September 2018 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Development Center Opens in Durant

A Choctaw The 5 Tribes 6th veteran value Storytelling Annual tells his of hard Conference Pow Wow story work to be held Page 5 Page 7 Page 10 Page 14 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma November 2010 Issue Serving 203,830 Choctaws Worldwide Choctaws ... growing with pride, hope and success Tribal Council holds October Child Development Center opens in Durant regular session By LARISSA COPELAND The Choctaw Nation Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Tribal Council met on A ribboncutting was held Oct. 9 in regular session at the new state-of-the-art at Tushka Homma. Trib- Choctaw Nation Child De- al Council Speaker Del- velopment Center in Durant ton Cox called the meet- on Oct. 19, marking the end ing to order, welcomed of five years of preparation, guests and then asked for construction and hard work, committee reports. After and the beginning of learn- committee reports were ing, laughter and growth at given the Tribal Council the center. addressed new business. On hand for the cer- •Approval of sev- emony was Choctaw Chief eral budgets including: Gregory E. Pyle, Assistant Upward Bound Math/ Chief Gary Batton, Chicka- Science Program FY saw Nation Governor Bill 2011, DHHS Center for Anoatubby, U.S. Congress- Medicare and Medicaid man Dan Boren, Senator Services Center for Med- Jay Paul Gumm, Durant icaid and State Opera- Mayor Jerry Tomlinson, tions Children’s Health Chief Gregory E. Pyle, Assistant Chief Gary Batton, and a host of tribal, state and local dignitaries cut the rib- Durant City Manager James Insurance Program bon at the new Child Development Center in Durant. -

From Scouts to Soldiers: the Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2013 From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945 James C. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Walker, James C., "From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 860. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/860 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM SCOUTS TO SOLDIERS: THE EVOLUTION OF INDIAN ROLES IN THE U.S. MILITARY, 1860-1945 by JAMES C. WALKER ABSTRACT The eighty-six years from 1860-1945 was a momentous one in American Indian history. During this period, the United States fully settled the western portion of the continent. As time went on, the United States ceased its wars against Indian tribes and began to deal with them as potential parts of American society. Within the military, this can be seen in the gradual change in Indian roles from mostly ad hoc forces of scouts and home guards to regular soldiers whose recruitment was as much a part of the United States’ war plans as that of any other group. -

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture by James Sandy, M.A. A Dissertation In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTORATE IN PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Dr. Aliza Wong Mark Sheridan, PhD. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James A. Sandy, May 2016 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way from raw idea to thesis to completed dissertation. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my career. Dr. Aliza Wong expanded my mind and horizons during a summer session course on Cultural Theory, which inspired a great deal of the theoretical framework of this work. As a co-chair of my committee, Dr. Barton Myers pushed both the project and myself further and harder than anyone else. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength and defining characteristic. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone, and for always providing the firmest yet most encouraging feedback. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic Contributions to American History.A Supplementary Booklet, Grades 4-12. INSTITUTION Caddo Parish School Board, Shreveport, La. NOTE' 57p.; For related document, see SP 009 719 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$3.32 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Achievement; *American History; *Cultural Background; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Groups; *Ethnic Origins; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Multicultural Education ABSTRACT This booklet is designed as a teacher guide for supplementary use in the rsgulat social studies program. It lists names and contributions of Americans from all ethnic groups to the development of the United States. Seven units usable at three levels (upper elementary, junior high, and high school) have been developed, with the material arranged in outline form. These seven units are (1) Exploration and Colonization;(2) The Revolutionary Period and Its Aftermath;(3) Sectionalism, Civil War, and Reconstruction;(4) The United States Becomes a World Power; (5) World War I--World War II; (6) Challenges of a Transitional Era; and (7) America's Involvement in Cultural Affairs. Bibliographical references are included at the end of each unit, and other source materials are recommended. (Author/BD) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * via the ERIC Document-Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the qUa_lity of the original document. Reproductions * supplied-by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. -

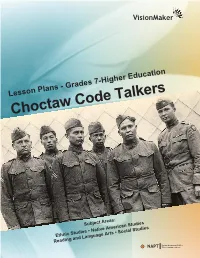

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI and WWII

They Served They Sacrificed Telephone Warriors Choctaw Code Talkers Soldiers who used their native language as a weapon against the enemy, making a marked difference in the outcome of World War I Telephone Warriors - beginning the weapon of words Among the Choctaw warriors of WWI were fifteen members of the 142nd Infantry Regiment, a member of the 143rd and two members of the 141st Infantry Regiment who are now heralded as “WWI Choctaw Code Talkers.” All Regiments were part of the 36th Division. The Code Talkers from the 142nd were: Solomon Bond Lewis; Mitchell Bobb; Robert Taylor; Calvin Wilson; Pete Maytubby; James M. Edwards; Jeff Nelson; Tobias William Frazier; Benjamin W. Hampton; Albert Billy; Walter Veach; Joseph Davenport; George Davenport; Noel Johnson; and Ben Colbert. The member of the 143rd was Victor Brown and the Choctaw Code Talkers in the 141st were Ben Carterby and Joseph Okla- hombi. Otis Leader served in the 1sr Division, 16th Infantry. All of these soldiers came together in WWI in France in October and November of 1918 to fight as a unified force against the enemy. On October 1, 1917, the 142nd was organized as regular infantry and given training at Camp Bowie near Fort Worth as part of the 36th Division. Transferred to France for action, the first unit of the division arrived in France, May 31, 1918, and the last August 12, 1918. The 36th Division moved to the western front on October 6, 1918. Although the American forces were late in entering the war that had begun in 1914, their participation provided the margin of victory as the war came to the end. -

'Choctaw: a Cultural Awakening' Book Launch Held Over 18 Years Old?

Durant Appreciation Cultural trash dinner for meetings in clean up James Frazier Amarillo and Albuquerque Page 5 Page 6 Page 20 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma May 2013 Issue Tribal Council meets in regular April session Choctaw Days The Choctaw Nation Tribal Council met in regular session on April 13 at Tvshka Homma. Council members voted to: • Approve Tribal Transporta- returning to tion Program Agreement with U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs • Approve application for Transitional Housing Assis- tance Smithsonian • Approve application for the By LISA REED Agenda Support for Expectant and Par- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma 10:30 a.m. enting Teens, Women, Fathers Princesses – The Lord’s Prayer in sign language and their Families Choctaw Days is returning to the Smithsonian’s Choctaw Social Dancing • Approve application for the National Museum of the American Indian in Flutist Presley Byington Washington, D.C., for its third straight year. The Historian Olin Williams – Stickball Social and Economic Develop- Dr. Ian Thompson – History of Choctaw Food ment Strategies Grant event, scheduled for June 21-22, will provide a 1 p.m. • Approve funds and budget Choctaw Nation cultural experience for thou- Princesses – Four Directions Ceremony for assets for Independence sands of visitors. Choctaw Social Dancing “We find Choctaw Days to be just as rewarding Flutist Presley Byington Grant Program (CAB2) Soloist Brad Joe • Approve business lease for us as the people who come to the museum say Storyteller Tim Tingle G09-1778 with Vangard Wire- it is for them,” said Chief Gregory E. -

Raid on the Bataan Death Camp

Raid on the bataan death camp click here to download The raid on Cabanatuan remains the most successful rescue mission in My father escaped the Death March. It's been 70 years since a daring raid freed captured Americans. It leads across the plain toward the death camp where prisoners of the horrors of the Bataan Death March -- when the men who had surrendered at. And while Hitler's concentration camps deserve their worldwide in it the Bataan Death March after thousands of USAFFE soldiers died from. December 8th, With the American fleet still smoldering in Pearl Harbor, the Japanese unleash their war machine on the Philippines. Thousands of. POW Camp Fukuoka Includes veterans biographies, Bataan Death March, Rules laid down by the Japanese camp commandant were: . Stoop, Little Speedo, Air Raid, Laughing Boy, Donald Duck, Many Many, Beetle Brain, Fish Eyes. Great Raid on Cabanatuan Prison information and photos from defense of Bataan and Corregidor and the infamous Bataan Death. The Great Raid--The Facts Behind the Story survivors of the infamous Bataan Death March who had been imprisoned for Of particular concern was the fate of some allied POWs being held in the Cabanatuan Camp in central Luzon. Documentary · Add a Plot» History | Episode aired 1 December Season 2 | Episode 5. Previous · All Episodes (23) · Next · WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Camp Poster. All the Bataan prisoners initially ended up at Camp O'Donnell. (It was and 10, Filipinos died at Camp O'Donnell within the first six weeks. Before the Cabanatuan raid was carried out, prisoners in a camp near and torture after the battle for Corregidor and the Bataan Death March. -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education. -

