Frontier Orientalism and the Stereotype Formation Process in Georgian Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Report of Georgia (MOP7)

Report on the implementation of AEWA for the period 2015-2017 The format for reports on the implementation of the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) for the period 2015-2017 was approved at the 12th meeting of the Standing Committee (31 January – 01 February 2017, Paris, France). This format has been constructed following the AEWA Action Plan, the AEWA Strategic Plan 2009-2018 and resolutions of the Meeting of the Parties (MOP). In accordance with article V(c) of the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, each Party shall prepare to each ordinary session of the MOP a National Report on its implementation of the Agreement and submit that report to the Agreement Secretariat. By Resolution 6.14 of the MOP the deadline for submission of National Reports to the 7th session of the Meeting of the Parties (MOP7) was set at 180 days before the beginning of MOP7, which is scheduled to take place on 4 – 8 December 2018 in South Africa; therefore the deadline for submission of National Reports is Wednesday 7 June 2018. The AEWA National Reports 2015-2017 will be compiled and submitted through the CMS Family Online National Reporting System, which is an online reporting tool for the whole CMS Family. The CMS Family Online Reporting System was developed by the UNEP-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) in close collaboration with and under the guidance of the UNEP/AEWA Secretariat. To contact the UNEP/AEWA Secretariat please send your inquiries to: [email protected] 1. -

The Forced Migrations and Reorganisation of the Regional Order in the Caucasus by Safavid Iran: Preconditions and Developments Described by Fazli Khuzani*

The Forced Migrations and Reorganisation of the Regional Order in the Caucasus by Safavid Iran: Preconditions and Developments Described by Fazli Khuzani* MAEDA Hirotake Introduction Two centuries of Safavid rule over the Iranian highlands from the 16th to 18th centuries brought about a substantial change in the indigenous society. Shia Islam became the state religion and rivalry with neighboring powers (Ottomans and Uzbeks) gives a certain socio-political distinction. During this period territorial integrity was also achieved to some extent as a result of the reformations of Shāh ‘Abbās I (reign 995/1587–1038/1629). He moved the capital to E≠fahān, an old city situated in central Iran and made the heart of the Iranian plateau crown land. Military reform was inevitable to strengthen the central authority facing danger both externally and at home. Shāh ‘Abbās incorporated the royal slaves gholāmān-e khā≠≠e-ye sharīfe=hereafter gholāms) into the state administration and this new elite corps mainly consisted of Caucasian converts who contributed much to the creation of a stable regime which replaced the tribal state.1 The Safavid gholāms were traditionally regarded as absolute slaves who had lost any previous identity and were totally dependent on the Shāh. * This paper was delivered at the conference ‘Reconstruction and Interaction of Slavic Eurasia and Its Neighboring Worlds’ held by the Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, in Sapporo, December 8–10, 2004 (Session 9: Power, Identity and Regional Restructuring in the Caucasus, December 10). I thank the participants and the audience for their valuable comments. Especially comments by Prof. Kitagawa (Tohoku University) are reflected in the following notes. -

Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr

UDC 9 (479.22) 34 Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr. Levan Z. Urushadze (Tbilisi, Georgia) ISBN 99940-0-539-1 The Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG. “Sakartvelos Demokratiuli Respublika” in Georgian) was the first modern establishment of a Republic of Georgia in 1918 - 1921. The DRG was established after the collapse of the Russian Tsarist Empire that began with the Russian Revolution of 1917. Its established borders were with Russia in the north, and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in the south. It had a total land area of roughly 107,600 km2 (by comparison, the total area of today's Georgia is 69,700 km2), and a population of 2.5 million. As today, its capital was Tbilisi and its state language - Georgian. THE NATIONAL FLAG AND COAT OF ARMS OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA A Trans-Caucasian house of representatives convened on February 10, 1918, establishing the Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic, which existed from February, 1918 until May, 1918. The Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic was managed by the Trans-Caucasian Commissariat chaired by representatives of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. On May 26, 1918 this Federation was abolished and Georgia declared its independence. Politics In February 1917, in Tbilisi the first meeting was organised concerning the future of Georgia. The main organizer of this event was an outstanding Georgian scientist and public benefactor, Professor Mikheil (Mikhako) Tsereteli (one of the leaders of the Committee -

