How the Situationist International Became What It Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home-Stewart Plagiarism.-Art-As-Commodity-And-Strategies-For-Its-Negation.Pdf

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Plagiarism: art as commodity and strategies for its negation 1. Imitation in art — History — 20th century 2. Art — Reproduction — History — 20th century I. Home, Stewart 702.8'7 N7428 ISBN 0-948518-87-1 Second impression Aporia Press, 1987. No copyright: please copy & distribute freely. INTRODUCTION THIS is a pamphlet intended to accompany the debate that surrounds "The Festival Of Plagiarism", but it may also be read and used separately from any specific event. It should not be viewed as a cat alogue for the festival, as it contains opinions that bear no relation to those of a number of people participating in the event. Presented here are a number of divergent views on the subjects of plagiarism, art and culture. One of the problems inherent in left opposition to dominant culture is that there is no agreement on the use of specific terms. Thus while some of the 'essays' contained here are antagonistic towards the concept of art — defined in terms of the culture of the ruling elite — others use the term in a less specific sense and are consequently less critical of it. Since the term 'art' is popularly associated with cults of 'genius' it would seem expedient to stick to the term 'culture' — in a non-elitist sense — when describing our own endeavours. Although culture as a category appears to be a 'universal' experience, none of its individual expressions meet such a criteria. This is the basis of our principle objection to art — it claims to be 'universal' when it is very clearly class based. -

Redalyc.UMA POÉTICA DA VIDA QUOTIDIANA — GUY DEBORD E a INTERNACIONAL SITUACIONISTA

Aufklärung. Revista de Filosofia ISSN: 2358-8470 [email protected] Universidade Federal da Paraíba Brasil Carvalho, Eurico UMA POÉTICA DA VIDA QUOTIDIANA — GUY DEBORD E A INTERNACIONAL SITUACIONISTA Aufklärung. Revista de Filosofia, vol. 3, núm. 1, enero-junio, 2016, pp. 87-104 Universidade Federal da Paraíba João Pessoa, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=471555231004 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto ISSN: 23189428. V.3, N.1, Abril de 2016. p. 87104 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18012/arf.2016.24891 Received: 18/08/2015 | Revised: 20/08/2015 | Accepted: 15/12/2015 Published under a licence Creative Commons 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) UMA POÉTICA DA VIDA QUOTIDIANA — GUY DEBORD E A INTERNACIONAL SITUACIONISTA [A POETICS OF EVERYDAY LIFE — GUY DEBORD AND THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ] Eurico Carvalho * RESUMO: Neste ensaio, procedemos à ABSTRACT: In this paper, I will focus on análise do conceito situacionista de vida the nature of the Situationist concept of quotidiana, tendo em vista evidenciar não everyday life, in order to highlight not só a riqueza que lhe é própria, mas only its objective content but also its também a respectiva ambiguidade. Além ambiguity. Moreover, I will demonstrate disso, fazse a demonstração de que existe, that there is, from the perspective of a em termos de uma poética do quotidiano, e poetics of everyday life, and in spite of the pese embora a diversidade das fases de diversity of development stages of the desenvolvimento da Internacional Situationist International, an undeniable Situacionista, uma indiscutível unidade do unity of its revolutionary program. -

