The Plays and Players Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare in Love

FEB Shakespeare 26 MAR in Love 29 Based on the screenplay by Marc Norman & Tom Stoppard Adapted for the stage by Lee Hall Music by Alex Bechtel Directed by Matt Pfeiffer Welcome to Shakespeare in Love. Every year, many of you cry out to us “Dear God, no more Shakespeare!” While others plead “I loved your Winter’s Tale, your Richard III. Please put on Midsummer. I beg you for a Twelfth Night.” With Shakespeare In Love, the Purists and the Never Barders may unite to curse us with a plague on both our houses, but if they — and you — are someone who loves love, well then . Here is a love letter to romantic love, to the theatre, and to the rebellious, transgressive, mysterious, and glorious madness of both. Whether you keep Shakespeare close to your heart or far from it, we invite you to celebrate what he loved most: the stage, its players, poetry . and a dog. Zak Berkman, Producing Director Lend me your ears Matt Pfeiffer, Director I’ve been really blessed to spend most of my career working on the plays of William Shakespeare. I believe his plays are foundational to Western culture. Love him or hate him, his infuence is an essential part of our understanding of stories and storytelling. And I’ve had the privilege for the last six years of fostering a specifc approach to his plays. I found that attempting to be in conversation with the principals of the theatre practices of Shakespeare’s time was a good starting place—not so much aesthetically, but logistically. -

To Play the Forrest Theatre for One Week Only As Part of Kimmel Center’S Broadway Philadelphia Season! Tuesday, February 13 - Sunday, February 18, 2018

Tweet it! Sugar… butter… flour… @WaitressMusical comes to the @KimmelCenter – 2/13-2/18! Visit kimmelcenter.org for more info. #WaitressMusical #BWYPHL Press Contacts: Monica Robinson Lisa Jefferson 215-790-5847 267-765-3723 [email protected] [email protected] TO PLAY THE FORREST THEATRE FOR ONE WEEK ONLY AS PART OF KIMMEL CENTER’S BROADWAY PHILADELPHIA SEASON! TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 13 - SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 18, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center and The Shubert Organization are thrilled to announce Waitress will play the Forrest Theatre for a limited one-week engagement from Tuesday, February 13 through Sunday, February 18, 2018. Brought to life by a groundbreaking all-female creative team, this irresistible new hit features original music and lyrics by 6-time Grammy® nominee Sara Bareilles ("Brave," "Love Song"), a book by acclaimed screenwriter Jessie Nelson (I Am Sam), choreography by Lorin Latarro (Les Dangereuse Liasons, Waiting For Godot) and direction by Tony Award® winner Diane Paulus (Hair, Pippin, Finding Neverland). “What an honor to have this incredibly heartwarming show make its Philadelphia debut as part of our 2017-18 Broadway Philadelphia season,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Brought to Broadway by a group of imaginative, strong women, this film-turned- musical tells the story of another strong woman forging her own path, something to which we all can relate.” Inspired by Adrienne Shelly's beloved film, Waitress tells the story of Jenna - a waitress and expert pie maker. Jenna dreams of a way out of her small town and loveless marriage. -

