Current Women's Health Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prolactin Level in Women with Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Visiting Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in a University Teaching Hospital in Ajman, UAE

Prolactin level in women with Abnormal Uterine Bleeding visiting Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in a University teaching hospital in Ajman, UAE Jayakumary Muttappallymyalil1*, Jayadevan Sreedharan2, Mawahib Abd Salman Al Biate3, Kasturi Mummigatti3, Nisha Shantakumari4 1Department of Community Medicine, 2Statistical Support Facility, CABRI, 4Department of Physiology, Gulf Medical University, Ajman, UAE 3Department of OBG, GMC Hospital, Ajman, UAE *Presenting Author ABSTRACT Objective: This study was conducted among women in the reproductive age group with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to determine the pattern of prolactin level. Materials and Methods: In this study, a total of 400 women in the reproductive age group with AUB attending GMC Hospital were recruited and their prolactin levels were evaluated. Age, marital status, reproductive health history and details of AUB were noted. SPSS version 21 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics was performed to describe the population, and inferential statistics such as Chi-square test was performed to find the association between dependent and independent variables. Results: Out of 400 women, 351 (87.8%) were married, 103 (25.8%) were in the age group 25 years or below, 213 (53.3%) were between 26-35 years and 84 (21.0%) were above 35 years. Mean age was 30.3 years with a standard deviation 6.7. The prolactin level ranged between 15.34 mIU/l and 2800 mIU/l. The mean and SD observed were 310 mIU/l and 290 mIU/l respectively. The prolactin level was high among AUB patients with inter-menstrual bleeding compared to other groups. Additionally, the level was high among women with age greater than 25 years compared to those with age less than or equal to 25 years. -

Te2, Part Iii

TERMINOLOGIA EMBRYOLOGICA Second Edition International Embryological Terminology FIPAT The Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology A programme of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) TE2, PART III Contents Caput V: Organogenesis Chapter 5: Organogenesis (continued) Systema respiratorium Respiratory system Systema urinarium Urinary system Systemata genitalia Genital systems Coeloma Coelom Glandulae endocrinae Endocrine glands Systema cardiovasculare Cardiovascular system Systema lymphoideum Lymphoid system Bibliographic Reference Citation: FIPAT. Terminologia Embryologica. 2nd ed. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology, February 2017 Published pending approval by the General Assembly at the next Congress of IFAA (2019) Creative Commons License: The publication of Terminologia Embryologica is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0) license The individual terms in this terminology are within the public domain. Statements about terms being part of this international standard terminology should use the above bibliographic reference to cite this terminology. The unaltered PDF files of this terminology may be freely copied and distributed by users. IFAA member societies are authorized to publish translations of this terminology. Authors of other works that might be considered derivative should write to the Chair of FIPAT for permission to publish a derivative work. Caput V: ORGANOGENESIS Chapter 5: ORGANOGENESIS -

Adenomyosis in Infertile Women: Prevalence and the Role of 3D Ultrasound As a Marker of Severity of the Disease J

Puente et al. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2016) 14:60 DOI 10.1186/s12958-016-0185-6 RESEARCH Open Access Adenomyosis in infertile women: prevalence and the role of 3D ultrasound as a marker of severity of the disease J. M. Puente1*, A. Fabris1, J. Patel1, A. Patel1, M. Cerrillo1, A. Requena1 and J. A. Garcia-Velasco2* Abstract Background: Adenomyosis is linked to infertility, but the mechanisms behind this relationship are not clearly established. Similarly, the impact of adenomyosis on ART outcome is not fully understood. Our main objective was to use ultrasound imaging to investigate adenomyosis prevalence and severity in a population of infertile women, as well as specifically among women experiencing recurrent miscarriages (RM) or repeated implantation failure (RIF) in ART. Methods: Cross-sectional study conducted in 1015 patients undergoing ART from January 2009 to December 2013 and referred for 3D ultrasound to complete study prior to initiating an ART cycle, or after ≥3 IVF failures or ≥2 miscarriages at diagnostic imaging unit at university-affiliated private IVF unit. Adenomyosis was diagnosed in presence of globular uterine configuration, myometrial anterior-posterior asymmetry, heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, poor definition of the endometrial-myometrial interface (junction zone) or subendometrial cysts. Shape of endometrial cavity was classified in three categories: 1.-normal (triangular morphology); 2.- moderate distortion of the triangular aspect and 3.- “pseudo T-shaped” morphology. Results: The prevalence of adenomyosis was 24.4 % (n =248)[29.7%(94/316)inwomenaged≥40 y.o and 22 % (154/ 699) in women aged <40 y.o., p = 0.003)]. Its prevalence was higher in those cases of recurrent pregnancy loss [38.2 % (26/68) vs 22.3 % (172/769), p < 0.005] and previous ART failure [34.7 % (107/308) vs 24.4 % (248/1015), p < 0.0001]. -

