The Planet, 2002, Winter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks, Recreation, Open Space Plan

City of Bellingham 2008 Parks, Recreation and Open Space Plan Amended Comprehensive Plan Chapter 7 Acknowledgements City Staff Paul Leuthold, Parks and Recreation Director Leslie Bryson, Design and Development Manager Marvin Harris, Park Operations Manager Dick Henrie, Recreation Manager Greg Aucutt, Senior Planner Alyssa Pitingoro, Intern Steering Committee Harry Allison, Park Board Mike Anderson, Park Board Tom Barrett, Park Board Jane Blume, Park Board Julianna Guy, Park Board William Hadley, Park Board Ira Hyman, Park Board John Hymas, Park Board Adrienne Lederer, Park Board Jim McCabe, Park Board Mark Peterson, Park Board John Blethen, Greenway Advisory Committee Edie Norton, Greenway Advisory Committee Judy Hoover, Planning Commission Del Lowry, Whatcom County Parks Commission Gordon Rogers, Whatcom County Parks Commission Sue Taylor, Citizen Consultants Hough Beck & Baird Inc. Applied Research Northwest Henderson, Young & Company Cover Photo Credits: Cornwall Park Fall Color by Dawn-Marie Hanrahan, Whatcom Falls by Jeff Fischer, Civic Aerial by Mike DeRosa Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Community Setting 5 Chapter 3 Existing Facilities 17 Chapter 4 Land and Facility Demand 25 Chapter 5 Goals and Objectives 31 Chapter 6 Recommendations 39 Chapter 7 Implementation 51 Appendices A. Park Classifications B. Existing Facility Tables C. Proposed Facility Tables D. North Bellingham Trail Plan Detail E. 2008 Adopted Capital Facilities Plan (6 Year) F. Revenue Source Descriptions Supporting Available at Documentation -

SAMISH WAY URBAN VILLAGE SUBAREA PLAN City of Bellingham, Washington

SAMISH WAY URBAN VILLAGE SUBAREA PLAN City of Bellingham, Washington Planning & Community Development Department Adopted by Ordinance No. 2019-12-038 December 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................. 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE SUBAREA PLAN.................................................. 1 1.2 RELATIONSHIP TO THE 2016 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN..................... 1 1.3 THE PLANNING PROCESS............................................................... 2 1.4 NATURAL AND HISTORIC CONTEXT................................................ 4 History of Samish Way................................................................ 4 The Area Today .......................................................................... 4 2. VISION.......................................................................................... 7 2.1 REDEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL....................................................... 9 3. DEVELOPMENT CHARACTER.......................................................... 11 3.1 DEVELOPMENT CHARACTER POLICIES............................................ 12 Land Use Policies........................................................................ 12 Site Design Policies..................................................................... 13 Building Design Policies.............................................................. 13 3.2 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES...................................................... 15 4. CIRCULATION, STREETSCAPE AND PARKING.................................. -

Position Description GENERAL MANAGER - KUGS-FM/KVIK-TV

DRAFT Position Description GENERAL MANAGER - KUGS-FM/KVIK-TV The Dean of Student’s administrative unit is comprised of Student Activities, the Viking Union Facilities, and the Office of Student Life. The unit provides services and support in a diverse range of functions to support individual student development and student organizational leadership opportunities. The Student Activities department provides management and advisement services for the Associated Students’ governance, programming, personnel and organizational activities; and the administration of policies governing student and campus activities. The Viking Union provides facilities and services for the students, the campus and community, including meeting and event facilities, coordination of retail food services, and a wide variety of programs and services. The two departments coordinate resources and activities to maximize service to the campus community. The General Manager-KUGS-FM/KVIK-TV provides management, instruction and professional expertise to the student initiated programs of KUGS-FM/KVIK-TV to develop and maintain a comprehensive and diverse schedule of services and programming for the benefit of WWU students and the campus community. The General Manger is responsible for the operation of KUGS-FM/KVIK-TV in accordance with relevant laws and regulations. The General Manager provides students with opportunities for leadership development through participation in extracurricular and co-curricular experiences that enhance their college experience. The General Manager initiates internships for students; networks with others in the broadcasting field as a liaison and researches educational opportunities for students and community members in media/broadcasting. The General Manager is the advisor to the Associated Students Election Coordinator in the management of the election process. -

Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01 Kathy Sheehan Western Washington University

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Window on Western Western Publications Fall 1998 Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01 Kathy Sheehan Western Washington University Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices,es W tern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kathy and Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices, Western Washington University, "Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01" (1998). Window on Western. 10. https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western/10 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Window on Western by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fall 1998 WINDOWNews for Alumni and Friends of Western WashingtonON University WESTERNVOL 5, NO. 1 ' r.% am 9HI <•* iii m t 4 ; Professor Richard Emmerson, Olscamp award winner Kathy Sheehan photo A youthful curiosity leads to excellence rofessor Richard Emmerson's parents Emmerson, who came to Western in 1990 provided him with a good grounding as chair of the English department, has been in religious matters, helping him to conducting research on the Middle Ages for understand the Bible and biblical his nearly 30 years, including a year he spent tory, up to the early Christian church. Later, abroad during his undergraduate days. his high school history teachers taught him During his sophomore year in England, he American history, beginning, of course, with enrolled in his first English literature course 1492. -

2010 Silver Beach Neighborhood Plan

[1] 2010 Silver Beach Neighborhood Plan Silver Beach Neighborhood – August 30, 2011 [2] Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Framework and Goals ................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 1: Vision Statement ................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 2: Past and Present .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part 3: Broad Goal Statements for the Future ................................................................................................ 9 Chapter 2: Silver Beach Land Use .............................................................................................................................. 11 Part 1: Area Descriptions ............................................................................................................................. 11 Part 2: Analysis and Objectives for Future Land Use .................................................................................. 15 Part 3: Implementation Strategy ................................................................................................................... 16 Chapter 3: Transportation ........................................................................................................................................... -

Cascadia BELLINGHAM's NOT-SO

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 08/29/07 :: 02.35 :: FREE TORTURED TENURE, P. 6 KASEY ANDERSON, P. 20 GLOBAL WARNING, P. 24 BELLINGHAM’S NOT-SO- PROUD PAST, P.8 HOUND JAZZ FESTIVAL: BELLINGHAM HOEDOWN: DOG AURAL ACUMEN IN TRAVERSE: DAYS OF SUMMER, P. 16 ANACORTES, P. 21 SIMULATING THE SALMON, P. 17 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS Sustainable ] 35 UNIQUE PLANTS Communities ][ FOOD FOR NORTHWEST & land use conference 28-33 GARDENS Thursday, September 6 ornamentals, natives, fruit ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ LANDSCAPE & 24-27 DESIGN SERVICES ][ FILM Fall Hours start Sept. 5: Wed-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20-23 Summer: Wed-Sat 10-5 , Goodwin Road, Everson Join Sustainable Connections to learn from key ][ MUSIC ][ www.cloudmountainfarm.com stakeholders from remarkable Cascadia Region 19 development featuring: ][ ART ][ Brownfields Urban waterfronts 18 Modern Furniture Fans in Washington &Canada Urban villages Urban growth areas (we deliver direct to you!) LIVE MUSIC Rural development Farmland preservation ][ ON STAGE ][ Thurs. & Sat. at 8 p.m. In addition, special hands on work sessions will present 17 the opportunity to get updates on, and provide feedback to, local plans and projects. ][ GET ][ OUT details & agenda: www.SustainableConnections.org 16 Queen bed Visit us for ROCK $699 BOTTOM Prices on Home Furnishings ][ WORDS & COMMUNITY WORDS & ][ 8-15 ][ CURRENTS We will From 6-7 CRUSH $699 Anyone’s Prices ][ VIEWS ][ on 4-5 ][ MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO $569 .07 29 A little out of the way… 08. But worth it. 1322 Cornwall Ave. Downtown Bellingham Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia CASCADIA WEEKLY #2.35 (Between Holly & Magnolia) 733-7900 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 www.LeftCoastFurnishings.com Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 2 *we reserve the right not to sell below our cost c . -

