East Wind Over Arabia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

Prometric Combined Site List

Prometric Combined Site List Site Name City State ZipCode Country BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA LAB.1 Buenos Aires ARGENTINA 1006 ARGENTINA YEREVAN, ARMENIA YEREVAN ARMENIA 0019 ARMENIA Parkus Technologies PTY LTD Parramatta New South Wales 2150 Australia SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA Sydney NEW SOUTH WALES 2000 NSW AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 VIC AUSTRALIA PERTH, AUSTRALIA PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6155 WA AUSTRALIA VIENNA, AUSTRIA Vienna AUSTRIA A-1180 AUSTRIA MANAMA, BAHRAIN Manama BAHRAIN 319 BAHRAIN DHAKA, BANGLADESH #8815 DHAKA BANGLADESH 1213 BANGLADESH BRUSSELS, BELGIUM BRUSSELS BELGIUM 1210 BELGIUM Bermuda College Paget Bermuda PG04 Bermuda La Paz - Universidad Real La Paz BOLIVIA BOLIVIA GABORONE, BOTSWANA GABORONE BOTSWANA 0000 BOTSWANA Physique Tranformations Gaborone Southeast 0 Botswana BRASILIA, BRAZIL Brasilia DISTRITO FEDERAL 70673-150 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 31140-540 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 30160-011 BRAZIL CURITIBA, BRAZIL Curitiba PARANA 80060-205 BRAZIL RECIFE, BRAZIL Recife PERNAMBUCO 52020-220 BRAZIL RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Rio de Janeiro RIO DE JANEIRO 22050-001 BRAZIL SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Sao Paulo SAO PAULO 05690-000 BRAZIL SOFIA LAB 1, BULGARIA SOFIA BULGARIA 1000 SOFIA BULGARIA Bow Valley College Calgary ALBERTA T2G 0G5 Canada Calgary - MacLeod Trail S Calgary ALBERTA T2H0M2 CANADA SAIT Testing Centre Calgary ALBERTA T2M 0L4 Canada Edmonton AB Edmonton ALBERTA T5T 2E3 CANADA NorQuest College Edmonton ALBERTA T5J 1L6 Canada Vancouver Island University Nanaimo BRITISH COLUMBIA V9R 5S5 Canada Vancouver - Melville St. Vancouver BRITISH COLUMBIA V6E 3W1 CANADA Winnipeg - Henderson Highway Winnipeg MANITOBA R2G 3Z7 CANADA Academy of Learning - Winnipeg North Winnipeg MB R2W 5J5 Canada Memorial University of Newfoundland St. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination in the People's Republ

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA A REPORT BY HUMAN RIGHTS IN CHINA JULY 2001 Prepared to Assist in the Assessment of the Eighth and Ninth Periodic Report of the People抯 Republic of China on Implementation of the United Nation抯 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination This report was made possible by the support of the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) of which HRIC is an affiliate. It was funded, in part, by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office Human Rights Project Fund July 26, 2001 i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY厖厖厖…..厖厖厖厖厖厖厖厖厖… i I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 1 II. ASSESSMENT OF THE PRC GOVERNMENT REPORT ............................................... 3 A. “Minority Nationalities” an arbitrary construct .................................................................. 3 B. Gap between “law on books” and “reality” .......................................................................... 4 C. Analysis on situation of National Minorities......................................................................... 7 D. Information on domestic promotion of ICERD.................................................................... 7 III. DISCRIMINATION AGAINST RURAL RESIDENTS AND RURAL-TO-URBAN MIGRANTS.......................................................................................................................... -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

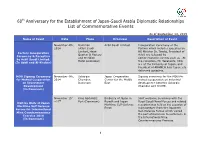

List of the Commemorative Events(PDF)

