Julia DYSON the Oleaster at the End of the Aeneid the Aeneid's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

00010853-Preview.Pdf

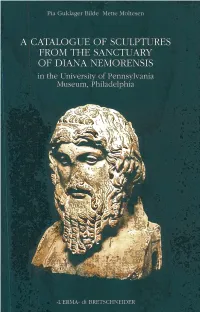

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-05-07 The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry Waters, Alison Waters, A. (2013). The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28172 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/705 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry by Alison Ferguson Waters A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY 2013 © Alison Ferguson Waters 2013 ii Abstract This study concerns the figure of Lucretia as she is presented by the Roman historian Livy in the first book of Ab Urbe Condita, where she is intended as an example of virtue, particularly in terms of her attention to woolworking. To find evidence for this ideal and how it was regarded at the time, in this study a survey is made of woolworking references in the contemporary Augustan poets Vergil, Tibullus, Propertius and Ovid. Other extant versions of the Lucretia legend do not mention woolworking; Livy appears to have added Lucretia’s devotion to wool, a tradition in keeping with Augustan propaganda. -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

The Wolf in Virgil Lee Fratantuono

The Wolf in Virgil Lee Fratantuono To cite this version: Lee Fratantuono. The Wolf in Virgil. Revue des études anciennes, Revue des études anciennes, Université Bordeaux Montaigne, 2018, 120 (1), pp.101-120. hal-01944509 HAL Id: hal-01944509 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01944509 Submitted on 23 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright ISSN 0035-2004 REVUE DES ÉTUDES ANCIENNES TOME 120, 2018 N°1 SOMMAIRE ARTICLES : Milagros NAVARRO CABALLERO, María del Rosario HERNANDO SOBRINO, À l’ombre de Mommsen : retour sur la donation alimentaire de Fabia H[---]la................................................................... 3 Michele BELLOMO, La (pro)dittatura di Quinto Fabio Massimo (217 a.C.): a proposito di alcune ipotesi recenti ................................................................................................................................ 37 Massimo BLASI, La consecratio manquée de L. Cornelius Sulla Felix ......................................... 57 Sophie HULOT, César génocidaire ? Le massacre des -

Further Commentary Notes

Virgil Aeneid X Further Commentary Notes Servius, the author of a fourth-century CE commentary on Virgil is mentioned several times. Servius based his notes extensively on the lost commentary composed earlier in the century by Aelius Donatus. A version of Servius, amplified by material apparently taken straight from Donatus, was compiled later, probably in the seventh or eighth century. It was published in 1600 by Pierre Daniel and is variously referred to as Servius Auctus, Servius Danielis, or DServius. Cross-reference may be made to language notes – these are in the printed book. An asterisk against a word means that it is a term explained in ‘Introduction, Style’ in the printed book. A tilde means that the term is explained in ‘Introduction, Metre’ in the printed book. 215 – 6 In epic, descriptions of the time of day, particularly dawn, call forth sometimes surprising poetic flights. In Homer these are recycled as formulae; not so in Virgil (for the most part), although here he is adapting a passage from an earlier first- century epic poet Egnatius, from whose depiction of dawn seems to come the phrase curru noctivago (cited in Macrobius, Sat. 6.5.12). This is the middle of the night following Aeneas’s trip to Caere. The chronology of Books VIII – X is as follows: TWO DAYS AGO Aeneas sails up the Tiber to Evander (VIII). NIGHT BEFORE Aeneas with Evander. Venus and Vulcan (VIII). Nisus and Euryalus (IX). DAY BEFORE Evander sends Aeneas on to Caere; Aneneas receives his armour (VIII). Turnus attacks the Trojan camp (IX, X). -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

