Story of Lord Clive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9532/carnatic-wars-second-carnatic-war-modern-indian-history-notes-upsc-59532.webp)

Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC]

UPSC Civil Services Examination UPSC Notes [GS-I] Topic: Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC] NCERT notes on important topics for the UPSC Civil Services Exam. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like Bank PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on. This article talks about The First Second War. Facts about the Second Carnatic War Fought between: Different claimants to the posts of the Nizam of Hyderabad, and the Nawab of the Carnatic; each claimant being supported either by the British or the French. People involved: Muhammad Ali and Chanda Sahib (for the Nawabship of the Carnatic or Arcot); Muzaffar Jung and Nasir Jung (for the post of the Nizam of Hyderabad). When: 1749 – 1754 Where: Carnatic (Southern India) Result: Muzaffar Jung became Hyderabad’s Nizam. Muhammad Ali became the Nawab of the Carnatic. Course of the Second Carnatic War The first Carnatic War demonstrated the power of the well-trained European army vis-à-vis the less than efficient armies of the Indian princes. The French Governor-General Dupleix wanted to take advantage of this, and assert influence and authority over the Indian kingdoms, so as to make way for a French Empire in India. So, he was looking to interfere in the internal power struggles among Indian chiefs. Even though England and France were officially at peace with each other as there was no fighting in Europe, the political climate in Southern Indian at that time led their companies to fight in the subcontinent. The Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah I died in 1748 starting a power struggle between his grandson (through his daughter) Muzaffar Jung, and his son Nasir Jung. -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

Volume9 Issue11(6)

Volume 9, Issue 11(6), November 2020 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Associate Professor, Institute of Education Mettu University, Metu, Ethiopia EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S. Mahendra Dev Prof. Igor Kondrashin Vice Chancellor The Member of The Russian Philosophical Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Society Research, Mumbai The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Prof.Y.C. Simhadri Vice Chancellor, Patna University Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Former Director Rector Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Studies, New Delhi & Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Formerly Vice Chancellor of Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Nagarjuna University, Patna University Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Andhra University Visakhapatnam Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Prof.R.Siva Prasadh Vizianagaram IASE Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Asst. Professor Dr.V.Venkateswarlu Dept. of Zoology Assistant Professor Sri.Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Dept. of Sociology & Social Work Delhi Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur I Ketut Donder Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Anthropology Indonesia Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. Roger Wiemers Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Professor of Education Department of Political Economy Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Dr.Kattagani Ravinder Austria Lecturer in Political Science Govt. Degree College Prof. -

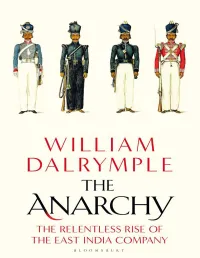

The Anarchy by the Same Author

THE ANARCHY BY THE SAME AUTHOR In Xanadu: A Quest City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857 Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (with Yuthika Sharma) The Writer’s Eye The Historian’s Eye Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (with Anita Anand) Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company 1770–1857 Contents Maps Dramatis Personae Introduction 1. 1599 2. An Offer He Could Not Refuse 3. Sweeping With the Broom of Plunder 4. A Prince of Little Capacity 5. Bloodshed and Confusion 6. Racked by Famine 7. The Desolation of Delhi 8. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings 9. The Corpse of India Epilogue Glossary Notes Bibliography Image Credits Index A Note on the Author Plates Section A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people. Leo Tolstoy, letter to a Hindu, 14 December 1908 Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like. Edward, First Baron Thurlow (1731–1806), the Lord Chancellor during the impeachment of Warren Hastings Maps Dramatis Personae 1. THE BRITISH Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive 1725–74 East India Company accountant who rose through his remarkable military talents to be Governor of Bengal. -

![Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1478/arcot-captured-by-robert-clive-august-31-1751-2051478.webp)

Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751]

Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751] What happened? On 31 August 1751, the English East India Company’s forces led by Robert Clive captured Arcot, the capital of the Nawab of Carnatic (Arcot), Chanda Sahib. This event changed the landscape of British and French colonialism in the subcontinent. This siege was part of the Second Carnatic War. This is an important part of modern Indian history. Siege of Arcot • After the death of the Nawab of Carnatic, Anwaruddin Khan in 1749, Chanda Sahib had become the Nawab of Carnatic with the support of the French. The English had supported another claimant to the post of the Nawab of Carnatic, Muhammad Ali (son of Anwaruddin Khan). • Trichinopoly or Trichy was in the hands of the French and Chanda Sahib, but the Fort of Trichinopoly was held by Muhammad Ali. Chanda Sahib wanted to eliminate Muhammad Ali and consolidate his position as the Carnatic’s Nawab. So, he led a force to besiege the Fort of Trichinopoly. • Even though the British supported Muhammad Ali, their response was weak and the British authorities were bracing themselves to give up Trichy to the French. • Robert Clive, however, had a different plan which he proposed to the Madras Governor, Thomas Saunders. • Clive masterminded a plan to attack Arcot, the capital of Chanda Sahib. This was a divisionary tactic to force Chanda Sahib to lift the siege at Trichy. • Thus, 200 British soldiers along with 300 sepoys and 8 European officers (four of whom were civilians employed with the Company specifically called for this expedition), marched towards Arcot on 26 th August. -

With Clive in India by G. A. Henty

With Clive in India WITH CLIVE IN INDIA: Or, The Beginnings of an Empire By G. A. Henty Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) CONTENTS Preface. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 CHAPTER 1: Leaving Home. .. .. .. .. .. 2 CHAPTER 2: The Young Writer. .. .. .. .. 11 CHAPTER 3: A Brush With Privateers. .. .. .. .. 21 CHAPTER 4: The Pirates Of The Pacific. .. .. .. 30 CHAPTER 5: Madras. .. .. .. .. .. .. 38 CHAPTER 6: The Arrival Of Clive. .. .. .. .. 47 CHAPTER 7: The Siege Of Arcot. .. .. .. .. 56 CHAPTER 8: The Grand Assault. .. .. .. .. 66 CHAPTER 9: The Battle Of Kavaripak. .. .. .. .. 74 CHAPTER 10: The Fall Of Seringam. .. .. .. .. 83 CHAPTER 11: An Important Mission. .. .. .. .. 92 CHAPTER 12: A Murderous Attempt. .. .. .. .. 102 CHAPTER 13: An Attempt At Murder. .. .. .. .. 111 CHAPTER 14: The Siege Of Ambur. .. .. .. .. 121 CHAPTER 15: The Pirates' Hold. .. .. .. .. .. 130 CHAPTER 16: A Tiger Hunt. .. .. .. .. .. 140 CHAPTER 17: The Capture Of Gheriah. .. .. .. .. 150 CHAPTER 18: The "Black Hole" Of Calcutta. .. .. .. 162 CHAPTER 19: A Daring Escape. .. .. .. .. .. 172 CHAPTER 20: The Rescue Of The White Captive. .. .. 182 CHAPTER 21: The Battle Outside Calcutta. .. .. .. 191 CHAPTER 22: Plassey. .. .. .. .. .. .. 199 CHAPTER 23: Plassey. .. .. .. .. .. .. 208 CHAPTER 24: Mounted Infantry. .. .. .. .. .. 216 CHAPTER 25: Besieged In A Pagoda. .. .. .. .. 225 CHAPTER 26: The Siege Of Madras. .. .. .. .. 233 CHAPTER 27: Masulipatam. .. .. .. .. .. 241 CHAPTER 28: The Defeat Of Lally. .. .. .. .. 250 CHAPTER 29: The Siege Of Pondicherry. .. .. .. 259 CHAPTER 30: Home. .. .. .. .. .. .. 267 Preface. In the following pages I have endeavored to give a vivid picture of the wonderful events of the ten years, which at their commencement saw Madras in the hands of the French--Calcutta at the mercy of the Nabob of Bengal--and English influence apparently at the point of extinction in India--and which ended in the final triumph of the English, both in Bengal and Madras. -