60th Anniversary for the Establishment of Japan-Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Relationships List of Commemorative Events As of September 14, 2015 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 4th, Damman Azbil Saudi Limited. Inauguration Ceremony of the 2014 (Azbil Saudi Factory which includes speeches by Limited, Head HE Minister Dr. Tawfig, President of Factory Inauguration Quarter & Factory Azbil, etc followed by Ceremony & Reception and Meridien commemorative events such as . At by Azbil Saudi Limited. Hotel Al-Khobar) the reception, Mr. Takahashi, CDA (In Azbil and Al-Khobar) a.i. at the Embassy of Japan, and President of ARAMCO Asia Japan, etc delivered speeches. MOU Signing Ceremony November 4th, Asharqia Japan Cooperation Signing ceremony for the MOU for for Mutual Cooperation 2014 Chamber, Center for the Middle mutual cooperation on industrial on Investment Dammam East development between Asharqia Development Chamber and JCCME. (In Dammam) November 15th King Abdulaziz Embassy of Japan in Joint welcome ceremony with the ~17th Port (Dammam) Riyadh and Japan Royal Saudi Naval Forces and related Visit by Units of Japan Maritime Self-Defense reception was held on the occasion of Maritime Self Defense Force minesweeper from the Japanese Forces for International Self-Defense Forces which visited Mine Countermeasures the port of Dammam to participate in Exercise 2014 the International Mine (In Dammam) Countermeasures Exercise. 1 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 18th King Fahd Cultural Embassy of Japan in The Embassy participated in the 7th ~22nd Center (Riyadh) Riyadh, Ministry of International Children’s Day Festival Culture and and showed a Japanese calligraphy, Participation to the 7th Information Origami, and Japanese traditional International Children’s garments. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 226/Monday, November 23, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 226 / Monday, November 23, 2020 / Notices 74763 antitrust plaintiffs to actual damages Fairfax, VA; Elastic Path Software Inc, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE under specified circumstances. Vancouver, CANADA; Embrix Inc., Specifically, the following entities Irving, TX; Fujian Newland Software Antitrust Division have become members of the Forum: Engineering Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, CHINA; Notice Pursuant to the National Communications Business Automation Ideas That Work, LLC, Shiloh, IL; IP Cooperative Research and Production Network, South Beach Tower, Total Software S.A, Cali, COLOMBIA; Act of 1993—Pxi Systems Alliance, Inc. SINGAPORE; Boom Broadband Limited, KayCon IT-Consulting, Koln, Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM; GERMANY; K C Armour & Co, Croydon, Notice is hereby given that, on Evolving Systems, Englewood, CO; AUSTRALIA; Macellan, Montreal, November 2, 2020, pursuant to Section Statflo Inc., Toronto, CANADA; Celona CANADA; Mariner Partners, Saint John, 6(a) of the National Cooperative Technologies, Cupertino, CA; TelcoDR, CANADA; Millicom International Research and Production Act of 1993, Austin, TX; Sybica, Burlington, Cellular S.A., Luxembourg, 15 U.S.C. 4301 et seq. (‘‘the Act’’), PXI CANADA; EDX, Eugene, OR; Mavenir Systems Alliance, Inc. (‘‘PXI Systems’’) Systems, Richardson, TX; C3.ai, LUXEMBOURG; MIND C.T.I. LTD, Yoqneam Ilit, ISRAEL; Minima Global, has filed written notifications Redwood City, CA; Aria Systems Inc., simultaneously with the Attorney San Francisco, CA; Telsy Spa, Torino, London, UNITED KINGDOM; -

1±21±2 1±21±2

Revue dramatickyÂch umenõ VydaÂva Kabinet divadla a filmu 1±21±2 1±21±2 Slovenskej akadeÂmie vied RocÏnõÂk 53 ± 2005 ± CÏõÂslo 1±2 OBSAH Hlavny redaktor: Andrej Mat'asÏõÂk RedakcÏna rada: MilosÏ MistrõÂk, JuÂlius PasÏteka, JaÂn SlaÂdecÏek, Ida HledõÂkovaÂ, SÏ TU DIE Karol HoraÂk, NadezÏda LindovskaÂ,JaÂn ZavarskyÂ, Miloslav Bla- hynka, Ladislav CÏ avojskyÂ, Jana Dutkova Ladislav CÏ avojskyÂ: MuzikaÂlovy BednaÂrik ............................... 3 Miloslav Blahynka: Esteticka analyÂza opery a jej mozÏnosti ................. 22 Dagmar InsÏtitorisovaÂ: O divadelnej konvencii .......................... 28 Anton Kret: Z esejõ ozaÂhadaÂch tvorby: Talent alebo Vystupovanie na Olymp .. 32 VladimõÂrSÏtefko: Zabudnuty rezÏiseÂr Ernest StrednÏansky .................. 36 Martin PaluÂch: Film ako zrkadlo subjektu I. ............................. 57 Elena KnopovaÂ: TajovskeÂho ZÏ ensky zaÂkon a Hasprov Tajovsky ............. 69 Technicka redaktorka: Jana JanõÂkova ROZHL' ADY Adresa redakcie: Kabinetdivadla a filmu SAV MilosÏ MistrõÂk: Sarah Kane ± samovrazÏda dialoÂgu ........................ 95 DuÂbravska cesta 9 Dagmar SabolovaÂ-Princic: Ako vypovedat'nevypovedane ................ 106 841 04 Bratislava Slovenska republika ROZHOVOR TelefoÂn: ++ 4212/ 54777193 Andrej Mat'asÏõÂk ± MatuÂsÏ Ol'ha: DivaÂk chodõ do divadla pre odpoved' Fax: ++ 4212/ 54777567 na otaÂzku ako zÏit' ............................................... 114 E-mail: [email protected] STATE Dagmar PodmakovaÂ: OpaÈt' o cÏloveku... na ceste ....................... -

