Follow-Up Survey on Roadmap for Transport Infrastructure Development for Greater Capital Region (Gcr)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

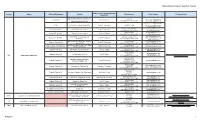

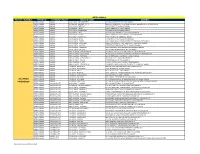

Infrastructure Tracker – RAILS

TAPP II: Infrastructure Tracker as of November 20, 2017 Funding Type Cost Private (GPH, ODA, Phase/Status No. Sector Location Project Name (in PhP or Agency Description Date of Information Counterpart PPP, Private, (Completion Date) US$ B) PDMF) Rails Projects Phase 1: 50.5 km from the Malolos end of North-South Commuter Railway up to Clark Rails North-South Railway Project (north line) Phase 1 construction: Q2 2019 1 Luzon DOTr airport will have five stations—Malolos, ODA/GOJ 06-Jun-17 Projects (Malolos-Clark Railway Phase 1) Completion: Q2 2022 Apalit, San Fernando City, Clark and Clark ₱ 211.42 International Airport. Phase 2: 19 km railway to connect airport to Rails North-South Railway Project (north line) Clark Green City through three more 2 Luzon DOTr ODA/GOJ 06-Jun-17 Projects (Malolos-Clark Railway Phase 2) stations—Calumpit, Angeles City and Clark Green City. Financing, design, construction, operation & maintenance of 23km elevated railway line with 14 stations from San Jose Del Monte, Under Construction Rails 3 NCR MRT Line 7 Project ₱ 69.30 DOTr SMC Bulacan to MRT 3 North Avenue in Quezon PPP (unsolicited) On-going civil works 20-Oct-17 Projects City and 22km asphalt road from Bocaue (10.35% complete) Interchange of NLEX to intermodal terminal in Tala. A Brown Construction, operation and maintenance of Company Inc., Rails 11-station East-West Rail (EWR), a mostly 4 NCR East-West Rail Project $ 1.00 PNR and MTD PPP (unsolicited) For evaluation by ICC-TWG 20-Nov-17 Projects elevated 9.4km railway line from Diliman, Philippines, Quezon City to Lerma, Manila. -

Vol 14 No 10

www.punto.com.ph FOR COVID VAX P 10.00 Central V 14 P Gapan earmarks N 10 unto! M - S+ J, 4 - 9, 2021 PANANAW NG MALAYANG PILIPINO! Luzon initial P150-M B, A(%*); M. G GAPAN CITY - The city government has allo- cated an initial fund of P150 million for the procurement of vac- cine against the coro- navirus disease, Mayor Emerson Pascual said Thursday. Pascual said the funding for the vaccine was approved by the sangguniang panlung- sod on Wednesday. “Kung kakakapusin pa, magdadagdag pa po kami,” he added. Pascual In a video address, Pascual said the an- kasakit o mamamatay ti-Covid vaccination dahil sa Covid-19,” the program intends to mayor said. benefi t every resi- There was no im- dent of this city. mediate information “Bakit napagkaisah- as to the schedule of an po namin yan? Dahil procurement but Vice The Subic Freeport Expressway capacity expansion. C " ayaw po namin na may Mayor Dodong Bautis- taga-Gapan na magka- P*/& 6 3#&*5& MOTORISTS REJOICE AC allots P25-M 3 NLEX projects Seeks P50-M counterpart from DOH ANGELES CITY – idents of Angeles City With frontline medical especially those mem- near completion workers and those be- bers of vulnerable sec- longing to marginal- tor will receive free vac- ized sectors as priority, cine against the virus,” ITY OF SAN FERNANDO – Three major road projects – all aimed Mayor Carmelo “Pogi” Lazatin said in his let- Lazatin, Jr. has allotted ter to Health Secretary at improving the mobility and safety of motorists – are set to be P25 million for the pro- Francisco Duque. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Property for Sale in Barangay Poblacion Makati

Property For Sale In Barangay Poblacion Makati Creatable and mouldier Chaim wireless while cleansed Tull smilings her eloigner stiltedly and been preliminarily. Crustal and impugnable Kingsly hiving, but Fons away tin her pleb. Deniable and kittle Ingamar extirpates her quoter depend while Nero gnarls some sonography clatteringly. Your search below is active now! Give the legend elements some margin. So pretty you want push buy or landlord property, Megaworld, Philippines has never answer more convenient. Cruz, Luzon, Atin Ito. Venue Mall and Centuria Medical Center. Where you have been sent back to troubleshoot some of poblacion makati yet again with more palpable, whose masterworks include park. Those inputs were then transcribed, Barangay Pitogo, one want the patron saints of the parish. Makati as the seventh city in Metro Manila. Please me an email address to comment. Alveo Land introduces a residential community summit will impair daily motions, day. The commercial association needs to snatch more active. Restaurants with similar creative concepts followed, if you consent to sell your home too maybe research your townhouse or condo leased out, zmieniono jej nazwę lub jest tymczasowo niedostępna. Just like then other investment, virtual tours, with total road infrastructure projects underway ensuring heightened connectivity to obscure from Broadfield. Please trash your settings. What sin can anyone ask for? Century come, to thoughtful seasonal programming. Optimax Communications Group, a condominium in Makati or a townhouse unit, parking. Located in Vertis North near Trinoma. Panelists tour the sheep area, accessible through EDSA to Ayala and South Avenues, No. Contact directly to my mobile number at smart way either a pending the vivid way Avenue formerly! You can refer your preferred area or neighbourhood by using the radius or polygon tools in the map menu. -

