The Forced Migrations and Reorganisation of the Regional Order in the Caucasus by Safavid Iran: Preconditions and Developments Described by Fazli Khuzani*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthology of Georgian Poetry

ANTHOLOGY OF GEORGIAN POETRY Translated by VENERA URUSHADZE STATE PUBLISHING HOUSE «Soviet Georgia» Tbilisi 1958 PREFACE Nature and history have combined to make Georgia a land of poetry. Glistening peaks, majestic forests, sunny valleys, crystalline streams clamouring in deep gorges have a music of their own, which heard by the sensitive ear tends to breed poetic thought; while the incessant struggle of the Georgians against foreign invaders — Persians, Arabs, Mongols, Turks and others — has bred in them a sense of chivalry and a deep patriotism which found expression in many a lay, ballad and poem. Now the treasures of Georgian literature, both ancient and modern, are accessible to millions of our country's readers for they have been translated into many languages of the peoples of the Soviet Union. Except for the very few but beautiful translations of the Wardrops almost nothing has been translated from Georgian into English. The published works of Marjory Wardrop are — "Georgian Folk Tales", "The Hermit", a poem by Ilia Chavchavadze (included in this anthology), "Life of St. Nino", ''Wisdom and Lies" by Saba Sulkhan Orbeliani. But her chief work was the word by word translation of the great epic poem "The Knight in the Tiger's Skin" by Shota Rustaveli. Oliver Wardrop translated "Visramiani". Now, I have taken the responsibility upon myself to afford the English reader some of the treasures of Georgian poetry. This anthology, without pretending to be complete, aims at including the specimens of the varied poetry of the Georgian people from the beginning of its development till to-day. I shall not speak of the difficulties of translating into English from Georgian, even though it might serve as an excuse for some of my shortcomings. -

The Foundations of Russian (Foreign) Policy in the Gulf

Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a |w@_> retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B Gulf Research Center. ISBN: 9948-434-41-2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone and do not uG_GAE#'c`}A' state or reflect the opinions or position of the Gulf Research Center. i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' ,L ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA By publishing this volume, the Gulf Research Center (GRC) seeks to contribute to the enrichment of the reader’s knowledge out of the Center’s strong conviction that ‘knowledge is for all.’ Abdulaziz O. -

Archival and Source Studies – Trends and Challenges”

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE “ARCHIVAL AND SOURCE STUDIES – TRENDS AND CHALLENGES” 24-25 SEPTEMBER TBILISI 2020 THE CONFERENCE OPERATES: GEORGIAN AND ENGLISH TIME LIMIT: PRESENTATION: 15 MINUTES DEBATES: 5 MINUTES 24 SEPTEMBER OPENING SPEECHES FOR THE CONFERENCE - 09:00-09:30 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS AND ATTENDEES ARE WELCOMED BY: TEONA IASHVILI – GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF GEORGIA DAVID FRICKER – PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON ARCHIVES (ICA), DIRECTOR GENERAL OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF AUSTRALIA JUSSI NUORTEVA – GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF FINLAND CHARLES FARRUGIA – CHAIR OF THE EUROPEAN BRANCH OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON ARCHIVES (EURBICA), DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA ZAAL ABASHIDZE – DIRECTOR OF KORNELI KEKELIDZE NATIONAL CENTER OF MANUSCRIPTS RISMAG GORDEZIANI – DOCTOR OF PHILOLOGY VASIL KACHARAVA – PRESIDENT OF THE GEORGIAN ASSOCIATION FOR AMERICAN STUDIES 24 SEPTEMBER PART I 09:35 -18:10 MODERATORS: BESIK JACHVLIANI NINO BADASHVILI, SABA SALUASHVILI 09:35 - 09:55 THE EXPEDITION OF PUBLIUS CANIDIUS CRASSUS TO IBERIA (36 BC) Levan Tavlalashvili, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:00 - 10:20 CAUSES OF VIKING ATTACKS, ASPIRATION TO THE WEST (8TH-12TH CENTURIES) Mariam Gurgenidze, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:25 - 10:45 FOR THE ISSUES OF THE SOURCES ON THE HISTORY OF THE CRUSADERS Tea Gogolishvili, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:50 - 11:10 THE CULT OF MITHRAS IN GEORGIA Ketevan Kimeridze, The University of Georgia 11:15 - 11:35 -

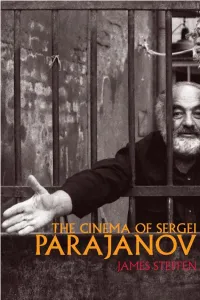

Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov Performs His Own Imprisonment for the Camera

