UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mastodon's New Album Once More 'Round the Sun Debuts

For Immediate Release: MASTODON’S NEW ALBUM ONCE MORE ’ROUND THE SUN DEBUTS AT NO. 6 ON BILLBOARD CHART - THEIR HIGHEST U.S. CHART DEBUT EVER! THE NEW ALBUM IS ALSO TOP 20 AROUND THE WORLD ABC’S JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE CONFIRMED FOR SEPTEMBER 15TH July 2, 2014 — (Burbank, CA) — Once More ’Round The Sun, the sixth studio album from Mastodon, has debuted at No. 6 on the Billboard Top 200 Albums chart. This marks their highest chart debut ever. In addition, this album released by Reprise Records on June 24th, has gone Top 10 in most European markets and top 20 in most remaining territories. Once More ’Round The Sun has also entered the Top 10 Album Charts in the U.K. as well where it is currently the No. 1 Rock/Metal album across the nation; yet another milestone for Mastodon. Fans and critics agree, this is the best Mastodon album yet: “The mercurial metal heads have improved on the lean hard-rock pummel of 2011’s The Hunter with lattices of ornate riffs and primal vocals… the band sounds best when taking risks.” – Rolling Stone “Album after album, Mastodon set the pace for modern heavy metal. Their brand of aggression is brainy, technically dazzling and slightly hallucinogenic – metal for people who don’t usually listen to metal. At the same time, the band is balls-out creative. ‘Elegant’ isn’t a term usually associated with neck-tatted, acid-eating heshers but check out Bill Kelliher’s guitar riff verses Brent Hinds’ guitar solo versus Brann Dailor’s double-time drums. -

A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2020 A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde Zulema Denise Santana California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Recommended Citation Santana, Zulema Denise, "A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde" (2020). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 871. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/871 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde Global Studies Capstone Project Report Zulema D. Santana May 8th, 2020 California State University Monterey Bay 1 Introduction Religion has helped many immigrants establish themselves in their new surroundings in the United States (U.S.) and on their journey north from Mexico across the US-Mexican border (Vásquez and Knott 2014). They look to their God and then to their Mexican Folk Saints, such as La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde, for protection and strength. This case study focuses on how religion— in particular Folk Saints such as La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde— can give solace and hope to Mexican migrants, mostly Catholics, when they cross the border into the U.S, and also after they settle in the U.S. -

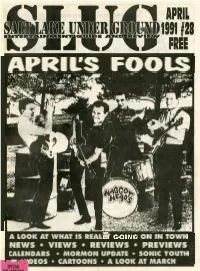

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

1Monologues' Conclude on Campus Farley Refurbishing Begins

r----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOLUME 40: ISSUE 89 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16.2006 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM 1Monologues' conclude on campus STUDENT SENATE Leaders Jenkins' attendance, broad panel discussion cap off third and final night of perfomances push wage "I went to listnn and learn, and By KAITLYNN RIELY I did that tonight and I thank the • Nrw.,Writ<·r east," Jenkins said af'tnr the play. .Jenkins, who dedinml further calllpaign Tlw third and final production comment on the "Monologues" of "Tiw Vagina Monologues" at Wednesday, had mandated the By MADDIE HANNA Notrn Damn this y11ar was play be pnrformed in the aca Associate News Editor marknd by thn attnndancn of demic setting of DeBartolo Hall Univnrsily Prnsid1n1l Father .John this year, without the l"undraising .Jnnkins and a wide-ranging ticket sales of' years past. Junior After loaders of the Campus parwl discussion on snxual vio Madison Liddy, director of this Labor Aetion Projoct (CLAP) lnHrn, Catholic. teaching and ynar's "Monologues." and later delivered a eornprnhnnsivo ollwr lopks Wednesday night. the panelists thanked Jenkins for presentation on the group's .11~11kins saw the play per his prnsenen at the performance . living wage campaign to l"orrm~d for tho f"irst time During tho panel diseussion fol Student Senate Wednesday, W1Hfrwsday, just ovnr three lowing thn play, panelists senators responded by unani w1wks after hP initialed a applauded the efforts of the pro mously passing two rolated Univnrsity-widn discussion about duction toward eliminating vio resolutions - one basod on acadnmk l"mmlom and Catholic lence against women and policy, tho other on ideology. -

