Television Production in Post-Network Era: Changing Strategies of CBS, HBO, and Netflix an Analysis on the Big Bang Theory, Game of Thrones, and Sense 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX

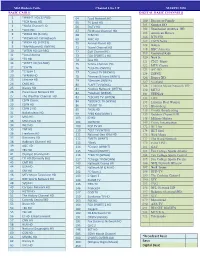

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX TV SERVICES BASIC TV 2 Univision HD 12 KZTV CBS HD 22 Azteca America 192 TBN HD CHANNELS 816 CW-HD 3 Local Weather 13 KDF Independent 23 HSN HD 193 Inspiration Network 802 Univision HD 817 Telemundo HD 4 QVC HD 14 Retro TV 96 C-SPAN 270 Charge! 804 QVC HD 823 HSN HD 5 KIII ABC HD 15 My Network TV 137 QVC Plus 280 Grit 805 KIII ABC HD 7 KRIS NBC HD 16 CW 138 HSN 2 281 MeTV 807 KRIS NBC HD 8 UniMás 17 Telemundo HD 139 Jewelry TV 282 ION 809 KEDT PBS HD MUSIC CHOICE 9 KEDT PBS HD 18 Public Access 173 PBS Create 283 Create 811 KUQI FOX HD 701-752 10 Public Access 19 Educational Access 190 Daystar 284 Cozi TV 812 KZTV CBS HD 11 KUQI FOX HD 20 City of Corpus Christi 191 EWTN 291 UniMás 292 LATV PREFERRED TV (includes Basic TV) 1 On Demand 46 MSNBC HD 69 Oxygen HD 246 IndiePlex 841 Weather Channel HD 865 Bravo HD 6 NewsNation HD 47 truTV HD 70 History Channel HD 247 RetroPlex 842 CNN HD 866 Galavision HD 24 TNT HD 48 OWN HD 71 Travel Channel HD 393 HBO** 843 HLN HD 867 Syfy HD 25 TBS HD 49 TV Land HD 72 HGTV HD 397 Amazon Prime** 844 Fox News HD 868 Comedy Central HD 26 USA HD 50 Discovery HD 73 Food Network HD 398 HULU** 845 CNBC HD 869 Oxygen HD 27 A&E HD 51 TLC HD 77 SEC Network HD 399 NETFLIX** 846 MSNBC HD 870 History Channel HD 28 Lifetime HD 52 Animal Planet HD 78 SEC Network - Alternative HD CHANNELS 847 truTV HD 871 Travel Channel HD 29 E! HD 53 Freeform HD 79 Fox Sports 2 HD 806 NewsNation HD 848 OWN HD 872 HGTV HD 54 Hallmark Channel HD 30 Paramount Network HD 82 Tennis Channel 824 TNT HD 849 TV Land -

Photograph by Candace Dicarlo

60 MAY | JUNE 2013 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE PHOTOGRAPH BY CANDACE DICARLO Showtime CEO Matt Blank has used boundary-pushing programming, cutting-edge marketing, and smart management to build his cable network into a national powerhouse. By Susan Karlin SUBVERSIVE PRACTICALLY PRACTICALLY THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2013 61 seems too … normal. “Matt runs the company in a very col- Showtime, Blank is involved with numer- This slim, understated, affa- legial way—he sets a tone among top man- ous media and non-profit organizations, Heble man speaking in tight, agers of cooperation, congeniality, and serving on the directing boards of the corporate phrases—monetizing the brand, loose boundaries that really works in a National Cable Television Association high-impact environments—this can’t be creative business,” says David Nevins, and The Cable Center, an industry edu- the guy whose whimsical vision has Showtime’s president of entertainment. cational arm. Then there are the frequent turned Weeds’ pot-dealing suburban “It helps create a sense of, ‘That’s a club trips to Los Angeles. mom, Dexter’s vigilante serial killer, and that I want to belong to.’ He stays focused “I’m an active person,” he adds. “I like Homeland’s bipolar CIA agent into TV on the big picture, maintaining the integ- a long day with a lot of different things heroes. Can it? rity of the brand and growing its exposure. going on. I think if I sat in a room and did Yet Matt Blank W’72, the CEO of Showtime, Matt is very savvy at this combination of one thing all day, I’d get frustrated.” has more in common with his network than programming and marketing that keeps his conventional appearance suggests. -

Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD by Steve Sternberg

April 2021 #105 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD By Steve Sternberg Last year’s upfront season was different from any I’ve been involved in during my 40 years in the business. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were no live network presentations to the industry, and for the first time since I’ve been evaluating television programming, I did not watch any of the fall pilots before the shows aired. Many new and returning series experienced production delays, resulting in staggered premieres, shortened seasons, and unexpected cancellations. The big San Diego and New York comic-cons were canceled. There was virtually no pre-season buzz for new broadcast or cable series. Stuck at home with fewer new episodes of scripted series than ever to watch on ad-supported TV, people turned to streaming services in large numbers. Netflix, which had plenty of shows in the pipeline, surged in terms of both viewers and new subscribers. Disney+, boosted by season 2 of The Mandalorian and new Marvel series, WandaVision and Falcon and the Winter Soldier, was able to experience tremendous growth. A Sternberg Report Sponsored Message The Sternberg Report ©2021 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu also managed to substantially grow their subscriber bases. Warner Bros. announcing it would release all of its movies in 2021 simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max (led by Wonder Woman 1984 and Godzilla vs. Kong), helped add subscribers to that streaming platform as well – as did its successful original series, The Flight Attendant. CBS All Access, rebranded as Paramount+, also enjoyed growth. -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

From Broadcast to Broadband: the Effects of Legal Digital Distribution

From Broadcast to Broadband: The Effects of Legal Digital Distribution on a TV Show’s Viewership by Steven D. Rosenberg An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2007 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Jarl G. Kallberg Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Legal Digital Distribution............................................................................................. 6 2.1 iTunes ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Streaming ................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Current thoughts ...................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Financial importance ............................................................................................. 12 3. Data Collection ............................................................................................................ 13 3.1 Ratings data ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Repeat data ............................................................................................................ -

Summit Guide Guide Du Sommet Guía De La Cumbre Contents/Sommaire/Sumario

New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace 9-10 June 2009 – Ronald Reagan Center – Washington DC, USA www.copyrightsummit.com Summit Guide Guide du Sommet Guía de la Cumbre Contents/Sommaire/Sumario Page Welcome 1 Conference Programme 3 What’s happening around the Summit? 11 Additional Summit Information 12 Page Bienvenue 14 Programme des conférences 15 Autres événements autour du sommet ? 24 Informations supplémentaires du sommet 25 Página Bienvenidos 27 Programa de las Conferencias 28 ¿Lo que pasa alrededor del conferencia? 38 Información sobre el conferencia 39 Page Sponsor & Advisory Committee Profiles 41 Partner Organization Profiles 44 Media Partner Profiles 49 Speaker Biographies 53 9-10 June 2009 – Ronald Reagan Center – Washington DC, USA New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace Welcome Welcome to the World Copyright Summit! Two years on from our hugely successful inaugural event in Brussels it gives me great pleasure to welcome you all to the 2009 World Copyright Summit in Washington, DC. This year’s slogan for the Summit – “New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace” – illustrates perfectly what we aim to achieve here: remind to the world that creators’ contributions are fundamental for cultural, economic and social development but also that creators – and those who represent them – face several daunting challenges in this new digital economy. It is imperative that we bring to the forefront of political debate the creative industries’ future and where we, creators, fit into this new landscape. For this reason we have gathered, under the CISAC umbrella, all the stakeholders involved one way or another in the creation, production and dissemination of creative works. -

