Interrogating Virginia Woolf and the British Suffrage Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Between the Lines: Paradigmatic Readings of the Relationship Between Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey Janine Loedolff Th

Love Between The Lines: Paradigmatic Readings of the Relationship between Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey Janine Loedolff Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Dr S.C. Viljoen Co-supervisor: Prof. E.P.H. Hees November 2007 Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: Copyright ©2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements Dr Shaun Viljoen, for teaching me about uncommon lives; My co-supervisor, Prof. Edwin Hees; Mathilda Slabbert, for telling me the story for the first time, and for her inspirational enthusiasm; Roshan Cader, for her encouragement and willingness to debate the finer points of performativity with me; Sarah Duff, for continuously demanding clarity, and for allowing me to stay at Goodenough College; Dawid de Villers, for translations; Evelyn Wiehahn, Neil Micklewood, Daniela Marsicano, Simon Pequeno and Alexia Cox for their many years of love and friendship; Larry Ferguson, who always tells me I have something to say; My father, Johan, and his extended family, for their continual love and support and providing me with a comforting refuge; My family in England – Chicky for taking me to Charleston, and Melanie for making her home mine while I was researching at the British Library; and Joe Loedolff, for eternal optimism, words of wisdom, and most importantly, his kinship. -

Suffrage and Virginia Woolf 121 Actors

SUFFRAGE AND VIRGINIAWOOLF: ‘THE MASS BEHIND THE SINGLE VOICE’ by sowon s. park Virginia Woolf is now widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom twenty- ¢rst- century feminists think back, but she was ambivalent towards the su¡ragette movement. Feminist readings of the uneasy relation betweenWoolf and the women’s Downloaded from movement have focused on her practical involvement as a short-lived su¡rage campaigner or as a feminist publisher, and have tended to interpret her disapproving references to contemporary feminists as redemptive self-critique. Nevertheless the apparent contradictions remain largely unresolved. By moving away from Woolf in su¡rage to su¡rage in Woolf, this article argues that her work was in fact deeply http://res.oxfordjournals.org/ rooted at the intellectual centre of the su¡rage movement. Through an examination of the ideas expressed in A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas and of two su¡rage characters, Mary Datchet in Night and Day and Rose Pargiter in TheYears,it establishes how Woolf’s feminist ideas were informed by su¡rage politics, and illumi- nates connections and allegiances as well as highlighting her passionate resistance to a certain kind of feminism. at Bodleian Library on October 20, 2012 I ‘No other element in Woolf’s work has created so much confusion and disagree- mentamongherseriousreadersasherrelationtothewomen’smovement’,noted Alex Zwerdling in 1986.1 Nonetheless the women’s movement is an element more often overlooked than addressed in the present critical climate. And Woolf in the twentieth- ¢rst century is widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom feminists think back, be they of liberal, socialist, psychoanalytical, post-structural, radical, or utopian persuasion. -

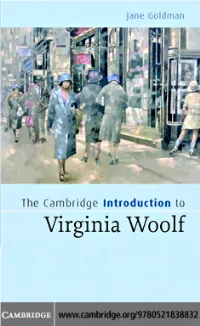

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf for Students of Modern Literature, the Works of Virginia Woolf Are Essential Reading

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf For students of modern literature, the works of Virginia Woolf are essential reading. In her novels, short stories, essays, polemical pamphlets and in her private letters she explored, questioned and refashioned everything about modern life: cinema, sexuality, shopping, education, feminism, politics and war. Her elegant and startlingly original sentences became a model of modernist prose. This is a clear and informative introduction to Woolf’s life, works, and cultural and critical contexts, explaining the importance of the Bloomsbury group in the development of her work. It covers the major works in detail, including To the Lighthouse, Mrs Dalloway, The Waves and the key short stories. As well as providing students with the essential information needed to study Woolf, Jane Goldman suggests further reading to allow students to find their way through the most important critical works. All students of Woolf will find this a useful and illuminating overview of the field. JANE GOLDMAN is Senior Lecturer in English and American Literature at the University of Dundee. Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers Concise, yet packed with essential information Key suggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. S. Eliot Dillon The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre Goldman The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf Holdeman The Cambridge Introduction to W. -