Armed Forces of Georgian Democratic Republic in 1918–1921

George Anchabadze Armed Forces of Georgian Democratic Republic .. DOI: http://doi.org/10.22364/luzv.5.06 Armed Forces of Georgian Democratic Republic in 1918–1921 Gruzijas Demokrātiskās Republikas bruņotie spēki 1918.–1921. gadā George Anchabadze, Doctor of History Sciences, Full professor Ilia State University, School of Arts and Sciences Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia E-mail: [email protected] The article is dedicated to the armed forces of the Georgian Democratic Republic (1918–1921). It shows the history of their creation and development, the composition and structure of the troops, as well as provides a brief insight into the combat path. It also shows the contradictions that existed between the socialist leadership of the country and a significant part of the officer corps, caused by ideological differences. The result of these contradictions were two forms of the armed organization of Georgia – the regular army and the People’s Guard, which caused discord in the armed forces. This circumstance, among other reasons, contributed to the military defeat of Georgia in the clash with Soviet Russia (1921). Keywords: Transcaucasia in 1918–1921, Georgian Democratic Republic, regular army of Georgia, the People’s Guard, The Soviet-Georgian War of 1921. Raksts veltīts Gruzijas Demokrātiskās Republikas bruņotajiem spēkiem 1918.–1921. gadā, tajā atspoguļota to izveidošanas un attīstības vēsture, kā arī karaspēka sastāvs un struktūra, bez tam īsumā raksturotas kaujas operācijas. Parādītas arī pretrunas, kas pastāvēja starp valsts sociālistisko vadību un lielu daļu virsnieku korpusa un kas izraisīja ideoloģiskas atšķirības. Šo pretrunu rezultāts bija divas Gruzijas bruņoto spēku organizatoriskās formas – regulārā armija un Tautas gvarde –, starp kurām pastāvēja nesaskaņas. -

Anthology of Georgian Poetry

ANTHOLOGY OF GEORGIAN POETRY Translated by VENERA URUSHADZE STATE PUBLISHING HOUSE «Soviet Georgia» Tbilisi 1958 PREFACE Nature and history have combined to make Georgia a land of poetry. Glistening peaks, majestic forests, sunny valleys, crystalline streams clamouring in deep gorges have a music of their own, which heard by the sensitive ear tends to breed poetic thought; while the incessant struggle of the Georgians against foreign invaders — Persians, Arabs, Mongols, Turks and others — has bred in them a sense of chivalry and a deep patriotism which found expression in many a lay, ballad and poem. Now the treasures of Georgian literature, both ancient and modern, are accessible to millions of our country's readers for they have been translated into many languages of the peoples of the Soviet Union. Except for the very few but beautiful translations of the Wardrops almost nothing has been translated from Georgian into English. The published works of Marjory Wardrop are — "Georgian Folk Tales", "The Hermit", a poem by Ilia Chavchavadze (included in this anthology), "Life of St. Nino", ''Wisdom and Lies" by Saba Sulkhan Orbeliani. But her chief work was the word by word translation of the great epic poem "The Knight in the Tiger's Skin" by Shota Rustaveli. Oliver Wardrop translated "Visramiani". Now, I have taken the responsibility upon myself to afford the English reader some of the treasures of Georgian poetry. This anthology, without pretending to be complete, aims at including the specimens of the varied poetry of the Georgian people from the beginning of its development till to-day. I shall not speak of the difficulties of translating into English from Georgian, even though it might serve as an excuse for some of my shortcomings. -