Stewards of the Lake Whatcom Reservoir

A CITY of BELLINGHAM GUIDE to the LAKE WHATCOM WATERSHED STEWARD S O F T H E SPRING 2007 Lake Whatcom is the source of drinking water to some 95,000 people in Whatcom County, including the 82,000 served by the City of Bellingham. The health of this tremendously important resource is declining, and at a pace that is faster than expected. Local governments are working hard to study the lake and make wise decisions about its future. We have made Lake Whatcom protection efforts a top priority for 2007, and will consider rigorous steps to This report is dedicated protect our lake. These steps will include protecting to the memory of more undeveloped land in the watershed, improving Bellingham City Council stormwater treatment, and helping watershed member Joan Beardsley, residents become better stewards of the lake. who helped initiate its creation before her death on March 12, 2007. Joan Protecting Lake Whatcom is our responsibility, was a long-time Bellingham not one we should leave to our children or resident, a much-loved grandchildren. There is no magic wand, there’s just and respected educator, us. We know the lake is changing, and for each day, and a thoughtful, engaged each month, each year we delay, it will take another community leader. May her day or month or year to bring our lake back to passion for the environment health. Let’s get the job done. and public service continue to inspire us all. Tim Douglas Mayor of Bellingham Nootka rose (Rosa nutkana) is native to Washington. WORKING TOGETHER T O P R E S E R V E A N D S TEWARD S O F T HE Why is the City publishing this report? WHAT’S INSIDE 4 How has Lake Whatcom changed? ake Whatcom, precious on its northwestern shoreline. -

The Planet, 2017, Spring

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR The lP anet Western Student Publications Spring 2017 The lP anet, 2017, Spring Frederica Kolwey Western Washington University Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kolwey, Frederica and Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University, "The lP anet, 2017, Spring" (2017). The Planet. 77. https://cedar.wwu.edu/planet/77 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Planet by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■"*■1 P/;. ■■■ THEPLANET CLEAN WATER ISSUE SPRING 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Frederica Kolwey ADVISER Warren Cornwall MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Wise EDITORS Keiko Betcher Rachel Hunter Allura Petersen PHOTO EDITOR Mike Hitchner SCIENCE EDITOR Erik Faburrieta DESIGNERS Alicia Terry DEAR READER, Oliver Amyakar In March I attended a workshop on Orcas Island organized to help San Juan island communities prepare Andy Lai for a possible oil spill in the Salish Sea. Scientists spoke of the risk to marine life and the Coast Guard Frances Dierken outlined what they would do if a spill happened. The workshop helped people understand their collective risk and illuminated their collective resources. WRITERS Madison Churchill In the aftermath of a disaster, communities with strong social ties have been found to recover faster than Christina Darnell Xander Davidson communities with severe social divides. -

Sehome Hill Communications Tower Replacement City Project No.: Eu-0179

City of Bellingham Request for Qualifications RFQ 20B-2016 SEHOME HILL COMMUNICATIONS TOWER REPLACEMENT CITY PROJECT NO.: EU-0179 Proposals Due: 11:00 AM April 22, 2016 City of Bellingham Purchasing Division 2221 Pacific Street Bellingham, Washington 98229 The City of Bellingham in accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. 2000d to 2000d-4 and Title 49, Code of Federal Regulations, Department of Transportation, subtitle A, Office of the Secretary, Part 21, nondiscrimination in federally assisted programs of the Department of Transportation issued pursuant to such Act, hereby notifies all bidders that it will affirmatively ensure that in any contract entered into pursuant to this advertisement, disadvantaged business enterprises as defined at 49 CFR Part 26 will be afforded full opportunity to submit bids in response to this invitation and will not be discriminated against on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex in consideration for an award. Request for Qualifications Sehome Hill Communications Tower Replacement #20B-2016 City Project # EU-0179 Published April 7,2016 Page 1 of 10 Section 1 – General Information 1.1 Purpose and Background The City of Bellingham (“City”) is soliciting for statements of qualifications (Invitation No. 20B- 2016) from interested consulting firms to provide professional design services to the Engineering Division of the Public Works Department for the Sehome Hill Communications Tower Replacement project (EU-0179). The City invites all interested parties to respond to this Request for Qualifications (RFQ) by submitting their qualifications relating to this type of project. Disadvantaged, minority and women-owned consultant firms are encouraged to respond. -

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual Communicating during Environmental Emergencies Northwest Area: Washington, Oregon, and Idaho able of Contents T Section Page 9202 Joint Information Center Manual ........................................ 9202-1 9202.1 Introduction........................................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2 Incident Management System.......................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.1 Functional Units .................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.2 Command ............................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2.3 Operations ........................................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.4 Planning .............................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.5 Finance/Administration....................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.6 Mandates ............................................................................. 9202-2 9202.2.7 Unified Command............................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.8 Joint Information System .................................................... 9202-3 9202.2.9 Public Records .................................................................... 9202-3 9202.3 Initial Information Officer – Pre-JIC................................................. 9202-3 9202.4 Activities of Initial Information Officer............................................ 9202-4 -

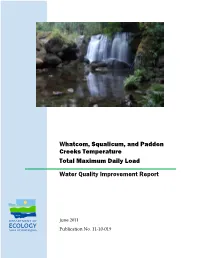

Whatcom, Squalicum, and Padden Creeks TMDL Water Quality Improvement Report

Whatcom, Squalicum, and Padden Creeks Temperature Total Maximum Daily Load Water Quality Improvement Report June 2011 Publication No. 11-10-019 Publication and Contact Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at http://www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/1110019.html For more information contact: Washington State Department of Ecology Bellingham Field Office Water Quality Program 1440 - 10th Street, Suite 102 Bellingham, WA 98225 Phone: 360 715-5200 Washington State Department of Ecology - www.ecy.wa.gov/ o Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Yakima 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Cover photo: Pixi Falls in Whatcom Falls Park. Project Codes and 1996 303(d) Water-body ID Numbers Data for this project are available at Ecology’s Environmental Information Management (EIM) website at www.ecy.wa.gov/eim/index.htm. Search User Study ID, NCRI0002. Activity Tracker Codes (Environmental Assessment Program) are 04-040 and 09-183. TMDL Study Code (Water Quality Program) is WhaC01TM. The Squalicum/Padden Innovative project does not have a separate code. Water-body Numbers: WA-01-1622, WA-01-3110, WA-01-3200, WA-01-3210, WA-01-3215, WA-01-3220, WA-01-3225 Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the author or the Department of Ecology. If you need this document in a format for the visually impaired, call the Water Quality Program at 360-407-6600. -

Welcome Marathon Athletes! Wl We Are So Pleased to Have the Opportunity to Take Care of You, While Here for Your Marathon!

Lakeway Inn & Conference Center Bellingham, WA 714 Lakeway Drive Marathon Lodging Room Block Information www.thelakewayinn.com Welcome Marathon Athletes! wl We are so pleased to have the opportunity to take care of you, while here for your marathon! Reservations: Please call 1-888-671-1011 and ask for “Bellingham Bay Marathon” to reserve your room. Deadline: Call before Friday, August 25, 2015 to receive the discount. Lodging Block Dates: September 24 - 28, 2015 | Rate: $139.00 King or Double/Queen Room: (Typically $169 - $199/night) Let us treat you to a true full-service experience: Newly Renovated Northwest Inspired Guest Rooms & Suites! The Lakeway Inn offers brand new, renovated132 spacious guest rooms and suites, which include Northwest inspired furniture & décor, deluxe bedding packages, 42 inch flat panel televisions, microwaves, refrigerators, complimentary WI-FI, high- speed internet, upgraded bathroom amenities and more! Indoor Pool & Hot Tub: The Lakeway Inn offers for health, relaxation and well being a year-round indoor pool & hot tub atrium, women’s and men’s dry sauna and 24-hour fitness room. 24-hour Business Center: Two computer stations with high speed Internet and Microsoft Office programs, color printers, self-serve black & white copier, self-serve fax machine and ATM machine. Complimentary Shuttle Transportation to and from the Bellingham International Airport, Greyhound & Amtrak Station & Bellingham Cruise Terminal and within a 5 mile radius of the hotel. Complimentary parking. Generally speaking, our shuttle seats 6 with luggage and 7 without. Newly Renovated Lobby and Chinuk Restaurant: Open Monday through Sunday from 6 a.m. to close. The menu features the freshest local ingredients for breakfast, lunch and dinner.