Matter 3 Hearing Statement on Behalf of the Fairfield Partnership (1140352)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Patchway Town Centre Council Draft Profile Updated to June 2014 Policies, Sites & Places Plan Please send any further suggestions for Draft Town Centre Profiles change to [email protected] This is one of a series of draft town centre profiles which will be used to inform future planning policy. Initial comments were invited to arrive by 31st December 2013. Comments were made by: Patchway Town Council on behalf of the Patchway Town Centre Group which has representatives of several local interest groups. Patchway District Centre 1. Location The original shopping parade of M5 Junction 16 Rodway Road is located north of Highwood Road. A new local centre to serve Charlton Hayes is developing Coniston south of Highwood Road. Parade The intention is to consolidate both areas to become a Rodway Road recognisable town centre. Local Centre Patchway also has local centres at Coniston Road and along the A38. Highwood Road 2. Origin Patchway Roundabout The older area of Rodway local shops Road was developed as a suburban shopping parade in the 1930s. There was some A38 local further expansion in the 1950s shops Proposed Charlton and redevelopment of the Hayes Local Centre library in 2010 to form a new locality hub offering a range of services. The new local centre at Charlton Hayes is, at 2014, still Patchway – Existing and proposed local centres. under development to serve the new neighbourhood of over The aim is to combine the existing and proposed 2,000 dwellings. However there Rodway Road and Charlton Hayes local centres to is a real opportunity to fulfil the form a new town/district centre to serve the vision of Patchway Town established and new communities across Highwood Council for an integrated town Road. -

Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes

Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes Contents Sketch map 208 Key characteristics 209 Location 210 Physical influences 210 Land cover 210 Settlement and infrastructure 212 Landscape character 214 The changing landscape 217 Landscape strategy 220 Photographs Landscape character area boundary www.southglos.gov.uk 207 Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes •1 â2 è18 •3 •19 •15 •21•16 å13 á14 •17 •7 å8 æ9 â13 å14 ç15 •10 •11 ã12 Figure 46 Patchway, Filton Key å15 Photograph viewpoints and the Stokes \\\ Core strategy proposed new neighbourhood Sketch Map Scale: not to scale 208 www.southglos.gov.uk Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes The Patchway, Filton and the Stokes character area is an urban built up area, consisting of a mix of residential, N commercial and retail development and major transport corridors, with open space scattered throughout. Key Characteristics ¡ This area includes the settlements of ¡ Open space is diverse, currently including Patchway and Filton plus Bradley Stoke, areas of Filton Airfield much of which is Stoke Gifford, Harry Stoke and Stoke Park. proposed for development, as well as within the railway junction, the courses ¡ Largely built up area, bounded by of Patchway Brook and Stoke Brook, motorways to the north west and north part of historic Stoke Park and remnant east, with railway lines and roads dividing agricultural land. -

Outline Business Case

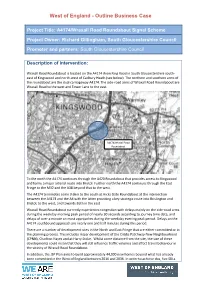

West of England - Outline Business Case Project Title: A4174/Wraxall Road Roundabout Signal Scheme Project Owner: Richard Gillingham, South Gloucestershire Council Promoter and partners: South Gloucestershire Council Description of Intervention: Wraxall Road Roundabout is located on the A4174 Avon Ring Road in South Gloucestershire south- east of Kingswood and north-west of Cadbury Heath (see below). The northern and southern arms of the roundabout are the dual carriageway A4174. The side-road arms of Wraxall Road Roundabout are Wraxall Road to the west and Tower Lane to the east. A4174/Wraxall Road Roundabout To the north the A4174 continues through the A420 Roundabout that provides access to Kingswood and forms a major arterial route into Bristol. Further north the A4174 continues through the East Fringe to the M32 and the A38 beyond that to the west. The A4174 terminates some 3.6km to the south at Hicks Gate Roundabout at the intersection between the A4174 and the A4 with the latter providing a key strategic route into Brislington and Bristol, to the west, and towards Bath in the east. Wraxall Road Roundabout currently experiences congestion with delays mainly on the side-road arms during the weekday morning peak period of nearly 30 seconds according to journey time data, and delays of over a minute on most approaches during the weekday evening peak period. Delays on the A4174 southbound approach are nearly one and half minutes during this period. There are a number of development sites in the North and East Fringe that are either committed or in the planning process. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED and NOTICE of POLL Date of Election: Thursday 6 May 2021

