Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irak: Attentats Et Reconstruction Politique

INSTITUT URD DE PARIS Bulletin de liaison et d'information I N°220-221 I JUILLET -AOUT 2003 . " La publication de ce Bulletin bénéficie de subventions du Ministère français des Affaires étrangères (DCCID) et du Fonds d'action et de soutien pour l'intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (FAS/LD) Ce bulletin paraît en français et anglais Prix au numéro: France: 6 € - Etranger: 7,5 € Abonnement annuel (12 numéros) France: 60 € - Etranger: 75 € Périodique mensuel Directeur de la publication: Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire: 659 13 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tél. : 01- 48 24 64 64 - Fax: 01- 48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Sommaire: • IRAK: ATTENTATS ET RECONSTRUCTION POLITIQUE. • PÉRIPLE DIPLOMATIQUE DE N. BARZANI ET J. TAlABANI , , • CRISE ENTRE WASHINGTON ET ANKARA : L'ARMEE AMERICAINE ARRÊTE À SOUlEIMANIEH ONZE MILITAIRES TURCS Ii SOUPÇONNÉS DE COMPLOT" CONTRE lE GOUVERNEUR KURDE DE KIRKOUK • CINQUIÈME AUDIENCE DU PROCÈS DE lEYlA ZANA ET DE SES . COllÈGUES: lES OBSERVATEURS DÉNONCENT lA Ii PARODIE DE JUSTICf" • DAMAS: lES ASSOCIATIONS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME lOCALES DÉNONCENT lES ARRESTATIONS DES KURDES , . • STRASBpURG : lA TURQUIE CONDAMNEE PAR lA COUR EUROPEENNE DES DROITS DE L'HOMME • AINSI QUE ... • lU DANS lA PRESSE TURQUE IRAK: à Saddam Hussein, des « islamistes sans frontières» en djihad contre les ATTENTATS ET RECONSTRUCTION POLITIQUE occidentaux, des agents des services de renseignement iranien (Italaat) agissant seuls ou de concert, sont tenus pour responsables de ces 'ÉTÉ 2003 aura été marqué municipaux, gouverneurs) et la actions qui ne visent pas que les dans l'Irak d'après Saddam remise en état des écoles, des Américains. -

The Ineffectiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-29-2011 The neffecI tiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The aC se of Iraq Manuel De Leon Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11081006 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation De Leon, Manuel, "The neffeI ctiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The asC e of Iraq" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 463. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/463 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF MULTILATERAL SANCTIONS REGIMES UNDER GLOBALIZATION: THE CASE OF IRAQ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Manuel De Leon 2011 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Manuel De Leon, and entitled The Ineffectiveness of Multilateral Sanctions Regimes Under Globalization: The Case of Iraq, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Mohiaddin Mesbahi _______________________________________ Dario Moreno _______________________________________ Astrid Arraras _______________________________________ Ronald W. Cox, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 29, 2011 The dissertation of Manuel De Leon is approved. -

A Influência Dos Ulemás Xiitas Nas Transformações

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA SOCIAL RENATO JOSÉ DA COSTA A INFLUÊNCIA DOS ULEMÁS XIITAS NAS TRANSFORMAÇÕES POLÍTICAS OCORRIDAS NO IRÃ DURANTE O SÉCULO XX – O WILAYAT AL-FAQIH E O PRAGMATISMO DOS AIATOLÁS COMO INVIABILIZADORES NA EXPANSÃO DA REVOLUÇÃO IRANIANA Versão Corrigida São Paulo 2013 1 RENATO JOSÉ DA COSTA A INFLUÊNCIA DOS ULEMÁS XIITAS NAS TRANSFORMAÇÕES POLÍTICAS OCORRIDAS NO IRÃ DURANTE O SÉCULO XX – O WILAYAT AL-FAQIH E O PRAGMATISMO DOS AIATOLÁS COMO INVIABILIZADORES NA EXPANSÃO DA REVOLUÇÃO IRANIANA Tese de doutorado apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas (FFLCH) da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Programa de Pós-graduação stricto sensu em História Social, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências Sociais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jorge Luís da Silva Grespan Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Daniel Elias Farah Versão Corrigida São Paulo 2013 Catalogação da Publicação Serviço de Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Costa, Renato José da. A influência dos ulemás xiitas nas transformações políticas ocorridas no Irã durante o século XX: o wilayat al-faqih e o pragmatismo dos aiatolás como inviabilizadores na expansão da Revolução Iraniana / Renato José da Costa. – São Paulo: Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, 2013. xvii, 292f. : 50il.; 29,7 cm. Orientadores: Jorge Luís da Silva Grespan e Paulo Daniel Elias Farah. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Departamento de História Social, 2013. -