Of Turnus in the Aeneid Michael Kelley

Tricks and Treaties: The “Trojanification” of Turnus in the Aeneid Michael Kelley, ‘18 In a poem characterized in large part by human intercourse with the divine, one of the most enigmatic augury passages of Virgil’s Aeneid occurs in Book XII, in which Juturna delivers an omen to incite the Latins toward breaking their treaty with the Trojans. The augury passage is, at a superficial level, a deceptive exhortation addressed to the Latins, but on a meta- textual, intra-textual, and inter-textual level, a foreshadowing of the downfall of Turnus and the Latins. In this paper, I will begin by illustrating how the deception within Juturna’s rhetoric and linguistic allusions to deception in the eagle apparition indicate a true meaning which supersedes Juturna’s intended trickery. Then, in demonstrating inter-textual and intra-textual paradigms for Turnus, I will explain how the omen, and the associations called for therein, actually anticipate Turnus’s impending, sacrificial death. Finally, I will address the implications of my claim, presenting an interpretation of a sympathetic Turnus and a pathetically deceived Juturna. While the omen which follows is not necessarily false, Juturna’s rhetoric, spoken in the guise of Turnus’s charioteer Metiscus,1 is marked by several rhetorical techniques that are, ultimately, fruitful in inciting the Latins toward combat. Attempting to invoke their better reason, Juturna begins the speech with several rhetorical questions that appeal to their sense of honor and their devotion to Turnus.2 Her description of the Trojans as a fatalis manus, translated by Tarrant as “a troop protected by fate,”3 is most likely sarcastic, referencing what she deems a self-important insistence on prophecy from the Trojans. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy’ 2016 Jillian Mitchell For Michael – and in memory of my father Kenneth who started it all Abstract for PhD Thesis in Classics The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus This thesis explores the last decades of legal paganism in the Roman Empire of the second half of the fourth century CE through the eyes of Symmachus, orator, senator and one of the most prominent of the pagans of this period living in Rome. It is a religious biography of Symmachus himself, but it also considers him as a representative of the group of aristocratic pagans who still adhered to the traditional cults of Rome at a time when the influence of Christianity was becoming ever stronger, the court was firmly Christian and the aristocracy was converting in increasingly greater numbers. Symmachus, though long known as a representative of this group, has only very recently been investigated thoroughly. Traditionally he was regarded as a follower of the ancient cults only for show rather than because of genuine religious beliefs. I challenge this view and attempt in the thesis to establish what were his religious feelings. Symmachus has left us a tremendous primary resource of over nine hundred of his personal and official letters, most of which have never been translated into English. These letters are the core material for my work. I have translated into English some of his letters for the first time. -

Ancient Legends of Roman History

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Castelli Romani” (Roman Castles) Are a Group of Towns in the Province of Rome

EUROPE ITALY GENZANO DI ROMA LAZIO The “Castelli Romani” (Roman Castles) are a group of towns in the province of Rome. The area of the “Castelli” occupies a volcanic and fertile area characterized by ancient settlements and flourishing agriculture. The old crater is now occupied by two lakes, Lake Nemi and Lake Albano. The recent name Roman Castles derives from the villages built around some villas and palaces where rich noble families spent the summer. The “Castelli Romani” are: •Albano Laziale •Ariccia •Castel Gandolfo •Colonna •Frascati •Genzano di Roma •Grottaferrata •Lanuvio •Lariano •Marino •Monte Compatri •Monte Porzio Catone •Nemi •Rocca di Papa •Rocca Priora •Velletri EVENTS “CASTELLI ROMANI” PARK HISTORICAL GEOLOGICAL INFORMATION INFORMATION UPPER SECONDARY SCHOOL: LICEO SCIENTIFICO “GIOVANNI VAILATI” ““CASTELLICASTELLI ROMANIROMANI”” REGIONALREGIONAL PARKPARK Genzano and its surroundings are included in the area of the “Castelli Romani” Regional Park . The chestnut is the most important tree in our area. The holm-oak tree is very important, too. Genzano’s events Here’s a short guide that makes you discover Genzano’s traditions. The “Infiorata” The most important attraction is the “Infiorata”, a folkloristic and religious exhibition known all over the world. The “Infiorata” has taken place on Sunday following Corpus Domini since 1778. It consists of a huge flower carpet divided into many images that covers the street that joins the cathedral with the main square. Many famous artists have contributed to the “Infiorata”. A masked parade walk on the flower carpet. The people wear traditional clothes that date back to the 17th century. At least 350,000 flower petals, in addition to earth, beans and sometimes wood cuttings, are necessary to make the carpet. -

Temples with Transverse Cellae in Republican and Early Imperial Italy

BABesch 82 (2007, 333-346. doi: 10.2143/BAB.82.2.2020781) Forms of Cult? Temples with transverse cellae in Republican and early Imperial Italy Benjamin D. Rous Abstract This article presents an analysis of a particular temple type that first appeared during the Late Republic, the temple with transverse cella. In the past this particular cella-form has been interpreted as a solution to spatial constraints. In more recent times it has been argued that the cult associated with the temple was the decisive factor in the adoption of the transverse cella. Neither theory, when considered in isolation, can fully and con- vincingly explain the particular forms of both Republican and Imperial temples. Rather, it can be argued that a combination of pragmatic and above all aesthetic considerations has played a major role in the particular archi- tecture of these temples.* INTRODUCTION archaeological evidence, even though the remains of the building itself have never been excavated. In the fourth book of his famous treatise on archi- Furthermore, this is one of the temples actually tecture, Vitruvius mentions a specific temple-type, mentioned by Vitruvius in his treatise. In yet an- whose basic characteristic is that all the features other case, the temple of Aesculapius in the Latin normally found on the short side of the temple colony of Fregellae, although construction activi- have been transferred to the long side. What this ties have destroyed virtually the entire temple basically means is that the pronaos still constitutes building, a reconstruction of a transverse cella the front part of the temple, but instead of being nevertheless seems likely on the basis of the scant longitudinally developed, the cella is rotated 90º remains we do have.