Grammatical Number and the Scale of Individuation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

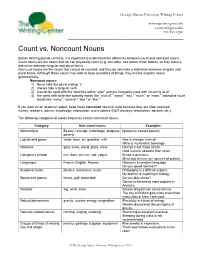

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Introduction to Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles: ALAOTSIKKO

1 Introduction to Case, animacy and semantic roles Please cite this paper as: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi and Jussi Ylikoski. (2011) Introduction to case, animacy and semantic roles. In: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi & Jussi Ylikoski (Eds.), Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles, 1-26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Seppo Kittilä Katja Västi Jussi Ylikoski University of Helsinki University of Oulu University of Helsinki University of Helsinki 1. Introduction Case, animacy and semantic roles and different combinations thereof have been the topic of numerous studies in linguistics (see e.g. Næss 2003; Kittilä 2008; de Hoop & de Swart 2008 among numerous others). The current volume adds to this list. The focus of the chapters in this volume lies on the effects that animacy has on the use and interpretation of cases and semantic roles. Each of the three concepts discussed in this volume can also be seen as somewhat problematic and not always easy to define. First, as noted by Butt (2006: 1), we still have not reached a full consensus on what case is and how it differs, for example, from 2 the closely related concept of adpositions. Second, animacy, as the label is used in linguistics, does not fully correspond to a layperson’s concept of animacy, which is probably rather biology-based (see e.g. Yamamoto 1999 for a discussion of the concept of animacy). The label can therefore, if desired, be seen as a misnomer. Lastly, semantic roles can be considered one of the most notorious labels in linguistics, as has been recently discussed by Newmeyer (2010). There is still no full consensus on how the concept of semantic roles is best defined and what would be the correct or necessary number of semantic roles necessary for a full description of languages. -

Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 39.1 (June 2017): 33-54 issn 0210-6124 | e-issn 1989-6840 Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants Yolanda Fernández-Pena Universidade de Vigo [email protected] This corpus-based study investigates the patterns of verbal agreement of twenty-three singular collective nouns which take of-dependents (e.g., a group of boys, a set of points). The main goal is to explore the influence exerted by theof -PP on verb number. To this end, syntactic factors, such as the plural morphology of the oblique noun (i.e., the noun in the of- PP) and syntactic distance, as well as semantic issues, such as the animacy or humanness of the oblique noun within the of-PP, were analysed. The data show the strongly conditioning effect of plural of-dependents on the number of the verb: they favour a significant proportion of plural verbal forms. This preference for plural verbal patterns, however, diminishes considerably with increasing syntactic distance when the of-PP contains a non-overtly- marked plural noun such as people. The results for the semantic issues explored here indicate that animacy and humanness are also relevant factors as regards the high rate of plural agreement observed in these constructions. Keywords: agreement; collective; of-PP; distance; animacy; corpus . Concordancia verbal con construcciones nominales colectivas: sintaxis y semántica como factores determinantes Este estudio de corpus investiga los patrones de concordancia verbal de veintitrés nombres colectivos singulares que toman complementos seleccionados por la preposición of, como en los ejemplos a group of boys, a set of points. -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY of ENGLISH USE in COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROW’S MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 i MOTTO “EDUCATION IS WHAT REMAINS AFTER ONE HAS FORGOTTEN WHAT ONE HAS LEARNED IN SCHOOL.” (Albert Eistein) “EDUCATION IS A PROGRESSIVE DISCOVERY OF OUR OWN IGNORENCE.” (Charlie Chaplin) “EVERY THE LAST STEP INEVITABLY HAS THE FIRST STEP” (Muji Retno) ii ACKNOWLEDGE All praises to Allah who has blessed, guided and given the health to the researcherduring writing this thesis. Then, the researcherr would like to send invocation and peace to Prophet Muhammad SAW peace be upon him, who has guided the people from the bad condition to the better life. The researcher realizes that in writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people that have provided their suggestion, advice, help and motivation. Therefore, the researcher would like to express thanks and highest appreciation to all of them. For the first, the researcher gives special gratitude to her parents, Masir Hadis and Jumariah Yaha who have given their loves, cares, supports and prayers in every single time.