South Gloucestershire Council STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED AND NOTICE OF POLL Date of Election: Thursday 6 May 2021 1. Polling will take place between the hours of 7:00 am to 10:00 pm on Thursday 6 May 2021, for the election of Town Councillors for each of the undermentioned town wards, there remaining in each case more validly nominated candidates than seats. 2. The name, description (if any) and address of each candidates, together with the names of proposer, seconder and assentors are shown below for each electoral area. 3. Any candidate who an entry in the last column (invalid), in no longer standing at this election 4. Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of a Police and Crime Commissioner for Avon and Somerset Police Area and the election of a Mayor for the West of England Combined Authority Bradley Stoke Town Council, North Ward (Election for ONE Councillor) Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer Invalid MOREY 156 Dewfalls Drive, Bradley Stoke, BS32 Hanning Katie, Gibson Christine P Angela 9BU NTEKOR 15 Foxfield Avenue, Bradley Stoke, Bristol, Conservative Party Candidate Ntekor Eric B, Markey Gifty Eugenia BS32 0BN OLIVER (address in South Gloucestershire) Labour Party Fazzino Fabrizio, Di Domenico Paola Anthony Babatunde Bradley Stoke Town Council, South Ward (Election for ONE Councillor) Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer Invalid HE 34 The Worthys, Bradley Stoke, Bristol, Conservative Party Candidate Tregarthen Richard C, Tregarthen Elizabeth -

OCTOBER 2013 To: 31 OCTOBER 2013

South Gloucestershire Council MONTHLY LIST OF DECISIONS BY PARISH From: 01 OCTOBER 2013 To: 31 OCTOBER 2013 Monthly List of Decisions - 01/10/2013 - 31/10/2013 APPLICATION NUMBER APPLICATION TYPE LOCATION PROPOSAL APPLICANT DATE REGISTERED DECISION DATE DECISION PARISH Almondsbury Parish Council PT13/3301/FFull Planning 1 And 2 The Dinky Main Road Change of use of ground floor Mr Terry 10/09/2013 18/10/2013 Withdrawn Easter Compton South from Retail (Class A1) to 1no. self- Whittingham Gloucestershire BS35 5SJ contained flat (Class C3) as defined in Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987 (as amended). PT13/3004/RVCRemoval Var Con Unit 12A Cribbs Retail Park Removal of Condition 2 attached Cribbs Mall 14/08/2013 21/10/2013 Refusal Sec 73 Lysander Road Patchway South to PT13/1156/F re: the removal of Nominees (1) And Gloucestershire BS34 5UQ the need to provide a landscaping Cribbs Mall scheme Nominees (2) Ltd PT13/3821/FFull Planning 9 Florence Park Almondsbury Demolition of existing Mr And Mrs Martin 22/10/2013 Permitted Bristol South Gloucestershire BS32 conservatory to facilitate the Development 4HE erection of a single storey rear extension to provide additional living accommodation PT13/3380/FFull Planning Unit 13A The Venue Cribbs Creation of an external seating Nando's 17/09/2013 23/10/2013 Approve with Causeway Bristol South area with associated works. Chickenland Ltd Conditions Gloucestershire BS10 7SR PT13/3081/FFull Planning DHL International (UK) Ltd Erection of shed for a temporary D H L 28/08/2013 17/10/2013 Withdrawn Lysander Road Westbury On Trym period of two years for the storage International (UK) Bristol South Gloucestershire BS10 of pallets Ltd 7DD PT13/2146/FFull Planning Land At Catbrain Lane Erection of amenity PMH Western Ltd 25/06/2013 31/10/2013 Approved - S106 Almondsbury Bristol South Restaurant/Public House (Class Signed Gloucestershire BS10 7TQ A3/A4) with ancillary first floor staff accommodation and access, parking, landscaping and associated works. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan (March 2014)

South Gloucestershire Infrastructure Delivery Plan March 2014 Infrastructure Delivery Statement – Supporting Explanation Planning for infrastructure to meet existing deficiencies and future growth is a high priority for the Council. It therefore continues to work closely with its development partners, the West of England Partnership (4UAs) and other statutory and non-statutory organisations to identify and bring forward new and improve existing infrastructure. The information shown in the following matrix reflects the current position at the time of writing [March 2014] based on information available to the Council. The IDP is thus subject to continual update and review as new information becomes available. It is proposed therefore that it is a 'living document'. The IDP matrix should be read in conjunction with the supporting Evidence Appendices. The following tables give a broad indication of the planned provision, cost and need for infrastructure in South Gloucestershire (to 2027). It sets out planned infrastructure to meet existing deficiencies where information is available, plus that required to meet growth as set out in the South Gloucestershire Local Plan 2006 & Core Strategy (Dec 2013). It thereby indicates requirements for additional infrastructure which would not have been necessary but for the implementation of the proposed development. Where available, items contained within existing S106 agreements for major development sites (or agreements in advanced states of negotiation) have been reflected. For clarity these major sites are Emersons Green Science Park, Charlton Hayes, Harry Stoke, Emersons Green East, Park Farm –Thornbury, North Yate New Neighbourhood & University of the West of England. These sites may from time to time, be subject to change due to negotiation and viability testing instigated by the respective developers. -