Diogene Éditions Libres

diogene éditions libres publié en pdf par diogene.ch copyright/copyleft l'or des fous/diogene.ch 2008. Le texte est disponible selon les termes de la licence libre "créative commons" (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/fr/%20) La Volonté de paresse Philippe Godard Paul Lafargue Pauline Wagner Raoul Vaneigem L'or des fous É D I T E U R 2 Merci à Jean-Luc Oudry pour l’illustration de la couverture, à Pascal Lécaille pour la préparation des textes, à Frédérique Béchu pour la réalisation du livre et à Jean Pencreac’h pour la correction. © L’or des fous éditeur, Nyons, 2006 ISBN : 2-915995-06-0 3 « La paresse est jouissance de soi ou n’est pas. N’espérez pas qu’elle vous soit accordée par vos maîtres ou par leurs dieux. On y vient comme l’enfant par une naturelle inclination à chercher le plaisir et à tourner ce qui le contrarie. C’est une simplicité que l’âge adulte excelle à compliquer. » Raoul Vaneigem Réaffirmant follement le désir de désirer un autre monde, de rêver, de poétiser et de vivre une vie authentique, voici ce livre qui, cheminant de Philippe Godard à Raoul Vaneigem, en compagnie de Paul Lafargue et de Pauline Wagner, chante la mélodie du vivant et le droit à l’amour. Trois chevaliers et une dame récusent la quête frénétique du travail, qui ravage aujourd’hui les esprits pour appeler la paresse à la rescousse. En 1880, Le Droit à la paresse ou La Réfutation du droit au travail de Paul Lafargue paraissait en feuilleton dans l’hebdomadaire L’Égalité ; incarcéré à la prison de Sainte-Pélagie en 1883, il ajoute quelques notes pour une prochaine réédition. -

Occupy the Fun Palace Britt Eversole

thresholds 41 Spring 2013, 32-45 OCCUPY THE FUN PALACE BRITT EVERSOLE During the 1968 holiday season, a dozen people and one Santa Claus impersonator stormed Selfridges, a Daniel Burnham-designed department store on London’s posh Oxford Street. Confused customers gathered when Father Christmas and his helpers pulled goods from the shelves and began giving them away. When clerks intervened, a melee erupted, arrests ensued, and police were forced to make crying children return unpurchased toys and candy. In the aftermath, Londoners found leaflets bearing an anti-consumer diatribe against the holidays as the palliative to another year of pointless labor ending in unaffordable shopping and perfunctory celebration (Figure 1). Chiding Britons that they did not deserve Christmas because they had not worked hard enough, this year’s festivities were a “punishment…a duty to be cheerful, to play the fool, let down your hair as soon as they switch on the lights and raise the curtain.” A call to arms ended the invective: Let’s smash the whole great deception. Occupy the Fun Palace and really set the swings going. Grab the gifts and really give them. Light up Oxford Street and dance around the fire.1 This vicious potlatch was one of many guerilla actions by the English Situation- ist-inspired group King Mob, named after the 1780 Gordon Riots in which revolt- ing prison inmates freed themselves by the authority of “His Majesty, King Mob.” During the late 1960s, they assaulted British culture with pranks, profane leafleting and poster campaigns, and by vandalizing buildings and infrastructure with erudite phrases, the most famous being a thesis on an Underground embankment: SAME THING DAY AFTER DAY–TUBE–WORK–DINER [sic]–WORK–TUBE–ARMCHAIR–T.V.– SLEEP–TUBE–WORK–HOW MUCH MORE CAN YOU TAKE–ONE IN TEN GO MAD– ONE IN FIVE CRACKS UP. -

Apocalypse and Survival

APOCALYPSE AND SURVIVAL FRANCESCO SANTINI JULY 1994 FOREWORD !e publication of the Opere complete [Complete Works] of Giorgio Cesa- rano, which commenced in the summer of 1993 with the publication of the "rst comprehensive edition of Critica dell’utopia capitale [Critique of the uto- pia of capital], is the fruit of the activity of a group of individuals who were directly inspired by the radical critique of which Cesarano was one of the pioneers. In 1983, a group of comrades who came from the “radical current” founded the Accademia dei Testardi [Academy of the Obstinate], which published, among other things, three issues of the journal, Maelström. !is core group, which still exists, drew up a balance sheet of its own revolution- ary experience (which has only been partially completed), thus elaborating a preliminary dra# of our activity, with the republication of the work of Gior- gio Cesarano in addition to the discussion stimulated by the interventions collected in this text.$ In this work we shall seek to situate Cesarano’s activity within its his- torical context, contributing to a critical delimitation of the collective envi- ronment of which he formed a part. We shall do this for the purpose of more e%ectively situating ourselves in the present by clarifying our relation with the revolutionary experience of the immediate past. !is is a necessary theoret- ical weapon for confronting the situation in which we "nd ourselves today, which requires the ability to resist and endure in totally hostile conditions, similar in some respects to those that revolutionaries had to face at the begin- ning of the seventies. -

