SLANT MAGAZINE 2013 25. Treme. David Simon and Eric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taylor Schilling "I'm Living My Dream Right Now," Said Taylor Schilling Share of Romantic Scenes

Art^IL IVING www.gsusignal.com/campuslife Top five moments of 2011-2012 In no particular order INTISAR SERAAJ Staff Writer le "Counseling Center Woes" 4i "Zeta Tau Alpha Sorority Inc., - April 2012 Under Investigation" Earlier this month it was revealed that the - February 2012 Counseling and Testing Center terminated the There were several articles this school year positions of nine clinical staff members, includ surrounding Greek organizations being inves ing six psychologists, on March 3, in addition tigated on the allegation of partaking in haz to its post-doctoral program being suspended. ing In this particular article, the sending of an The Counseling and Testing Center are deny anonymous letter to the Dean of Students was ing claims by the March 26 edition of Inside discussed, which sparked an investigation into Higher Ed that these staff members were elim the Delta Lambda chapter of the Zeta Tau Alpha inated due to retaliation for "their complaints sorority for hazing and other illegal practices. that some university policies involving the coun Follow up articles included reports of Greek- seling center had the potential to harm stu affiliated students trashing Signal papers in mas dents." Although the former staff members were sive amounts. prohibited from speaking from the media, the university spokesperson Andrea Jones stated that these positions were eliminated due to a 3* "Georgia State Accepts Sun Belt Reduction in Force process. Invitation" CHRIS SHATTUCK |THE SIGNAL -April 2012 Georgia State was thrust into 2011 's Occupy Atlanta movement The Sun Belt Conference offers the high 2* "Occupy Takedown" est division of collegiate football established -November 2011 Occupy GSU: they stormed classrooms to pass out This foil page list gave Georgia State students 10 by the National Collegiate Athletic Association Coverage of this movement was a must! flyers and chanted for their own causes. -

Paul Haggis's Televisual Oeuvre

Subverting Stereotypes from London, Ontario to Los Angeles, California: A Review and Analysis of Paul Haggis's Televisual Oeuvre Marsha Ann Tate ABD, Mass Communications Program College of Communications The Pennsylvania State University 115 Carnegie Building University Park, PA 16802 Email: [email protected] Last updated: June 3, 2005 @ 10:08 p.m. Paper presented at the 2005 Film Studies Association of Canada (FSAC) Conference, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Subverting Stereotypes from London, Ontario to Los Angeles, California -- M. A. Tate 2 Abstract Paul Haggis's recent forays into the feature film milieu have garnered the London, Ontario native widespread critical acclaim. Serving as a co-producer, director, and/or writer for a series of high- profile motion pictures such as Million Dollar Baby and Crash have propelled Haggis to Hollywood's coveted "A list" of directors and writers. Nonetheless, prior to his entrée into feature filmmaking, Mr. Haggis already enjoyed a highly distinguished career as a creator, producer, and writer in the North American television industry. A two-time Emmy Award recipient, Paul Haggis's television oeuvre encompasses an eclectic array of prime time sitcoms and dramas. Starting out as a writer for situation comedies such as Facts of Life and One Day at a Time, Mr. Haggis later moved on to created notable dramas including Due South, EZ Streets, and Family Law. Subversion of widely held stereotypes and showcasing society's myriad moral ambiguities are hallmarks of Haggis's dramatic endeavors in both television and feature films. While the two techniques have helped produce powerful and thought-provoking dramas, on occasion, they also have sparked controversies. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/25/12

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/25/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning Å Face/Nation Doodlebops Doodlebops College Basket. 2012 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Golf Digest Special Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Honda Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. (N) XTERRA World Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Doubt ››› (2008) 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Quest Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth Death, sacrifice and rebirth. Å 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Noticias Univision Santa Misa Desde Guanajuato, México. República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Misión S.O.S. Toonturama Presenta Karate Kid ›› (1984, Drama) Ralph Macchio. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Anney Perrine

ANNEY PERRINE Costume Designer www.anneyperrine .com YOUTH IN OREGON • Sundial Pictures • 2015 • Director: Joel David Moore • Producers: Joey Carey, Stefan Nowicki Cast: Frank Langella, Billy Crudup, Christina Applegate CUSTODY • Lucky Monkey Pictures • 2015 • Director: James Lapine • Producers: Katie Mustard, Lauren Versel Cast: Viola Davis, Ellen Burstyn, Hayden Panettiere, Catalina Moreno, Tony Shaloub, Dan Fogler THE PHENOM • Elephant Eye Films • 2014 • Director: Noah Buschel • Producers: Jeff Rice, Kim Jose, Aaron L. Gilbert Cast: Ethan Hawke, Paul Giamatti, Johnny Simmons, Sophie Kennedy Clark, Marin Ireland THE OUTSKIRTS • BCDF Pictures • 2014 • Director: Peter Hutchings • Producers: Brice Del Farra, Claude Del Farra Cast: Eden Sher, Victoria Justice, Peyton List, Ashley Rickards AD INEXPLORATA • Loveless • 2014 • Director: Mark Rosenberg • Producers: Josh Penn, Matthew Parker, Jason Berman Cast: Mark Strong, Sanaa Lathan, Luke Wilson BEFORE WE GO • G4 Productions • 2013 • Director: Chris Evans • Producers: McG, Mark Kassen, Mary Viola Cast: Chris Evans, Alice Eve, Emma Fitzpatrick *Special Presentation: Toronto International Film Festival 2014 ABOUT ALEX • Bedford Falls Co. • 2013 • Dir: Jesse Zwick • Prod: Edward Zwick, Marshall Herskovitz, Robyn Bennett, Adam Saunders Cast: Aubrey Plaza, Max Minghella, Nate Parker, Jason Ritter, Maggie Grace, Max Greenfield *Official Selection: Tribeca Film Festival 2014 MAHJONG AND THE WEST • BCDF Pictures & Apres Visuals • 2013 • Dir: Joseph Muszynski • Prod: Claude Dal Farra, Adam Piotrowicz Cast: Dominic Bogart, Tom Guiry, Louanne Stephens MEDAL OF VICTORY • Warehouse District Productions • 2013 • Director: Joshua Moise • Producer: Jason Schumacher Cast: Richard Riehle, Will Blomker COLD COMES THE NIGHT • Syncopated Films • 2012 • Dir: Tze Chun • Producers: Terry Leonard, Mynette Louie, Rick Rosenthal Cast: Bryan Cranston, Alice Eve, Logan Marshall-Green, Ursula Parker, Leo Fitzpatrick A BIRDER’S GUIDE TO EVERYTHING • Dreamfly Prod. -

4.5.1 Los Abducidos: El Duro Retorno En Expediente X Se Duda De Si Las

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB 4.5.1 Los abducidos: El duro retorno En Expediente X se duda de si las abducciones son obra de humanos o de extraterrestres por lo menos hasta el momento en que Mulder es abducido al final de la Temporada 7. La duda hace que el encuentro con otras personas que dicen haber sido abducidas siempre tenga relevancia para Mulder, Scully o ambos, como se puede ver con claridad en el caso de Cassandra Spender. Hasta que él mismo es abducido se da la paradójica situación de que quien cree en la posibilidad de la abducción es él mientras que Scully, abducida en la Temporada 2, siempre duda de quién la secuestró, convenciéndose de que los extraterrestres son responsables sólo cuando su compañero desaparece (y no necesariamente en referencia a su propio rapto). En cualquier caso poco importa en el fondo si el abducido ha sido víctima de sus congéneres humanos o de alienígenas porque en todos los casos él o ella cree –con la singular excepción de Scully– que sus raptores no son de este mundo. Como Leslie Jones nos recuerda, las historias de abducción de la vida real que han inspirado este aspecto de Expediente X “expresan una nueva creencia, tal vez un nuevo temor: a través de la experimentación sin emociones realizada por los alienígenas usando cuerpos humanos adquiridos por la fuerza, se demuestra que el hombre pertenece a la naturaleza, mientras que los extraterrestres habitan una especie de supercultura.” (Jones 94). -

Awards Ballot.Pages

Best Screenplay Best Motion Picture - Comedy or Musical Birdman Birdman Boyhood The Grand Budapest Hotel Gone Girl Into the Woods The Grand Budapest Hotel Pride The Imitation Game St. Vincent 2015 Golden Globes ! ! Best Animated Feature Film Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Big Hero 6 Picture - Drama FILM The Book of Life Jennifer Aniston, Cake Best Performance by an Actress The Boxtrolls Felicity Jones, The Theory of Everything in a Supporting Role How To Train Your Dragon 2 Julianne Moore, Still Alice Patricia Arquette, Boyhood The LEGO Movie Rosamund Pike, Gone Girl Jessica Chastain, A Most Violent Year ! Reese Witherspoon, Wild Keira Knightley, The Imitation Game ! Emma Stone, Birdman Best Director Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture - Meryl Streep, Into the Woods Wes Anderson, The Grand Budapest Hotel Drama Ava Duvernay, Selma ! Steve Carell, Foxcatcher David Fincher, Gone Girl Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, Birdman Picture - Comedy or Musical Jake Gyllenhaal, Nightcrawler Richard Linklater, Boyhood Amy Adams, Big Eyes David Oyelowo, Selma Emily Blunt, Into the Woods ! Eddie Redmayne, The Theory of Everything Helen Mirren, The Hundred-Foot Journey Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion ! Julianne Moore, Map to the Stars Picture - Comedy or Musical Best Motion Picture - Drama Quvenzhane Wallis, Annie Boyhood Ralph Fiennes, The Grand Budapest Hotel Foxcatcher ! Michael Keaton, Birdman The Imitation Game Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role Bill Murray, St. Vincent Selma Robert Duvall, The Judge Joaquin Phoenix, Inherent Vice The Theory of Everything Ethan Hawke, Boyhood Christoph Waltz, Big Eyes Edward Norton, Birdman ! Mark Ruffalo, Foxcatcher ! J.K. -

Odwołany Za Śmieci

Nr 11 Wprost pod 15 MARCA 2001 r. lokomotywę ISSN 1232-0366 7 X INDEKS: 328073 Cena: 2 ,0 0 zł owircl (w tym 7% VAT) NAJSTARSZE PISMO W REGIONIE. UKAZUJE SIĘ OD 1947 ROKU. Głuchołazy Zdenerwował się, bo obchodziła Dzień Kobiet Nieuwaga kierowcy fiata ducato sprawiła, że minio Luksusowy iż widział nadjeżdżający pociąg, wjechał nagle wprost pod koła lokomotywy. pustostan • czytaj n a str. 2 Mieszkanie o powierzchni po ZABIŁ nad 130 m kw. w centrum miasta od dwóch lat stoi puste i czeka na loka Mycie na granicy torów - rodzinę Szafrańskich z Jar nołtówka. • słr. 13 O tm uchów KONKUBINĘ W swoje gniazdo srasz? Nielegalna wycinka 10 drzew doprowadziła do konfliktu wśród mieszkańców Ligoty Wielkiej. Wieś podzieliła się na dwa obozy. Z Czech do Polski przechodzimy i • str. 11 przejeżdżamy przez roztwór sody Niem odlin kaustycznej • czytaj tia str. 5 Pomoc z Peine W N iem odlinie przebywała 11- osobowa grupa członków elitarne Odwołany go „Rotary Club” z zaprzyjaźnione go niemieckiego miasta Peine. • str. 14 za śmieci Paczków W ubiegły czwartek Zarząd Miejski w Nysie odwo łał Stanisława Ostrowskiego z funkcji prezesa należą cej do gminy spółki EKOM. Stan dobry, ale... Zdaniem Zarządu, w ostatnich miesiącach EKOM Targowisko w Paczkowie to jed W niedzielę sąd podjął decyzję o aresztowaniu sprawcy prowadził działania zmierzające do zawyżenia kosztów na wielka prowizorka, a oddalone o eksploatacji wysypiska w Domaszkowicach, a co się z niecałe 3 kilometry od miasta przej W czwartek 8 marca na ostatnim piętrze w jednym z nyskich bloków w Rynku 35-letni tym wiąże do nieuzasadnionego podniesienia cen wy ście graniczne nie spełnia norm sa pijany mężczyzna zakatował swoją konkubinę. -

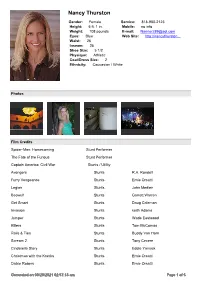

Nancy Thurston

Nancy Thurston Gender: Female Service: 818-980-2123 Height: 5 ft. 1 in. Mobile: no info Weight: 108 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Eyes: Blue Web Site: http://nancythurston... Waist: 26 Inseam: 26 Shoe Size: 5 1/2 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 2 Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Spider-Man: Homecoming Stunt Performer The Fate of the Furious Stunt Performer Captain America: Civil War Stunts / Utility Avengers Stunts R.A. Rondell Furry Vengeance Stunts Ernie Orsatti Legion Stunts John Medlen Beowulf Stunts Garrett Warren Get Smart Stunts Doug Coleman Invasion Stunts keith Adams Jumper Stunts Wade Eastwood Killers Stunts Tom McComas Rails & Ties Stunts Buddy Van Horn Scream 2 Stunts Tony Cecere Cinderella Story Stunts Eddie Yansick Christmas with the Kranks Stunts Ernie Orsatti Dickie Robers Stunts Ernie Orsatti Generated on 09/28/2021 02:57:18 am Page 1 of 5 Dan Bradely X-Files Stunts Bob Brown Swordfish Stunts Dan Bradley A.I. Stunts Doug Coleman The Dead Girl Stunts Darrin Prescott Charlie's Angels Stunts Armstrong Action / Vic and Andy Cahoots Stunts Matthew Taylor The Net Stunts Buddy Van Horn The Rock Stunts Kenny Bates Nemesis 2 Stunts Bob Brown Nemesis 3 Stunts Bob Brown Knights Stunts Bob Brown Sgt. Bilko Stunts Ernie Orsatti Stinkers Stunts Jeff Cadiente Blonde Justice Stunts Chuck Borden Summer Camp Stunts Jeff Dashnw The Sweeper Stunts Spiro Rozatos Up Close & Personal Stunts Doug Coleman George of the Jungle Stunts Phil Adams Mean Guns Stunts Jon Epstein Titanic Stunts Simon Crane Revenant Stunts Brett -

1 Nominations Announced for the 19Th Annual Screen Actors Guild

Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2013 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) LOS ANGELES (Dec. 12, 2012) — Nominees for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2012 in five film and eight primetime television categories as well as the SAG Awards honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA Executive Vice President Ned Vaughn introduced Busy Philipps (TBS’ “Cougar Town” and the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Social Media Ambassador) and Taye Diggs (“Private Practice”) who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Vice Chair Daryl Anderson and Committee Member Woody Schultz announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT at 10 p.m. (ET)/7 p.m. (PT). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the tntdrama.com and tbs.com live pre-show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET)/3 p.m. (PT). Of the top industry accolades presented to performers, only the Screen Actors Guild Awards® are selected solely by actors’ peers in SAG-AFTRA. -

Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland

This is a repository copy of “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150191/ Version: Published Version Article: Steenberg, L and Tasker, Y (2015) “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. Cinema Journal, 54 (4). pp. 132-138. ISSN 0009-7101 https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2015.0042 This article is protected by copyright. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cinema Journal 54 i No. 4 I Summer 2015 "Pledge Allegiance": Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and H o m e la n d by Lindsay Steenber g and Yvonne Tasker lthough there are numerous intertexts for the series, here we situate Homeland (Showtime, 2011—) in the generic context of American crime television. Homeland draws on and develops two of this genre’s most highly visible tropes: constant vigilance regardingA national borders (for which the phrase “homeland security” comes to serve as cultural shorthand) and the vital yet precariously placed female investigator.