KSEEB Class 10 Social Science Part 1

Government of Karnataka SOCIAL SCIENCE (Revised) Part-I ©KTBSrepublished 10 be TENTHto STANDARD Karnataka Textbook Society (R.) Not 100 Feet Ring Road, Banashankari 3rd Stage, Bengaluru - 85 I PREFACE The Textbook Society, Karnataka has been engaged in producing new textbooks according to the new syllabi which in turn are designed on NCF – 2005 since June 2010. Textbooks are prepared in 12 languages; seven of them serve as the media of instruction. From standard 1 to 4 there is the EVS, mathematics and 5th to 10th there are three core subjects namely mathematics, science and social science. NCF – 2005 has a number of special features and they are: • connecting knowledge to life activities • learning to shift from rote methods • enriching the curriculum beyond textbooks • learning experiences for the construction of knowledge • making examinations flexible and integrating them with classroom experiences • caring concerns within the democratic policy of the country • making education relevant to the present and future needs. • softening the subject boundaries- integrated knowledge and the joy of learning. • the child is the constructor of knowledge The new books are produced based on three fundamental approaches namely. Constructive approach, Spiral Approach and Integrated approach The learner is encouraged to think, engage in activities, master skills and competencies. The materials presented in these books are integrated with values. The new books are not examination oriented in their nature. On the other hand they help the learner in the all round development of his/her personality, thus help him/her become a healthy member of a healthy society and a productive citizen of this great country, India. -

British India

British India David Cody, Associate Professor of English, Hartwick College The British presence in India began in Elizabeth's times with a few trading centers at Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta. In the eighteenth century, the French decided to challenge the pre-eminence of the British East India Company, and incited some of the states of the Mogul Empire to attack the British. Robert Clive decisively defeated the French at the Siege of Arcot (1751), for control of the Ganges delta. The French continued to contest Britsh control, however, creating problems for Warren Hastings, the Governor General of the East India Company's holdings between 1772 and 1785. He was impeached (unjustly, it now seems) for high crimes and misdemeanors in 1794 but was acquitted. Lord Cornwallisfresh from Yorktown, Virginia, and Lord Wellesley (the Duke of Duke of Wellington's elder brother) consolidated British power and brought a measure of peace to the warring Indian states during theirn Governor-Generalships (1786-93 and 1794-1805, respectively). During the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, India was the place where many of the second sons of titled families (who would not inherit the family estate, and consequently had to choose between the Church and the Army) went as Army officers to make their fortunes. The British were more or less welcome (indeed, there were a number of highly connected Anglo-Indian families) until the Mutiny of 1857-58. Its immediate cause was the cartridge for the new Enfield rifle, which had to be bitten before it was loaded: Rumors spread that the cartridge was greased with cow-fat and pig-lard; and since the cow is sacred to the Hindus and the pig considered unclean by the Moslems, both religious groups were offended. -

Arcot Hall , the History and the Golf Club

This is a brief history of Arcot itself, and where the name comes from. Arcot is a locality and part of Vellore City in the state of Tamil Nadu, India. Which is in the south east of the country. Located on the eastern end of the Vellore City on the southern banks of Palar River. The city straddles a highly strategic trade route between Chennai and Bangalore, between the Mysore Ghat The name is believed to have derived from the Tamil words, AARU (river) +KAADU (forest). However ARKKATU means ‘a forest. The town’s strategic location has led to it being repeatedly contested and prompted the construction of a formidable fortress by Muslim Nawab of Karnataka, who made it his capital, and in 1712 the English captured the town during the conflict between the United Kingdom and France for the control of South India. The people who lived in the Arcot region, especially in and near the temple belonged to a clan called the Arcot’s. The Battle of Arcot took place on November 14th 1751 between forces of the English East India Company, led by Robert Clive, and the forces of the French East India Company. Clive’s victory at the battle of Arcot marked a sea change in the British experience in India. France lost its colonial empire ambitions and it made Clive a very wealthy and illustrious man. Incidentally 4th Regiment Royal Artillery, which were originally Known as the 4th Royal Horse Artillery, are comprised of six batteries. Of which, one of which is called 6/36 Arcot 1751 Battery. -

![Robert Clive [Modern Indian History Notes for UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7022/robert-clive-modern-indian-history-notes-for-upsc-7247022.webp)

Robert Clive [Modern Indian History Notes for UPSC]

