A Preliminary Survey of the Historic Plays and Players Theatre: Preservation Issues to Be Addressed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Play the Forrest Theatre for One Week Only As Part of Kimmel Center’S Broadway Philadelphia Season! Tuesday, February 13 - Sunday, February 18, 2018

Tweet it! Sugar… butter… flour… @WaitressMusical comes to the @KimmelCenter – 2/13-2/18! Visit kimmelcenter.org for more info. #WaitressMusical #BWYPHL Press Contacts: Monica Robinson Lisa Jefferson 215-790-5847 267-765-3723 [email protected] [email protected] TO PLAY THE FORREST THEATRE FOR ONE WEEK ONLY AS PART OF KIMMEL CENTER’S BROADWAY PHILADELPHIA SEASON! TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 13 - SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 18, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center and The Shubert Organization are thrilled to announce Waitress will play the Forrest Theatre for a limited one-week engagement from Tuesday, February 13 through Sunday, February 18, 2018. Brought to life by a groundbreaking all-female creative team, this irresistible new hit features original music and lyrics by 6-time Grammy® nominee Sara Bareilles ("Brave," "Love Song"), a book by acclaimed screenwriter Jessie Nelson (I Am Sam), choreography by Lorin Latarro (Les Dangereuse Liasons, Waiting For Godot) and direction by Tony Award® winner Diane Paulus (Hair, Pippin, Finding Neverland). “What an honor to have this incredibly heartwarming show make its Philadelphia debut as part of our 2017-18 Broadway Philadelphia season,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Brought to Broadway by a group of imaginative, strong women, this film-turned- musical tells the story of another strong woman forging her own path, something to which we all can relate.” Inspired by Adrienne Shelly's beloved film, Waitress tells the story of Jenna - a waitress and expert pie maker. Jenna dreams of a way out of her small town and loveless marriage. -

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance Edited by Kathy A. Perkins, Sandra L. Richards, Renée Alexander Craft , and Thomas F. DeFrantz First published 2009 ISBN 13: 978-1-138-72671-0 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-315-19122-5 (ebk) Chapter 20 Being Black on Stage and Screen Black actor training before Black Power and the rise of Stanislavski’s system Monica White Ndounou CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 124 125 Being Black on stage and screen Worth’s Museum, the All- Star Stock Company was the fi rst professional Black stock company and training school for African American performers (Peterson, “Profi les” 70– 71). Cole’s institution challenged popular perceptions of Black performers as “natural actors” 20 lacking intellect and artistry (Ross 239). Notable performers in the company demonstrated expertise in stage management, producing, directing, playwriting, songwriting, and musical composition. They did so while immersed in the study of voice and vocal music (i.e. opera); BEING BLACK ON STAGE movement through dance (i.e. the cakewalk); comedy, including stand-up and ensemble work in specialty acts (i.e. minstrelsy), and character acting. Examples of the performance styles AND SCREEN explored at the All- Star Stock Company include The Creole Show (1890–1897), the Octoroons Company (1895– 1900), the Black Patti Troubadours (1896– 1915), the Williams and Walker Company (1898– 1909), and the Pekin Stock Company (1906– 1911), which performed Black Black actor training before Black Power musicals and popular comedies (Peterson, “Directory” 13). Some of the Pekin’s players were and the rise of Stanislavski’s system also involved in fi lm, like William Foster, who is generally credited as the fi rst Black fi lm- maker ( The Railroad Porter , 1912) (Robinson 168–169). -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States. -