The Foundations of Russian (Foreign) Policy in the Gulf

Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a |w@_> retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B Gulf Research Center. ISBN: 9948-434-41-2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone and do not uG_GAE#'c`}A' state or reflect the opinions or position of the Gulf Research Center. i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' ,L ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA By publishing this volume, the Gulf Research Center (GRC) seeks to contribute to the enrichment of the reader’s knowledge out of the Center’s strong conviction that ‘knowledge is for all.’ Abdulaziz O. -

Download(PDF)

ԵՐԵՎԱՆԻ ՊԵՏԱԿԱՆ ՀԱՄԱԼՍԱՐԱՆ ՔԱՂԱՔԱԿՐԹԱԿԱՆ ԵՎ ՄՇԱԿՈՒԹԱՅԻՆ ՀԵՏԱԶՈՏՈՒԹՅՈՒՆՆԵՐԻ ԿԵՆՏՐՈՆ Վերլուծական տեղեկագիր ՀԱՅ-ՎՐԱՑԱԿԱՆ ԱԿԱԴԵՄԻԱԿԱՆ ԵՒ ՈՒՍԱՆՈՂԱԿԱՆ ՀԱՄԱԳՈՐԾԱԿՑՈՒԹՅՈՒՆ № 10 Երևան – 2017 YEREVAN STATE UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR CIVILIZATION AND CULTURAL STUDIES Analytical Bulletin ARMENIAN-GEORGIAN COOPERATION THROUGH ACADEMIA AND STUDENTS’ INCLUSION № 10 Yerevan 2017 ISSN 1829-4502 Հրատարակվում է ԵՊՀ Քաղաքակրթական և մշակութային հետազոտությունների կենտրոնի գիտական խորհրդի որոշմամբ Խմբագրական խորհուրդ՝ Դավիթ Հովհաննիսյան բ.գ.թ., պրոֆեսոր, Արտակարգ և լիազոր դեսպան (նախագահ) Արամ Սիմոնյան պ.գ.դ., պրոֆեսոր, ՀՀ ԳԱԱ թղթակից-անդամ, Ռուբեն Սաֆրաստյան պ.գ.դ., պրոֆեսոր, ՀՀ ԳԱԱ ակադեմիկոս Արման Կիրակոսյան պ.գ.դ., պրոֆեսոր, Արտակարգ և լիազոր դեսպան Ռուբեն Շուգարյան պ.գ.թ., Ֆլեթչերի իրավունքի և դիվանագիտության դպրոց, Թաֆթս համալսարան (ԱՄՆ) Աննա Օհանյան քաղ.գ.դ. քաղաքագիտության և միջազգային հարաբերությունների պրոֆեսոր, Սթոնհիլ Քոլեջ (ԱՄՆ) Սերգեյ Մինասյան քաղ.գ.դ. Քեթևան Խուցիշվիլի մարդ.գ.դ. (Վրաստան) Հայկ Քոչարյան պ.գ.թ., դոցենտ Սաթենիկ Մկրտչյան պ.գ.թ., (համարի պատասխանատու) © Քաղաքակրթական և մշակութային հետազոտությունների կենտրոն‚ 2017 © Երևանի պետական համալսարան‚ 2017 ISSN 1829-4502 Published by Scientific council of Center for Civilization and Cultural Studies Editorial Board David Hovhannisyan Professor and Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Aram Simonyan Doctor Professor, Corresponding member of the Academy of Science of Armenia Ruben Safrastyan Doctor Professor, member of Academy of Science of Armenia Arman Kirakosyan Doctor Professor and Ambassador -

Archival and Source Studies – Trends and Challenges”

