A Conductor for the Ages Jonathan E.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Symphony Orchestra with Sir Simon Rattle, Music Director

LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WITH SIR SIMON RATTLE, MUSIC DIRECTOR PROGRAM BARTÓK Concerto for Orchestra (1881 – 1945) Duke Bluebeard’s Castle VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5 (1887 – 1959) MAHLER Symphony No. 4 in G Major (1860 – 1911) PROGRAM NOTES Written by Dan Ruccia BÉLA BARTÓK CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA Times were rough for Béla Bartók in 1943. He and his wife, pianist Ditta Pázstory, had migrated to the United States in 1940 to escape the pro-Nazi regime in Hungary, but had found limited success as performers. To survive, Bartók did some ethnomusicological work at Columbia and occasionally lectured there and at and Harvard, but he was generally unsatisfied with his situation. To make matters worse, his health had recently deteriorated; in February 1943, he collapsed after a lecture at Harvard. When he was admitted to the hospital, he weighed only 87 pounds. It wasn’t clear how much longer he had to live. Initially, the nature of Bartók’s illness was unclear. Early diagnoses included tuberculosis and polycythemia. It was only in April 1944 that doctors pinned down his actual diagnosis—chronic myeloid leukemia—but by then, there was little that could be done. In May 1943, conductor Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony commissioned a new orchestral work from Bartók through the recently formed Koussevitzky Music Foundation. The ailing composer was initially hesitant; he did not want to take a commission that he might not be able to finish. But Koussevitzky insisted that the commission was a fait accompli and the money could only go to Bartók. With the commission in hand, it seems that Bartók became energized. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2018 This

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2018 This is the fifteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2017-November 2018). The 130 selections have come from 25 members of the team and 70 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources - I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, 8 have received two nominations: Mahler and Strauss with Sergiu Celibidache on the Munich Phil choral music by Pavel Chesnokov on Reference Recordings Shostakovich symphonies with Andris Nelsons on DG The Gluepot Connection from the Londinium Choir on Somm The John Adams Edition on the Berlin Phil’s own label Historic recordings of Carlo Zecchi on APR Pärt symphonies on ECM works for two pianos by Stravinsky on Hyperion Chandos was this year’s leading label with 11 nominations, significantly more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2400 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year the choice was a little easier than usual. Pavel CHESNOKOV Teach Me Thy Statutes - PaTRAM Institute Male Choir/Vladimir Gorbik rec. 2016 REFERENCE RECORDINGS FR-727 SACD The most significant anniversary of 2018 was that of the centenary of the death of Claude Debussy, and while there were fine recordings of his music, none stood as deserving of this accolade as much as the choral works of Pavel Chesnokov. -

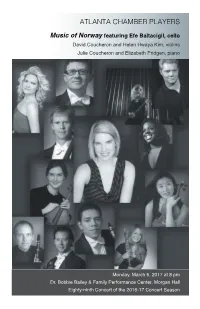

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

Bath Festival Orchestra Programme 2021

Bath Festival Orchestra photo credit: Nick Spratling Peter Manning Conductor Rowan Pierce Soprano Monday 17 May 7:30pm Bath Abbey Programme Carl Maria von Weber Overture: Der Freischütz Weber Der Freischütz (Op.77, The Marksman) is a German Overture to Der Freischütz opera in three acts which premiered in 1821 at the Schauspielhaus, Berlin. Many have suggested that it was the first important German Romantic opera, Strauss with the plot based around August Apel’s tale of the same name. Upon its premiere, the opera quickly 5 Orchestral Songs became an international success, with the work translated and rearranged by Hector Berlioz for a French audience. In creating Der Freischütz Weber Brentano Lieder Op.68 embodied the ideal of the Romantic artist, inspired Ich wollt ein Sträuẞlein binden by poetry, history, folklore and myths to create a national opera that would reflect the uniqueness of Säusle, liebe Myrthe German culture. Amor Weber is considered, alongside Beethoven, one of the true founders of the Romantic Movement in Morgen! Op.27 music. He lived a creative life and worked as both a pianist and music critic before making significant contributions to the operatic genre from his appointment at the Dresden Staatskapelle in 1817, Das Rosenband Op.36 where he realised that the opera-goers were hearing almost nothing other than Italian works. His three German operas acted as a remedy to this situation, Brahms with Weber hoping to embody the youthful Serenade No.1 in D, Op.11 Romantic movement of Germany on the operatic stage. These works not only established Weber as a long-lasting Romantic composer, but served to define German Romanticism and make its name as an important musical force in Europe throughout the 19th century. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Berliner Philharmoniker

