BIFAO 118 (2018), P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2 Metlife Clinic - Cairo Medical Center 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Metlife Clinic 02 24509800 02 22580672 Hospital Heliopolis Emergency- 39 Cleopatra St. Salah El Din Sq., Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Cleopatra Hospital Gold Outpatient- 19668 Heliopolis Inpatient ( Except Emergency- 21 El Andalus St., Behind Cairo Heliopolis Hospital International Eye Hospital Gold 19650 Outpatient-Inpatient Mereland , Roxy, Heliopolis Emergency- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital San Peter Hospital Green 3 A. Rahman El Rafie St., Hegaz St. 02 21804039 02 21804483-84 Outpatient-Inpatient Emergency- 16 El Nasr st., 4th., floor, El Nozha Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Ein El Hayat Hospital Green 02 26214024 02 26214025 Outpatient-Inpatient El Gedida Cairo Medical Center - Cairo Heart Emergency- 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Silver 02 24509800 02 22580672 Center Outpatient-Inpatient Heliopolis Inpatient Only for 15 Khaled Ibn El Walid St. Off 02 22670702 (10 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital American Hospital Silver Gynecology and Abdel Hamid Badawy St., Lines) Obstetrics Sheraton Bldgs., Heliopolis 9 El-Safa St., Behind EL Seddik Emergency - Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Nozha International Hospital Silver Mosque, Behind Sheraton 02 22660555 02 22664248 Inpatient Only Heliopolis, Heliopolis 91 Mohamed Farid St. El Hegaz Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Al Dorrah Heart Care Hospital Orange Outpatient-Inpatient 02 22411110 Sq., Heliopolis 19 Tag El Din El Sobky st., from El 02 2275557-02 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Nozha st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 22738232 2 Samir Mokhtar st., from Nabil El 02 22681360- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Wakad st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 01225320736 Dr. -

ATM Branch Branch Address Area Gameat El Dowal El

ATM Branch Branch address Area Gameat El Dowal Gameat El Dowal 9 Gameat El-Dewal El-Arabia Mohandessein, Giza El Arabeya Thawra El-Thawra 18 El-Thawra St. Heliopolis, Heliopolis, Cairo Cairo 6th of October 6th of October Banks area - industrial zone 4 6th of October City, Giza Zizenia Zizenia 601 El-Horaya St Zizenya , Alexandria Champollion Champollion 5 Champollion St., Down Town, Cairo New Hurghada Sheraton Hurghada Sheraton Road 36 North Mountain Road, Hurghada, Red Sea Hurghada, Red Sea Mahatta Square El - Mahatta Square 1 El-Mahatta Square Sarayat El Maadi, Cairo New Maadi New Maadi 48 Al Nasr Avenu New Maadi, Cairo Shoubra Shoubra 53 Shobra St., Shoubra Shoubra, Cairo Abassia Abassia 111 Abbassia St., Abassia Cairo Manial Manial Palace 78 Manial St., Cairo Egypt Manial , Cairo Hadayek El Kobba Hadayek El Kobba 16 Waly El-Aahd St, Saray El- Hdayek El Kobba, Cairo Hadayek Mall Makram Ebeid Makram Ebeid 86, Makram Ebeid St Nasr City, Cairo Abbass El Akkad Abbass El Akkad 20 Abo El Ataheya str. , Abas Nasr City, Cairo El akad Ext Tayaran Tayaran 32 Tayaran St. Nasr City, Cairo House of Financial Affairs House of Financial Affairs El Masa, Abdel Azziz Shenawy Nasr City, Cairo St., Parade Area Mansoura 2 El Mohafza Square 242 El- Guish St. El Mohafza Square, Mansoura Aghakhan Aghakhan 12th tower nile towers Aghakhan, Cairo Aghakhan Dokki Dokki 64 Mossadak Street, Dokki Dokki, Giza El- Kamel Mohamed El_Kamel Mohamed 2, El-Kamel Mohamed St. Zamalek, Cairo El Haram El Haram 360 Al- Haram St. Haram, Giza NOZHA ( Triumph) Nozha Triumph.102 Osman Ebn Cairo Affan Street, Heliopolis Safir Nozha 60, Abo Bakr El-Seddik St. -