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov performs his own imprisonment for the camera. Tbilisi, October 15, 1984. Courtesy of Yuri Mechitov. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov James Steffen The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711- 2059 uwpress.wisc .edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore .com Copyright © 2013 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Steffen, James. The cinema of Sergei Parajanov / James Steffen. p. cm. — (Wisconsin fi lm studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29654- 4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29653- 7 (e- book) 1. Paradzhanov, Sergei, 1924–1990—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Soviet Union. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin fi lm studies. PN1998.3.P356S74 2013 791.430947—dc23 2013010422 For my family. Contents List of Illustrations ix -

ROMANS SUTA's LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) from The

ROMANS SUTA’S LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) ROMANS SUTA’S LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) From the history of the later period of the life of a Latvian artist On the occasion of Romans Suta’s 120th birthday Nikolai Javakhishvili [email protected] The late period of life and activity of the famous Latvian painter, designer, and teacher Romans Suta (1896–1944) is connected with Georgia. The presented article dwells on Ro- mans Suta’s Tbilisi period and his nearest Georgian confreres. In the summer of 1941, Romans Suta came to Tbilisi. He started working in a Georgian movie studio as a painter. He has worked on movies: In Black Mountains (1941, Producer Nikoloz She n gelaia), Giorgi Saakadze (1942, Producer Mikhail Chiaureli), The Shield of Jurgai (1944, Pro du cers: Siko Dolidze and David Rondeli). Romans Suta’s successful career was stopped abruptly because of his arrest on 4 Sep- tember 1943. He was charged for being an “enemy of people” and for “faking bread cou- pons”. He was tried and sentenced to be shot on 14 July 1944. In 1959, Romans Suta was partly rehabilitated, because the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court exculpated Romans Suta’s charge of “enemy of people”, but “faking bread cards” still remained into effect. The article shows the real reasons for accusations to Romans Suta. The me moirs of his acquaintances, kept in the archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, prove that Romans Suta was a member of the Georgian anti-Soviet or ganisation “White George” (in Georgian, “Tetri Giorgi”). -

D44cd2a0faa8a3a05d7c152f4af

dokumenturi wyaroebi XVII saukunis I naxevris qarTlisa da kaxeTis mefeebis Sesaxeb I naSromi Sesrulebulia SoTa rusTavelis erovnuli samecniero fondis sagranto proeq- tis (FR17-554) farglebSi. winamdebare publika- ciaSi gamoTqmuli nebismieri mosazreba ekuT- vnis avtorebs da SesaZlebelia, ar asaxavdes korneli kekeliZis saxelobis saqarTvelos SoTa rusTavelis erovnuli samecniero fon- xelnawerTa erovnuli centri dis Sexedulebas. dokumenturi wyaroebi (sigelebi, epigrafikuli Zeglebi, xelnawerTa kolofonebi) XVII saukunis I naxevris qarTlisa da kaxeTis mefeebis (giorgi X, luarsab II, bagrat VII, svimon II, Teimuraz I) redaqtori: mzia surgulaZe Sesaxeb Targmani: rusudan labaZe (wyaroebis publikacia da gamokvleva) dizaini da dakabadoneba: daviT kvintraZe I am gamocemis arc erTi nawili aranairi formiT da saSualebiT, iqneba es eleqtronuli Tu meqanikuri, maT Soris fotopiris gadaRebiT da magnitur mowyobilobaze CaweriT, ar SeiZleba ga- moyenebul iqnas uflebebis mflobelTa winaswari werilobiTi Documentary Sources nebarTvis gareSe. (Deeds, Epigraphic Inscriptions, Colophons) daibeWda: gamomcemloba ~naTlismcemeli~ of the First Half of the 17th century about the Kings of Kartli and Kakheti (Giorgi X, Luarsab II, Bagrat VII, Svimon II, Teimuraz I) (research and publication of sources) I avtorebi: qarTveliSvili Tea (proeqtis samecniero xelmZRvaneli) bainduraSvili xaTuna, gelaSvili irakli, gogolaZe Tamaz, ISBN 978-9941-9677-7-1 (orive nawilis) SaorSaZe maia, jojua Temo ISBN 978-9941-9677-8-8 (pirveli nawilis) redaqtori mzia surgulaZe Tbilisi 2019 Sesavali (saistorio -