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE “ARCHIVAL AND SOURCE STUDIES – TRENDS AND CHALLENGES” 24-25 SEPTEMBER TBILISI 2020 THE CONFERENCE OPERATES: GEORGIAN AND ENGLISH TIME LIMIT: PRESENTATION: 15 MINUTES DEBATES: 5 MINUTES 24 SEPTEMBER OPENING SPEECHES FOR THE CONFERENCE - 09:00-09:30 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS AND ATTENDEES ARE WELCOMED BY: TEONA IASHVILI – GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF GEORGIA DAVID FRICKER – PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON ARCHIVES (ICA), DIRECTOR GENERAL OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF AUSTRALIA JUSSI NUORTEVA – GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF FINLAND CHARLES FARRUGIA – CHAIR OF THE EUROPEAN BRANCH OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON ARCHIVES (EURBICA), DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA ZAAL ABASHIDZE – DIRECTOR OF KORNELI KEKELIDZE NATIONAL CENTER OF MANUSCRIPTS RISMAG GORDEZIANI – DOCTOR OF PHILOLOGY VASIL KACHARAVA – PRESIDENT OF THE GEORGIAN ASSOCIATION FOR AMERICAN STUDIES 24 SEPTEMBER PART I 09:35 -18:10 MODERATORS: BESIK JACHVLIANI NINO BADASHVILI, SABA SALUASHVILI 09:35 - 09:55 THE EXPEDITION OF PUBLIUS CANIDIUS CRASSUS TO IBERIA (36 BC) Levan Tavlalashvili, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:00 - 10:20 CAUSES OF VIKING ATTACKS, ASPIRATION TO THE WEST (8TH-12TH CENTURIES) Mariam Gurgenidze, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:25 - 10:45 FOR THE ISSUES OF THE SOURCES ON THE HISTORY OF THE CRUSADERS Tea Gogolishvili, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 10:50 - 11:10 THE CULT OF MITHRAS IN GEORGIA Ketevan Kimeridze, The University of Georgia 11:15 - 11:35 -

Soviet-Georgian War and Sovietization of Georgia, II-III. 1921

Soviet-Georgian War and Sovietization of Georgia, II-III. 1921 La guerre soviéto-géorgienne et la soviétisation de la Géorgie (février-mars 1921) By Andrew Andersen and George Partskhaladze Revue historique des Armées Numéro 254, 1/2009 Photographs: private archive of Levan Urushadze Introduction In the year 1918, Georgia restored her independence from the Russian Empire. This became possible as a result of World War I - which endorsed a tremendous pressure on states with weak economies and social structure - one of which was Russia. Military defeat in combination with both economic and political failure, led to the collapse of the empire, undermined by the devastating war, and eventually led to the Revolution of 1917, as well as the establishment of a Bolshevik dictatorship in former the imperial centres, the civil war and secession of non-Russian peripheries. Initially, the Georgian elites were reluctant to separate from Russia. However, the disintegration of the Caucasus front, and the threat of invasions and chaos, forced them to build a state in an attempt to protect Georgia from both military and political challenges from the Bolsheviks, anti- Bolsheviks and the Turks, who claimed dominance over the South Caucasus. Azerbaijan and Armenia followed Georgia’s example1. Military parade in Tbilisi, January/1921 During the three years of independence, Georgia’s moderate socialist leadership were rather successful in the establishment of a democracy-track society with universal suffrage, democratically-elected legislature, freedom of speech and tolerance to both right- and left-wing opposition2. However, the development of democratic processes in the First Republic faced a 1 Stephen F. -

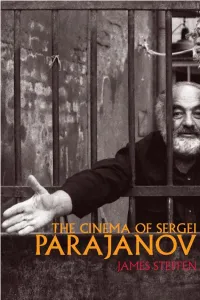

Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov Performs His Own Imprisonment for the Camera

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov performs his own imprisonment for the camera. Tbilisi, October 15, 1984. Courtesy of Yuri Mechitov. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov James Steffen The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711- 2059 uwpress.wisc .edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore .com Copyright © 2013 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Steffen, James. The cinema of Sergei Parajanov / James Steffen. p. cm. — (Wisconsin fi lm studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29654- 4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29653- 7 (e- book) 1. Paradzhanov, Sergei, 1924–1990—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Soviet Union. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin fi lm studies. PN1998.3.P356S74 2013 791.430947—dc23 2013010422 For my family. Contents List of Illustrations ix -