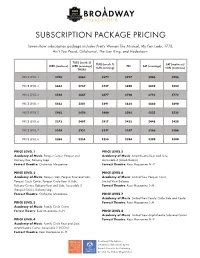

Subscription Package Pricing

2020 2021 SUBSCRIPTION PACKAGE PRICING Seven-show subscription package includes Pretty Woman The Musical, My Fair Lady, 1776, Ain’t Too Proud, Oklahoma!, The Lion King, and Hadestown. TUES (week 2) TUES (week 1) SAT (matinees) WED (matinee) WED (evenings) FRI SAT (evenings) SUN (evening) SUN (matinees) THURS PRICE LEVEL 1 $745 $862 $872 $927 $946 $956 PRICE LEVEL 2 $664 $737 $747 $800 $832 $852 PRICE LEVEL 3 $594 $667 $677 $720 $752 $772 PRICE LEVEL 4 $523 $581 $591 $634 $660 $690 PRICE LEVEL 5 $402 $450 $460 $503 $525 $535 PRICE LEVEL 6 $373 $407 $417 $433 $448 $458 PRICE LEVEL 7 $348 $331 $341 $357 $366 $366 PRICE LEVEL 8 $268 $258 $258 $284 $290 $300 PRICE LEVEL 1 PRICE LEVEL 5 Academy of Music: Parquet Center, Parquet and Academy of Music: Amphitheatre Rear and Side; Balcony Box, Balcony Loge Accessible 4 (Amphitheatre) Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P PRICE LEVEL 2 PRICE LEVEL 6 Academy of Music: Parquet Side, Parquet Rear and Side, Academy of Music: Limited View Parquet Circle, Parquet Circle Center, Parquet Circle Rear & Side, Limited View Balcony Balcony Center, Balcony Rear and Side, Accessible 2 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M (Parquet Circle), Balcony Loge Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine PRICE LEVEL 7 Academy of Music: Limited View Family Circle Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 3 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M Academy of Music: Family Circle Center Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H PRICE LEVEL 8 Academy of Music: Limited View Amphitheatre Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 4 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P Academy of Music: Family Circle Rear and Side; Amphitheatre Center, Accessible 3 (FCCIR) Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H Broadway Philadelphia is presented collaboratively by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization 2020 2021 ADD-ON PRICING Prices listed below are inclusive of ticketing fees, excluding the $4 per order fee. -

Saturday-Night-Fever.Pdf

® PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA PLAYBILL.COM PLAYBILLVAULT.PLAYBILL.COMCOM PLAYBILLVAULT.COM 06-01 SatNightFever2_Live.indd 1 5/12/17 3:22 PM Dear Theatregoer, Welcome to Saturday Night Fever! I am so glad to have you as our guest for this incredible season finale. The energy this cast brings to the stage will make you want to get up and dance to the iconic music from the legendary Bee Gees. I’m thrilled to share this electrifying production with you. Next season the excitement continues on our Mainstage with a spectacular line-up. The 2017–18 season will begin with Broadway’s classic Tony Award-winning Best Musical A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum. You’ll meet Pseudolus, a crafty slave who struggles to win the hand of a beautiful, but slow-witted, courtesan for his young master. The plot twists and turns with cases of mistaken identity, slamming doors and a bevy of beautiful showgirls. I think this musical comedy is one of the funniest Broadway shows ever written, and I’m sure you’ll agree. During the holiday season we’ll look to a brighter “tomorrow” with one of the world’s best-loved musicals Annie. This Tony Award- winning Best Musical features some of the greatest musical theatre Photo: Mark Garvin hits ever written including “It’s the Hard Knock Life,” “Easy Street,” and “Tomorrow.” I’m excited to share this exciting production with you and your family, as Annie fills our hearts with joy! Our season continues with The Humans. This comedy won more than 20 Best Play awards in 2016, including the Tony Award. -

The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia 4-RC-21019 6-9-05

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD REGION FOUR CONCERTO SOLOISTS d/b/a THE CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF PHILADELPHIA1 Employer and Case 4–RC–21019 PHILADELPHIA MUSICIANS’ UNION LOCAL 77, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS, AFL-CIO2 Petitioner REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S DECISION AND DIRECTION OF ELECTION The Employer, The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, is a small, elite orchestra which performs at concerts and other engagements. The Petitioner, Philadelphia Musicians’ Union Local 77, has filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board under Section 9(c) of the National Labor Relations Act seeking to represent a unit of the Musicians who perform in the Chamber Orchestra. There are about 33 Musicians in the petitioned-for unit. The Employer contends that the Musicians are independent contractors and thus are excluded from the coverage of the Act. A hearing officer of the Board held a hearing, and the parties filed briefs. I have considered the evidence and the arguments presented by the parties, and as discussed below, I have concluded that the Musicians are statutory employees. Accordingly, I am directing an election in a bargaining unit of the Employer’s Musicians.3 To provide a context for my discussion, I will first present a brief overview of the Employer’s operations. Then, I will review the factors that must be evaluated in determining independent contractor status and present in detail the facts and reasoning that support my conclusion that the Musicians are statutory employees. 1 The Employer’s name was amended at the hearing. 2 The Petitioner’s name was amended at the hearing. -