Monday 03 July 2017: 09.00-10.30

MONDAY 03 JULY 2017: 09.00-10.30 Session: 1 Great Hall KEYNOTE LECTURE 2017: THE MEDITERRANEAN OTHER AND THE OTHER MEDITERRANEAN: PERSPECTIVE OF ALTERITY IN THE MIDDLE AGES (Language: English) Nikolas P. Jaspert, Historisches Seminar, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg DRAWING BOUNDARIES: INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC SOCIETIES (Language: English) Eduardo Manzano Moreno, Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid Introduction: Hans-Werner Goetz, Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg Details: ‘The Mediterranean Other and the Other Mediterranean: Perspective of Alterity in the Middle Ages’: For many decades, the medieval Mediterranean has repeatedly been put to use in order to address, understand, or explain current issues. Lately, it tends to be seen either as an epitome of transcultural entanglements or - quite on the contrary - as an area of endemic religious conflict. In this paper, I would like to reflect on such readings of the Mediterranean and relate them to several approaches within a dynamic field of historical research referred to as ‘xenology’. I will therefore discuss different modalities of constructing self and otherness in the central and western Mediterranean during the High and Late Middle Ages. The multiple forms of interaction between politically dominant and subaltern religious communities or the conceptual challenges posed by trans-Mediterranean mobility are but two of the vibrant arenas in which alterity was necessarily both negotiated and formed during the medieval millennium. Otherness is however not reduced to the sphere of social and thus human relations. I will therefore also reflect on medieval societies’ dealings with the Mediterranean Sea as a physical and oftentimes alien space. -

Rızâyî-I Vânî (Ö. XVII Yy.?) Mecmû'ası Ve Haylî

Divan Edebiyatı Araştırmaları Dergisi 24, İstanbul 2020, 195-219. Rızâyî-i Vânî (ö. XVII yy.?) Mecmû‘ası ve Haylî (ö. 1040/1630-31)’nin Mavrav NUSRET GEDİK Hicviyyesi The Compilation of Rızayi Vani (d. in 17th Century) and Hayli’s (d. 1040/1630-31) Satire of Mavrav ÖZET ABSTRACT Şiir mecmuaları edebiyat tarihimizin ana kaynakları Poem compilations are considered as one of the main arasında yer almaktadır. Bu mecmualar; tezkirelerde adı sources of history of literature. These compilations usually geçmeyen, günümüze herhangi bir eseri ulaşamamış pek çok contain not only the poems, whose authors were not şairi ve bu şairlerin şiirlerini barındırdığı gibi çeşitli mentioned in poet biographies or poets, whose poems could dönemlerde sevilip okunan şairlerin yeni şiirlerini de ihtiva not make up to date, but also new poems of popular poets. edebilmektedir. Çalışmanın konusu XVII. yy. şairlerinden olup The subject of this study is the compilation of Rızâyî-i Vânî kaynaklarda hakkında herhangi bir bilgiye rastlayamadığımız who was one of the 17th century poets. There is no reference Rızâyî-i Vânî’nin tertip ettiği mecmuadır. Çeşitli Türk ve Fars about him in the sources. The compilation of Rızâyî-i Vânî, şairlerinin yanı sıra Rızâyî’nin kendi şiirlerini de barındıran besides various Turkish and Persian poems, includes a Rızâyî-i Vânî Mecmû‘ası, hiciv edebiyatına katkı yapacak bir satire, which would contribute the literature of satire. hicviyyeyi de içermektedir. Rızâyî, 1040/1630 Bağdat seferine Rızâyî probably copied the satire of Haylî during the katılan XVII yy. şairi Haylî’nin bu seferde nazmettiği 1040/1630 Bagdad Expedition which he attended at that hicviyyeyi büyük ihtimalle mahallinde mecmuasına aktarmış time. -

History of Iranian-Georgian Relation

IRANIAN HISTORY HISTORY OF IRANIAN-GEORGIAN RELATION By: Keith Hitchin Between the Achaemenid era and the beginning of the 19th century, Persia played a significant and at times decisive role in the history of the Georgian people. The Persian presence helped to shape political institutions, modified social structure and land holding, and enriched literature and culture. Persians also acted as a counterweight to other powerful forces in the region, notably the Romans (and Byzantines), the Ottoman Turks, and the Russians. But the Persian-Georgian relationship was by no means one-sided, for the Georgians contributed substantially to Persia's military and administrative successes and even affected its social structure, especially under the Safavids. Information about relations between the Achaemenids and the inhabitants of present-day Georgia is fragmentary. During the Achaemenid domination of eastern Anatolia and Transcaucasia (546-331 B.C.E.) proto-Georgian tribes were, according to Herodotus (3.94), included in the 18th and 19th satrapies (T. Kaukhchishvili, ed., pp. 10-11). Although the territory of present-day southern Georgia fell within the Achaemenid state, the Achaemenids apparently never brought those tribes living further to the north under their control. When they tried to do so their aggressiveness led to the formation of large associations of northern proto-Georgian tribes (Melikishvili, pp. 235, 273). Xenophon was aware of the changed conditions in 401-400 B.C.E. when he noted in the Anabasis that these tribes, including those of Colchis (q.v.), had ceased to be under Achaemenid rule (Mikeladze, ed., pp. 13-14). By this time proto-Georgians were moving into the Kura valley, where, merging with indigenous tribes, they eventually formed the Georgian people (Lang, 1966, pp. -