ROMANS SUTA's LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) from The

ROMANS SUTA’S LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) ROMANS SUTA’S LIFE TBILISI PERIOD (1941–1944) From the history of the later period of the life of a Latvian artist On the occasion of Romans Suta’s 120th birthday Nikolai Javakhishvili [email protected] The late period of life and activity of the famous Latvian painter, designer, and teacher Romans Suta (1896–1944) is connected with Georgia. The presented article dwells on Ro- mans Suta’s Tbilisi period and his nearest Georgian confreres. In the summer of 1941, Romans Suta came to Tbilisi. He started working in a Georgian movie studio as a painter. He has worked on movies: In Black Mountains (1941, Producer Nikoloz She n gelaia), Giorgi Saakadze (1942, Producer Mikhail Chiaureli), The Shield of Jurgai (1944, Pro du cers: Siko Dolidze and David Rondeli). Romans Suta’s successful career was stopped abruptly because of his arrest on 4 Sep- tember 1943. He was charged for being an “enemy of people” and for “faking bread cou- pons”. He was tried and sentenced to be shot on 14 July 1944. In 1959, Romans Suta was partly rehabilitated, because the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court exculpated Romans Suta’s charge of “enemy of people”, but “faking bread cards” still remained into effect. The article shows the real reasons for accusations to Romans Suta. The me moirs of his acquaintances, kept in the archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, prove that Romans Suta was a member of the Georgian anti-Soviet or ganisation “White George” (in Georgian, “Tetri Giorgi”). -

Inf.EUROBATS.24.3.Rev.1

Inf.EUROBATS.AC24.3.Rev.1 24th Meeting of the Advisory Committee Skopje, North Macedonia, 1 – 3 April 2019 Provisional List of Participants PARTIES ALBANIA CROATIA Prof. Ferdinand Bego Ms. Daniela Hamidović University of Tirana Ministry of Environment and Energy Faculty of Natural Sciences Radnička cesta 80/7 Department of Biology 10000 Zagreb Blv. Zogu I, No. 25/1 Tirana CZECH REPUBLIC Dr. Aurora Dibra Ms. Libuše Vlasáková University of Shkodër “Luigj Gurakuqi” Ministry of the Environment Faculty of Natural Sciences Vršovická 65 Department of Biology and Chemistry 10010 Prague 10 Sheshi 2 Prilli Dr. Helena Jahelková 4001-4007 Shkodër Čihadla 394 252 31 Všenory BELGIUM Dr. Ludo Holsbeek ESTONIA Flemish Government Ms. Kaja Lotman Department of Environment and Spatial Environmental Board of Estonia Planning Narva Mnt 7a Ferraris building, 5G067 15172 Tallinn Koning Albert-II laan 20 bus 8 1000 Brussels Mr. Lauri Lutsar Estonian Fund for Nature Dr. Thierry Kervyn Lai 29 Service public de Wallonie DGO3-DEMNA 51005 Tartu Avenue Maréchal Juin 23 5030 Gembloux FINLAND BULGARIA Ms. Kati Suominen Finnish Museum of Natural History Mr. Ilya Acosta Pankov Pohjoinen Rautatiekatu 13 National Museum of Natural History 00014 University of Helsinki Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Tsar Osvoboditel Blvd. 1 1000 Sofia - 1 - FRANCE LATVIA Professor Stéphane Aulagnier Dr. Gunars Petersons Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse III Latvian University of Life Sciences and Comportement et Ecologie de la Technologies Faune Sauvage (CEFS) Faculty of Veterinary Medicine INRA K Helmana Str. 8 CS 52627 3004 Jelgava 31326 Castanet-Tolosan Cedex LUXEMBOURG GEORGIA Mr. Jacques B. Pir Mr. Ioseb Natradze Ministère de l’Environnement, du Climat Field Researchers’ Union “Campester” et du Développement durable Tamarashvili 2a, Apt 6 p/a Département de l’Environnement 0162 Tbilisi 4, place de l’Europe Institute of Zoology of Ilia State University 2918 Luxembourg Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5 0162 Tbilisi MOLDOVA Dr.