00A Inside Cover CC

Access Provided by University of Manchester at 08/14/11 9:17PM GMT 05 Thoburn_CC #78 7/15/2011 10:59 Page 119 TO CONQUER THE ANONYMOUS AUTHORSHIP AND MYTH IN THE WU MING FOUNDATION Nicholas Thoburn It is said that Mao never forgave Khrushchev for his 1956 “Secret Speech” on the crimes of the Stalin era (Li, 115–16). Of the aspects of the speech that were damaging to Mao, the most troubling was no doubt Khrushchev’s attack on the “cult of personality” (7), not only in Stalin’s example, but in principle, as a “perversion” of Marxism. As Alain Badiou has remarked, the cult of personality was something of an “invariant feature of communist states and parties,” one that was brought to a point of “paroxysm” in China’s Cultural Revolution (505). It should hence not surprise us that Mao responded in 1958 with a defense of the axiom as properly communist. In delineating “correct” and “incorrect” kinds of personality cult, Mao insisted: “The ques- tion at issue is not whether or not there should be a cult of the indi- vidual, but rather whether or not the individual concerned represents the truth. If he does, then he should be revered” (99–100). Not unex- pectedly, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and “the correct side of Stalin” are Mao’s given examples of leaders that should be “revere[d] for ever” (38). Marx himself, however, was somewhat hostile to such practice, a point Khrushchev sought to stress in quoting from Marx’s November 1877 letter to Wilhelm Blos: “From my antipathy to any cult of the individ - ual, I never made public during the existence of the International the numerous addresses from various countries which recognized my merits and which annoyed me. -

MACBA Coll Artworks English RZ.Indd

of these posters carry the titles of Georges Perec’s novels, but Ignasi Aballí very few were actually made into Flms. We might, however, Desapariciones II (1 of 24), 2005 seem to remember some of these as Flms, or perhaps simply imagine we remember them. A cinema poster, aker it has accomplished its function of announcing a Flm, is all that’s lek of the Flm: an objective, material trace of its existence. Yet it also holds a subjective trace. It carries something of our own personal history, of our involvement with the cinema, making us remember certain aspects of Flms, maybe even their storylines. As we look at these posters we begin to create our own storylines, the images, text and design suggesting di©erent possibilities to us. By fabricating a tangible trace of Flms that were never made, Desaparicions II brings the Flms into existence and it is the viewer who begins to create, even remember these movies. The images that appear in the posters have all been taken from artworks made by Aballí. As the artist has commented: ‘In the case of Perec, I carried out a process of investigation to construct a Fction that enabled me to relate my work to his and generate a hybrid, which is something directly constructed by me, though it includes real elements I found during the documentation stage.’ 3 Absence, is not only evident in the novel La Disparition, but is also persistent in the work Aballí; mirrors obliterated with Tipp-Ex, photographs of the trace paintings have lek once they have been taken down. -

The Revolution of Everyday Life

The Revolution of Everyday Life Raoul Vaneigem 1963–1965 Contents Dedication ............................................. 5 Introduction ............................................ 5 Part I. The Perspective of Power 7 Chapter 1. The Insignificant Signified .............................. 8 1 ................................................ 8 2 ................................................ 9 3 ................................................ 9 4 ................................................ 11 Impossible Participation or Power as the Sum of Constraints 12 Chapter 2. Humiliation ...................................... 12 1 ................................................ 12 2 ................................................ 14 3 ................................................ 16 4 ................................................ 17 Chapter 3. Isolation ........................................ 17 1 ................................................ 17 2 ................................................ 19 Chapter 4. Suffering ........................................ 20 2 ................................................ 22 3 ................................................ 23 4 ................................................ 24 Chapter 5. The Decline and Fall of Work ............................. 25 Chapter 6. Decompression and the Third Force ......................... 28 Impossible Communication or Power as Universal Mediation 32 Chapter 7. The Age of Happiness ................................. 32 1 ............................................... -

Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA 661 Millwood Avenue, Ste 206 Winchester, Virginia USA 22601

LORNE BAIR RARE BOOKS CATALOG 26 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA 661 Millwood Avenue, Ste 206 Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with or- der and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ strict standards of professionalism and ethics. CONTENTS OF THIS CATALOG _________________ AFRICAN AMERICANA Items 1-35 RADICAL & PROLETARIAN LITERATURE Items 36-97 SOCIAL & PROLETARIAN LITERATURE Items 98-156 ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Items 157-201 INDEX & REFERENCES PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. ANDREWS, Matthew Page Heyward Shepherd, Victim of Violence. [Harper’s Ferry?]: Heyward Shepherd Memorial Association, [1931]. First Edition. Slim 12mo (18.5cm.); original green printed card wrappers, yapp edges; 32pp.; photograph. -

Cornelius Castoriadis

Cornelius Castoriadis An Interview The following interview with Cornelius Castoriadis took place at RP: What was the political situation in Greece at that time? the University of Essex, in late Feburary 1990. Castoriadis is a leading figure in the thought and politics ofthe postwar period in Castoriadis: 1935 was the eve of the Metaxas dictatorship which France. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s he was a member lasted throughout the war and the occupation. At that time, in the of the now almost legendary political organization, Socialisme last year of my secondary education, I joined the Communist ou Barbarie, along with other currently well-known figures, such Youth, which was underground, of course. The cell I was in was as Claude Lefort andlean-Franaois Lyotard. Unlike some ofhis dissolved because all my comrades were arrested. I was lucky contemporaries, however, he has remained firm in the basic enough not to be arrested. I started political activity again after the political convictions ofhis activist years . He may be better known beginning of the occupation. First, with some comrades, in what to some Radical Philosophy readers under the name of Paul now looks like an absurd attempt to change something in the Cardan, the pseudonym which appeared on the cover of pam policies of the Communist Party. Then I discovered that this was phlets published during the 1960s by 'Solidarity', the British just a sheer illusion. I adhered to the Trotskyists, with whom I counterpart to Socialisme ou Barbarie. worked during the occupation. After I went to France in 1945/46, Castoriadis is notable for his effort to rescue the emancipa I went to the Trotskyist party there and founded a tendency against tory impulse of Marx' s thought - encapsulated in his key notion the official Trotskyist line of Russia as a workers' state. -

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter I Publishing Bordiga's texts on Russia and writing an introduction to them was rather repugnant to us. The Russian revolution and its involution are indeed some of the greatest events of our century. Thanks to them, a horde of thinkers, writers, and politicians are not unemployed. Among them is the first gang of speculators which asserts that the USSR is communist, the social relations there having been transformed. However, over there men live like us, alienation persists. Transforming the social relations is therefore insufficient. One must change man. Starting from this discovery, each has 'functioned' enclosed in his specialism and set to work to produce his sociological, ecological, biological, psychological etc. solution. Another gang turns the revolution to its account by proving that capitalism can be humanised and adapted to men by reducing growth and proposing an ethic of abstinence to them, contenting them with intellectual and aesthetic productions, restraining their material and affective needs. It sets computers to work to announce the apocalypse if we do not follow the advice of the enlightened capitalist. Finally there is a superseding gang which declares that there is neither capitalism nor socialism in the USSR, but a kind of mixture of the two, a Russian cocktail ! Here again the different sciences are set in motion to place some new goods on the over-saturated market. That is why throwing Bordiga into this activist whirlpool -

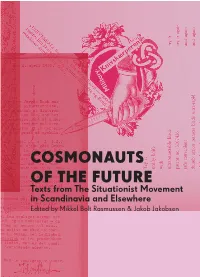

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263.