A “Feminine” Heartbeat in Evangelicalism and Fundamentalism

A “Feminine” Heartbeat in Evangelicalism and Fundamentalism DAVID R. ELLIOTT Protestant fundamentalism has often been characterized as militant, rationalistic, paternalistic and even misogynist.1 This was particularly true of Baptist and Presbyterian fundamentalists who were Calvinists. Yet, evangelicalism and fundamentalism also had a feminine, mystical, Arminian expression which encouraged the active ministry of women and which had a profound impact upon the shaping of popular piety through devotional writings and mystical hymnology.2 This paper examines the “feminine” presence in popular fundamentalism and evangelicalism by examining this expression of religion from the standpoint of gender, left brain/right brain differences, and Calvinistic versus Arminian polarities. The human personality is composed of both rational and emotional aspects, both of equal value. The dominance of either aspect reflects the favouring of a particular hemisphere of the brain. Males have traditionally emphasized the linear, rational left side of the brain over the intuitive, emotional right side. Females have tended to utilize the right side of the brain more,3 although some males are more right-brained and some females are more left-brained. Such differences may be genetic, hormonal or sociological. Brain researcher Marilyn Ferguson favours the sociologi- cal explanation and suggests a deliberate reorientation to the right side of the brain as means of transforming society away from confrontation to a state of peace. She sees the feminist movement accomplishing much of this transformation of society by emphasizing the right side of the brain.4 When looking at the two dominant expressions of Protestantism – Historical Papers 1992: Canadian Society of Church History 80 “Feminine” Heartbeat in Evangelicalism and Fundamentalism Calvinism and Methodism, we find what appears to be a left/right brain dichotomy. -

Cheerful Weather for the Wedding Free

FREE CHEERFUL WEATHER FOR THE WEDDING PDF Julia Strachey | 128 pages | 31 Dec 2011 | Persephone Books Ltd | 9781906462079 | English | London, United Kingdom Cheerful Weather for the Wedding (film) - Wikipedia As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six Cheerful Weather for the Wedding to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. Title: Cheerful Weather for the Wedding The last summer, shown in major flashbacks, dashing archaeologist Joseph Luke Treadaway has brilliantly flirted with upper middle-class girl Dolly Thatcham Felicity JonesCheerful Weather for the Wedding her cute naughty kid brother Jimmy Ben Greaves-Neal and even her headless younger sister Annie Eva Traynoryet antagonized their mother, stuck-up widow Mrs. Thatcham Elizabeth McGovern. When bashful Dolly refused to accompany Joseph on a Greek excavation due to his commitment problems, she was afterwards sent on an Albanian holiday, met stuffy diplomat Owen James Norton and got engaged. At the wedding day, Dolly hesitated whether she was giving up on her best chance for happiness, and Joseph turned up, but the party guests and obligations kept getting in the way of actually talking it through. Written by KGF Vissers. Just before I sat down to watch this movie I had painted a floor. Watching that dry would have been more interesting. I continued to watch as an exercise in masochism. Maybe because I find the lead actress very unpleasant. She drank way to much and pretty much continuously. Never did really get who all the other people were, yes, a sister and a mother. Was the vicar the father? An annoying missionary guest. -