A Structural Approach to the Arabian Nights

AWEJ. Special Issue on Literature No.2 October, 2014 Pp. 125- 136 A Structural Approach to The Arabian Nights Sura M. Khrais Department of English Language and Literature Princess Alia University College Al-Balqa Applied University Amman, Jordan Abstract This paper introduces a structural study of The Arabian Nights, Book III. The structural approach used by Vladimir Propp on the Russian folktales along with Tzvetan Todorov's ideas on the literature of the fantastic will be applied here. The researcher argues that structural reading of the chosen ten stories is fruitful because structuralism focuses on multiple texts, seeking how these texts unify themselves into a coherent system. This approach enables readers to study the text as a manifestation of an abstract structure. The paper will concentrate on three different aspects: character types, narrative technique and setting (elements of place). First, the researcher classifies characters according to their contribution to the action. Propp's theory of the function of the dramatist personae will be adopted in this respect. The researcher will discuss thirteen different functions. Then, the same characters will be classified according to their conformity to reality into historical, imaginative, and fairy characters. The role of the fairy characters in The Arabian Nights will be highlighted and in this respect Vladimir's theory of the fantastic will be used to study the significance of the supernatural elements in the target texts. Next, the narrative techniques in The Arabian Nights will be discussed in details with a special emphasis on the frame story technique. Finally, the paper shall discuss the features of place in the tales and show their distinctive yet common elements. -

Larry's Handy Dandy SOWPODS Wordolator

Larry's Handy Dandy SOWPODS Wordolator Words with Q not followed by U (84) BUQSHA BUQSHAS BURQA BURQAS FAQIR FAQIRS INQILAB INQILABS MBAQANGA MBAQANGAS MUQADDAM MUQADDAMS NIQAB NIQABS QABALA QABALAH QABALAHS QABALAS QABALISM QABALISMS QABALIST QABALISTIC QABALISTS QADI QADIS QAID QAIDS QAIMAQAM QAIMAQAMS QALAMDAN QALAMDANS QANAT QANATS QASIDA QASIDAS QAT QATS QAWWAL QAWWALI QAWWALIS QAWWALS QI QIBLA QIBLAS QIGONG QIGONGS QINDAR QINDARKA QINDARS QINGHAOSU QINGHAOSUS QINTAR QINTARS QIS QIVIUT QIVIUTS QOPH QOPHS QORMA QORMAS QWERTIES QWERTY QWERTYS SHEQALIM SHEQEL SHEQELS SUQ SUQS TALAQ TALAQS TRANQ TRANQS TSADDIQ TSADDIQIM TSADDIQS TZADDIQ TZADDIQIM TZADDIQS UMIAQ UMIAQS WAQF WAQFS YAQONA YAQONAS Words without Vowels (28) BRR BRRR CH CRWTH CRWTHS CWM CWMS CWTCH HM HMM MM NTH PFFT PHPHT PHT PSST PST SH SHH ST TSK TSKS TSKTSK TSKTSKS TWP ZZZ ZZZS Words with Vowels and One Consonant by Consanant (130) BEAU OBIA OBOE CIAO COOEE ACAI AECIA A DIEU IDEA IDEE ODEA AIDE AIDOI AUDIO EIDE OIDIA EUOI EUOUAE A GEE AGIO AGUE OGEE AIGA EUGE HIOI HUIA OHIA EUOI JIAO AJEE OUIJA KAIE KUIA AKEE LIEU LOOIE LOUIE LUAU ALAE ALEE ALOE ILEA ILIA OLEA OLEO OLIO AALII AULA AULOI EALE AIOLI MEOU MIAOU MOAI MOOI MOUE AMIA AMIE EMEU OUMA NAOI ANOA INIA ONIE UNAI UNAU AINE AINEE AUNE EINA EINE AEON EOAN EUOI EUOUAE PAUA EPEE OUPA QUAI QUEUE AQUA AQUAE RAIA ROUE AREA AREAE ARIA URAEI URAO UREA AERIE AERO AURA AURAE AUREI EERIE EURO IURE OORIE OURIE A SEA EASE OOSE AIAS EAUS TOEA ATUA ETUI AITU AUTO IOTA EUOI EUOUAE EUOUAE VIAE EVOE UVAE UVEA EAVE A WEE I XIA EAUX ZOAEA -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC