Klipsun Magazine, 2002, Volume 33, Issue 01 - November

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks, Recreation, Open Space Plan

City of Bellingham 2008 Parks, Recreation and Open Space Plan Amended Comprehensive Plan Chapter 7 Acknowledgements City Staff Paul Leuthold, Parks and Recreation Director Leslie Bryson, Design and Development Manager Marvin Harris, Park Operations Manager Dick Henrie, Recreation Manager Greg Aucutt, Senior Planner Alyssa Pitingoro, Intern Steering Committee Harry Allison, Park Board Mike Anderson, Park Board Tom Barrett, Park Board Jane Blume, Park Board Julianna Guy, Park Board William Hadley, Park Board Ira Hyman, Park Board John Hymas, Park Board Adrienne Lederer, Park Board Jim McCabe, Park Board Mark Peterson, Park Board John Blethen, Greenway Advisory Committee Edie Norton, Greenway Advisory Committee Judy Hoover, Planning Commission Del Lowry, Whatcom County Parks Commission Gordon Rogers, Whatcom County Parks Commission Sue Taylor, Citizen Consultants Hough Beck & Baird Inc. Applied Research Northwest Henderson, Young & Company Cover Photo Credits: Cornwall Park Fall Color by Dawn-Marie Hanrahan, Whatcom Falls by Jeff Fischer, Civic Aerial by Mike DeRosa Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Community Setting 5 Chapter 3 Existing Facilities 17 Chapter 4 Land and Facility Demand 25 Chapter 5 Goals and Objectives 31 Chapter 6 Recommendations 39 Chapter 7 Implementation 51 Appendices A. Park Classifications B. Existing Facility Tables C. Proposed Facility Tables D. North Bellingham Trail Plan Detail E. 2008 Adopted Capital Facilities Plan (6 Year) F. Revenue Source Descriptions Supporting Available at Documentation -

2010 Silver Beach Neighborhood Plan

[1] 2010 Silver Beach Neighborhood Plan Silver Beach Neighborhood – August 30, 2011 [2] Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Framework and Goals ................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 1: Vision Statement ................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 2: Past and Present .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 3: Broad Goal Statements for the Future ................................................................................................ 9 Chapter 2: Silver Beach Land Use .............................................................................................................................. 11 Part 1: Area Descriptions ............................................................................................................................. 11 Part 2: Analysis and Objectives for Future Land Use .................................................................................. 15 Part 3: Implementation Strategy ................................................................................................................... 16 Chapter 3: Transportation ........................................................................................................................................... -

The Planet, 2017, Spring

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR The lP anet Western Student Publications Spring 2017 The lP anet, 2017, Spring Frederica Kolwey Western Washington University Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kolwey, Frederica and Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University, "The lP anet, 2017, Spring" (2017). The Planet. 77. https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet/77 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Planet by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■"*■1 P/;. ■■■ THEPLANET CLEAN WATER ISSUE SPRING 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Frederica Kolwey ADVISER Warren Cornwall MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Wise EDITORS Keiko Betcher Rachel Hunter Allura Petersen PHOTO EDITOR Mike Hitchner SCIENCE EDITOR Erik Faburrieta DESIGNERS Alicia Terry DEAR READER, Oliver Amyakar In March I attended a workshop on Orcas Island organized to help San Juan island communities prepare Andy Lai for a possible oil spill in the Salish Sea. Scientists spoke of the risk to marine life and the Coast Guard Frances Dierken outlined what they would do if a spill happened. The workshop helped people understand their collective risk and illuminated their collective resources. WRITERS Madison Churchill In the aftermath of a disaster, communities with strong social ties have been found to recover faster than Christina Darnell Xander Davidson communities with severe social divides. -

Whatcom, Squalicum, and Padden Creeks TMDL Water Quality Improvement Report

Whatcom, Squalicum, and Padden Creeks Temperature Total Maximum Daily Load Water Quality Improvement Report June 2011 Publication No. 11-10-019 Publication and Contact Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at http://www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/1110019.html For more information contact: Washington State Department of Ecology Bellingham Field Office Water Quality Program 1440 - 10th Street, Suite 102 Bellingham, WA 98225 Phone: 360 715-5200 Washington State Department of Ecology - www.ecy.wa.gov/ o Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Yakima 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Cover photo: Pixi Falls in Whatcom Falls Park. Project Codes and 1996 303(d) Water-body ID Numbers Data for this project are available at Ecology’s Environmental Information Management (EIM) website at www.ecy.wa.gov/eim/index.htm. Search User Study ID, NCRI0002. Activity Tracker Codes (Environmental Assessment Program) are 04-040 and 09-183. TMDL Study Code (Water Quality Program) is WhaC01TM. The Squalicum/Padden Innovative project does not have a separate code. Water-body Numbers: WA-01-1622, WA-01-3110, WA-01-3200, WA-01-3210, WA-01-3215, WA-01-3220, WA-01-3225 Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the author or the Department of Ecology. If you need this document in a format for the visually impaired, call the Water Quality Program at 360-407-6600. -

Welcome Marathon Athletes! Wl We Are So Pleased to Have the Opportunity to Take Care of You, While Here for Your Marathon!

Lakeway Inn & Conference Center Bellingham, WA 714 Lakeway Drive Marathon Lodging Room Block Information www.thelakewayinn.com Welcome Marathon Athletes! wl We are so pleased to have the opportunity to take care of you, while here for your marathon! Reservations: Please call 1-888-671-1011 and ask for “Bellingham Bay Marathon” to reserve your room. Deadline: Call before Friday, August 25, 2015 to receive the discount. Lodging Block Dates: September 24 - 28, 2015 | Rate: $139.00 King or Double/Queen Room: (Typically $169 - $199/night) Let us treat you to a true full-service experience: Newly Renovated Northwest Inspired Guest Rooms & Suites! The Lakeway Inn offers brand new, renovated132 spacious guest rooms and suites, which include Northwest inspired furniture & décor, deluxe bedding packages, 42 inch flat panel televisions, microwaves, refrigerators, complimentary WI-FI, high- speed internet, upgraded bathroom amenities and more! Indoor Pool & Hot Tub: The Lakeway Inn offers for health, relaxation and well being a year-round indoor pool & hot tub atrium, women’s and men’s dry sauna and 24-hour fitness room. 24-hour Business Center: Two computer stations with high speed Internet and Microsoft Office programs, color printers, self-serve black & white copier, self-serve fax machine and ATM machine. Complimentary Shuttle Transportation to and from the Bellingham International Airport, Greyhound & Amtrak Station & Bellingham Cruise Terminal and within a 5 mile radius of the hotel. Complimentary parking. Generally speaking, our shuttle seats 6 with luggage and 7 without. Newly Renovated Lobby and Chinuk Restaurant: Open Monday through Sunday from 6 a.m. to close. The menu features the freshest local ingredients for breakfast, lunch and dinner. -

Silver Beach Letter of Intent

Wendy Harris, RECEIVED On behalf of Petitioners NOV 3 0 2007 3925 E. Connecticut Street Bellingham, WA 98226 City of Bellingham (360) 922-0442 Planning [email protected] Tim Stewart, Planning Director City of Bellingham Planning and Community Development Department 210 Lottie Street Bellingham, Wa, 98225 November 30, 2007 LETTER OF INTENT To Submit Neighborhood Plan Amendment Application For The "Complete" Silver Beach Neighborhood Plan Pursuant to the provisions of BMC Sec. 20.20.020 B, and BMC Sec. 21.10.150 B(l )(b ), the below signed Silver Beach residents ("petitioners") request that the Bellingham Planning Director initiate the "complete" Silver Beach Neighborhood plan amendment, which is attached hereto as Attachment A. Petitioners request that the complete plan amendment be docketed concurrently with, and joined to, the "official" neighborhood plan amendment that was submitted by the Silver Beach Neighborhood Association ("SBNA"). Further, petitioners request that, pursuant to BMC Sec. 21. l 0.190 A, the Director waive normal submittal requirements for review of this application as such necessary information is contained in the application filed by the SBNA, rendering additional documentation duplicative. Finally, petitioners request that any relevant fees for this application be waived on the theory that the "complete" plan amendment is, in fact, the true result of the neighborhood plan review process required under BMC Sec. 20.20.070. This assertion is supported by the facts discussed below, and in the separate request -