(Tyler) Priest

Richard (Tyler) Priest Associate Professor Departments of History and Geographical and Sustainability Sciences 280 Schaeffer Hall University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242 (319) 335-2096 [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY 1. Education Ph.D. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1996) M.A. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1990) B.A. Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota, History (June 1986) 2. Professional and Academic Positions 2012-present Associate Professor of History and Geographical and Sustainability Sciences, University of Iowa 2004-2012 Director of Global Studies and Clinical Professor, C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston 2010-2011 Senior Policy Analyst, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling 2002-2005 Historical Consultant, History of Offshore Oil and Gas Industry in Southern Louisiana Research Project, Minerals Management Service, 2002-2005 2000-2002 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Houston-Clear Lake 1998-2001 Chief Historian, Shell Oil History Project 1997-1998 Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for the Americas, University of Houston 1996-1997 Researcher and Author, Brown & Root Inc. History Project on the Offshore Oil Industry 1994-1995 Visiting Instructor, Middlebury College 3. Honors and Awards Collegiate Teaching Award, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Iowa, 2017 Award for Distinguished Achievement in Publicly Engaged Research, University of Iowa, 2016 Partners in Conservation Award, -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Sudanese literature in English translation: an analytical study of the translation with a historical introduction to the literature. Thorraya Soghayroon School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2010. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Sudanese Literature in English Translation: An Analytical Study of the Translation with a Historical Introduction to the Literature Thorraya Soghayroon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the University of Westminster for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2010 Abstract This thesis sets out to record, analyze, and assess modern Sudanese literature within its historical, cultural, and political context. It highlights the diversity and distinctiveness of that literature, the wide range of its themes, and the resilience and complex background of its major practitioners. -

United States Attorney Southern District of New York

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE OCTOBER 1, 2007 YUSILL SCRIBNER REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 TEXAS OILMAN ENTERS MID-TRIAL GUILTY PLEA TO CHARGES OF CONSPIRING TO MAKE ILLEGAL PAYMENTS TO THE FORMER GOVERNMENT OF IRAQ MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced the guilty plea today of OSCAR S. WYATT, JR., 83, of Houston, Texas. Nearly four weeks into his criminal trial, and on the eve of the Government resting its case, WYATT pleaded guilty to participating in a scheme to pay illegal surcharges to the former Government of Iraq in connection with the purchase of crude oil in the United Nations Oil-for-Food Program between mid-2000 and 2003. The plea was entered in Manhattan federal court before United States District Judge DENNY CHIN. Under the terms of his plea agreement, WYATT will forfeit over $11 million and begin serving his prison sentence by January 2, 2008. According to the evidence at trial and statements made during WYATT's guilty plea: The United Nations established the Oil-for-Food Program in the mid-1990's as an exception to the comprehensive international sanctions on SADDAM HUSSEIN’s regime in Iraq. Under the Program, the former Government of Iraq was allowed to sell a limited quantity of oil, and the proceeds from those oil sales were deposited into an escrow bank account managed by the United Nations. That money could only be used for humanitarian purposes approved by the United Nations, including food and medicine for the Iraqi people and reparations to the victims of the Hussein regime’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. -

