Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination in the People's Republ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC -

党和国家领导人重视民间外交工作 Party and State Leaders Attach Importance to People-To-People Diplomacy

fmfd-c5.indd 1 11-3-29 上午8:46 党和国家领导人重视民间外交工作 Party and State Leaders Attach Importance to People-to-people Diplomacy 寄希望于人民。 如果只有两国政府的合作 用民间外交的办法,不管 发展民间外交,有利于增 Hopes are placed on the people. 而没有民间交往,两国关系是 从历史上看,还是从现在看, 进各国人民的友谊,有利于促 不可能有扎实基础的。 都有非常重要的作用。 进各国经济、文化的交流和合 State relations would lack a solid China’s people-to-people diplomacy, 作,有利于为国家关系的发展 foundation if there were only governmental whether viewed from a historical cooperation but no people-to-people perspective or from the present, has 奠定广泛的社会群众基础。 contacts. played a very important role. To develop people-to-people diplomacy helps enhance friendship between the peoples, promote economic and cultural exchanges and cooperation among the countries and lay a broad social mass foundation for the development of state relations. 2-p1-11-s5.indd 1 11-3-29 上午8:47 前 言 中国人民对外友好协会成立于 1954 年 5 月,它是中华人民共和国 从事民间外交事业的全国性人民团体,以增进人民友谊、推动国际合 作、维护世界和平、促进共同发展为工作宗旨。它代表中国人民同各国 对华友好的团体和各界人士进行友好交往,在世界舞台上为中国人民的 正义事业争取国际同情,努力为国家总体外交、祖国建设与和平统一、 世界和谐服务。目前,我会与全国 300 多个地方友协密切合作,与世界 上 157 个国家的近 500 个民间团体和机构建立了友好合作关系,是沟通 中国人民和世界人民友谊的桥梁。 Foreword The Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries was established in May 1954. It is a national people’s organization engaged in people-to-people diplomacy of the People’s Republic of China. The aims of the Association are to enhance people-to-people friendship, further international cooperation, safeguard world peace, and promote common development. On behalf of the Chinese people, it makes friendly contacts with China-friendly organizations and personages of various circles in other countries, strives to gain international support for the just cause of the Chinese people on the world arena, and works in the interests of China’s total diplomacy, national construction and peaceful reunification and world harmony. -

In the Name of Pauk-Phaw

In the Name of Pauk-Phaw C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 00 Pauk Phaw Prelims.indd 2 8/23/11 1:14:51 PM In the Name of Pauk-Phaw Myanmar’s China Policy Since 1948 MAUNG AUNG MYOE INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE First published in Singapore in 2011 by Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 E-mail: [email protected] Website: <http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg> All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. © 2011 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore The responsibility for facts and opinions in this publication rests exclusively with the author and his interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or the policy of the publisher or its supporters. -

Political Succession and Leadership Issues in China: Implications for U.S

Order Code RL30990 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Political Succession and Leadership Issues in China: Implications for U.S. Policy Updated September 30, 2002 name redacted Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Political Succession and Leadership Issues in China: Implications for U.S. Policy Summary In 2002 and 2003, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will be making key leadership changes within the government and the Communist Party. A number of current senior leaders, including Party Secretary Jiang Zemin, Premier Zhu Rongji, and National Peoples’ Congress Chairman Li Peng, are scheduled to be stepping down from their posts, and it is not yet clear who will be assuming these positions from among the younger generation of leaders – the so-called “fourth generation,” comprised of those born in the 1940s and early 1950s. It is expected that new leaders will be ascending to positions at the head of at least two and possibly all three of the PRC’s three vertical political structures: the Chinese Communist Party; the state government bureaucracy; and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). During a period likely to last into 2003, the succession process remains very much in flux. Some who follow Beijing politics have raised questions about how vigorously China’s current senior leaders will adhere to their self-imposed term limitations. Party Secretary Jiang Zemin, for instance, is expected to try to keep his position as head of China’s military on the grounds that the global anti-terrorism campaign and internal challenges to Chinese rule create a special need now for consistent leadership. -

