Chapter 2: the Walajahs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9532/carnatic-wars-second-carnatic-war-modern-indian-history-notes-upsc-59532.webp)

Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC]

UPSC Civil Services Examination UPSC Notes [GS-I] Topic: Carnatic Wars - Second Carnatic War [Modern Indian History Notes UPSC] NCERT notes on important topics for the UPSC Civil Services Exam. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like Bank PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on. This article talks about The First Second War. Facts about the Second Carnatic War Fought between: Different claimants to the posts of the Nizam of Hyderabad, and the Nawab of the Carnatic; each claimant being supported either by the British or the French. People involved: Muhammad Ali and Chanda Sahib (for the Nawabship of the Carnatic or Arcot); Muzaffar Jung and Nasir Jung (for the post of the Nizam of Hyderabad). When: 1749 – 1754 Where: Carnatic (Southern India) Result: Muzaffar Jung became Hyderabad’s Nizam. Muhammad Ali became the Nawab of the Carnatic. Course of the Second Carnatic War The first Carnatic War demonstrated the power of the well-trained European army vis-à-vis the less than efficient armies of the Indian princes. The French Governor-General Dupleix wanted to take advantage of this, and assert influence and authority over the Indian kingdoms, so as to make way for a French Empire in India. So, he was looking to interfere in the internal power struggles among Indian chiefs. Even though England and France were officially at peace with each other as there was no fighting in Europe, the political climate in Southern Indian at that time led their companies to fight in the subcontinent. The Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah I died in 1748 starting a power struggle between his grandson (through his daughter) Muzaffar Jung, and his son Nasir Jung. -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

CC-12:HISTORY of INDIA(1750S-1857) II.EXPANSION and CONSOLIDATION of COLONIAL POWER

CC-12:HISTORY OF INDIA(1750s-1857) II.EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION OF COLONIAL POWER: (A) MERCANTILISM,FOREIGN TRADE AND EARLY FORMS OF EXTRACTION FROM BENGAL The coming of the Europeans to the Indian subcontinent was an event of great significance as it ultimately led to revolutionary changes in its destiny in the future. Europe’s interest in India goes back to the ancient times when lucrative trade was carried on between India and Europe. India was rich in terms of spices, textile and other oriental products which had huge demand in the large consumer markets in the west. Since the ancient time till the medieval period, spices formed an important part of European trade with India. Pepper, ginger, chillies, cinnamon and cloves were carried to Europe where they fetched high prices. Indian silk, fine Muslin and Indian cotton too were much in demand among rich European families. Pearls and other precious stone also found high demand among the European elites. Trade was conducted both by sea and by land. While the sea routes opened from the ports of the western coast of India and went westward through the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Alexandria and Constantinople, Indian trade goods found their way across the Mediterranean to the commercials hubs of Venice and Genoa, from where they were then dispersed throughout the main cities of Europe. The old trading routes between the east and the west came under Turkish control after the Ottoman conquest of Asia Minor and the capture of Constantinople in1453.The merchants of Venice and Genoa monopolised the trade between Europe and Asia and refused to let the new nation states of Western Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, have any share in the trade through these old routes. -

Story of Lord Clive

Conditions and Terms of Use Copyright © Heritage History 2010 TO ST. CLAIR CUNNINGHAM Some rights reserved This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an Dear St. Clair, organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. The tell me that you are going to be a soldier. The books which Heritage History republishes are in the I do not know upon which branch of the Service you public domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. have set your heart, but, whichever it may be, you cannot They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without go wrong if you take for your model that great fighter, Lord paying a royalty to the author. Clive, of some of whose deeds I have tried to tell you. The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are the property of Heritage History and are subject to certain Yours always, restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity of the work, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to JOHN LANG. assure that compromised versions of the work are not widely disseminated. In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this text, a copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date are included at the foot of every page of text. We require all electronic TABLE OF CONTENTS and printed versions of this text include these markings and that users adhere to the following restrictions. -

Volume9 Issue11(6)

Volume 9, Issue 11(6), November 2020 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Associate Professor, Institute of Education Mettu University, Metu, Ethiopia EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S. Mahendra Dev Prof. Igor Kondrashin Vice Chancellor The Member of The Russian Philosophical Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Society Research, Mumbai The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Prof.Y.C. Simhadri Vice Chancellor, Patna University Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Former Director Rector Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Studies, New Delhi & Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Formerly Vice Chancellor of Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Nagarjuna University, Patna University Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Andhra University Visakhapatnam Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Prof.R.Siva Prasadh Vizianagaram IASE Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Asst. Professor Dr.V.Venkateswarlu Dept. of Zoology Assistant Professor Sri.Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Dept. of Sociology & Social Work Delhi Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur I Ketut Donder Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Anthropology Indonesia Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. Roger Wiemers Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Professor of Education Department of Political Economy Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Dr.Kattagani Ravinder Austria Lecturer in Political Science Govt. Degree College Prof. -