UPSC Civil Services Examination UPSC Notes [GS-I] Topic: NCERT Notes: Robert Clive [Modern Indian History Notes for UPSC] NCERT notes on important topics for the IAS aspirants. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like banking PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on. This article talks about Robert Clive. Robert Clive was largely responsible for the East India Company getting control of Bengal thus leading to the whole of India later on. So, it can be said that Clive laid the foundations of the British Raj in India. Background Born in 1725 in England. Arrived in Fort St. George (Madras) in 1744 to work for the East India Company as a ‘factor’ or company agent. He enlisted in the company army where he was able to prove his ability. He earned great fame and praise for his role in the Siege of Arcot which saw a British victory against the larger forces of Chanda Sahib, the Nawab of the Carnatic and French East India Company’s forces. Also known as “Clive of India”. Clive in India Clive’s initial stay in India lasted from 1744 to 1753. He was called back to India in 1755 to ensure British supremacy in the subcontinent against the French. He became the deputy governor of Fort St. David at Cuddalore. In 1757, Clive along with Admiral Watson was able to recapture Calcutta from the Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah. In the Battle of Plassey, the Nawab was defeated by the British despite having a larger force. Clive ensured an English victory by bribing the Nawab’s army commander Mir Jaffar, who was installed as Bengal’s Nawab after the battle. -

University of Bristol

University of Bristol Department of Historical Studies Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Alexander Windsor-Clive Clive of India; A Reception History 1767-1940 The Department of Historical Studies at the University of Bristol is com- mitted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. Our undergraduates are part of that en- deavour. Since 2009, the Department has published the best of the annual disserta- tions produced by our final year undergraduates in recognition of the ex- cellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. University of Bristol Undergraduate History Dissertation 2015 Clive of India: A Reception History 1767-1940 Candidate Number: 58992 Word Count: 9,358 1 Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: 1767-1800 7 Chapter 2: 1800-1880 16 Chapter 3: 1880-1940 22 Conclusion 27 Bibliography 29 2 Introduction During the eighteenth century, Robert Clive (1725-1774), was one of the most important and controversial figures in the formation of British India. -

Lives of the Lindsays, Or, a Memoir of the House of Crawford and Balcarres

ilmllllMM N'E ; S", 1 >x . 2 , National Library of Scotland II II III 1 1 III B000031768* J? * -P LIVES THE LINDSAYS. VOL. IV. r \ 1 9 6 9 ; Oriental JWtecellantetf COMPRISING ANECDOTES OF AN INDIAN LIFE, BY THE HON. ROBERT LINDSAY; NARRATIVES OF THE BATTLE OF CONJEVERAM, &c, BY THE HON. JAMES AND JOHN LINDSAY; JOURNAL OF AN IMPRISONMENT IN SERINGAPATAM, BY THE HON. JOHN LINDSAY; AN ADVENTURE IN CHINA, BY THE HON. HUGH LINDSAY. WIGAN: PRINTED BY C. S. SIMMS. 1840. CONTENTS. Anecdotes of an Indian Life. By the Hon. Robert Lindsay. page 1 Two Narratives of the proceedings of the British army under General Sir Hector Munro and Colonel Baillie, and of the battle of Con- jeveram, 10th Sept., 1780, in which the division under Colonel Baillie was either cut to pieces or taken prisoners. By the Hon. James and John Lindsay, 73d Highlanders 117 Journal of an Imprisonment in Seringapatam, during the years 1781, 1782, 1783, and part of 1780 and 1784. By the Hon. John Lindsay 1 69 An Adventure in China. By the Hon. Hugh Lindsay 281 General Index to the four volumes 297 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/livesoflindsaysv400craw ANECDOTES OF AN INDIAN LIFE, THE HON. ROBERT LINDSAY. : ANECDOTES OF AN INDIAN LIFE, &c. INTRODUCTION. "Men leave the pictures of their frail and transitory persons to their families ; some lineaments of their mind were a better legacy, and would make them more known to posterity."—The truth of my father's observation is obvious, and, were each individual to keep a diary of the occurrences that happen to him during his journey through life, anecdotes would be found, to fill an inter- esting volume.