Partners in Making Cancer History 2012

MD ANDERSON CANCER CENTER | ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 PARTNERS IN MAKING CANCER HISTORY® The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center gratefully acknowledges the following individuals, foundations, organizations and others who made a commitment of $1,000 or more from Sept. 1, 2011, to Aug. 31, 2012. UP, UP AND AWAY Broadcast journalist Miles O’Brien interviews Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin Group, before more than 750 guests during the 22nd annual A Conversation With a Living Legend® in Dallas. The discussion covered aviation, space travel and the Virgin brand, among other topics. The event raised more than $855,000. A Mr. and Mrs. Gerhard P. Adenacker Ms. Patrice Alessandra American Association for Cancer Research Mr. and Mrs. Eric Anderson Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Charles Alexander and LaVerne Alexander American Asthma Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Gregory Mark Anderson Foundation Mrs. Henrietta K. Alexander American Cancer Society Mr. and Mrs. Jack R. Anderson A & A Cattle Company Mr. Richard C. Adkerson Mr. James M. Alexander The American Endowment Foundation Mrs. Jacqueline R. Anderson Carol and Steve Aaron Mr. and Mrs. Louis K. Adler Joan and Stanford Alexander American Heart Association-Texas Mr. James Scott Anderson Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Aaron The Adler Foundation Mr. and Mrs. John D. Alexander, Jr. American Institute for Cancer Research Mr. and Mrs. Jeff R. Anderson Abbott Fund AdvoCare International, L.P. Mr. Leslie L. Alexander American International Group, Inc. John Henry and Dora Anderson Dr. and Mrs. Christian R. Abee Aflac Leslie L. Alexander Foundation, Inc. The American Kennel Club Canine Health Karen and Charles Anderson Mrs. -

Changing the Landscape of A&D

nOVeMBER 2012 cSPE GulfO COaSNNECTt Section NEwSlEtter Changing the Landscape Open Officer of A&D pOsitiOns General MtG P. 11 P. 9 YOung prOfessiOnals VOlunteer OppOrtunities Distinguished Lecturer Program: CommuNity Service P. 29 A Methodology to Design Exploratory Wells Then and Now P. 5 P.26 Buddy Woodroof spegcs.org NOVEMBER 2012 1 SPE-GCS cONNECT cONNECT Information chairMan’s Newsletter Committee ChairmaN Kim Tran SALES Pat Stone CoRNER BOaRD LIAISON Valerie Martone Steve BaumgaRtner EDitor/DESiGN Deuce Creative 2012-2013 SPE-GCS Chair deucecreative.com The SPE Gulf Coast Section relies on volunteers to plan and conduct all For comments, contributions, or delivery problems, contact [email protected]. our member programs and community activities. What is volunteerism? The deadline for each issue is 6 weeks The dictionary definition is “the policy or practice of volunteering one’s before publication on the first of each time or talents for charitable, educational, or other worthwhile activities, month. The SPE Gulf Coast Section especially in one’s community”. What is a volunteer? The dictionary newsletter is published eleven times each program year and is mailed to more than definitions are “a person who voluntarily offers himself or herself for a 15,000 SPE members in Houston. service or undertaking” and “a person who performs a service willingly and without pay”. As we organize technical programs and community SPE Houston Office activities for the remainder of 2012-13 program year in the Gulf Coast Section, please reflect on the following questions before you volunteer. Gulf Coast Section Manager Kathy MacLennan I have answered question number one for you. -

The Gulf War's Afterlife

The Scholar THE GULF WAR’S AFTERLIFE: DILEMMAS, MISSED OPPORTUNITIES, AND THE POST-COLD WAR ORDER UNDONE SAMUEL HELFONT 25 The Gulf War’s Afterlife: Dilemmas, Missed Opportunities, and the Post-Cold War Order Undone The Gulf War is often remembered as a “good war,” a high- tech conflict that quickly and cleanly achieved its objectives. Yet, new archival evidence sheds light on the extended fallout from the war and challenges this neat narrative. The Gulf War left policymakers with a dilemma that plagued successive U.S. administrations. The war helped create an acute humanitarian crisis in Iraq, and the United States struggled to find a way to contain a still recalcitrant Saddam Hussein while alleviating the suffering of innocent Iraqis. The failure of American leaders to resolve this dilemma, despite several chances to do so, allowed Saddam’s regime to drive a wedge into the heart of the American-led, post-Cold War order. While in the short term the war seemed like a triumph, over the years its afterlife caused irreparable harm to American interests. n June 1991, nearly 5 million onlookers en- American politics. Both the Clinton and Obama ad- thusiastically welcomed American troops ministrations admired the way President George returning home from the Gulf War as they H. W. Bush handled the conflict.5 Despite some marched in a ticker-tape parade through handwringing about Saddam Hussein remaining in NewI York City’s “Canyon of Heroes.”1 This image power and the fact that there was no World War of the Gulf War as a triumph has proved endur- II-style surrender, the conflict is still remembered ing. -