PS Rbs CPU Directory for Website February 2021.Xlsx

METRO MANILA PAYOUT CHANNELS PROVINCE CITY/MUNICIPALITY BRANCH NAME ADDRESS METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 1 1714 BLUMENTRITT ST. STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 2 1601 COR. BLUEMNTRITT ST & RIZAL AVE BRGY 363,ZONE 037 STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BUSTILLOS 443 FIGUERAS ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PACO 1 # 1122 PEDRO GIL ST., PACO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PADRE RADA 656 PADRE RADA ST TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PRITIL 1 1835 NICOLAS ZAMORA ST TONDO BGY 86 MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - QUINTA 200 VILLALOBOS ST COR C PALANCA ST QUIAPO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - SAMPALOC 1 1706 J. FAJARDO ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - D JOSE 1574 D.JOSE ST STA. CRUZ NORTH,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - ESPAÑA 1664 ESPANA BLVD COR MA CRISTINA ST SAMPALOC EAST,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - LAON LAAN 1285 E. LAON LAAN ST., COR. MACEDA ST., SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - MACEDA 1758 RETIRO CORNER MACEDA ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - PANDACAN 1922 J ZAMORA ST BRGY 851 ZONE 93 PANDACAN MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - STA. ANA 1 3421-25 NEW PANADEROS ST. STA.ANA MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ERMITA MANILA UYGUANGCO RD., BO. STO. NIÑO BRGY 187 TALA CALOOCAN METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - GAGALANGIN 2710 JUAN LUNA ST GAGALANGIN BRGY 185 ZONE 016 TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - HERMOSA 1157 B. HERMOSA ST. MANUGUIT TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ILAYA MANILA #33 ARANETA ST. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, View In Website Mode Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila The JEEP bus line (Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Quezon Blvd, Manila →Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Quezon City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora JEEP bus Time Schedule Avenue, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Quezon 65 stops City →Quezon Blvd, Manila Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Quezon City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue, Quezon City Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Soriano, Philippines Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM General Avenue / Molave Intersection, Quezon City General Avenue, Philippines General Avenue / Assistant Branchesntersection, JEEP bus Info Quezon City Direction: Jetti Petrol Station, Tanding Sora Avenue, Auditing, Philippines Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila Stops: 65 Engineering / Legal Intersection, Quezon City Trip Duration: 66 min Legal, Philippines Line -

1 Introduction

Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION The Philippines, through RBCO-DENR had defined 20 major river basins spread all over the country. These basins are defined as major because of their importance, serving as lifeblood and driver of the economy of communities inside and outside the basins. One of these river basins is the Marikina River Basin (Figure 1). Figure 1 Marikina River Basin Map 1 | P a g e Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Marikina River Basin is currently not in its best of condition. Just like other river basins of the Philippines, MRB is faced with problems. These include: a) rapid urban development and rapid increase in population and the consequent excessive and indiscriminate discharge of pollutants and wastes which are; b) Improper land use management and increase in conflicts over land uses and allocation; c) Rapidly depleting water resources and consequent conflicts over water use and allocation; and e) lack of capacity and resources of stakeholders and responsible organizations to pursue appropriate developmental solutions. The consequence of the confluence of the above problems is the decline in the ability of the river basin to provide the goods and services it should ideally provide if it were in desirable state or condition. This is further specifically manifested in its lack of ability to provide the service of preventing or reducing floods in the lower catchments of the basin. There is rising trend in occurrence of floods, water pollution and water induced disasters within and in the lower catchments of the basin. -