Mapping China Journal 2020

M A P P I N G C H I N A J O U R N A L 2 0 2 0 MAPPING CHINA JOURNAL 2020 J I E L I No 8 The 1990s Chinese Debates over Islamic Resurgence in Xinjiang by PRC Soviet- watchers ABSTRACT Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, China panicked and began to analyse the potential root causes. China, like the Soviet Union, is a multinational country with religious diversity. Chinese Soviet-watchers paid particular attention to the impact of the Islamic resurgence in the newly independent Central Asian republics on China’s Muslim populations in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Those writings tended to define the Xinjiang minorities fighting for religious freedom as political dissents opposing socialism. They also perceived that after the Soviet collapse, international forces would move against China. Xinjiang was seen as the most vulnerable to foreign conspiracies, owing to this Islamic resurgence and Western influence. These viewpoints justified the agenda of the CCP after the Cold War, when the Party believed that Western countries had a master plan to undermine China.To summarise, the debates of Chinese Soviet-watchers emphasized the importance of the Chinese government to take a firm hand in combating Xinjiang’s Islamic resurgence. The strategies that arose from these debates may inform readers of China’s present state policies and actions. AUTHOR Jie Li completed his PhD in History at the University of Edinburgh in 2017. His research covers many fields, including modern and contemporary Chinese history, China’s international relations since 1949, the histories of communism and the former Soviet Union, and the Cold War. -

The 16Th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Formal Institutions and Factional Groups ZHIYUE BO*

Journal of Contemporary China (2004), 13(39), May, 223–256 The 16th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: formal institutions and factional groups ZHIYUE BO* What was the political landscape of China as a result of the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)? The answer is two-fold. In terms of formal institutions, provincial units emerged as the most powerful institution in Chinese politics. Their power index, as measured by the representation in the Central Committee, was the highest by a large margin. Although their combined power index ranked second, central institutions were fragmented between central party and central government institutions. The military ranked third. Corporate leaders began to assume independent identities in Chinese politics, but their power was still negligible at this stage. In terms of informal factional groups, the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) Group was the most powerful by a large margin. The Qinghua Clique ranked second. The Shanghai Gang and the Princelings were third and fourth, respectively. The same ranking order also holds in group cohesion indexes. The CCYL Group stood out as the most cohesive because its group cohesion index for inner circle members alone was much larger than those of the other three factional groups combined. The Qinghua Clique came second, and the Shanghai Gang third. The Princelings was hardly a factional group because its group cohesion index was extremely low. These factional groups, nevertheless, were not mutually exclusive. There were significant overlaps among them, especially between the Qinghua Clique and the Shanghai Gang, between the Princelings and the Qinghua Clique, and between the CCYL Group and the Qinghua Clique. -

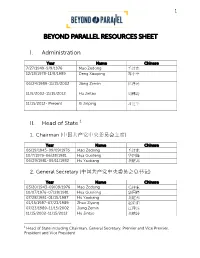

Beyond Parallel Resources Sheet

1 BEYOND PARALLEL RESOURCES SHEET I. Administration Year Name Chinese 7/27/1949-9/9/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 12/18/1978-11/8/1989 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 06/24/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/5/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 11/15/2012- Present Xi Jinping 习近平 II. Head of State 1 1. Chairman (中国共产党中央委员会主席) Year Name Chinese 06/19/1945-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/7/1976-06/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 06/29/1981-09/11/1982 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 2. General Secretary (中国共产党中央委员会总书记) Year Name Chinese 03/20/1943-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/07/1976-07/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 07/28/1981-01/15/1987 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 01/15/1987-07/23/1989 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 07/23/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/15/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 1 Head of State including Chairman, General Secretary, Premier and Vice Premier, President and Vice President 2 11/15/2012-Present Xi Jinping 习近平 3. Premier (中华人民共和国国务院总理) Year Name Chinese 10/1949-01/1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩来 2/2/1976-09/10/1980 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 09/10/1980-11/24/1987 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 11/24/1987-03/17/1998 Li Peng 李鹏 03/17/1998-03/16/2003 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/16/2003-03/15/2013 Wen Jiabao 温家宝 03/15/2013-Present Li Keqiang 李克强 4. Vice Premier (中华人民共和国国务院副总理) Year Name Chinese 09/15/1954-12/21/1964 Chen Yun 陈云 12/21/1964-09/13/1971 Lin Biao 林彪 09/13/1971-09/10/1980 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 09/10/1980-03/25/1988 Wan Li 万里 03/25/1988-3/05/1993 Yao Yilin 姚依林 3/25/1993-03/17/1998 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/17/1998-03/06/2003 Li Lanqing 李岚清 03/06/2003-06/02/2007 Huang Ju 黄菊 06/02/2007-03/16/2008 Wu Yi 吴仪 03/16/2008-03/16/2013 Li Keqiang 李克强 03/16/2013-Present Zhang Gaoli 张高丽 5. -