BATTERSEA Book Fair List, 2018

BATTERSEA Book Fair List, 2018 . STAND M09 Item 43 BLACKWELL’S RARE BOOKS 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ, UK Tel.: +44 (0)1865 333555 Fax: +44 (0)1865 794143 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @blackwellrare blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks BLACKWELL’S RARE BOOKS 1. Abbott (Mary) [Original artwork:] Sketch Book. early 1940s, sketches in ink and pencil throughout, some use of colour, text of various types (mostly colouring suggestions, some appointments, and a passage of lyrical prose), pp. [190, approx.], 4to, black cloth, various paint spots, webbing showing at front hinge, rear hinge starting, loose gathering at rear, ownership inscription of ‘Mary Lee Abbott, 178 Spring Street’, sound £15,000 An important document, showing the early progress of one of the key figures of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism; various influences, from her immediate surroundings to the European avant-garde, are evident, as are the emergent characteristics of her own style - the energetic use of line, bold ideas about colour, the blending of abstract and figurative. Were the nature of the work not indicative of a stage of development, the presence of little recorded details such as an appointment with Vogue magazine would supply an approximate date - Abbott modelled for the magazine at the beginning of this decade. 2. Achebe (Chinua) Things Fall Apart. Heinemann, 1958, UNCORRECTED PROOF COPY FOR FIRST EDITION, a couple of handling marks and a few faint spots occasionally, a couple of passages marked lightly in pencil to the margin, pp. [viii], -

A Feminist Economist?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Marouzi, Soroush Working Paper Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A feminist economist? CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2021-09 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Marouzi, Soroush (2021) : Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A feminist economist?, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2021-09, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3854782 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234320 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A Feminist Economist? Soroush Marouzi CHOPE Working Paper No. 2021-09 May 2021 FRANK PLUMPTON RAMSEY: A FEMINIST ECONOMIST? BY Soroush Marouzi* Abstract: This paper is an attempt to historicize Frank Plumpton Ramsey’s Apostle talks delivered from 1923 to 1925 within the social and political context of the time. -

'The Mass Behind the Single Voice'

SUFFRAGE AND VIRGINIAWOOLF: ‘THE MASS BEHIND THE SINGLE VOICE’ by sowon s. park Virginia Woolf is now widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom twenty- ¢rst- century feminists think back, but she was ambivalent towards the su¡ragette movement. Feminist readings of the uneasy relation betweenWoolf and the women’s Downloaded from movement have focused on her practical involvement as a short-lived su¡rage campaigner or as a feminist publisher, and have tended to interpret her disapproving references to contemporary feminists as redemptive self-critique. Nevertheless the apparent contradictions remain largely unresolved. By moving away from Woolf in su¡rage to su¡rage in Woolf, this article argues that her work was in fact deeply http://res.oxfordjournals.org/ rooted at the intellectual centre of the su¡rage movement. Through an examination of the ideas expressed in A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas and of two su¡rage characters, Mary Datchet in Night and Day and Rose Pargiter in TheYears,it establishes how Woolf’s feminist ideas were informed by su¡rage politics, and illumi- nates connections and allegiances as well as highlighting her passionate resistance to a certain kind of feminism. at Bodleian Library on October 20, 2012 I ‘No other element in Woolf’s work has created so much confusion and disagree- mentamongherseriousreadersasherrelationtothewomen’smovement’,noted Alex Zwerdling in 1986.1 Nonetheless the women’s movement is an element more often overlooked than addressed in the present critical climate. And Woolf in the twentieth- ¢rst century is widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom feminists think back, be they of liberal, socialist, psychoanalytical, post-structural, radical, or utopian persuasion. -