Septa-Phila-Transit-Street-Map.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q v A Mill Rd Cricket Kings Florence P Kentner v Jay St Linden Carpenter Ho Cir eb R v Newington Dr Danielle Winding W Eagle Rd Glen Echo Rd B Ruth St W Rosewood Hazel Oak Dr Orchard Dr w For additional information on streets and b v o o r Sandpiper Rd A Rose St oodbine1500 e l Rock Road A Surrey La n F Cypress e Dr r. A u Dr Dr 24 to Willard Dr D 400 1 120 ant A 3900 ood n 000 v L v A G Norristown Rd t Ivystream Rd Casey ie ae er Irving Pl 0 Beachwoo v A Pine St y La D Mill Rd A v Gwynedd p La a Office Complex A Rd Br W Valley Atkinson 311 v e d 276 Cir Rd W A v Wood y Mall Milford s r Cir Revere A transit services ouside the City of 311 La ay eas V View Dr y Robin Magnolia R Daman Dr aycross Rd v v Boston k a Bethlehem Pike Rock Rd A Meyer Jasper Heights La v 58 e lle H La e 5 Hatboro v Somers Dr v Lindberg Oak Rd A re Overb y i t A ld La Rd A t St ll Wheatfield Cir 5 Lantern Moore Rd La Forge ferson Dr St HoovStreet Rd CedarA v C d right Dr Whitney La n e La Round A Rd Trevose Heights ny Valley R ay v d rook Linden i Dr i 311 300 Dekalb Pk e T e 80 f Meadow La S Pl m D Philadelphia, please use SEPTA's t 150 a Dr d Fawn V W Dr 80- arminster Rd E A Linden sh ally-Ho Rd W eser La o Elm Aintree Rd ay Ne n La s Somers Rd Rd S Poplar RdS Center Rd Delft La Jef v 3800 v r Horseshoe Mettler Princeton Rd Quail A A under C A Poquessing W n Mann Rd r Militia Hill Rd v rrest v ve m D p W UPPER Grasshopper La Prudential Rd lo r D Newington Lafayette A W S Lake Rd 1400 3rd S eldon v e Crestview ly o TURNPIKE A Neshaminy s o u Rd A Suburban Street and Transit Map. -

LHAT 40Th Anniversary National Conference July 17-20, 2016

Summer 2016 Vol. 39 No. 2 IN THE LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES LEAGUE LHAT 40th Anniversary National Conference 9 Newport Drive, Ste. 200 Forest Hill, MD 21050 July40th 17-20, ANNUAL 2016 (T) 443.640.1058 (F) 443.640.1031 WWW.LHAT.ORG CONFERENCE & THEATRE TOUR ©2016 LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES. Chicago, IL ~ JULY17-20, 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Greetings from Board Chair, Jeffery Gabel 2016 Board of Directors On behalf of your board of directors, welcome to Chicago and the L Dana Amendola eague of Historic American Theatres’ 40th Annual Conference Disney Theatrical Group and Theatre Tour. Our beautiful conference hotel is located in John Bell the heart of Chicago’s historic theatre district which has seen FROM it all from the rowdy heydays of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to Tampa Theatre Randy Cohen burlesque and speakeasies to the world-renowned Lyric Opera, Americans for the Arts Steppenwolf Theatre and Second City. John Darby The Shubert Organization, Inc. I want to extend an especially warm welcome to those of you Michael DiBlasi, ASTC who are attending your first LHAT conference. You will observe old PaPantntaggeses Theh attrer , LOL S ANANGGELEL S Schuler Shook Theatre Planners friends embracing as if this were some sort of family reunion. That’s COAST Molly Fortune because, for many, LHAT is a family whose members can’t wait Newberry Opera House to catch up since last time. It is a family that is always welcoming Jeffrey W. Gabel new faces with fresh ideas and even more colorful backstage Majestic Theater stories. -

