Rules of Royal Succession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOI Letter Template

Royal, Ceremonial & Honours Unit Protocol Directorate Foreign and Commonwealth Office King Charles Street London SW1A 2AH Website: https://www.gov.uk 22 February 2016 Dear FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 2000 REQUEST REF: 0082-16 Thank you for your email of 23 January asking for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. You asked: “I would be pleased to receive information and correspondence held by the FCO between and within the offices of FCO ministers, FCO protocol and Royal matters unit department concerning the rules and regulations pertaining to the use of titles of honour, such as knighthoods, granted by The Queen or her official representatives in right of another Commonwealth Realm, to UK and dual nationals of the Queen’s Commonwealth realms, any correspondence on the changing of such rules and regulations for UK nationals and dual UK nationals who are also a national of another Commonwealth Realm.” We can confirm that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) does hold information relevant to your request. Some of the information that we hold which is relevant to your request is, in our view, already reasonably accessible to you. Under section 21 of the Act, we are not required to provide information in response to a request if it is already reasonably accessible to the applicant. Responses to Parliamentary Questions on this subject are available to view at www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written- questions-answers using the keyword “knighthoods”. However, other information and correspondence on the use of titles of honours has been withheld as it is exempt under section 37(1)(a) of the Freedom of Information Act (FOI) – communications with, or on behalf of, the Sovereign. -

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Albion Full Cast Announced

Press release: Thursday 2 January The Almeida Theatre announces the full cast for its revival of Mike Bartlett’s Albion, directed by Rupert Goold, following the play’s acclaimed run in 2017. ALBION by Mike Bartlett Direction: Rupert Goold; Design: Miriam Buether; Light: Neil Austin Sound: Gregory Clarke; Movement Director: Rebecca Frecknall Monday 3 February – Saturday 29 February 2020 Press night: Wednesday 5 February 7pm ★★★★★ “The play that Britain needs right now” The Telegraph This is our little piece of the world, and we’re allowed to do with it, exactly as we like. Yes? In the ruins of a garden in rural England. In a house which was once a home. A woman searches for seeds of hope. Following a sell-out run in 2017, Albion returns to the Almeida for four weeks only. Joining the previously announced Victoria Hamilton (awarded Best Actress at 2018 Critics’ Circle Awards for this role) and reprising their roles are Nigel Betts, Edyta Budnik, Wil Coban, Margot Leicester, Nicholas Rowe and Helen Schlesinger. They will be joined by Angel Coulby, Daisy Edgar-Jones, Dónal Finn and Geoffrey Freshwater. Mike Bartlett’s plays for the Almeida include his adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s Vassa, Game and the multi-award winning King Charles III (Olivier Award for Best New Play) which premiered at the Almeida before West End and Broadway transfers, a UK and international tour. His television adaptation of the play was broadcast on BBC Two in 2017. Other plays include Snowflake (Old Fire Station and Kiln Theatre); Wild; An Intervention; Bull (won the Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); an adaptation of Medea; Chariots of Fire; 13; Decade (co-writer); Earthquakes in London; Love, Love, Love; Cock (Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); Contractions and My Child Artefacts. -

Court of Versailles: the Reign of Louis XIV

Court of Versailles: The Reign of Louis XIV BearMUN 2020 Chair: Tarun Sreedhar Crisis Director: Nicole Ru Table of Contents Welcome Letters 2 France before Louis XIV 4 Religious History in France 4 Rise of Calvinism 4 Religious Violence Takes Hold 5 Henry IV and the Edict of Nantes 6 Louis XIII 7 Louis XIII and Huguenot Uprisings 7 Domestic and Foreign Policy before under Louis XIII 9 The Influence of Cardinal Richelieu 9 Early Days of Louis XIV’s Reign (1643-1661) 12 Anne of Austria & Cardinal Jules Mazarin 12 Foreign Policy 12 Internal Unrest 15 Louis XIV Assumes Control 17 Economy 17 Religion 19 Foreign Policy 20 War of Devolution 20 Franco-Dutch War 21 Internal Politics 22 Arts 24 Construction of the Palace of Versailles 24 Current Situation 25 Questions to Consider 26 Character List 31 BearMUN 2020 1 Delegates, My name is Tarun Sreedhar and as your Chair, it's my pleasure to welcome you to the Court of Versailles! Having a great interest in European and political history, I'm eager to observe how the court balances issues regarding the French economy and foreign policy, all the while maintaining a good relationship with the King regardless of in-court politics. About me: I'm double majoring in Computer Science and Business at Cal, with a minor in Public Policy. I've been involved in MUN in both the high school and college circuits for 6 years now. Besides MUN, I'm also involved in tech startup incubation and consulting both on and off-campus. When I'm free, I'm either binging TV (favorite shows are Game of Thrones, House of Cards, and Peaky Blinders) or rooting for the Lakers. -

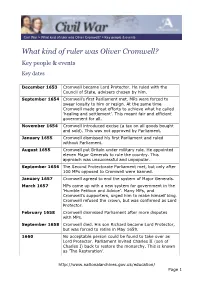

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Columbia Law Review

COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 99 DECEMBER 1999 NO. 8 GLOBALISM AND THE CONSTITUTION: TREATIES, NON-SELF-EXECUTION, AND THE ORIGINAL UNDERSTANDING John C. Yoo* As the globalization of society and the economy accelerates, treaties will come to assume a significant role in the regulation of domestic affairs. This Article considers whether the Constitution, as originally understood, permits treaties to directly regulate the conduct of private parties without legislative implementation. It examines the relationship between the treaty power and the legislative power during the colonial, revolutionary, Framing, and early nationalperiods to reconstruct the Framers' understandings. It concludes that the Framers believed that treaties could not exercise domestic legislative power without the consent of Congress, because of the Constitution'screation of a nationallegislature that could independently execute treaty obligations. The Framers also anticipatedthat Congress's control over treaty implementa- tion through legislation would constitute an importantcheck on the executive branch'spower in foreign affairs. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... 1956 I. Treaties, Non-Self-Execution, and the Internationalist View ..................................................... 1962 A. The Constitutional Text ................................ 1962 B. Globalization and the PoliticalBranches: Non-Self- Execution ............................................. 1967 C. Self-Execution: The InternationalistView ................ -