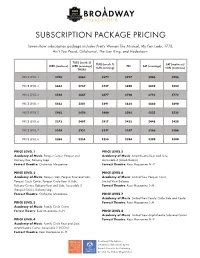

Subscription Package Pricing

2020 2021 SUBSCRIPTION PACKAGE PRICING Seven-show subscription package includes Pretty Woman The Musical, My Fair Lady, 1776, Ain’t Too Proud, Oklahoma!, The Lion King, and Hadestown. TUES (week 2) TUES (week 1) SAT (matinees) WED (matinee) WED (evenings) FRI SAT (evenings) SUN (evening) SUN (matinees) THURS PRICE LEVEL 1 $745 $862 $872 $927 $946 $956 PRICE LEVEL 2 $664 $737 $747 $800 $832 $852 PRICE LEVEL 3 $594 $667 $677 $720 $752 $772 PRICE LEVEL 4 $523 $581 $591 $634 $660 $690 PRICE LEVEL 5 $402 $450 $460 $503 $525 $535 PRICE LEVEL 6 $373 $407 $417 $433 $448 $458 PRICE LEVEL 7 $348 $331 $341 $357 $366 $366 PRICE LEVEL 8 $268 $258 $258 $284 $290 $300 PRICE LEVEL 1 PRICE LEVEL 5 Academy of Music: Parquet Center, Parquet and Academy of Music: Amphitheatre Rear and Side; Balcony Box, Balcony Loge Accessible 4 (Amphitheatre) Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P PRICE LEVEL 2 PRICE LEVEL 6 Academy of Music: Parquet Side, Parquet Rear and Side, Academy of Music: Limited View Parquet Circle, Parquet Circle Center, Parquet Circle Rear & Side, Limited View Balcony Balcony Center, Balcony Rear and Side, Accessible 2 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M (Parquet Circle), Balcony Loge Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine PRICE LEVEL 7 Academy of Music: Limited View Family Circle Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 3 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M Academy of Music: Family Circle Center Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H PRICE LEVEL 8 Academy of Music: Limited View Amphitheatre Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 4 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P Academy of Music: Family Circle Rear and Side; Amphitheatre Center, Accessible 3 (FCCIR) Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H Broadway Philadelphia is presented collaboratively by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization 2020 2021 ADD-ON PRICING Prices listed below are inclusive of ticketing fees, excluding the $4 per order fee. -

The Work of the Little Theatres

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART THREE PAGE Dramatic Contests.144 I. Play Tournaments.144 1. Little Theatre Groups .... 149 Conditions Eavoring the Rise of Tournaments.150 How Expenses Are Met . -153 Qualifications of Competing Groups 156 Arranging the Tournament Pro¬ gram 157 Setting the Tournament Stage 160 Persons Who J udge . 163 Methods of Judging . 164 The Prizes . 167 Social Features . 170 2. College Dramatic Societies 172 3. High School Clubs and Classes 174 Florida University Extension Con¬ tests .... 175 Southern College, Lakeland, Florida 178 Northeast Missouri State Teachers College.179 New York University . .179 Williams School, Ithaca, New York 179 University of North Dakota . .180 Pawtucket High School . .180 4. Miscellaneous Non-Dramatic Asso¬ ciations .181 New York Community Dramatics Contests.181 New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs.185 Dramatic Work Suitable for Chil¬ dren .187 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE II. Play-Writing Contests . 188 1. Little Theatre Groups . 189 2. Universities and Colleges . I9I 3. Miscellaneous Groups . • 194 PART FOUR Selected Bibliography for Amateur Workers IN THE Drama.196 General.196 Production.197 Stagecraft: Settings, Lighting, and so forth . 199 Costuming.201 Make-up.203 Acting.204 Playwriting.205 Puppetry and Pantomime.205 School Dramatics. 207 Religious Dramatics.208 Addresses OF Publishers.210 Index OF Authors.214 5 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Distribution of 789 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard of the Drama Magazine from October, 1925 through May, 1929, by Type of Organization . 22 2. Distribution by States of 1,000 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard from October, 1925 through June, 1931.25 3. -

