The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

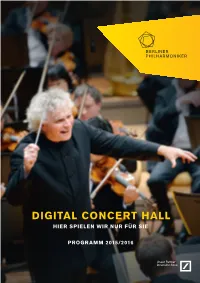

Dch Programm 15-16 De.Pdf

DIGITAL CONCERT HALL HIER SPIELEN WIR NUR FÜR SIE PROGRAMM 2015/2016 PROGRAMM 2015/2016 1 WILLKOMMEN IN DER DIGITAL CONCERT HALL Wer an klassische Musik denkt, denkt an Neben den symphonischen Konzerten Ludwig van Beethoven. Interpretationen sei- der Berliner Philharmoniker gibt es auch in ner Symphonien waren Höhepunkte der dieser Saison noch viel mehr in der Digital Amtszeiten sämtlicher Chefdirigenten der Concert Hall zu sehen und zu hören: Berliner Philharmoniker. In der Saison Late-Night-Konzerte, Education-Projekte, 2015/2016 legt Sir Simon Rattle seine Les- Kon zerte von Jugendorchestern und vielfäl- art dieser Werke vor – in der Berliner Philhar- tige Bonus-Filme. Kurz: Wie immer haben Sie monie ebenso wie in der Digital Concert Hall. Gelegenheit, in die ganze Welt der Berliner Philharmoniker einzutauchen. Darüber hinaus tritt Sir Simon zweimal als Operndirigent in Erscheinung. So steht Wagners Tristan und Isolde in einer konzer- www.digital-concert-hall.com tanten Aufführung mit Stuart Skelton und Eva-Maria Westbroek auf dem Programm. Ein weiteres berühmtes Liebespaar begegnet uns in Debussys Pelléas et Mélisande – hier in der Regie von Peter Sellars und mit Chris- tian Gerhaher und Magdalena Kožená in den Titelpartien. Debussys Oper ist eingebettet in einen weiteren Programmschwerpunkt mit französischer Musik u. a. von Hector Berlioz, Henri Dutilleux, César Franck, Francis Poulenc, Maurice Ravel und Camille Saint- Saëns. Als Interpreten in diesen und vielen weiteren Werken aus allen Bereichen des symphonischen Repertoires sind wie immer herausragende Dirigenten und Solisten zu erleben. 2 DIGITAL CONCERT HALL TICKETS Als Besucher der Digital Concert Hall haben ABONNEMENT Sie die Wahl zwischen einem Abonnement FÜR MONATLICH 14,90 € und Tickets mit unterschiedlicher Laufzeit. -

Berliner Philharmoniker

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director November 12–13, 2016 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert I Saturday, November 12, 8:00 pm 3 Concert II Sunday, November 13, 4:00 pm 15 Artists 31 Berliner Philharmoniker Concert I Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director Saturday Evening, November 12, 2016 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 14th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the Eugene and Emily Grant Family Foundation. This evening’s supporting sponsor is the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. This evening’s performance is funded in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s performance is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Bill Lutes for speaking at this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Journeys International, sponsor of this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Aaron Dworkin, Melody Racine, Emily Avers, Paul Feeny, Jeffrey Lyman, Danielle Belen, Kenneth Kiesler, Nancy Ambrose King, Richard Aaron, and the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance for their support and participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Deutsche Bank is proud to support the Berliner Philharmoniker. Please visit the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker at www.digitalconcerthall.com. -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Scharoun Ensemble Berlin

SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE BERLIN Founded in 1983 by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Scharoun Ensemble is one of Germany’s leading chamber-music organizations. With its wide repertoire, ranging from composers of the Baroque period by way of Classical and Romantic chamber music to contemporary works, the Scharoun Ensemble has been inspiring audiences in Europe and overseas for more than a quarter of a century. Innovative programming, a refined tonal culture and spirited interpretations are hallmarks of the ensemble, which performs in a variety of instrumental combinations. The permanent core of the Scharoun Ensemble is a classical octet (clarinet, bassoon, horn, two violins, viola, cello and double bass), apart from Wolfram Brandl and Claudio Bohorquez they are made up entirely of members of the Berlin Philharmonic. When called for, the ensemble brings in additional instrumentalists as well as noted conductors. The Scharoun Ensemble has prepared and presented various programmes under the direction of Claudio Abbado, Sir Simon Rattle, Daniel Barenboim and Pierre Boulez. It has also performed with singers including Thomas Quasthoff, Simon Keenlyside and Barbara Hannigan, and, for interdisciplinary projects, the ensemble has engaged such artists as Fanny Ardant, Loriot and Dominique Horwitz. Bridging the gap between tradition and the modern is the Scharoun Ensemble’s principal artistic focus. It has given world premieres of many 20th- and 21st-century compositions while dedicating itself with equal passion to the interpretation of works from past centuries. Among the cornerstones of its repertoire are Franz Schubert’s Octet d803, with which the ensemble made its public debut in 1983, and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Septet Op.20. -

The Digital Concert Hall

Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall he time has finally come! Four years have Emmanuelle Haïm, the singers Marlis Petersen passed since the Berliner Philharmoniker – the orchestra’s Artist in Residence – Diana T elected Kirill Petrenko as their future chief Damrau, Elīna Garanča, Anja Kampe and Julia conductor. Since then, the orchestra and con- Lezhneva, plus the instrumentalists Isabelle ductor have given many exciting concerts, fuel- Faust, Janine Jansen, Alice Sara Ott and Anna ling anticipation of a new beginning. “Strauss Vinnitskaya. Yet another focus should be like this you encounter once in a decade – if mentioned: the extraordinary opportunities to you’re lucky,” as the London Times wrote about hear members of the Berliner Philharmoniker their Don Juan together. as protagonists in solo concertos. With the 2019/2020 season, the partnership We invite you to accompany the Berliner officially starts. It is a spectacular opening with Philharmoniker as they enter the Petrenko era. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, whose over- Look forward to getting to know the orchestra whelmingly joyful finale is perfect for the festive again, with fresh inspiration and new per- occasion. Just one day later, the work can be spectives, and in concerts full of energy and heard once again at an open-air concert in vibrancy. front of the Brandenburg Gate, to welcome the people of Berlin. Further highlights with Kirill Petrenko follow: the New Year’s Eve concert, www.digital-concert-hall.com featuring works by Gershwin and Bernstein, a concert together with Daniel Barenboim as the soloist, Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, Beethoven’s Fidelio at the Baden-Baden Easter Festival and in Berlin, and – for the European concert – the first appearance by the Berliner Philharmoniker in Israel for 26 years. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Biography, February 2013 Yannick Nézet-Séguin triumphantly opened his inaugural season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra in the fall of 2012. From the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall to the Carnegie Hall stage, Nézet-Séguin’s highly collaborative style, deeply-rooted musical curiosity, and boundless enthusiasm, paired with a fresh approach to orchestral programming, have been heralded by critics and audiences alike. The New York Times has called Yannick “phenomenal,” adding that under his baton, “the ensemble, famous for its glowing strings and homogenous richness, has never sounded better.” In his first official season in Philadelphia, Yannick has taken the Orchestra to new musical heights in concerts at home, and has further distinguished himself in the community, with a powerful performance at the Orchestra’s annual Martin Luther King Tribute Concert, working with young musicians from the School District of Philadelphia’s All City Orchestra, establishing a relationship with the Curtis Institute, and ringing in 2013 with his Philadelphia audience with a festive New Year’s Eve concert. Following on the heels of a February 2013 announcement of a recording project with Deutsche Grammophon, Yannick and the Orchestra will record Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring together. Over the past decade, Nézet-Séguin has established himself as a musical leader of the highest caliber and one of the most exciting talents of his generation. Since 2008 he has been music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic, and since 2000 artistic director and principal conductor of Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F.