Annaulreport MISR BANK 2004-2005.Pdf

Mr. Mohamed Kamal El Din Barakat Chairman During the fiscal year 2004/2005, the Egyptian government undertook significant structural reforms to the financial and monetary policies that led to an increase in the GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate to 5.1% compared to 4.2% in the previous year as well as a reduction of the inflation rate to 4.7%. Furthermore, the foreign exchange markets witnessed stability and the monetary reserves of foreign currencies increased to more than $20 Billion. This improvement was reflected upon all market sectors including banking. Consequently, it impacted Banque Misr's financial achievements for this year where total assets had grown by 17.3% to reach L.E 106.8 billion. As for the deposits, they grew by 16.3% to reach L.E 93.2 Billion and the shareholders' equity increased by 2.6% to reach L.E 3.5 Billion. Concerning loans, the total loans portfolio grew by 3.8% to reach L.E 37.8 billion. Furthermore, the bank continued its support for small and micro finance projects by offering credit facilities engaging higher employment rates for economy support. The financial investments increased by 26% to reach L.E. 39.1 Billion. In this context, the Bank's newly introduced investment fund with daily current revenue (day by day account) was highly accepted by the customers. This was reflected by the increase of its net value from L.E. 200 Million on its issuance date during August 2004 to reach more than L.E. 2 Billion by the end of July 2005, the total profits before provisions and taxes increased by 74.3% to reach L.E. -

Egypt: Specific Appendixes

SPECIFIC APPENDIXES PRESENTATION Reader will find hereafter appendixes that do not appear in the paper version of our pamphlet. They consist in: General chronology, from January 1st to May 7th 2011, List of army-owned factories, Detailed strikes chronology, from February to May. CHRONOLOGY January Jan 1 Attack against a Coptic church in Alexandria. Confrontation between Copts and Police the same day in Alexandria. Jan 2 Confrontation between Copts and Police in Cairo Jan. 12 Egyptian Christian killed on train in random police shooting incident Jan. 13 Protesters clash with Egyptian police after fatal train shooting of Copts Jan. 18 Egyptian Court convicts and sentences to death a Muslim man for killing six Copts and a Muslim guard last year. Jan. 19 Suicide attempts in Cairo emulate death in Tunisia as men torch themselves. Religious Coptic celebration cancelled by Pope Shenouda over security fears. Jan 20 The government is considering discounts on basic commodities for workers in an attempt to fend off potential labor protests. Government is currently engaged in earnest discussions with the Egyptian Trade Union Federation to establish class cooperatives that offer basic commodities for laborers at wholesale prices. Meanwhile, the Syndicate of Commercial Professions has decided to hold a meeting with representatives of staff at Omar Effendi retail chain Sunday to preempt possible strikes by workers who are threatening a sit-in if the company does not disburse January salaries. Jan 22 Dozens of protesters in the Gharbiya governorate call for the abolition of Emergency Law, the establishment of a minimum wage and the improvement of social conditions. -

Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods F

Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods F. Desmarais (Ed.) Desmarais F. The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage Cultural objects disappear every day, whether stolen from a museum or removed from an archaeological site, to embark on the well-beaten track of illicit antiquities. A track we have yet to map clearly. The need to understand that journey, to establish the routes, to identify the culprits, and to ultimately locate these sought-after objects, gave rise to the launch of the first International Observatory on Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods by the International Council of Museums (ICOM). This transdisciplinary publication concludes the initial phase of the Observatory project, by providing articles signed by researchers and academics, museum and heritage professionals, archaeologists, legal advisors, curators, and journalists. It includes case studies on looting in specific countries, with the primary aim of eliciting the nature of the antiquities trade, the sources of the traffic, and solutions at hand. Countering Illicit Traffic in in Cultural Goods Illicit Traffic Countering With the financial support of the Prevention and Fight against Crime Programme, European Commission Directorate-General Home Affairs Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage Edited by France Desmarais This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible -

Company Profile 3 Morks Hana St

PRECISION CONSULTING ENGINEERING CREATING YOUR DREAM PRECISELY CONTACT : +20 233382124 +20 1021096980 WWW.PCE-CONSULTANTS.COM COMPANY PROFILE 3 MORKS HANA ST. OFF NAWAL ST., DOKKI, GIZA, EGYPT. CONTACT : 01020470457 - 0233382124 WWW.PCE-CONSULTANTS.COM 3 MORKS HANA ST. OFF NAWAL ST., DOKKI, GIZA, EGYPT. ABOUT US TABLE OF ORGANIZATION CHART CONTENT SERVICES OUR EXPERTISE PROJECTS OUR CLIENTS ABOUT US WHO WE ARE PURPOSE PCE PRECISION CONSULTING ENGINEERING is Professional company for consultancy Our purpose to create, enhance and sustain the world's built natural and social environments. engineering. Projects covering all major disciplines of design and construction supervision. CORE VALUES PCE has successfully accomplished a long list of projects, in Egypt, Africa and the Middle e, civil Our core values recognize that our business success is founded upon our commitment to engineering, electromechanical engineering, infrastructure engineering, tunneling, certain principles. transportation facilities and utilities. INTEGRITY We succeed by doing things the right way, with respect to ethics, laws, quality standards and each other. pre-feasibility and feasibility studies, properties and sites appraisal, selection of new sites CLIENTS for projects, design and detailed engineering of projects, construction management and We succeed by making our clients successful. We embrace our client's challenges and procurement services, construction supervision and inspection services, quality control. opportunities and work for their success VISION EXPERIENCE We earn and advance our reputation by delivering superior value on every project that we undertake. SAFETY portfolio from the entire region. MISSION important measure of success. GROWTH assignments throughout the whole project life-cycle. We are dedicated to deliver Client's principles. -

World Bank Document

PROCUREMENT PLAN (Textual Part) Project information: Egypt Transforming Egypt's Healthcare System Project P167000 Project Implementation agency: Ministry of Health and Population Public Disclosure Authorized Date of the Procurement Plan: October 23, 2018 Period covered by this Procurement Plan: 18 months Preamble In accordance with paragraph 5.9 of the “World Bank Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers” (July 2016) (“Procurement Regulations”) the Bank’s Systematic Tracking and Exchanges in Procurement (STEP) system will be used to prepare, clear and update Procurement Plans and conduct all procurement transactions for the Project. This textual part along with the Procurement Plan tables in STEP constitute the Procurement Plan Public Disclosure Authorized for the Project. The following conditions apply to all procurement activities in the Procurement Plan. The other elements of the Procurement Plan as required under paragraph 4.4 of the Procurement Regulations are set forth in STEP. The Bank’s Standard Procurement Documents: shall be used for all contracts subject to international competitive procurement and those contracts as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP. National Procurement Arrangements: In accordance with paragraph 5.3 of the Procurement Regulations, when approaching the national market (as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP), the country’s own procurement procedures may be used. Public Disclosure Authorized Leased Assets: “Not Applicable” Procurement of Second Hand Goods: “Not Applicable” Domestic -

Internal Ex-Post Evaluation for Technical Cooperation Project The

Internal Ex-Post Evaluation for Technical Cooperation Project conducted by Egypt Office: January, 2020 Country Name The Project for Improvement of Management Capacity of Operation and Arab Republic of Egypt Maintenance for Water Supply Facilities in Nile Delta Area I. Project Outline In 2004, the Egyptian Government established the Holding Company for Water and Wastewater (HCWW) and designated water-supply entities into public corporations. Since the managerial responsibility for operation and maintenance (O&M) of water supply facilities was transferred to public corporations, each company urged to improve operational efficiency and reduce Non-Revenue Water (NRW), which is potable water that cannot be billed, for example, due to leakage and illegal taps. JICA carried out a technical cooperation project, “the Project for Background Improvement of Management Capacity of Operation and Maintenance for SHAPWASCO (Sharkiya Potable Water and Sanitation Company)” between 2006 and 2009, which confirmed the effectiveness of utilizing Standard Operation Procedures (SOPs) and implementing NRW reduction activities to improve operational efficiency. HCWW formulated a plan to transfer successful practices and lessons learned from the previous technical cooperation project to Nile Delta Area for improving management capacity. Through strengthening human resource development in Sharkiya, Gharbia and Minufia Governorates, developing and utilizing SOPs at the model facilities in Gharbia and Minufia Governorates, transferring institutional skills and experiences of SHAPWASCO for NRW reduction to NRW teams in Gharbia and Minufia Governorates, and improving water distribution management (WDM) capacity in Sharkiya Governorate as an advanced model, the project aimed at improving management capacity of water supply facilities at the model areas/facilities in the above Objectives of the three Governorates, thereby improving management capacity of water supply facilities in these Governorates as a Project whole. -