Association of the Rectovestibular Fistula with MRKH Syndrome And

Association of the rectovestibular fistula with MRKH Syndrome and the paradigm Review Article shift in the management in view of the future uterine transplant © 2020, Sarin YK Yogesh Kumar Sarin Submitted: 15-06-2020 Accepted: 30-09-2020 Director Professor & Head Department of Pediatric Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, INDIA License: This work is licensed under Correspondence*: Dr. Yogesh Kumar Sarin, Director Professor & Head Department of Pediatric Surgery, Lady a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India, E-mail: [email protected] International License. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47338/jns.v9.551 KEYWORDS ABSTRACT Rectovestibular fistula, Uterine transplantation in Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster̈ -Hauser (MRKH) patients with absolute Vaginal atresia, uterine function infertility have added a new dimension and paradigm shift in the Cervicovaginal atresia, management of females born with rectovestibular fistula coexisting with vaginal agenesis. MRKH Syndrome, The author reviewed the relevant literature of this rare association, the popular and practical Vaginoplasty, Bowel vaginoplasty, classifications of genital malformations that the gynecologists use, the different vaginal Ecchietti vaginoplasty, reconstruction techniques, and try to know what shall serve best in this small cohort of Uterine transplantation, these patients lest they wish to go for uterine transplantation in future. VCUA classification, ESHRE/ESGE classification, AFC classification, Krickenbeck classification INTRODUCTION -

Sample-11060.Pdf

Ob/Gyn Sonography An Illustrated Review 2nd Edition Jim Baun, BS, RDMS, RVT, FSDMS Professional Ultrasound Services San Francisco, California SPECIALISTS IN ULTRASOUND EDUCATION, TEST PREPARATION, AND CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION iv SPECIALISTSCopyright IN ULTRASOUND © 2016, EDUCATION, 2004 by Davies Publishing, Inc. TEST PREPARATION, AND CONTINUINGAll rights MEDICAL reserved. EDUCATION No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. Davies Publishing, Inc. Michael Davies, Publisher Specialists in Ultrasound Education, Christina J. Moose, Editorial Director Test Preparation, and Continuing Charlene Locke, Production Manager Medical Education Janet Heard, Operations Manager 32 South Raymond Avenue Pasadena, California 91105-1961 Jim Baun, Illustration Phone 626-792-3046 Stephen Beebe, Illustration Facsimile 626-792-5308 Satori Design Group, Inc., Design Email [email protected] www.daviespublishing.com Notice to Users of This Publication: In the field of ultrasonography, knowledge, technique, and best practices are continually evolving. With new research and developing technologies, changes in methodologies, professional prac- tices, and medical treatment may become necessary. Sonography practitioners and other medi- cal professionals and researchers must rely on their experience and knowledge when evaluating and using information, methods, -

The Prevalence of and Attitudes Toward Oligomenorrhea and Amenorrhea in Division I Female Athletes

POPULATION-SPECIFIC CONCERNS The Prevalence of and Attitudes Toward Oligomenorrhea and Amenorrhea in Division I Female Athletes Karen Myrick, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, Richard Feinn, PhD, and Meaghan Harkins, MS, BSN, RN • Quinnipiac University Research has demonstrated that amenor- hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone rhea and oligomenorrhea may be common shut down stimulation to the ovary, ceasing occurrences among female athletes.1 Due production of estradiol.2 to normalization of menstrual dysfunction The effect of oral contraceptives on the within the sport environment, amenorrhea menstrual cycle include ovulation inhibi- and oligomenorrhea tion, changes in cervical mucus, thinning may be underreported. of the uterine endometrium, and motility Key PointsPoints There are many underly- and secretion in the fallopian tubes, which Lean sport athletes are more likely to per- ing causes of menstrual decrease the likelihood of conception and 3 ceive missed menstrual cycles as normal. dysfunction. However, implantation. Oral contraceptives contain a a similar hypothalamic combination of estrogen and progesterone, Menstrual dysfunction is one prong of the amenorrhea profile is or progesterone only; thus, oral contracep- female athlete triad. frequently seen in ath- tives do not stop the production of estrogen. letes, and hypothalamic Menstrual dysfunction is one prong of the Menstrual dysfunction is often associated dysfunction is com- female athlete triad (triad). The triad is a with musculoskeletal and endothelial monly the root of ath- syndrome of linking low energy availability compromise. lete’s menstrual abnor- (EA) with or without disordered eating, men- malities.2 The common strual disturbances, and low bone mineral Education and awareness of the accultur- hormone pattern for density, across a continuum. -

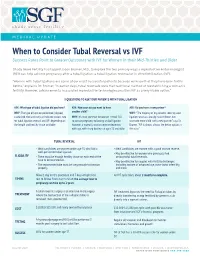

When to Consider Tubal Reversal Vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in Their Mid-Thirties and Older

MEDICAL UPDATE When to Consider Tubal Reversal vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in their Mid-Thirties and Older Shady Grove Fertility has tapped Jason Bromer, M.D., to explore the two primary ways a reproductive endocrinologist (REI) can help achieve pregnancy after a tubal ligation: a tubal ligation reversal or in vitro fertilization (IVF). "Women with tubal ligations are some of our most successful patients because we know that they have been fertile before," explains Dr. Bromer. "In earlier days, tubal reversals were the traditional method of reestablishing a woman’s fertility. However, advancements in assisted reproductive technologies position IVF as a very viable option." 3 QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR PATIENTS WITH TUBAL LIGATION ASK: What type of tubal ligation did you have? ASK: How soon do you want to have ASK: Do you have a new partner? WHY: The type of ligation performed (clipped, another child? WHY: "The majority of my patients seeking tubal cauterized, tied and cut) can indicate success rate WHY: It’s most common for women in their 30s ligation reversals already have children, but for tubal ligation reversal and IVF, depending on to pursue pregnancy following a tubal ligation. want one more child with a new partner," says Dr. the length and healthy tissue available. However, a woman’s ovarian reserve decreases Bromer. "IVF is almost always the better option in with age, with sharp declines at ages 35 and older. this case." TUBAL REVERSAL IVF • Ideal candidates are women under age 35 who had a • Ideal candidates are women with a good ovarian reserve. -

The Role of Endometrial Stem Cells in Recurrent Miscarriage

REPRODUCTIONREVIEW Success after failure: the role of endometrial stem cells in recurrent miscarriage Emma S Lucas1,2, Nigel P Dyer3, Katherine Fishwick1, Sascha Ott2,3 and Jan J Brosens1,2 1Division of Biomedical Sciences, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, UK, 2Tommy’s National Centre for Miscarriage Research, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry, UK and 3Warwick Systems Biology Centre, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Correspondence should be addressed to J Brosens; Email: [email protected] Abstract Endometrial stem-like cells, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and epithelial progenitor cells, are essential for cyclic regeneration of the endometrium following menstrual shedding. Emerging evidence indicates that endometrial MSCs (eMSCs) constitute a dynamic population of cells that enables the endometrium to adapt in response to a failed pregnancy. Recurrent miscarriage is associated with relative depletion of endometrial eMSCs, which not only curtails the intrinsic ability of the endometrium to adapt to reproductive failure but also compromises endometrial decidualization, an obligatory transformation process for embryo implantation. These novel findings should pave the way for more effective screening of women at risk of pregnancy failure before conception. Reproduction (2016) 152 R159–R166 Introduction Successful implantation of a human embryo is commonly date (Fragouli et al. 2013), each implanting blastocyst attributed to binary variables; i.e. nidation of a ‘normal’, is arguably unique. Furthermore, transient aneuploidy but not an ‘abnormal’, embryo in a ‘receptive’, but during development may not be unequivocally as not a ‘non-receptive’, endometrium is required for ‘bad’ as has been intuitively presumed because of the a successful pregnancy. -

27Th ANNUAL RESEARCH DAY & Henderson Lecture

27th ANNUAL RESEARCH DAY & Henderson Lecture FRIDAY, MAY 7, 2010 8:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Northrop Frye Hall, Ground Floor Victoria University, 73 Queen's Park Crescent East University of Toronto M5S 1K7 Lecturer: Jane Norman MD Professor of Maternal and Fetal Health, University of Edinburgh, UK Co-Director, Edinburgh Tommy’s Centre for Maternal and Fetal Health Research Topic: Being Born Too Soon – Do Obstetricians Have Anything To Offer? Abstract deadline: Friday, March 5, 2010 http://www.obgyn.utoronto.ca/Research/ResearchDay.htm For additional information or assistance, please contact Helen Robson at [email protected] PROGRAMME-AT-A-GLANCE (A.M.) Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 27th Annual Research Day, Friday, May 7, 2010 Northrop Frye Hall, Victoria University, University of Toronto, 73 Queen’s Park Crescent NF=Northrop Frye Hall Burwash Hall is located at the north end of the Victoria Quad 7:30 a.m. on Poster Set-up for Poster Session I [NF, ground floor, Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] 8:00 a.m. Registration & Continental Breakfast [NF, ground floor lobby] 8:25 – 8:30 a.m. Welcome: Dr. Alan Bocking, Chair [NF, ground floor Lecture Hall, Rm. 003] 8:30 – 9:45 a.m. Oral Session I (O1-O5) [NF, ground floor Lecture Hall, Rm. 003] 9:45 – 10:05 a.m. Coffee Break & Poster Session I Walkabout [NF, ground floor lobby; Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] 10:05 – 11:05 a.m. Poster Session I Tour [NF, Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] Groups A-F Poster Takedown for a.m. -

Sexual Assault Cover

Sexual Assault Victimization Across the Life Span A Clinical Guide G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc. St. Louis Sexual Assault Victimization Across the Life Span A Clinical Guide Angelo P. Giardino, MD, PhD Associate Chair – Pediatrics Associate Physician-in-Chief St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children Associate Professor in Pediatrics Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Elizabeth M. Datner, MD Assistant Professor University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Department of Emergency Medicine Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine in Pediatrics Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Janice B. Asher, MD Assistant Clinical Professor Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Pennsylvania Medical Center Director Women’s Health Division of Student Health Service University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc. St. Louis FOREWORD Sexual assault is broadly defined as unwanted sexual contact of any kind. Among the acts included are rape, incest, molestation, fondling or grabbing, and forced viewing of or involvement in pornography. Drug-facilitated behavior was recently added in response to the recognition that pharmacologic agents can be used to make the victim more malleable. When sexual activity occurs between a significantly older person and a child, it is referred to as molestation or child sexual abuse rather than sexual assault. In children, there is often a "grooming" period where the perpetrator gradually escalates the type of sexual contact with the child and often does not use the force implied in the term sexual assault. But it is assault, both physically and emotionally, whether the victim is a child, an adolescent, or an adult. The reported statistics are only an estimate of the problem’s scope, with the actual reporting rate a mere fraction of the true incidence. -

Annualreport 2010

AnnualReport 2010 Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward Memorial Hospital Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai Convocation Ceremony of Use of smart board by 1st MBBS students Fellowship and Certificate Courses Automated chappati maker Clean KEM campaign Cardiac Ambulance Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward Memorial Hospital Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Concept (Front & Back cover) Dr. Sanjay Oak Director -Medical Education and Major Hospitals Professor of Pediatric Surgery Publisher Diamond Jubilee Society Trust Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400 012. Printer Urvi Compugraphics A2/248, Shah & Nahar Industrial Estate, S.J. Marg, Lower Parel (West), Mumbai 400 013. Tel.: 91 - 22 - 2494 5863 © Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital, 2011 Acknowledgements Smt. Shraddha Jadhav Hon. Mayor Smt. Shailaja Girkar Shri Subodh Kumar Deputy Mayor Municipal Commissioner Shri Sunil Prabhu Smt. Manisha Patankar-Mhaiskar Leader of the House Additional Municipal Commissioner (Western Suburbs) Shri Rajhans Singh Shri Aseem Gupta Leader of the Opposition Additional Municipal Commissioner (Eastern Suburbs) Shri Rahul Shewale Shri Mohan Adtani Chairman-Standing Committee Additional Municipal Commissioner (City) Smt. Ashwini Mate Shri Rajeev Jalota Chairman-Public Health Committee Additional Municipal Commissioner (Projects) Shri Parshuram (Chotu) Desai Shri Rajendra Vale Chairman-Works Committee (City) Deputy Municipal Commissioner (Estate & General Administration) Shri Anil Pawar Shri Sanjay (Nana) Ambole Chairperson - Ward Committee Municipal Councillor From the Director’s desk..... The twin institutes of the Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital were established in 1926 with a nationalistic spirit to cater to the “health care needs of the northern parts of the island” to be manned entirely by Indians. -

Genetic Syndromes and Genes Involved

ndrom Sy es tic & e G n e e n G e f Connell et al., J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 2013, 4:2 T o Journal of Genetic Syndromes h l e a r n a DOI: 10.4172/2157-7412.1000127 r p u y o J & Gene Therapy ISSN: 2157-7412 Review Article Open Access Genetic Syndromes and Genes Involved in the Development of the Female Reproductive Tract: A Possible Role for Gene Therapy Connell MT1, Owen CM2 and Segars JH3* 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Truman Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 3Program in Reproductive and Adult Endocrinology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA Abstract Müllerian and vaginal anomalies are congenital malformations of the female reproductive tract resulting from alterations in the normal developmental pathway of the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, and vagina. The most common of the Müllerian anomalies affect the uterus and may adversely impact reproductive outcomes highlighting the importance of gaining understanding of the genetic mechanisms that govern normal and abnormal development of the female reproductive tract. Modern molecular genetics with study of knock out animal models as well as several genetic syndromes featuring abnormalities of the female reproductive tract have identified candidate genes significant to this developmental pathway. Further emphasizing the importance of understanding female reproductive tract development, recent evidence has demonstrated expression of embryologically significant genes in the endometrium of adult mice and humans. This recent work suggests that these genes not only play a role in the proper structural development of the female reproductive tract but also may persist in adults to regulate proper function of the endometrium of the uterus.