Tolerance in Multiethnic Georgia

The Foundation for Development of Human Resources Nodar Sarjveladze, Nino Shushania, Lia Melikishvili, Marina Baliashvili TOLERANCE IN MUltIETHNIC GEORGIA (Training Methodology Manual for Educators) Publishing house “Mtsignobari” Tbilisi 2009 Authors: Nodar Sarjveladze, Nino Shushania, Lia Melikishvili, Marina Baliashvili Design and binding: Irakli Geleishvili, Nato Shushania Translated by: Tina Chkheidze ISBN 978-9941-9079-2-0 First Georgian publication, 2009 © Foundation for Development of Human Resources, 2009 © Publishing house “Mtsignobari”, 2009 From the Authors This is a training manual on the management of interethnic relations inten- ded for teachers and youth leaders (educators). It also includes the description of the ethnic groups residing in Georgia and covers the themes like the nature of ethnic stereotypes and attitudes, peculiarities of intercultural dialogue, the essence of ethnic identity and conflicts. The suggested training system is based on the findings of the empirical research carried out with the teachers in the public schools of Georgia, youth leaders in patriot camps and future teachers. The system underwent an additional testing with 195 training participants. The given book can be useful to psychologists, students, ethnologists and those who are involved in the fields of education and interethnic relations. TAblE OF COntEnts PREFACE . 6 CHAPTER ONE Multiethnic Georgia . 11 The Azeri in Georgia . 12 Armenians in Georgia . 15 Ossetians in Georgia . 19 Greeks in Georgia . 22 Jews in Georgia . 24 Kurds in Georgia . 27 Assyrians in Georgia . 29 Lezgins in Georgia (Avars) . 31 Kists in Georgia . 33 Russians in Georgia . 36 Poles in Georgia . 40 Germans in Georgia . 42 Czechs in Georgia . 45 The Balts in Georgia . -

International Congress I Problems and Prospects Of

The Georgian National Academy of Sciences Iv. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Georgian Patriarchate INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS I PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS OF KARTVELOLOGY Tbilisi, 2015 ABSTRACTS 49 Zaza Alexidze (Georgia, Tbilisi) The Issue of Language and Statehood in Georgian Literature and Politics of Old and Recent Period 1. At the turn of IV-III centuries B.C., when King Parnavaz was establishing the first unitary Georgian State, the peak of the process was the declaration of Geor- gian as a State language and creation of the Georgian writing system. 2. In the early fourth century, when Iberia was left without a descendent of the Parnavazids, local nobles invited a certain Persian prince Mihran, in Georgia known as Mirian, as king. Mirian married the last female descendant of the Parnavazid dynasty, “he loved the Georgians, forgot Persian, learned Georgian and adorned the tomb of Parnavaz”. Georgian remained as Iberia’s state language. 3. In the VI-VII centuries, when the Kingdom of Kartli started to become unit- ed, church service in the borderline provinces of Georgia was conducted in the Georgian language even for the non-Georgian-speaking parish. This process of unifi- cation of the Georgian lands was known by the introduction of the unifying term “Entire Kartli” and the construction of the Cross Monastery near Mtskheta, “The Protector of the Entire Kartli”. 4. Due to Arab invasion, Georgia lost independence and fell into parts. However, in the X century the process of unification started anew. The Georgia of David the Builder and King Tamar was gradually developing. Based on the 13-centuries’ experience, a genius Georgian scholar expressed a simple and clear idea: “Kartli is the land where the liturgy is performed in Georgian and all prayers are said in the Georgian language”. -

Generational Difference in Understanding Georgian National Identity and the Other

GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCE IN UNDERSTANDING GEORGIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE OTHER by Ellen Galdava A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Generational Difference in Understanding Georgian National Identity and The Other A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University By Ellen Galdava Bachelor of Arts American University in Bulgaria, 2012 Director: Daniel Rothbart, Professor School of Conflict Analysis and Resolution Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2015 Ellen Galdava All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my husband Giorgi, my family, and to my country. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee, family, respondents, and supporters who have made this happen. I want to thank my husband, Giorgi Maisuradze and Claudine Kuradusenge, for moral support. Dr. Karyna V. Korostelina for guidance and recommendations.