527-7047 [email protected] Playbill: Venues

Playbill: Who We Are stablished in 1884, Playbill now serves theater in most major American cities. It is a staple for the performing arts for over four generations. PlaybillE is the connection between the performers and the audience offering informative and up-to-date editorial vital and specific for the particular performance. Playbill delivers to your targeted market through an unparalleled connection with performing arts patrons. From the moment they sit down until they leave with their Playbill in hand, the publication is an intricate and essential part of their evening. Playbill readers are affluent and educated. This highly sought-after market has proven to have exciting, active and involved lifestyles. This gives advertisers an opportunity to reach the most targeted audience in town. Michel Manzo - 610-527-7047 [email protected] Playbill: Venues Playbill is present in the most prestigious venues in each market. The audience you want to reach attends the Playbill performing arts venues including: VENUES SERVED NEW YORK WEST NEW ENGLAND Broadway Theatres: Los Angeles: Henry Fonda Theatre, The Wang Center for the Performing Arts: Ambassador, American Airlines, Atkinson, Pantages Theatre, Wilshire Theatre, The Wang Theatre and Shubert Theatre Barrymore, Belasco, Beaumont, Booth, Brentwood Theatre, Wadsworth Theatre (including all performances of the Boston Broadhurst, Broadway, Circle in the Square, San Diego: Playgoers Series: Ballet and Boston Lyric Opera), Cort, Freidman, Gershwin, Golden, Hayes, Civic Theater The Colonial Theatre, The Wilbur Theatre, Hilton, Hirschfeld, Imperial, Jacobs, Kerr, San Francisco: The San Francisco Opera House, The Charles Playhouse I & II, Longacre, Lunt-Fontanne, Lyceum, Symphony, Curran Theatre, The Stuart Street Playhouse Majestic, Marquis, Miller, Minskoff, Music Golden Gate Theatre, Orpheum Theatre Box, Nederlander, New Amsterdam, Tempe: Gammage Auditorium MID-ATLANTIC O’Neill, Palace, Rodgers, Schoenfeld, Las Vegas: Venetian Hotel, Palazzo Hotel Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Orchestra Shubert, Simon, St. -

N E W S R E L E a S E

N E W S R E L E A S E CONTACT: Katherine Blodgett phone: 215.893.1939 e-mail: [email protected] Alyssa Porambo phone: 215.893.3136 e-mail: [email protected] DRAFT 7/20/2015 4:10 PM FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: July 20, 2015 The Philadelphia Orchestra and The Kimmel Center Partner for FREE Neighborhood Concert in Verizon Hall and FREE Commonwealth Plaza Entertainment, July 30 from 4-8:30 PM Wells Fargo Presents Neighborhood Concert, conducted by Principal Guest Conductor Stéphane Denève Neighborhood Concert will be LiveNote ® enabled and streamed live at www.philorch.org FREE tickets may be reserved beginning July 21 at 10 AM at www.philorch.org (Philadelphia, July 20, 2015)—The Philadelphia Orchestra and The Kimmel Center partner for a free Neighborhood Concert presented by Wells Fargo, and free entertainment in Commonwealth Plaza on Thursday, July 30. Beginning at 4 PM on the Plaza Stage, Philadelphia area musical theater actors Jeff Coon and Fran Prisco will perform a medley of classic Broadway songs, accompanied by their music director, John Daniels. From 5 PM to 6 PM, Brazilian duo Minas will entertain audiences with their innovative sound, blending Brazilian guitar, jazz piano, and mixed vocals. Philadelphia Orchestra Principal Guest Conductor Stéphane Denève conducts the Neighborhood Concert, which begins at 6:30 PM in Verizon Hall. Immediately following the Orchestra’s Free Neighborhood Concert, from 7:30-8:30 p.m. there will be a performance by jazz singer Shakera Jones bringing the evening of diverse musical entertainment to a close. All activities are free but tickets are required for the Neighborhood Concert, and will be available on July 21 at 10 AM through the Orchestra’s website. -