Strategic Personality and the Effectiveness of Nuclear Deterrence: Deterring Iraq and Iran

INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES DEFENSE THREAT REDUCTION AGENCY Strategic Personality and the Effectiveness of Nuclear Deterrence: Deterring Iraq and Iran Caroline F. Ziemke September 2001 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. IDA Paper P-3658 Log: H 01-001983 SPONSOR: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Dr. Jay Davis, Director Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Dr. Randall S. Murch, Director BACKGROUND: The Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) was founded in 1998 to integrate and focus the capabilities of the Department of Defense (DoD) that address the weapons of mass destruction threat. To assist the Agency in its primary mission, the Advanced Systems and Concepts Office (ASCO) develops and maintains an evolving analytical vision of necessary and sufficient capabilities to protect United States and Allied forces and citizens from WMD attack. ASCO is also charged by DoD and by the U.S. Government generally to identify gaps in these capabilities and initiate programs to fill them. It also provides supprt to the Threat Reduction Advisory Committee (TRAC), and its Panels, with timely, high quality research. ASCO ANALYTICAL SUPPORT: The Institute for Defense Analyses has provided analytical support to DTRA since the latter’s inception through a series of projects on chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons issues. This work was performed for DTRA under contract DASW01 98 C 0067, Task DC-6-1990. SUPERVISING PROJECT OFFICER: Dr. Anthony Fainberg, Chief, Advanced Concepts and Technologies Division, ASCO, DTRA, (703) 767-5709. © 2001 INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES: 1801 N. Beauregard Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1772. Telephone: (703) 845-2000. Project Coordinator: Dr. Brad Roberts, Research Staff Member, (703) 845-2489. -

JTHG Corridor

Journey Through Hallowed Ground A National Park Service scheme, run by a “socially-conscious” aristocracy, designed to radically transform a million acres of Virginia’s heartland and to impose the “appropriate” quality of life on people of the Piedmont. 2 © March, 2006, The Virginia Land Rights Coalition POB 85 McDowell, Virginia FOC 24458 540-396-6217 L. M. Schwartz, Chairman www.vlrc.org Reproduction or publication for any purpose or in any commercial media outlet, news source or internet site, either in full or partially, is strictly prohibited without written permission. Printed and bound copies of this report are available in color or black and white. Please inquire. For more information about preserving America’s Constitutionally protected Rights to Life, Liberty and Property, call, write or visit our website. This report may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information, see: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml “Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in hope that truth may find a place in history and descend to posterity. History is not the relating of campaigns and battles, and generals or other individuals, but that which shows principles. The principles for which the South contended were government by the people; that is, government by the consent of the governed, government limited and local, free of consolidated power. -

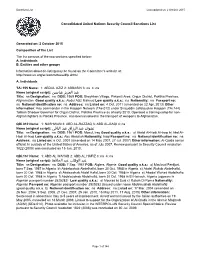

Name (Original Script): ﻦﯿﺳﺎﺒﻋ ﺰﻳﺰﻌﻟا ﺪﺒﻋ ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ

Sanctions List Last updated on: 2 October 2015 Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List Generated on: 2 October 2015 Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found on the Committee's website at: http://www.un.org/sc/committees/dfp.shtml A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. QDi.012 Name: 1: NASHWAN 2: ABD AL-RAZZAQ 3: ABD AL-BAQI 4: na ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺒﺎﻗﻲ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1961 POB: Mosul, Iraq Good quality a.k.a.: a) Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi b) Abd Al- Hadi Al-Iraqi Low quality a.k.a.: Abu Abdallah Nationality: Iraqi Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 6 Oct. 2001 (amended on 14 May 2007, 27 Jul.