Hannah Whitall Smith ARC1983 -002 - Finding Aid Hannah Whitall Smith

Asbury Theological Seminary ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange Finding Aids Special Collections 2012 Hannah Whitall Smith ARC1983 -002 - Finding Aid Hannah Whitall Smith Follow this and additional works at: http://place.asburyseminary.edu/findingaids Recommended Citation Smith, Hannah Whitall, "Hannah Whitall Smith ARC1983 -002 - Finding Aid" (2012). Finding Aids. Book 49. http://place.asburyseminary.edu/findingaids/49 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Asbury Theological Seminary Information Services Special Collections Papers of Hannah Whitall Smith ARC1983 -002 Asbury Theological Seminary Information Services Special Collections Papers of Hannah Whitall Smith ARC1983 -002 Introduction The Hannah Whitall Smith Papers (1847-1960) include personal materials that relate to Hannah Whitall Smith’s career as an evangelist, author, feminist, and temperance reformer. The Papers cover especially her adult years, from 1850 until her death in 1911. Her family has added a few pieces to the collection throughout the years following her death. The papers are composed of correspondence sent to Hannah W. Smith; subject files, including a large section of clippings, pamphlets, books, and broadsides about fanaticisms of her day, which she herself collected; literary productions, including her journal (1849-1880); printed materials; and photographic materials. The Special Collections Department of the B.L. Fisher Library received the Hannah Whitall Smith Papers collection, which contains 4.8 cubic feet of manuscript materials, in 1983 from Barbara M. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. EBgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A POETICS OF LITERARY BIOGRAPHY; THE CREATION OF “VIRGINIA WOOLF’ DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Docotor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Julia Irene Keller, B.A., M. -

The Smiths - a Biographical Sketch with Selected Items from the Collection

The Smiths - a Biographical Sketch with Selected Items from the Collection by Melvin E. Dieter Hannah Whitall Smith, her husband Robert Pearsall Smith, and their children have presented a stark anomaly to the many biographers and historians who have tried to tell their story. Because of the radical dichotomies which must be wrestled with in the telling, the story of this remarkable Quaker family often has not been told with balance, depth of understanding, and wholeness. The generations of Smiths who followed Hannah and Robert were completely immersed in a world of intellectual ability and literary talent. This assured that records of these exceptional people would be published and widely read. The philosophical ambience of that milieu, however, was strongly agnostic, contributing to more negative representations of the religious movements with which the Smiths were involved than might have been reported by interpreters with a transcendental view of reality. Mrs. Barbara Strachey Halpern, the Smiths' great-granddaughter, is the first to look at the history from a broader perspective. Mrs. Halpern's interest in a view from "another side" encouraged me to research in the family collection at her home in Oxford last fall. Her generosity also made it possible for Asbury Theological Seminary to purchase the "religious collection" section of the Smith family papers for the B.L. Fisher Library. The anomaly presented by this family's history is created by the two, almost mutually contradictory, historical images which Robert and Hannah seemed to reflect as they played out their public roles in two quite different nineteenth century worlds. -

1 Number 95 Spring/Summer 2019

NUMBERVirginia 95 Woolf Miscellany SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Editor’s Introduction: o o o o Elizabeth Willson Gordon has argued, convincingly, The Common Book Collector that an entire sequence of contradictions animates You can access issues of the the marketing of the Hogarth Press from the first. If Virginia and Leonard Woolf were not book Virginia Woolf Miscellany the original intention behind Hogarth Press books collectors, which is to say that theirs was a online on WordPress at was to create affordable and attractive books for working library and they were not precious about https://virginiawoolfmiscellany. texts that the “commercial publisher could not the condition of their books. George Holleyman, wordpress.com/ or would not publish” (L. Woolf 80), they were the Brighton bookseller who arranged the sale of – TABLE OF CONTENTS – also intelligently marketed, with a “discourse of the Monk’s House Library to Washington State See page 22 exclusivity” that confers “distinction” on their University, described the general condition of the In Memoriam coterie audience (Willson Gordon 109). Even the 9,000 volumes remaining in the Woolfs’ library Cecil James Sidney Woolf famous imperfections of the handprinted Hogarth after Leonard’s death as “poor”: “it was always See page 8-21 Press books “employ casualness as a market essentially a working library and neither Leonard strategy”; therefore, “a printing press of one’s own INTERNATIONAL nor Virginia cared for fine books or collectors’ is both elitist and democratic” (Willson Gordon VIRGINIA WOOLF pieces. No books were kept behind glass and no 113, 112). This “both-and” model also applies to item was specially cared for.