The Quesna Mastaba in the Context of the Early Dynastic-Old Kingdom Mortuary Landscape in Lower Egypt

Edinburgh Research Explorer A new funerary monument dating to the reign of Khaba Citation for published version: Rowland, J & Tassie, GJ 2018, A new funerary monument dating to the reign of Khaba: The Quesna mastaba in the context of the Early Dynastic-Old Kingdom mortuary landscape in Lower Egypt. in M Bárta , F Coppens & J Krejí (eds), Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015: Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 22-26, 2015). Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague, pp. 369-389. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015 Publisher Rights Statement: This is the final published version of the following chapter: Rowland, Joanne; Tassie, G. J. / "A new funerary monument dating to the reign of Khaba : The Quesna mastaba in the context of the Early Dynastic-Old Kingdom mortuary landscape in Lower Egypt" in 'Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015: Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 22-26, 2015)', ed. / Miroslav Bárta ; Filip Coppens; Jaromir Krejí . Prague : Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2018. p. 369-389. For more information please visit: http://cegu.ff.cuni.cz/?req=doc:konference&lang=en General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. -

A New Addition to the Embalmed Fauna of Ancient Egypt

Edinburgh Research Explorer A new addition to the embalmed fauna of ancient Egypt Citation for published version: Woodman , N, Ikram, S & Rowland, J 2021, 'A new addition to the embalmed fauna of ancient Egypt: Güldenstaedt’s White-toothed Shrew, Crocidura gueldenstaedtii (Pallas, 1811) (Mammalia: Eulipotyphla: Soricidae)', PLoS ONE, vol. 16, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249377 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1371/journal.pone.0249377 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: PLoS ONE General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE A new addition to the embalmed fauna of ancient Egypt: GuÈldenstaedt's White-toothed Shrew, Crocidura gueldenstaedtii (Pallas, 1811) (Mammalia: Eulipotyphla: Soricidae) 1,2 3,4 5 Neal WoodmanID *, Salima Ikram , Joanne Rowland 1 U.S. -

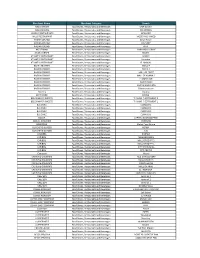

Merchant Name Merchant Category Branch

Merchant Name Merchant Category Branch ABOU SHAKRA Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages KASR EL EINY ABOU SHAKRA Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages HELIOPOLES ANDREA RESTAURANTS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages NEW GIZA ANJUS RESTAURANT Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages YASSER MOHAMED AROMA LOUNGE Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages Down Town AROMA LOUNGE Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages DELIVERY AROMA LOUNGE Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages ALEX ARZ LEBNAN Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages CONCORD LOUNGE ASIAN CORNER Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages MAADI ATLANTIS RESTAURANT Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages MAADI ATLANTIS RESTAURANT Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages Sheraton ATLANTIS RESTAURANT Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages EL MANIAL BAGEL BROTHER Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages WASALY BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages ZAYED 2 BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages MALL OF EGYPT BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages MALL OF ARABIA 2 BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages ELMARGHANI BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages DANDY MALL BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages AMERICANA PLAZA BASKIN ROBBINS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages El Mohandessen Beanery Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages Battaw BEET WARD Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages KORBA BELGIUM FOR SWEETS Food Stores, Restaurants and Beverages THOMAS 5 SETTLMENT 2 BELGIUM FOR SWEETS Food Stores, Restaurants