S. Nalina.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts BRITISH IN THE WALLAJAH - MYSORE STRUGGLE FOR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI Abstract:- Mohammad Ali, the Nawab of Arcot had sought the alliance of Mysore against Chanda Sahib on condition that he would cede Tiruchirappalli to Mysore if he succeeded in the conflict. But Mohammed Ali flagrantly violated his solemn assurance and refused the cession of Tiruchirappalli to Mysore. However, Srirangam was left to be occupied by the Mysorean. In 1752, there ensued a struggle between the two groups of native power over the region of Tiruchirappalli. The British involved in the struggle in favour of Mohammed Ali to drive away the Mysoreans form the soil of the Tiruchirappalli. Mohammed Ali at first told the Mysore Rajah that he would consider the Rajah's demand after two months. When the Mysore King, Nanja Rajah pressed, Mohammed Ali said that the territory belonged to the Mughals and he could not alienate the Mughal's property. He was supported by the British and the native powers of Pudukkottai and Tanjore. On the other hand, the Mysore king got the assistance of Murari Rao, the Maratha Chief, the French and the Maravars. Eventually in the Wallajah - Mysore conflict over Tiruchirappalli region, the cause of the Nawab’s was won with the military aid and assistance of the British. However the growing influence of the British in Tiruchirappalli region eroded the power of the Nawab Wallajah there. The introduction of assignment and assumption brought the Tiruchirappalli region under S. Nalina the direct control of the British. Ph.D Research Scholar Keywords: in History , H.H.Rajah’s Government British , Wallajah, Nawab, Carnatic, Tiruchirappalli, College (Autonomous) Pudukkottai Mysore, Ariyalur, Udaiyarpalayam, Tanjore, Hyder Ali. -

I: COMING of the EUROPEANS Dr. A. Ravisankar, Ph.D., Portuguese, Dutch, Danes, British, &French Portuguese: (Headquarters Goa)

I: COMING OF THE EUROPEANS Dr. A. Ravisankar, Ph.D., Portuguese, Dutch, Danes, British, &French Portuguese: (Headquarters Goa) • In 21st May,1498- Vasco da Cama landed in Calicut, with the patronage of King Emmanuel (Portugal)- cordially received by King Zamorin- opposed by the Arabs. • 1510 Goa was captured by Albuquerque- he was died and buried at Goa in 1515. Important Portuguese to visit India 1. Vasco da Cama-1498 2. Alvarez Cabral- 1500 3. Lopo Soares- 1503 4. Francisco de Almedia 1505 5. Albuquerque 1509 6. Nuno da Cunha- 1529-1538 7. Joa de Castro-1545- 1548 Important Portuguese Writers 1. Duarle Barbosa 2. Gasper Correa 3. Diago do Couto 4. Bros de Albuquerque 5. Dom Joao de Castro 6. Garcia de Orta. Causes for the failure • Weak successors • Corrupt administration • Naval Supremacy of British • Rise of other European trading powers • Discovery of Brazil- less attention towards Indian Territory. Important Works 1. Cultivation of Tobacco & Potato 2. 1st Printing Press (1556) 3. 1st Scientific work on Indian Medicinal plants. The Dutch (Headquarters Pulicat & Nagapatnam) • They all from Netherland • 1stPermanent Factory at Maulipatnam (1605) Dutch Factories in the Coromandel Coast: 1. Masulipatnam 2. Pettapoli 3. Devenampatnam 4. Tirupapuliyar 5. Pulicat 6. Nagapatnam 7. Porto Novo 8. Sadraspatanam 9. Golcunda 10. Nagal Wanche 11. Palakollu 12. Drakshram 13. Bimplipatnam Dutch Factories in Bengal 1. Pipli 2. Chinsura 3. Qasim Bazar 4. Patna Reason for Decline • Rise of English power • The authority was highly centralized • Officers of the Company became corrupt • Majority of the settlement was given to English. The French (Head Quarters Pondichery) • 1st French factory was established at Surat by Francois Caron • Pondichery was obtained from Sher Khan Lodi (Governor of Valikondapuram) by Francois Martin. -

Unit 2- from Trade to Territory Class : VIII Subject : Social Science I

Unit 2- From Trade to Territory Class : VIII Subject : Social Science I. Choose the correct answer: 1. The ruler of Bengal in 1757 was___________. a) Shuja-ud-daulah b) Siraj-ud-daulah c) Mir Qasim d) Tipu Sultan 2. The Battle of Plassey was fought in__________. a) 1757 b) 1764 c) 1765 d) 1775 3. Which among the following treaty was signed after Battle of Buxar? a) Treaty of Allahabad b) Treaty of Carnatic c) Treaty of Alinagar d) Treaty of Paris 4. The Treaty of Pondichery brought the __________ Carnatic war to an end. a) First b) Second c) Third d) None 5. When did Hyder Ali crown on the throne of Mysore? a) 1756 b) 1761 c) 1763 d) 1764 6. Treaty of Mangalore was signed between ____________ a) The French and Tipu Sultan b) Hyder Ali and Zamorin of Calicut c) The British and Tipu Sultan d) Tipu Sultan and Marathas 7. Who was the British Governor General during Third Anglo-Mysore War? a) Robert Clive b) Warren Hastings c) Lord Cornwallis d) Lord Wellesley 8. Who signed the Treaty of Bassein with the British? a) Bajirao II b) Daulat Rao Scindia c) Sambhaji Bhonsle d) Sayyaji Rao Gaekwad 9. Who was the last Peshwa of Maratha empire? a) Balaji Vishwanath b) Baji Rao II c) Balaji Baji Rao d) BajiRao 10. Who was the first Indian state to join the subsidiary Alliance? a) Awadh b) Hyderabad c) Udaipur d) Gwalior II. Fill in the blanks: 1. The Treaty of Alinagar was signed in 1756 . 2. The commander in Chief of Sirajuddaulah Mir Jafer 3. -