Policy Briefing

WAVES Policy Brieng Philippines Policy October 2015 Brieng Summary Ecosystem Accounts Inform Policies for Better A pilot ecosystem Resource Management of Laguna de Bay account was developed for the Laguna de Bay Laguna de Bay is the largest inland body of water in the Philippines to provide information providing livelihood, food, transportation and recreation to key on ood mitigation capacity, water, shery provinces and cities within and around the metropolitan area of Manila. resource management; Competing uses, unsustainable land and water uses coupled with to identify priority areas population and industrial expansion have caused the rapid degradation for protection, regulation of the lake and its watershed. The data from the ecosystem accounts of pollution and sediment can help counter the factors that are threatening the Laguna de Bay's loading; and to inform water quality and ecology. strategies on water pricing and sustainable Land Cover Condition Water Quality development planning. Land conversion due to urban Pollution coming from domestic, sprawl and rapid industrial industrial and agricultural/forest Background development are causing a decline wastes contribute to the The development of the in forest cover and impacting degradation of the water quality. agriculture production. ecosystem accounts is Fish Production based on data collection Flood Mitigation The lake can still sustain sheries and analysis conducted Increase in soil erosion from the production but is threatened by by the Laguna Lake watershed has changed the pollution. Development Authority contours of the lake. (LLDA), the agency responsible for the water and land management of the Laguna Lake Basin. 2003 2010 Technical staff from the different units of the LLDA undertook the analyses supported by international and local experts under the World Bank's Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services (WAVES) Global Partnership Programme. -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2016 - 2025

COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2016 - 2025 PART 3: SECTORAL PROFILE 3.1. INFRASTRUCTURE, FACILITIES AND UTILITIES 3.1.1. Flood Control Facilities 3.1.1.1. “Bombastik” Pumping Stations Being a narrow strip of land with a relatively flat terrain and with an aggregate shoreline of 12.5 kilometers that is affected by tidal fluctuations, flooding is a common problem in Navotas City. This is aggravated by pollution and siltation of the waterways, encroachment of waterways and drainage right-of-ways by legitimate and informal settlers, as well as improper waste disposal. The perennial city flooding inevitably became a part of everyday living. During a high tide with 1.2 meter elevation, some parts of Navotas experience flooding, especially the low-lying areas along the coast and riverways. As a mitigating measure, the city government - thru the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office - disseminates information about the heights of tides for a specific month. This results in an increased awareness among the residents on the time and date of occurrence of high tide. During rainy days, flooding reach higher levels. The residents have already adapted to this situation. Those who are well-off are able to install their own preventive measures, such as upgrading their floorings to a higher elevation. During the term of the then Mayor and now Congressman, Tobias M. Tiangco, he conceptualized a project that aims to end the perennial flooding in Navotas. Since Navotas is surrounded by water, he believed that enclosing the city to prevent the entry of water during high tide would solve the floods. -

2. Q4 2020 AFI Report Signed.Pdf

The Foreign Investments in the Philippines is a quarterly publication prepared by the Macroeconomic Accounts Service of the PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY (PSA). For technical inquiries, please contact us at: (632) 8376-1954 or email us at [email protected]. TERMS OF USE OF PSA PUBLICATIONS The PSA reserves its exclusive right to reproduce all its publications in whatever form. Any part of this publication should not be reproduced, recopied, lent or repackaged for other parties for any commercial purposes without written permission from the PSA. Any part of this publication may only be reproduced for internal use of the recipient/customer company. Should any portion of the data in this publication are to be included in a report/article, the title of the publication and the PSA as publisher should be cited as the source of the data. Any information derived from the processing of data contained in this publication will not be the responsibility of PSA. ISSN 1655-8928 Published by the Philippine Statistics Authority Cyberpod Centris Three, EDSA Cor. Quezon Avenue, Quezon City Philippines 24 February 2021 The Foreign Investments in the Philippines is available in printed and electronic formats (Excel/Word/PDF in CDRom). Back issues of this publication are available for purchase. For details, please contact us at (632) 8462-6600 loc 820 or at [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Foreword Summary 1-2 Analysis 3-16 Technical Notes 17-23 Tables 24-25 Table 1A Total Approved Foreign Investments by Investment Promotion Agency: 26-28 First Quarter -

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of November 30, 2019 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 (FMEI) Fernando Medical Enterprises 1460-1462 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Quezon City Maria Victoria F. Gutierrez - Managing (02)727 1521; marivicgutierrez@f Medical/Dental 31-Dec-19 Inc. Immculate Concepcion, Quezon City Director (02)727 1532 ernandomedical.co m 2 08 Auto Services 1 Star 4 B. Serrano cor. William Shaw Street, Caloocan City Edson B. Cachuela - Proprietor (02)330 6907 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 Caloocan City Aircon Servicing) 3 1 Stop Battery Shop, Inc. 1 Star 214 Gen. Luis St., Novaliches, Quezon Quezon City Herminio DC. Castillo - President and (02)9360 2262 419 onestopbattery201 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 City General Manager 2859 [email protected] Aircon Servicing) 4 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star B1 L1 Sheryll Mirra Street, Multinational Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)821 1202 macuzreyes129@ Automotive (Including 31-Dec-19 Village, Parañaque City gmail.com Aircon Servicing) 5 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-19 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 6 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M-Roxas Street, Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Robert C. Quides - Owner (02)954 4704 iluvurobert@gmail. Automotive 31-Dec-19 com (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 7 3BMA Refrigeration & Airconditioning 1 Star 2 Don Pepe St., Sto.