Local Leadership and Economic Development: Democratic India Vs

No. 24 | 2010 China Papers Local Leadership and Economic Development: Democratic India vs. Authoritarian China Bo Zhiyue China Papers ABSTRACT What is the impact of the type of political regime on economic development? Does democracy foster economic growth? Or is an authoritarian regime in a better position to promote material welfare? The conventional wisdom, as detailed in Adam Przeworski et al (2000), is that the regime type has no impact on economic growth. Democracy neither fosters nor hinders economic development. However, the cases of India and China seem to suggest otherwise. In the past three decades, India—the largest democracy in the world—has sustained a moderate rate of economic growth while China—the largest authoritarian regime— has witnessed an unprecedented period of economic expansion. Using data on economic growth at the state/provincial level from India and China, this study attempts to understand the impact of political regimes on economic development. The chapter will review the literature on regimes and economic development, highlight the contrast in economic growth between India and China in the past six decades, examine the two countries at the state/provincial level, and explore the impact of local leadership on economic development in a comparative framework. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Zhiyue BO is a Senior Research Fellow at the East Asian Institute of the National University of Singapore. China Papers Local Leadership and Economic Development: Democratic India vs. Authoritarian China Bo Zhiyue I. Introduction What is the impact of the type of political regime on economic development? Does democracy foster economic growth? Or is an authoritarian regime in a better position to promote material welfare? The conventional wisdom, as detailed in Adam Przeworski et al (2000),1 is that the regime type has no impact on economic growth. -

MEDIA and MINKAOHAN UYGHURS: REPRESENTATION, REACTION and RESISTANCE By

MEDIA AND MINKAOHAN UYGHURS: REPRESENTATION, REACTION AND RESISTANCE By LIANG ZHENG B.A., University of International Relations, l999 M.A., the Communication University of China, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Mass Communication 2011 This thesis entitled: Media and Minkaohan Uyghurs: Representation, Reaction, and Resistance written by Liang Zheng has been approved for the School of Journalism and Mass Communication Marguerite Moritz Bella Mody Nabil Echchaibi Timothy Weston James Millward Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # _0609.25_ iii Abstract Zheng, Liang (Ph.D., Communication, School of Journalism and Mass Communication) Media and Minkaohan Uyghurs: Representation, Reaction and Resistance Thesis directed by Professor Marguerite J. Moritz Chinese media have seen a grand transformation since the 1980s. However, the relationship between Chinese media and its 56 ethnic minority groups is under- researched. This dissertation intends to contribute to this field by examining media and in the context of the Uyghurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim people who reside in China’s far west Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Uyghurs number nine million, and consequently this research focuses on a sub-group of them: Minkaohan, who are ethnic Uyghurs who have attended Mandarin-language schools. This dissertation examines the post 9/11 representation of Uyghurs in Chinese state media and shows how Minkaoahan react to these portrayals. -

Cutting Off the Serpent=S Head

CUTTING OFF THE SERPENT===S HEAD: Tightening Control in Tibet, 1994-1995 Tibet Information Network Human Rights Watch/Asia ADVANCE READING COPY EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE MARCH 26, 1996 Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London $$$ Brussels ii Copyright 8 March 1996 by Tibet Information Network and Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-166-5 TIBET INFORMATION NETWORK The Tibet Information Network (TIN) is an independent news and research service that collects and distributes information about what is happening in Tibet. TIN monitors social, economic, political, environmental and human rights conditions in Tibet, and then publishes the information in an easily accessible form. It collects its information by using sources inside and outside Tibet, by conducting projects amongst refugees, and by monitoring established Chinese and international sources. TIN aims to present information that is accurate, reliable, and free from bias. Its material is available to subscribers who, in return for an annual fee, receive news updates and background briefing papers, as well as access to specialist briefings, translations of documents, and research services. The service is used by individuals and institutions, including journalists, governments, academics, China-watchers, and human rights organizations. TIN was started in 1987 and is based in London. It has no political affiliations or objectives and endeavors to provide a reliable and dispassionate news service for an area of increasing significance. TIN services include: - News Updates providing detailed coverage of news events - Background Briefing Papers on key social and political issues - Full texts of key interviews and original documents - Translations of articles from Tibetan newspapers - Briefings for delegations and analysts A selection of TIN information is translated into Tibetan, Japanese, German, French and Danish.