USING the WOODMERE ART MUSEUM AS a CASE STUDY a Thesis Submitted To

THE ORIGIN, PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF REGIONAL ART MUSEUMS — USING THE WOODMERE ART MUSEUM AS A CASE STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS by Hua Zhang May 2021 Thesis Approvals: Linda Earle, Thesis Advisor, Art History Department James Merle Thomas, Second Reader, Art History Department ABSTRACT This paper uses the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia as a case study to examine the origins and institutional evolution of American regional art museums, identify some of the challenges they currently face, and the important civic and cultural roles they play in their communities. The chapter “Origins” provides a basic overview of Woodmere’s founding and history and considers how, within an American context, such museums eventually evolved from private galleries to publicly engaged nonprofit organizations over the course of the twentieth century as their missions, stakeholders, and audiences evolved. Like other regional art museums that demonstrate the same model, Woodmere’s regional identity and its focus on local art deepen the ties between itself and the community it serves and creates cultural resonances that make regional art museums an irreplaceable part of the American museum industry. However, small regional art museums face important challenges as their finances are more vulnerable, and they must deal with some of the same social, institutional, and ethical issues faced by larger public- facing institutions with a smaller pool of resources. The chapter “Present Challenges” looks at the need to develop sustainable management and financial structures and inclusive strategies to understand and build on audience relationships as a way to survive and grow. -

"A Study of Three Plays by Jean Genet: the Maids, the Balcony, the Blacks"

Shifting Paradigms in Culture: "A Study of Three Plays by Jean Genet: The Maids, The Balcony, The Blacks" Department of English and Modern European Languages Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi 2005 Payal Khanna The purpose of this dissertation is two fold. Firstly, it looks at the ways in which Genet's plays question the accepted social positions and point towards the need for a radical social change. Secondly, this dissertation also looks at Genet's understanding of theatre to underline the social contradictions through this medium. The thesis studies through a carefully worked out methodology the dynamic relationship between theatre and its viewers. This dissertation analyses the works of Genet to locate what have been identified in the argument as points of subversion. In this world of growing multiculturalism where terms like globalization have become a part of our daily life Genet's works are a case in point. Genet's plays are placed in a matrix that is positioned outside the margins of society from where they question the normative standards that govern social function. They create an alternative construct to interpret critically the normalizing tendency of society that actually glosses over the social contradictions. The thesis studies the features of both the constructs-that of society and the space outside it, and the relation that Genet's plays evolves between them. The propensity of a society that is divided both on the basis of class and gender is towards privileging groups that are powerful. Therefore the entire social rubric is structured in a way that takes into consideration the needs of such groups only. -

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change. -

Women of the Bible La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum 10-1984 Women of the Bible La Salle University Art Museum Daniel Burke F.S.C., Ph.D. La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum and Burke, Daniel F.S.C., Ph.D., "Women of the Bible" (1984). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 73. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/73 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I WOMEN OF THE BIBLE La Salle University Art Museum October 8th - November 30th, 1984 cover illustration: "Jael" by Jan Saenredam (1597-1665), Dutch Engraving Women of the Bible The Old Testament heroines depicted here in prints and paint ings were (with the exception, of course, of Bathsheba and Delilah) faithful and patriotic women of strong religious conviction. As wives, mothers, prophetesses, or soldiers, they raised new genera tions for the fledgling nation of Israel, provided good management and diplomacy in peace, inspiration and leadership in war. Their strength and courage were awesome, at times even barbaric. But it is clear, that for their contemporaries, their ends— to provide for the family, serve God and his people, build the nation of Israel against tremendous odds— justified their means, even though those might on occasion include assassination, seduction, or deceit. -

The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia 4-RC-21019 6-9-05

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD REGION FOUR CONCERTO SOLOISTS d/b/a THE CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF PHILADELPHIA1 Employer and Case 4–RC–21019 PHILADELPHIA MUSICIANS’ UNION LOCAL 77, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS, AFL-CIO2 Petitioner REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S DECISION AND DIRECTION OF ELECTION The Employer, The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, is a small, elite orchestra which performs at concerts and other engagements. The Petitioner, Philadelphia Musicians’ Union Local 77, has filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board under Section 9(c) of the National Labor Relations Act seeking to represent a unit of the Musicians who perform in the Chamber Orchestra. There are about 33 Musicians in the petitioned-for unit. The Employer contends that the Musicians are independent contractors and thus are excluded from the coverage of the Act. A hearing officer of the Board held a hearing, and the parties filed briefs. I have considered the evidence and the arguments presented by the parties, and as discussed below, I have concluded that the Musicians are statutory employees. Accordingly, I am directing an election in a bargaining unit of the Employer’s Musicians.3 To provide a context for my discussion, I will first present a brief overview of the Employer’s operations. Then, I will review the factors that must be evaluated in determining independent contractor status and present in detail the facts and reasoning that support my conclusion that the Musicians are statutory employees. 1 The Employer’s name was amended at the hearing. 2 The Petitioner’s name was amended at the hearing. -