Urban Arts Corps Records

MG 210 URBAN ARTS CORPS RECORDS The New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture 515 Malcolm X Boulevard New York, New York 10030 PREFACE This inventory was prepared as part of an archival preservation project to arrange, describe and catalog resources essential for the study of the African-American theater history. The necessary staff and supplies for the Blacks on stage: African-American Theater Arts Collection Project were made available through a combination of funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the City of New York. Table of Contents Preface i History ,. 1 Biography 3 Scope 4 container List.•.••......................... 5 Separation Record 10 URBAN ARTS CORPS, (1967- n.d.). RECORDS, 1955-1983. 6 archival boxes. (1.5 lin. ttl. History Urban Arts Corps (UAC) was founded in 1967 by Vinnette Carroll, who served as the company's premiere artistic director. It emerged as a pilot project of The Ghetto Arts Program, a program funded by the New York state Council on the Arts. Carroll established the UAC in response to a request from John B. Hightower, the executive director of the council. The initial members of the UAC were black and Puerto Rican students aged 17 through 22, from New York City pUblic schools and youth agencies. The objectives set forth by those creating the UAC were to: share their professional training; provide youth in ghetto areas with direct collaborative experiences with performing artists who shared their social and or cultural heritage; aid in the development of work techniques; introduce ghetto youth to materials, organizations, and artists that would enhance and improve their self image; stimulate and aid in the development of young artists in disadvantaged areas; and stimulate interest in professional and educational opportunities in the arts. -

The Glass Menagerie

2010-11 HOT Season for Young People Teacher Guidebook The Glass Menagerie Walnut Street Theatre PHOTO BY MARK GARVIN Tennessee Performing Arts Center TPAC Education is made possible in part by the generous contributions, sponsorships, and in-kind gifts from the following corporations, foundations, government agencies, and other organizations. AT&T Mapco Express/Delek US American Airlines Meharry Medical College The Atticus Trust The Memorial Foundation Bank of America Metropolitan Nashville Airport Baulch Family Foundation Authority BMI Miller & Martin, PLLC Bridgestone Americas Trust Fund Morton’s,The Steakhouse, Brown-Forman Nashville Cal IV Entertainment Nashville Predators Foundation Caterpillar Financial Services National Endowment for the Arts Corporation Nissan North America, Inc. Central Parking Corporation NovaCopy Coca-Cola Bottling Co. Piedmont Natural Gas Foundation The Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee Pinnacle Financial Partners Corrections Corporation The Premiere Event HOT Transportation grants underwritten by of America Publix Super Markets Charities The Danner Foundation Mary C. Ragland Foundation Davis-Kidd Booksellers Inc. The Rechter Family Fund* The Dell Foundation Sheraton Nashville Downtown Dollar General Corporation South Arts Doubletree Hotel Downtown Irvin and Beverly Small Foundation This performance is Nashville presented through SunTrust Bank, Nashville Fidelity Offset, Inc. arrangements Earl Swensson Associates, Inc. made by Baylin Artists First Tennessee Bank Management. Target Samuel M. Fleming -

Beautiful – the Carole King Musical Will Return to Philadelphia at the Academy of Music January 8-20, 2019

Tweet it! .@Carole_King’s stunning Grammy-winning show @BeautifulOnBway returns to the Academy of Music from Jan 8-20! For more info and tickets visit kimmelcenter.org. #BeautifulOnBway Press Contacts: Lauren Woodard Lisa Jefferson 215-790-5835 267-765-3723 [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BROADWAY’S SMASH HIT BEAUTIFUL – THE CAROLE KING MUSICAL WILL RETURN TO PHILADELPHIA AT THE ACADEMY OF MUSIC JANUARY 8-20, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, November 15, 2018) –– Producers Paul Blake and Sony/ATV Music Publishing announce that the Tony & Grammy Award-winning Broadway hit Beautiful—The Carole King Musical, about the early life and career of the legendary and groundbreaking singer/songwriter, will make its return to Philadelphia at the Academy of Music for two weeks from Tuesday, January 8 – Sunday, January 20, 2019. At the time of its last run in Philadelphia, Beautiful was the Kimmel Center’s highest-grossing Broadway Philadelphia production ever. To purchase tickets, visit www.kimmelcenter.org, call (215) 893-1999, or visit the Kimmel Center Box Office. Ticket prices start at $20.00. “I am thrilled that Beautiful continues to delight and entertain audiences around the globe, in England, Japan and Australia and that we are entering our fourth amazing year of touring the U.S.,” producer Paul Blake said. “We are so grateful that over five million audience members have been entertained by our celebration of Carole's story and her timeless music.” For more information and a video sneak peek, please visit www.BeautifulOnBroadway.com. “Once again, the talented cast of Beautiful breathes new life into the cherished, sentimental saga of one of music’s leading heroines,” said Anne Ewers, President of the CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.