The Current the Friendliest Club in Georgetown DECEMBER 2018

The Current The Friendliest Club in Georgetown DECEMBER 2018 Calendar of Events 1 LGA Awards Brunch 2 Diners Club Dinner 5 Gingerbread House Party 7 Berryville Christmas Party 8 MGA Breakfast Welcomes 8 Tennis Mixed Up Christmas Mixer DecemberNew Members 9 11 BCCCWA Holiday Dinner ALL DAY 13 BCCCMA Luncheon Spirits of Texas Tuesdays Wine & Whiskey 15 Breakfast with Santa Wednesdays Margarita & Mexican Martini 25 Merry Christmas! Thursdays Fired Up Fridays 29-30 Golf Junior Camp Satisfied Saturdays 31-4 Tennis Junior Camp Dec 7 December 15 6-9pm Breakfast with Santa Gingerbread House Party Golf December Golf Events Pro’s Corner 1 LGA Awards Brunch December 7th—Quit Putt-Zin Around Putting Clinic – 4pm to 5pm 7 Golf Shop Sale Pro Shop Sale- 6 pm to 9pm ( Pro Shop Will Be Closed from MGA Breakfast 8 4pm- 6pm to prepare) Jr. Golf Camp Looking for those last minute gifts? Maybe for yourself? 29-30 There will be a Keg of Beer in the shop to make your shopping experience a better one!!!! Golf Associations Reminder- December 31st all credit books get closed out so come check what you have in the pot and spend it. Tues 8:30 Sr. MGA Wed 8:30 LGA and 9 Holers, Junior Golf Camp Wed 12:30 MGA December 29th and 30th- 10am- 12pm Thurs All Day Golf Guest Day $25per junior Fri 1pm Skins/Quota Coming Soon January 1st Heaven and Hell 2 Person Battle 11am Shotgun SIGN UP IN THE $30 per member $40 for guests (Includes Lunch and Prizes) ACCOUNTING OFFICEInfo Front 9 is a Scramble - Pins in Center of the Greens and Heavenly Men White Tees and Ladies Red Tees -

Stand Up, Fight Back!

admin.iatse-intl.org/BulletinRegister.aspx Stand Up, Fight Back! The Stand Up, Fight Back campaign is a way for Help Support Candidates Who Stand With Us! the IATSE to stand up to attacks on our members from For our collective voice to be heard, IATSE’s members anti-worker politicians. The mission of the Stand Up, must become more involved in shaping the federal legisla- Fight Back campaign is to increase IATSE-PAC con- tive and administrative agenda. Our concerns and inter- tributions so that the IATSE can support those politi- ests must be heard and considered by federal lawmakers. cians who fight for working people and stand behind But labor unions (like corporations) cannot contribute the policies important to our membership, while to the campaigns of candidates for federal office. Most fighting politicians and policies that do not benefit our prominent labor organizations have established PAC’s members. which may make voluntary campaign contributions to The IATSE, along with every other union and guild federal candidates and seek contributions to the PAC from across the country, has come under attack. Everywhere from Wisconsin to Washington, DC, anti-worker poli- union members. To give you a voice in Washington, the ticians are trying to silence the voices of American IATSE has its own PAC, the IATSE Political Action Com- workers by taking away their collective bargaining mittee (“IATSE-PAC”), a federal political action commit- rights, stripping their healthcare coverage, and doing tee designed to support candidates for federal office who away with defined pension plans. promote the interests of working men and women. -

Popular Religion and Festivals

12 Popular Religion and Festivals The introduction of Roman Catholicism to the New World was part of the colonizing policy of both the Spanish and the Portuguese, but on Latin American soil Christian beliefs and practices came into contact with those of the native Amerindian peoples, and later with those brought by enslaved Africans and their descendants. Latin American Catholicism has consequently absorbed elements of pre-Columbian reli- gious beliefs and practices, giving rise to what is known as “popular” or “folk” Catholicism. Popular Catholicism has blended elements of differ- ent religions, yet it is still a recognizable mutation of traditional Roman Catholicism. In Mexico, for example, Catholic saints are matched up with pre-Columbian deities, as are Christian festivals with indigenous ones. Similarly, popular religion in the Andean countries must be under- stood in its historical and cultural context, since it is heavily influenced by the experience of conquest and the persistence of indigenous beliefs under a Christian guise. In recent years, Catholicism in Latin America has also become synony- mous with Liberation Theology, with its commitment to social change and improvement of the lot of marginal sectors. This radical theology was announced at Medellín, Colombia, in 1968 with a formal declaration of the Church’s identification with the poor. The doctrine’s complexity and diversity make it difficult to define, but the influence of Marxism is apparent, along with that of pioneering social reformers and educators such as the Brazilian Paulo Freire. Liberation Theology’s most famous advocate is the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, whose humble origins sharpened his awareness of social problems. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

FAULT LINES Ridgites: Sidewalks Are City’S Newest Cash Cow by Jotham Sederstrom the Past Two Months; 30 Since the Beginning of the Brooklyn Papers the Year

I N S BROOKLYN’S ONLY COMPLETE U W L • ‘Bollywood’ comes to BAM O P N • Reviewer gives Park Slope’s new Red Cafe the green light Nightlife Guide • Brooklyn’s essential gift guide CHOOSE FROM 40 VENUES — MORE THAN 140 EVENTS! 2003 NATIONAL AWARD WINNER Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications at 26 Court St., Brooklyn, NY 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 © Brooklyn Paper Publications • 14 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol.26, No. 49 BRZ • December 8, 2003 • FREE FAULT LINES Ridgites: Sidewalks are city’s newest cash cow By Jotham Sederstrom the past two months; 30 since the beginning of The Brooklyn Papers the year. If you didn’t know better, you’d think “To me, it seems like an extortion plot,” said that some of the homeowners along a par- Tom Healy, who lives on the block with his ticular stretch of 88th Street were a little wife, Antoinette. Healy received a notice of vio- strange. lation on Oct. 24. / Ramin Talaie “It’s like if I walked up to your house and For one, they don’t walk the sidewalks so said, ‘Hey, you got a crack, and if you don’t fix much as inspect them, as if each concrete slab between Third Avenue and Ridge Boulevard it were gonna do it ourselves, and we’re gonna bring our men over and charge you.’ If it was were a television screen broadcasting a particu- Associated Press larly puzzling rerun of “Unsolved Mysteries.” sent by anyone other than the city, it would’ve But the mystery they’re trying to solve isn’t been extortion,” he said. -

C 1992-219 a Nahuatl Interpretation of the Conquest

In: Amaryll Chanady, Latin American Identity and Constructions of Difference, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Vol. 10, 1994, pp. 104-129. Chapter 6 A Nahuatl Interpretation of the Conquest: From the "Parousia" of the Gods to the "Invasion" Enrique Dussel (translated by Amaryll Chanady) In teteu inan in tetu ita, in Huehueteutl [Mother of the gods, Father of the gods, the Old God], lying on the navel of the Earth, enclosed in a refuge of turquoises. He who lives in the waters the color of a blue bird, he who is surrounded by clouds, the Old God, he who lives in the shadows of the realm of the dead, the lord of fire and time. -Song to Ometeótl, the originary being of the Aztec Tlamatinime1 I would like to examine the "meaning of 1492," which is nothing else but "the first experience of modem Europeans," from the perspective of the "world" of the Aztecs, as the conquest in the literal sense of the term started in Mexico. In some cases I will refer to other cultures in order to suggest additional interpreta- tions, although I am aware that these are only a few of the many possible examples, and that they are a mere "indication" of the problematic. Also, in the desire to continue an intercultural dia- logue initiated in Freiburg with Karl-Otto Apel in 1989, I will re- fer primarily to the existence of reflexive abstract thought on our continent.2 The tlamatini In nomadic societies (of the first level) or societies of rural plant- ers (like the Guaranis), social differentiation was not developed sufficiently to identify a function akin to that of the "philoso- pher", although in urban society this social figure acquires a dis- tinct profile.3 As we can read in Garcilaso de la Vega's Comenta- rios reales de los Incas: 104 105 Demás de adorar al Sol por dios visible, a quien ofrecieron sacrificios e hicieron grandes fiestas,.. -

Magnitude and Frequency of Heat and Cold Waves in Recent Table 1

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 3, 7379–7409, 2015 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/3/7379/2015/ doi:10.5194/nhessd-3-7379-2015 NHESSD © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 3, 7379–7409, 2015 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Natural Hazards and Earth Magnitude and System Sciences (NHESS). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in NHESS if available. frequency of heat and cold waves in recent Magnitude and frequency of heat and cold decades: the case of South America waves in recent decades: the case of G. Ceccherini et al. South America G. Ceccherini1, S. Russo1, I. Ameztoy1, C. P. Romero2, and C. Carmona-Moreno1 Title Page Abstract Introduction 1DG Joint Research Centre, European Commission, Ispra 21027, Italy 2 Facultad de Ingeniería Ambiental, Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogota 5878797, Colombia Conclusions References Received: 12 November 2015 – Accepted: 23 November 2015 – Published: Tables Figures 10 December 2015 Correspondence to: G. Ceccherini ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 7379 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract NHESSD In recent decades there has been an increase in magnitude and occurrence of heat waves and a decrease of cold waves which are possibly related to the anthropogenic 3, 7379–7409, 2015 influence (Solomon et al., 2007). This study describes the extreme temperature regime 5 of heat waves and cold waves across South America over recent years (1980–2014). -

A Holy Nation: Bible Study the Fifth Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church

A Holy Nation: Bible Study The Fifth Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church Year Three - Pentecost Rev. Francine A. Brookins, Esq. and Rev. Jennifer S. Leath, Ph.D., Editors 1st Edition Introduction to a Holy Nation: Bible Study ........9 Contributors ....................................................................................................................10 An Holy, Loving, and “Democratic” Spirit: What Pentecost Reveals about God .............................11 Rev. M. JoDavid Sales, Ph.D. Pastor, Bethel AMEC (Marysville, CA) Go and Make Students: Holistic or Emaciated Evangelism .........................................................14 Rev. M. JoDavid Sales, Ph. D. Pastor, Bethel AMEC (Marysville, CA) Amazing Grace ...................................................17 Mrs. Mary Mayo Mayberry President, 5th Episcopal District Women’s Missionary Society Your Kingdom Come .........................................20 Rev. Mary S. Minor, D. Min. Pastor, Brookins-Kirkland Community AMEC (Los Angeles, CA) Come, Holy Spirit ..............................................22 Ms. Pamela Williams President, Missouri Conference Lay Organization Who Do We Say We Are? ..................................24 Rev. Mark Whitlock, Jr., M.Div., MSSE Pastor, Christ Our Redeemer AMEC (Irvine, CA) !2 Experiencing Spiritual Renewal: Take Off The Masks! ................................................................26 Rev. Mark Whitlock, Jr., M.Div., MSSE Pastor, Christ Our Redeemer AMEC (Irvine, CA) Pregnant With Praise ........................................28