Weekly List of Planning Applications and Other Proposals Received by the Council 07 October 2019 – 13 October 2019

WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND OTHER PROPOSALS RECEIVED BY THE COUNCIL 07 OCTOBER 2019 – 13 OCTOBER 2019 The proposals listed over the page have recently been received by the Planning Department. The application documents and plans may be viewed and commented on via the Internet. Please allow 7 days from the above date for the application to appear on the Council’s web site at www.southglos.gov.uk/planning. The submissions listed are also available online at the following one stop shop offices: • Patchway one Stop Shop, Rodway Road, Patchway, South Gloucestershire • Civic Centre, High Street, Kingswood, South Gloucestershire, BS15 9TR • Yate One Stop Shop, Kennedy Way, Yate, South Gloucestershire Some large major applications are also available in hard copy. The Council Offices are open Monday to Thursday between the hours of 8.45 am and 5.00 pm and Friday between the hours of 8.45 am to 4.30 pm. If you have any queries regarding a proposal, please contact our Customer Service Centre on 01454 868004. Any comments on the proposals listed can be made online at the above website or sent in writing to South Gloucestershire Council P.O. BOX 2081 South Gloucestershire BS35 9BP. When commenting please quote the appropriate reference number and site address. All comments should be received within 21 days of the above date. Please note a copy of your comments will appear on the website. ABBREVIATIONS For suffix abbreviations in application number, see Application Type eg. /ADV = Advertisement South Gloucestershire Council Weekly List -

Charlton Hayes Views

Charlton Hayes Views Community News Issue 9 Spring 2016 Welcome and a special welcome to those organising future meetings. This has not In this issue who have just moved to Charlton Hayes. I happened but as new do hope you enjoy your new community, residents move into the community we you have a real opportunity to have a posi- hope that they will take on this valuable Goodbye from me tive impact in your community! Not many role. people get this chance…...what will you do Resident groups, especially on a new devel- Focus on: Debs William, St with your opportunity? opment are a great way to keep in touch Chads and Charlton Hayes This week I found out that there are now with developmental updates/changes. They new outreach worker. over 1100 homes occupied in the develop- act as a forum for new residents to raise ment, which means we’re halfway to the full issues that concern them as well as being Charlton Hayes development 2200 homes being built. I’ve been told that able to influence decision makers. update this will take another 4 years of building. Charlton Hayes is one of the few new devel- Volunteering opportunities Not far really, and then you’ll have all those opment that has a dedicated Stakeholder steering group set up to keep the interest of wonderful things promised in the this community on the agenda of all the Adoption of Roads—latest development plan. developers and business who are building here. The Temporary Green, the opening of the Children and young people pedestrian way between Chessel drive and provision in Patchway. -

Authority's Monitoring Report 2017

AUTHORITY’S MONITORING REPORT 2017 Covering the period 1 April 2016 - 31 March 2017 Contents Chapter Section Page Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 3 2 The South Gloucestershire Context Introduction 7 Demographic Structure 8 Society and Communities 9 Labour Market Characteristics 10 Housing and the Built Environment 11 Transport and Accessibility 12 3 Plans and Policies Planning Policy Context 14 Progress of Local Development Document Preparation 14 4 4.1 Economy 15 4.2 Social 29 4.3 Environment 45 5 Monitoring the Joint Waste Core Introduction 59 Strategy (JWCS) Recycling / Composting 60 Recovery 61 Landfill 62 Municipal Waste Management 63 Map of Major Waste Facilities 65 6 Duty to Co-operate 66 Appendices A. Housing Trajectory B. Commentary on expected housing completions 2017 C. Policies, Sites and Places Plan: Future monitoring indicators The South Gloucestershire Local Authority area Executive Summary This annually produced Authority’s Monitoring Report (AMR) by South Gloucestershire Council monitors the performance of the Council’s planning policies, and sets out progress of the Council’s planning documents. This is the thirteenth AMR published by South Gloucestershire Council and covers the monitoring year of 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. On 8th November the Council adopted its Policies, Sites and Places (PSP) Plan. The PSP Plan replaces the ‘saved’ policies of both the South Gloucestershire Local Plan 2006 (SGLP) and the South Gloucestershire Minerals and Waste Local Plan 2002. Indicators for policies contained within the adopted PSP will be monitored in future AMRs when a full monitoring years’ worth of data is available. Details for future plan monitoring can be found in section 14 of the adopted PSP Plan and features as an appendix. -