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television

temp Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television A production of the Console- ing Passions book series Edited by Lynn Spigel Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Warnock and News Gothic by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Restivo, Angelo, [date] author. Title: Breaking bad and cinematic television / Angelo Restivo. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Spin offs : a production of the Console-ing Passions book series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018033898 (print) LCCN 2018043471 (ebook) ISBN 9781478003441 (ebook) ISBN 9781478001935 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478003083 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Breaking bad (Television program : 2008–2013) | Television series— Social aspects—United States. | Television series—United States—History and criticism. | Popular culture—United States—History—21st century. Classification: LCC PN1992.77.B74 (ebook) | LCC PN1992.77.B74 R47 2019 (print) | DDC 791.45/72—dc23 LC record available at https: // lccn.loc.gov/2018033898 Cover art: Breaking Bad, episode 103 (2008). Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Georgia State University’s College of the Arts, School of Film, Media, and Theatre, and Creative Media Industries Institute, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Not to mention that most terrible drug—ourselves— which we take in solitude. —WALTER BENJAMIN Contents note to the reader ix acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 The Cinematic 25 2 The House 54 3 The Puzzle 81 4 Just Gaming 116 5 Immanence: A Life 137 notes 159 bibliography 171 index 179 Note to the Reader While this is an academic study, I have tried to write the book in such a way that it will be accessible to the generally educated reader. -

Television Content Quality and Engagement

GONZÁLEZ, M., RONCALLO-DOW, S., ARANGO-FORERO, G. Y URIBE-JONGBLOED, E. Television content quality and engagement CUADERNOS.INFO Nº 37 ISSN 0719-3661 Versión electrónica: ISSN 0719-367x http://www.cuadernos.info doi: 10.7764/cdi.37.812 Received: 08-06-2015 / Accepted: 11-04-2015 Television content quality and engagement: Analysis of a private channel in Colombia1 Calidad en contenidos televisivos y engagement: Análisis de un canal privado en Colombia Qualidade de conteúdos televisivos e engagement: Análise de um canal privado na Colômbia MANUEL IGNACIO GONZÁLEZ BERNAL2, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] SERGIO RONCALLO-DOW, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] GERMÁN ARANGO-FORERO, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] ENRIQUE URIBE-JONGBLOED, Departamento de Comunicación Social, Universidad del Norte. Barranquilla, Colombia [[email protected]] ABSTRACT RESUMEN RESUMO This paper presents the results of a Este artículo expone los resultados de Este artigo expõe os resultados de content analysis and an inquiry into un proyecto de investigación enfocado en um projeto de pesquisa enfocado em Colombian audiences regarding the comprender los elementos que intervienen compreender os elementos que intervêm concept of ‘quality television’ and its en la generación de engagement por parte na geração de engagement por parte effect upon engagement. The results de los televidentes colombianos y el aporte dos telespectadores colombianos e a show that for the sampled audience del concepto de ‘calidad televisiva’ a ese contribuição do conceito de ‘qualidade the most relevant elements in terms of proceso. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

First Media Partners with HBO GO to Offer Unlimited Access to All Available Content on HBO with One Subscription

PRESS RELEASE First Media partners with HBO GO to Offer Unlimited Access to All Available Content on HBO with One Subscription Jakarta, May 16th 2018 – First Media, a leader and pioneer in the cable TV industry and broadband Internet in Indonesia, presents HBO GO, an Internet-based service from HBO to bring the best mobile experience. HBO GO allows First Media customers to enjoy exclusive entertainment from HBO Originals: HBO series, HBO movies, documentaries, as well as Hollywood blockbusters through various devices (computers, tablets and smartphones). HBO GO is available for download from both the Google Play and the App Store, or visit the website at www.hbogoasia.com. "We are very excited to be the first partner in Indonesia to launch HBO GO on First Media. Aside from offering a vast array of premium channels, it is also our commitment to our subscribers to offer the best entertainment on the go (to be viewed anywhere and anytime) which includes the best of HBO Originals: HBO series, HBO movies, documentaries, as well as Hollywood blockbusters,” said Meena Kumari Adnani, Executive Vice President of Content Development and Business Affairs at First Media. Based on SVOD Report Statista 2018 the penetration of users Streaming video on demand (SVOD) accessed through the internet in Indonesia in 2018 reached 3.7% and is predicted to reach 7.9% by 2022. Internet access from mobile device users, by 2017, 28.78% of the population accesses the internet via mobile devices and is expected to reach 38.22% by 2021 (Mobile internet Statista 2017). This shows the growing trend of accessing internet video content via mobile.