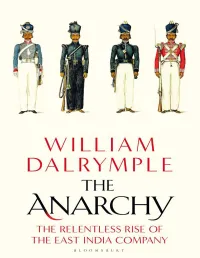

The Anarchy by the Same Author

THE ANARCHY BY THE SAME AUTHOR In Xanadu: A Quest City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857 Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (with Yuthika Sharma) The Writer’s Eye The Historian’s Eye Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (with Anita Anand) Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company 1770–1857 Contents Maps Dramatis Personae Introduction 1. 1599 2. An Offer He Could Not Refuse 3. Sweeping With the Broom of Plunder 4. A Prince of Little Capacity 5. Bloodshed and Confusion 6. Racked by Famine 7. The Desolation of Delhi 8. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings 9. The Corpse of India Epilogue Glossary Notes Bibliography Image Credits Index A Note on the Author Plates Section A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people. Leo Tolstoy, letter to a Hindu, 14 December 1908 Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like. Edward, First Baron Thurlow (1731–1806), the Lord Chancellor during the impeachment of Warren Hastings Maps Dramatis Personae 1. THE BRITISH Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive 1725–74 East India Company accountant who rose through his remarkable military talents to be Governor of Bengal. -

![Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1478/arcot-captured-by-robert-clive-august-31-1751-2051478.webp)

Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751]

Arcot Captured by Robert Clive -[August 31, 1751] What happened? On 31 August 1751, the English East India Company’s forces led by Robert Clive captured Arcot, the capital of the Nawab of Carnatic (Arcot), Chanda Sahib. This event changed the landscape of British and French colonialism in the subcontinent. This siege was part of the Second Carnatic War. This is an important part of modern Indian history. Siege of Arcot • After the death of the Nawab of Carnatic, Anwaruddin Khan in 1749, Chanda Sahib had become the Nawab of Carnatic with the support of the French. The English had supported another claimant to the post of the Nawab of Carnatic, Muhammad Ali (son of Anwaruddin Khan). • Trichinopoly or Trichy was in the hands of the French and Chanda Sahib, but the Fort of Trichinopoly was held by Muhammad Ali. Chanda Sahib wanted to eliminate Muhammad Ali and consolidate his position as the Carnatic’s Nawab. So, he led a force to besiege the Fort of Trichinopoly. • Even though the British supported Muhammad Ali, their response was weak and the British authorities were bracing themselves to give up Trichy to the French. • Robert Clive, however, had a different plan which he proposed to the Madras Governor, Thomas Saunders. • Clive masterminded a plan to attack Arcot, the capital of Chanda Sahib. This was a divisionary tactic to force Chanda Sahib to lift the siege at Trichy. • Thus, 200 British soldiers along with 300 sepoys and 8 European officers (four of whom were civilians employed with the Company specifically called for this expedition), marched towards Arcot on 26 th August. -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt. -

Conflict and Expansion : South India

CONFLICT AND EXPANSION : SOUTH INDIA Structure , 9.0 ~bjebives' 9.1 lntroduction 9.2 The English and the French in India- Their strengths and Weaknesses 9.3 The First Carnatic War (1 740-48) 9.3.1 The role of the Nawab of Carnatic 9.3.2 Defiance of Dupleix by the French Admiral 9.3.3 Superiority of French in First Carnatic War .9.4 The Second Carnatic War (1 75 1-55) 9.4.1 Success~onRivalry in Carnatic and Hydaabad 9.4.2 Oupleix's Intervention 9.4.3 Entry of the British 9.4.4 Recall of Dupleix . 9.4.5 French Influence Restricted to Hyderabad 9.5 The Third Carnatic War (1758-63) 9.5.1 French Offensives in Carnat~c ' 9.5.2 Problems of the French Army 9.5.3 The Naval Debacle . 9.5.4 Battle of Wand~wash . 9.6 Causes bf French Failure 9.7 The,kfkrmath . 9.8 .Let 11s Sum Up 9.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises -9.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this Unit, you will learn the following points: d the two major foreign trading companies that existed in South lndia in the 18th century i.e. the Engllsh and the .French; their relative strengths, and weaknesses, . , 0 the extent to whicli Indian powers were able to withstand foreign interference in their affairs as well as aggression against them, the nature of the conflict between the English and French companies as it unfolded from 1740 onward, and ' @ the economic, political and military factors which were to determine tlie outcome of this conflict.