GET LUCKY a St

FUZZ BUZZ P.09 + INSIDE AN EPIDEMIC P.10 + BEST OF SKAGIT BALLOT P.15 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM*SKAGIT*SURROUNDING AREAS 03-11-2020 • ISSUE: 11 • V.15 GET LUCKY A St. Patty's Day roundup P.16 IRISH SPRING A jaunt to County Clare P.12 EPIC PRESENT TENSE Women Painters of ENGAGEMENT Washington Saga of the Völsungs P.13 P.14 WORDS John Hoyte: 10am, Sumas Library A brief overview of this Susan Welch: 3pm, Lummi Island Library 23 Bob Storms: 4pm, Ferndale Library week’s happenings Julie Tate-Libby: 4pm, Village Books FOOD THISWEEK COMMUNITY Wellness Fair: 11am-3pm, Skagit Valley Food 20 Co-op St. Patrick’s Day Parade: 12pm, downtown Bellingham B-BOARD Let’s Talk About Race: 7:30pm, Lummi Island Library 19 GET OUT Dallas Kloke Sunset Loop Relay: 9am, Washing- FILM ton Park, Anacortes Runnin’ O’ the Green: 10am, Boundary Bay Beer Garden 16 Anacortes Dash and Splash: 10am, Seafarers Memorial Park MUSIC Gear Sale: 10am-2pm, Burlington Parks and Rec Don your green Center 14 FOOD ART apparel for the Winter Farmers Market: 9am-2pm, Depot Arts annual Bellingham Center, Anacortes Pi Day Pie Contest: 1pm-2:30pm, Lynden Library 13 St. Patrick’s Day Wine Tasting: 2pm-4pm, Seifert & Jones Wine Merchants STAGE Parade taking place Ceilidh-bration: 5:30pm, Littlefield Celtic Center, Sat., March 14 in the Mount Vernon 12 VISUAL downtown core. Family Activity Day: 10am-3pm, Whatcom Mu- GET OUT seum’s Lightcatcher Building Present Tense Opening: 4:30pm-8:30pm, Matzke WEDNESDAY [03.11.20] Fine Art Gallery, Camano Island 10 Artists on the Edge: 5:3pm, Anacortes Port GET OUT Transit Shed Daffodil Festival: through March 31, Skagit Valley WORDS Pianist Jessica SUNDAY [03.15.20] [03. -

Window on Western, 2000, Volume 06, Issue 03 Kathy Sheehan

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Window on Western Western Publications Spring 2000 Window on Western, 2000, Volume 06, Issue 03 Kathy Sheehan Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices,es W tern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kathy and Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices, Western Washington University, "Window on Western, 2000, Volume 06, Issue 03" (2000). Window on Western. 15. https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western/15 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Window on Western by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spring 2000 News for Alumni and Friends of Western Washington University VOL 6, NO. 3 Exemplary Alumni of the Century Much laughter, a few tears and great inspiration marked the Feb. 25 Centennial dinner saluting 21 Exemplary F Alumni who represent the accomplishments of more than 100,000 graduates. Alumni board president-elect Larry Taylor was the "mas ter of celebrations" as award recipients stirringly recalled eight decades of campus life and honored the faculty, staff and fellow students who had shaped their lives. Among the honorees were Kathleen Taft ('25), left, who has had a law practice in Spokane since 1949; and CarroU Haeske ('22) and Jessica Lee ('92), at right. Haeske is the oldest honoree. Lee is the youngest. See all 21 Exemplary Alumni on pages 6 and 7. jason Koski photos Wider use of technology enhances the Western By Annette Bagley "All of that is s Western's Centennial Western at The other half register cation and Western was obligated changing. -

An Analysis of Self-Guided Historic Walking Tours in Whatcom County, Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2016 History at Hand: An Analysis of Self-Guided Historic Walking Tours in Whatcom County, Washington Laura M. (Laura Marie) Stone Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Stone, Laura M. (Laura Marie), "History at Hand: An Analysis of Self-Guided Historic Walking Tours in Whatcom County, Washington" (2016). WWU Graduate School Collection. 539. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/539 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History at Hand: An Analysis of Self-Guided Historic Walking Tours in Whatcom County, Washington By Laura Stone Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Sarah Campbell Dr. Daniel Boxberger Dr. Joyce Hammond MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

The Planet, 1991, Volume 20, Issue 03

Western Washington University Western CEDAR The Planet Western Student Publications Spring 1991 The Planet, 1991, Volume 20, Issue 03 Michael J. Lehnert Western Washington University Associated Students Environmental Center, Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lehnert, Michael J. and Associated Students Environmental Center, Western Washington University, "The Planet, 1991, Volume 20, Issue 03" (1991). The Planet. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet/5 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Planet by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. liilllMMK ^iRCMrvEs: Bagels and juice By Sara Olason I’m sure Bill Lane has tasted fancier fare. Spread on the table before him was a student-style lunch of apple Juice, bagels, cookies and smoked tofu. As former U.S. Ambassador to Aus tralia and recently retired pub lisher of Sunset magazine. Bill had us aspiring young journalists somewhat awestruck -- especially when he displayed the palm-sized telephone he kept tucked in a breast pocket for calls around the globe. But that simple lunch we shared with Bill in March was a bonus, giving a dozen students a chance to learn from his experi ence in publishing, public service and conservation. L. W. “Bill” Lane Jr. has been a door-to-door Sunset salesman, mountain guide and packer, naval L to R., Gary Gray, LW. -

The Planet, 2002, Winter

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR The lP anet Western Student Publications Winter 2002 The lP anet, 2002, Winter Levi Pulkkinen Western Washington University Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pulkkinen, Levi and Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University, "The lP anet, 2002, Winter" (2002). The Planet. 36. https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet/36 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Planet by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dear Reader, For most of history, rivers both created and destroyed communities. Some of the Editor-in-Chief: oldest civilizations exist today because people formed communities to maintain Levi PulI^J^inen dikes and prevent flooding. If the dikes failed, so did the community; floods Associate Editors: Kate Koch smashed homes and harvests, leaving the people to shiver and starve. Sarah Loehndorf People found life easier near the river where they could farm and fish freely. Science Editor: Long before Europeans began moving into the Pacific Northwest, American Colin Dietrich Indians had already developed a rich culture along the area’s riverbanks and shore Designers: lines. The salmon in the Nooksack River and the shellfish in Bellingham Bay sus Mary Berkley tained them, as they would white settlers during 19th and 20th centuries. -

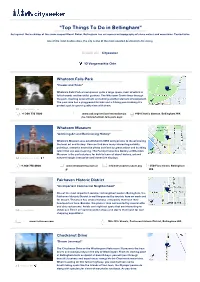

Top Things to Do in Bellingham" Set Against the Backdrop of the Snow-Capped Mount Baker, Bellingham Has an Impressive Topography of Azure Waters and Mountains

"Top Things To Do in Bellingham" Set against the backdrop of the snow-capped Mount Baker, Bellingham has an impressive topography of azure waters and mountains. Touted to be one of the most livable cities, the city is one of the most coveted destinations for skiing. Erstellt von : Cityseeker 10 Vorgemerkte Orte Whatcom Falls Park "Creeks and Trails" Whatcom Falls Park encompasses quite a large space, most of which is full of woods and beautiful gardens. The Whatcom Creek flows through the park, meeting several trails and adding another element of enjoyment. The park also has a playground for kids and a fishing pond making it a perfect spot to spend quality time with them. by Ken Haufle +1 360 778 7000 www.cob.org/services/recreation/pa 1401 Electric Avenue, Bellingham WA rks-trails/whatcom-falls-park.aspx Whatcom Museum "Admiring Art and Reminiscing History" Whatcom Museum was established in 1892 and pertains to disseminating the local art and history. You can find here many interesting exhibits, paintings, artworks extensive photo archives by great artists and budding talent that are awe-inspiring. The Family Interactive Gallery at Whatcom Museum is the perfect place for kids to learn all about history, art and by Benjamin Cody nature through interactive and immersive displays. +1 360 778 8930 www.whatcommuseum.or [email protected] 250 Flora Street, Bellingham g/ WA Fairhaven Historic District "An Important Commercial Neighborhood" One of the most important commercial neighborhoods in Bellingham, the Fairhaven Historic District is well frequented by tourists here on work and for leisure. The place has several famous companies that have their headquarters here.