Better Or Worse? the Annual Quality of Life Indicators Report for South Gloucestershire

Quality of Life Better or Worse? The annual quality of life indicators report for South Gloucestershire Autumn 2017 Quality of life indicators monitor those things that make an area a good place to live. This report Introduction measures and communicates important facts about South Gloucestershire and aims to demonstrate whether quality of life is getting better, worse or staying the same. Contents Most of the indicators have been monitored Quality of life 3 for several years making it possible to track change over time. There are also more recent Our place 4 indicators that show changes over the last few years. The report suggests there have Our economy 12 been positive changes in some areas and identifies areas where further improvements Our communities 17 are necessary. The indicators will be used by the council and its partners to identify and Our health 22 address priorities for the future. Information about South Gloucestershire Total administrative area: 53,664.7 hectares / 536.6 sq km (Cartesian Measure) Wards: 35 (70 ward Councillors) Population: 277,600 (Office for National Statistics mid-year estimates, 2016) Males: 137,900 Females: 139,800 51,500 (18.6% of total population) Children age (0-15 years): M4 Motorway Working age (16-64 years): 174,700 (62.9% of total population) 'A' Roads Other Roads Pensionable age (65+): 51,400 (18.5% of total population) Railway Line/Station Urban Area Population density: 5.2 persons per hectare / 517.3 persons per sq km Kilometres 2 1 0 1 2 3 © Cro 1 0 1 2 wn Miles Households: 115,820 Co py rig (Valuation Office ht . -

Employment Land Survey

Environment and Community Services Employment Land Survey April 2017 www.southglos.gov.uk Employment Land Survey April 2017 Introduction The Employment Land Survey monitors the availability, distribution and loss of employment and non-residential land and buildings across South Gloucestershire. For the purposes of this report, employment and non-residential includes the following main land uses (for clarity these categories are further subdivided in the tables below): Class A1 = Shops Class A2 = Financial and Professional Services Class A3 = Restaurants and Cafes Class A4 = Drinking Establishments Class A5 = Hot Food Takeaways Class B1 = Business and Light Industry Class B2 = General Industrial Class B8 = Storage and Distribution Class C1 = Hotels Class D1 = Non Residential Institutions Class D2 = Assembly and Leisure Sui Generis = Commercial uses not falling into any of the above categories The Employment Land Survey provides a record of “Gains” and “Losses” (the latter monitored for the first time in the 2007 Survey) of employment and non-residential land and buildings categorised as either: a) new build (on “Greenfield” or undeveloped sites); or b) re-development or change of use (of existing sites and buildings); or c) extension of existing buildings and premises (to create new office, industrial, warehousing space or other developments). The survey does not cover “small-scale” development and restricts analysis to sites of “0.4ha (Gross) and above” or “500 square metres (Gross) and above” across South Gloucestershire. All new development is monitored on sites safeguarded for “employment” (through South Gloucestershire Local Plan Policy E4) and sites identified for safeguarding for “economic development” uses (through Policy CS12 of the Core Strategy). -

Annual Report on Council Performance 2010 Part

Annual Report on Council Performance 2010 Part one – Performance summary Annual Report on Council Performance 2010 1 CONTENTS Part one – Performance summary Page Introduction 3 Purpose of the report 4 Achieving our priorities – our successes 5 What our residents have said about the council 34 What our staff have said about the council 41 External assessment 43 Annual progress against performance indicators 50 Financial information and value for money 54 Progress against other key areas 57 Standards Committee Annual Report 59 Glossary 60 Part two – Performance annexes Annex 1 – Progress against the Community Strategy and Council Plan priorities Annex 2 – Annual progress against performance indicators Annex 3 – Financial information Annex 4 – Environmental Sustainability Annual Progress Summary Annex 5 – Standards Committee Annual Report Annual Report on Council Performance 2009 2 INTRODUCTION We are pleased to introduce our Annual Report on Council Performance for 2010. This report sets out many of the things we have achieved over the past twelve months, and highlights our performance against the priorities set out in the Council Plan as well as a range of statutory and local perfomance indicators. Once again this has been an extremely successful year. We have continued to make considerable progress and remain a low spending council with high performing services and high levels of customer satisfaction. We are recognised both nationally and locally as an excellent council, something we are all very proud of. Our external inspection results remain strong and resident satisfaction with the way the council runs things is amongst the best in the country. Of course, we are not complacent.