VA Office of Tribal Government Relations Newsletter ~ January/February 2019

VA Office of Tribal Government Relations Newsletter ~ January/February 2019 Hello and welcome to the latest VA Office of Tribal Government Relations (OTGR) newsletter. Can you believe it’s March? I know it’s already been quite a winter for most of the country. We’ve seen record snowfall and many areas are bracing for more frigid temperatures and precipitation in the coming days. I am encouraged by the calendar which tells us that spring is a mere three weeks away and we’ll finally get to thaw out and see new growth all around us. The Department of Veterans Affairs was, fortunately, not closed during the government shut down, so Veterans continued to be served and our team was able to proceed with scheduled meetings, outreach and training engagements with tribal partners and programs. It was challenging without our federal family partners (IHS, HUD, BIA) but everyone is back to work and we are collectively moving forward. In recent weeks, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct interviews with Tribal Veteran Service Officers (TVSOs) and tribal Veterans program staff from nine different tribes. You’ll find two of the interviews below, one with Geri Opsal, TVSO for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate in South Dakota and another with R.E. Lucero, who assists Veterans and their families of the Ute Indian Tribe in Utah. The TVSOs and Veterans program staff shared helpful information about the structure and organization of their respective tribal Veterans programs, illustrating how some TVSOs attained accreditation status as service officers whereas other tribes prefer to rely on local partners to assist with Veterans claims. -

View Pathfinder Travel Guide

PATHFINDER FALL / WINTER 2021 ChoctawCountry.com Indulge your curiosity. HALITO! [Hello] It is with great pride that I welcome you to Choctaw Country! When the air starts to cool down and the leaves begin to change, I find myself getting excited. In Choctaw Country, there are so many wonderful things to look forward to during the fall and winter seasons! Take a brisk (or long) hike through the stunning fall foliage, find some of the greatest hunting and fishing spots for miles around, or treat yourself during perfect camping temperatures to a spectacular view of the stars. Whether you are looking for a peaceful retreat or a weekend adventure, our community members are here to welcome you with open arms and true Southern hospitality. At every turn, you will find history, nature, excitement and, most importantly, culture. So, come experience the Choctaw Nation and see for yourselves! Chi Pisa La Chike! [Be seeing you] Chief Gary Batton 3 Stray from the beaten path. CONTENTS EVENTS CAMPING & LODGING 6 24 SOCIAL MEDIA HIKING 9 26 COFFEE SHOP STOPS FISHING 10 28 SATISFY YOUR SWEET TOOTH HUNTING 12 30 BREWERIES/DISTILLERIES/ MOTORCYCLE TOURING WINERIES 32 14 STARGAZING CULTURAL CENTER 34 16 CASINOS MUSEUMS 36 18 TRAVEL PLAZAS FOLIAGE SIGHTSEEING 38 20 INFORMATION LISTING STATE PARKS/LAKE ACTIVITIES 40 22 Have big fun in a small town. Visit ChoctawCountry.com EVENTS SEPTEMBER 18 / BUTTERFIELD BIKER BASH OCTOBER 1-2 / ROCK THE EQUINOX The now famous Butterfield Trail was the main route for Calling all metal heads! Rock the Equinox returns to Lake pioneers traveling west to search for gold, adventure and a better John Wells in Stigler this year with a huge lineup of local and life. -

Choctaw Nation Honored at 2010 Drum Awards the Inaugural 2010 Drum Awards Were Held Nov

Aragon Thanksgiving Choctaw A wood named celebrations artist sculptor’s Secretary shares style of VA talents Page 5 Pages 10-12 Page 16 Page 17 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma December 2010 Issue Serving 204,350 Choctaws Worldwide Choctaws ... growing with pride, hope and success Choctaw Nation honored at 2010 Drum Awards The inaugural 2010 Drum Awards were held Nov. 1 at the Event Center in Durant. Among the honorees were the Choctaw Code Talkers and the Scholarship Ad- visement Program. At right, Chief Gregory E. Pyle and Judy Allen, ex- ecutive director of Public Relations, accept the Pa- triotism Award on behalf of the Choctaw Code Talkers of World War I. Far right, Jo McDaniel and the staff of SAP accept the Educators Drum Award. Monica Brittingham, front left, served as the awards presenter for the ceremony. Tribal Council Williston becomes District 1 Councilman holds November Newspaper marks many milestones regular session The Choctaw Nation November 1975 Makes its mark Tribal Council met Nov. Volume 1 of Hello Choctaw, the first official pub- 13 in regular session at lication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, was Tushka Homma. New published on Nov. 1, 1975. business included several budgets and budget revi- June 1978 Name change sions for the new fiscal The name was changed to BISHINIK to better year. All were approved. reflect the culture. It was meant to be named Bis- On the agenda were kinik after the little Chahta news bird.