stewarts Ruled England 1485 - 1603 Ruled Scotland 1371 - 1603 HENRY VII = Elizabeth of York King of England dau. of Edward IV, (b. 1457, r. 1485-1509) King of England Arthur Prince of Wales Catherine of Aragon (1) = HENRY VIII = (2) Anne Boleyn = (3) Jane = (4) Anne Margaret = JAMES IV Mary = (1) LOUIS XII dau of FERDINAND V. King of England and dau of Earl of Wiltshire dau of Sir John Seymour dau of Duke of Cleves King of Scotland King of France first King of Spain (from 1541) (ex. 1536) (d. 1537) (div 1540 d.1557) (1488-1513) (div 1533. d. 1536.) Ireland (b. 1491, = (2) Charles r. 1509-47) Duke of Suffolk = (5) Catherine (1) (2) Phillip II = MARY I ELIZABETH I EDWARD VI dau of Lord Edmund Howard Madeline = JAMES V = Mary of Lorraine Frances = Henry Grey King of Spain Queen of England and Queen of England King of England and (ex 1542) dau of FRANCIS I. King of Scotland dau of Duke of Guise Duke of Suffolk Ireland and Ireland Ireland King of France (d. 1537) (1513-1542) (b. 1516, r. 1553-8) (b. 1533, r. (b. 1537, r. 1547-53) 1558-1603) = (6) Catherine dau of Sir Thomas Parr (HENRY VIII was her third husband) FRANCIS II (1) = MARY QUEEN = (2) Henry Stuart Lady Jane Grey (d. 1548) King of France OF SCOTS Lord of Darnley (1542-1567. ex 1587) James (3) = Earl of Bothwell JAMES VI = Anne The Stuarts King of Scotland dau. of FREDERICK II, (b. 1566, r. 1567-1625) King of Denmark and JAMES I, Ruled England and Scotland 1603 - 1714 King of England and Ireland (r. -

What's in a Title?

BEST OF BRITAIN WHAT’S IN A TITLE? A QUICK GUIDE TO THE ROYALS Queen Elizabeth II is our longest reign - Charles I was executed by the people in Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. ing monarch and at 91-years-old, is also 1649, leading to 11 years of Britain as a There are many official titles in the the world’s oldest living monarch. She republic, and Charles II ’s extravagant royal family, and it is tradition that Royal was not destined to be queen. In fact, lifestyle meant that he was not always Dukedoms are the highest-ranking hon - she was already 10-years-old when her well behaved! our. Only the eldest son of the sover - uncle, Edward VIII, abdicated after a Who can be a King, Queen or Princess? eign is entitled to the Dukedoms of short reign because of his love for di - Cornwall and Rothesay; these are held vorcee and US citizen Wallis Simpson, Camilla, Prince Charles’ wife, has the by Prince Charles who is addressed as resulting in Elizabeth’s father becoming title the Duchess of Cornwall and as the the Duke of Rothesay when in Scotland. King George VI. wife of the Prince of Wales, could also The second son of the monarch is usu - The Queen’s two birthdays be called Princess of Wales. She decided ally given the title Duke of York, in the not to take this title because it was current case this is Prince Andrew. The As a British monarch, Queen Elizabeth clearly connected with Charles’ first Queen’s third son is officially known as is also lucky enough to enjoy two birth - wife, Diana. -

Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 12-2017 "Something Must Be Done!": Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy Allyse C. Zajac Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Zajac, Allyse C., ""Something Must Be Done!": Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy" (2017). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 118. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOMETHING MUST BE DONE!”: EDWARD VIII’S ABDICATION AND THE PRESERVATION OF THE BRITISH MONARCHY Allyse Zajac Salve Regina University Department of History Senior Thesis Dr. Leeman December 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the McGinty family for creating the John E. McGinty Fund in History. Thanks to the John E. McGinty Fund, I was able to conduct research at both the Lambeth Palace Library and Parliamentary Archives in London. The documents I had access to at both of these archives have been fundamental to my research and I would not have had the opportunity to view them without the McGintys’ generosity. Zajac 1 To the average Englishman, 1936 appeared to be a good year. -

THE BRITISH EMPIRE. the British Empire Consists of :- I

THE BRITISH EMPIRE. The British Empire consists of :- I. THE uNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. II. INDIA, THE CoLONIES, PRoTECTORATES, AND DEPENDENCIES. Reigning King and Emperor. Edward VII., born Nov. 9, 1841, son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; married March 10, 1863, to Princess Alexandra, eldest daughter of King Christian IX. of Denmark; succeeded to the crown on the death of his mother, January 22, 1901. Children of tlte King. I. George Frederick, Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and York, Duke of Rothsay in Scotland, the heir-apparent, born June 3, 1865; married July 6, 1893, to Victoria Mary, daughter of the Duke of Teck. Offspring :-(1) Edward Albert, born June 23, 1894; (2) Albert Frederick, born December 14, 1895; (3) Victoria Alexandra, born April 25, 1897; (4) Henry William, born March 31, 1900; (5) George Edward, born December 20, 1902. II. Princess Louise, born February 20, 1867; married July 27, 1889, to the Duke of Fife. Offspring :-(1) Alexandra Victoria, born May 17, 1891; (2) Maud Alexandra, born April 3, 1893. III. Princess VictO'I'ia Alexandra, born July 6, 1868. IV. Princess Maud Charlotte, born November 26, 1869; married July 22, 1896, to Prince Karl of Denmark. Brother and Sisters of the King. Princess Victoria (Empress Frederick), born Nov. 21, 1840; married, Jan. 25, 1858, to Prince Friedrich Wilhelm (Friedrich I. of Germany), eldest son of '\Tilhelm 1., German Emperor and King of Prussia; widow, June 15, 1888; died August 5, 1901. Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, born August 6, 1844 ; became Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, August 22, 1893 ; married January 23, 1874, to the Grand Duchess :Marie of Russia, daughter of the Emperor Alexander II.; died Jtlly 30, 1900, His surviving children are: (1) Marie, born Ocf, B 2 4 'fHE BRITISH EMPIRE :-UNITED KINGDOM 29, 1875; married Jan.