Nashville Community Theatre: from the Little Theatre Guild

NASHVILLE COMMUNITY THEATRE: FROM THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD TO THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE A THESIS IN Theatre History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri – Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by ANDREA ANDERSON B.A., Trevecca Nazarene University, 2003 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 ANDREA JANE ANDERSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LITTLE THEATRE MOVEMENT IN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE: THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD AND THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE Andrea Jane Anderson, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In the early 20th century the Little Theatre Movement swept through the United States. Theatre enthusiasts in cities and towns across the country sought to raise the standards of theatrical productions by creating quality volunteer-driven theatre companies that not only entertained, but also became an integral part of the local community. This paper focuses on two such groups in the city of Nashville, Tennessee: the Little Theatre Guild of Nashville (later the Nashville Little Theatre) and the Nashville Community Playhouse. Both groups shared ties to the national movement and showed a dedication for producing the most current and relevant plays of the day. In this paper the formation, activities, and closure of both groups are discussed as well as their impact on the current generation of theatre artists. iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, have examined a thesis titled “Nashville Community Theatre: From the Little Theatre Guild to the Nashville Community Playhouse,” presented by Andrea Jane Anderson, candidate for the Master of Arts degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

Septa-Phila-Transit-Street-Map.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q v A Mill Rd Cricket Kings Florence P Kentner v Jay St Linden Carpenter Ho Cir eb R v Newington Dr Danielle Winding W Eagle Rd Glen Echo Rd B Ruth St W Rosewood Hazel Oak Dr Orchard Dr w For additional information on streets and b v o o r Sandpiper Rd A Rose St oodbine1500 e l Rock Road A Surrey La n F Cypress e Dr r. A u Dr Dr 24 to Willard Dr D 400 1 120 ant A 3900 ood n 000 v L v A G Norristown Rd t Ivystream Rd Casey ie ae er Irving Pl 0 Beachwoo v A Pine St y La D Mill Rd A v Gwynedd p La a Office Complex A Rd Br W Valley Atkinson 311 v e d 276 Cir Rd W A v Wood y Mall Milford s r Cir Revere A transit services ouside the City of 311 La ay eas V View Dr y Robin Magnolia R Daman Dr aycross Rd v v Boston k a Bethlehem Pike Rock Rd A Meyer Jasper Heights La v 58 e lle H La e 5 Hatboro v Somers Dr v Lindberg Oak Rd A re Overb y i t A ld La Rd A t St ll Wheatfield Cir 5 Lantern Moore Rd La Forge ferson Dr St HoovStreet Rd CedarA v C d right Dr Whitney La n e La Round A Rd Trevose Heights ny Valley R ay v d rook Linden i Dr i 311 300 Dekalb Pk e T e 80 f Meadow La S Pl m D Philadelphia, please use SEPTA's t 150 a Dr d Fawn V W Dr 80- arminster Rd E A Linden sh ally-Ho Rd W eser La o Elm Aintree Rd ay Ne n La s Somers Rd Rd S Poplar RdS Center Rd Delft La Jef v 3800 v r Horseshoe Mettler Princeton Rd Quail A A under C A Poquessing W n Mann Rd r Militia Hill Rd v rrest v ve m D p W UPPER Grasshopper La Prudential Rd lo r D Newington Lafayette A W S Lake Rd 1400 3rd S eldon v e Crestview ly o TURNPIKE A Neshaminy s o u Rd A Suburban Street and Transit Map.