What Goes up Must Come Down: Integrating Air and Water Quality Monitoring for Nutrients Helen M Amos, Chelcy Miniat, Jason A

Subscriber access provided by NASA GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CTR Feature What Goes Up Must Come Down: Integrating Air and Water Quality Monitoring for Nutrients Helen M Amos, Chelcy Miniat, Jason A. Lynch, Jana E. Compton, Pamela Templer, Lori Sprague, Denice Marie Shaw, Douglas A. Burns, Anne W. Rea, David R Whitall, Myles Latoya, David Gay, Mark Nilles, John T. Walker, Anita Rose, Jerad Bales, Jeffery Deacon, and Richard Pouyat Environ. Sci. Technol., Just Accepted Manuscript • DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03504 • Publication Date (Web): 19 Sep 2018 Downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org on September 21, 2018 Just Accepted “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. They are posted online prior to technical editing, formatting for publication and author proofing. The American Chemical Society provides “Just Accepted” as a service to the research community to expedite the dissemination of scientific material as soon as possible after acceptance. “Just Accepted” manuscripts appear in full in PDF format accompanied by an HTML abstract. “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been fully peer reviewed, but should not be considered the official version of record. They are citable by the Digital Object Identifier (DOI®). “Just Accepted” is an optional service offered to authors. Therefore, the “Just Accepted” Web site may not include all articles that will be published in the journal. After a manuscript is technically edited and formatted, it will be removed from the “Just Accepted” Web site and published as an ASAP article. Note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the manuscript text and/or graphics which could affect content, and all legal disclaimers and ethical guidelines that apply to the journal pertain. -

Ride-Buyers: Joe and Mark

Ride-Buyers: Joe and Mark This is a long story about two of racing’s filthy rich ride-buyers, Joe Boyer (1890-1924) and Mark Thatcher, but it begins with Boyer’s distant relative William Burroughs, the beat generation’s favorite author, who wrote bandit books like “Junky” and “Naked Lunch,” and spent his life roaming the freak earth from Algiers to Mexico City to New Orleans hanging with three of other great beatniks Dean Moriarty, Sal Paradise, and Carlo Marx (all pseudonyms). Purposely spaced out in his various personas as dope fiend, petty criminal, sexual athlete, and firearms fanatic, Burroughs once played a game of “William Tell” with his wife and, while trying to shoot an apple off her head, missed and blew her brains out. Burroughs’ grandfather was the inventor of the world’s favorite multiplication appliance, the Burroughs Adding Machine, and Joe Boyer’s father was the company’s very own Chief Executive Officer. Yet when William Burroughs died in the late 1990s it was a cultural event in print and on TV; and the last time Joe Boyer, missing since 1924, was ever accorded a tribute was back in 1985, when the Indy 500’s Old Timers club posthumously inducted him into its Hall of Fame. Too bad that the counterculture drug addict and the Brickyard’s richest ride-buyer never hooked up - they’d have made quite a twining. Until the stock market tanked in 1929, the Roaring Twenties was the ultimate decade for enjoying private wealth and privilege, and Joe Boyer benefitted from wealth and privilege alike - A blue-blood of Detroit’s high-society who belonged to every snob country club that upper crust Michigan boasted of, Boyer, upon deciding he had to become a race driver in the Indy 500 as quickly as possible, wasted no time on formalities. -

In the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:43:06AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

17 April 2020

HOUSE OF LORDS BUSINESS 17 April 2020 Contents Tuesday 21 April 2020 at 1.00pm Future Business 2 †Lord Grimstone of Boscobel and Select Committee Reports 7 †Lord Greenhalgh will be introduced. Motions Relating to Delegated Legislation 8 †Business of the House (Virtual Proceedings and Topical Questions for Questions for Short Debate 8 Written Answer) The Lord Privy Seal (Baroness Evans of Bowes Park) to Bills in Progress 13 move that, until further Order– Statutory Instruments in Progress 15 1. The following proceedings of the House may take place as Virtual Committee Sheet 18 Proceedings: Oral Questions, Private Notice Questions, Ministerial Statements, debates (but not decisions) on Statutory Instruments, Questions for Short Debate and motions for debate; 2. The procedure in Virtual Proceedings shall follow, so far as practical, procedure in the House save that– (a) no member may participate unless admitted to the Virtual Proceedings; (b) the order of speaking in Virtual Proceedings shall be facilitated by the Chair; (c) the time allotted for Oral Questions shall be extended to 40 minutes to allow up to 10 minutes for each Oral Question; (d) the time allotted to business in Virtual Proceedings may be varied by unanimous agreement of members taking part in the Virtual Proceedings; and (e) Virtual Proceedings may be adjourned between items or classes of business at the discretion of the Chair; 3. A Virtual Proceeding may take place irrespective of whether the House is sitting that day; 4. A member may table one Topical Question for Written Answer in each week Items marked † are new or have been altered during which the House sits, and it is expected that it will be answered within [I] indicates that the member concerned has five working days; a relevant registered interest.