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director November 12–13, 2016 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert I Saturday, November 12, 8:00 pm 3 Concert II Sunday, November 13, 4:00 pm 15 Artists 31 Berliner Philharmoniker Concert I Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director Saturday Evening, November 12, 2016 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 14th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the Eugene and Emily Grant Family Foundation. This evening’s supporting sponsor is the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. This evening’s performance is funded in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s performance is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Bill Lutes for speaking at this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Journeys International, sponsor of this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Aaron Dworkin, Melody Racine, Emily Avers, Paul Feeny, Jeffrey Lyman, Danielle Belen, Kenneth Kiesler, Nancy Ambrose King, Richard Aaron, and the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance for their support and participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Deutsche Bank is proud to support the Berliner Philharmoniker. Please visit the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker at www.digitalconcerthall.com. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

The Blake Collection in Memory of Nancy M

The Blake Collection In Memory of Nancy M. Blake BELLINI’S NORMA featuring CECILIA BARTOLI This tragic opera is set in Roman-occupied, first-century Gaul, features a title character, who although a Druid priestess, is in many ways a modern woman. Norma has secretly taken the Roman proconsul Pollione as her lover and had two children with him. Political and personal crises arise when the locals turn against the occupiers and Pollione turns to a new paramour. Norma “is a role with emotions ranging from haughty and demanding, to desperately passionate, to vengeful and defiant. And the singer must convey all of this while confronting some of the most vocally challenging music ever composed. And if that weren't intimidating enough for any singer, Norma and its composer have become almost synonymous with the specific and notoriously torturous style of opera known as bel canto — literally, ‘beautiful singing’” (“Love Among the Druids: Bellini's Norma,” NPR World of Opera, May 16, 2008). And Bartoli, one of the greatest living opera divas, is up to the challenges the role brings. (New York Public Radio’s WQXR’s “OperaVore” declared that “Bartoli is Fierce and Mercurial in Bellini's Norma,” Marion Lignana Rosenberg, June 09, 2013.) If you’re already a fan of this opera, you’ve no doubt heard a recording spotlighting the great soprano Maria Callas (and we have such a recording, too), but as the notes with the Bartoli recording point out, “The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta, who sang what today’s listeners would consider to be mezzo-soprano roles,” making Bartoli more appropriate than Callas as Norma. -

Simon O'neill ONZM

Simon O’Neill ONZM Tenor “Simon O'Neill made a tremendous debut in the title-role, giving notice that he is the best heroic tenor to emerge over the last decade.” Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph, UK. A native of New Zealand, Simon O’Neill is one of the finest helden-tenors on the international stage. He has frequently performed with the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Berlin, Hamburg and Bayerische Staatsopern, Teatro alla Scala and the Bayreuth, Salzburg, Edinburgh and BBC Proms Festivals, appearing with a number of illustrious conductors including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon Rattle, James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Valery Gergiev, Sir Antonio Pappano, Pietari Inkinen, Pierre Boulez, Sir Mark Elder, Sir Colin Davis, Simone Young, Edo de Waart, Fabio Luisi, Donald Runnicles, Sir Simon Rattle, Jaap Van Zweden and Christian Thielemann. Simon’s performances as Siegmund in Die Walküre at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden with Pappano, Teatro alla Scala and Berlin Staatsoper with Barenboim, at the Metropolitan Opera with Runnicles in the celebrated Otto Schenk production returning with Luisi in the Lepage Ring Cycle and in the Götz Friedrich production at Deutsche Oper Berlin with Rattle were performed to wide critical acclaim. He was described in the international press as "an exemplary Siegmund, terrific of voice", "THE Wagnerian tenor of his generation" and "a turbo-charged tenor". During this season’s engagements Simon makes his debut at: Tanglewood with the Boston Symphony and Andris Nelsons and the Toronto Symphony with Sir Andrew Davis and Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana with Henrik Nánási as Siegmund in concert performances of Die Walküre. -

Staatskapelle Dresden

Staatskapelle Dresden Staatskapelle Dresden Matthias Claudi PR und Marketing Theaterplatz 2 Christian Thielemann, Principal Conductor 01067 Dresden Germany Myung-Whun Chung, Principal Guest Conductor T 0351 4911 380 herberb Blomstedt, Conductor Laureate F 0351 4911 328 [email protected] Founded by Prince Elector Moritz von Sachsen in 1548, the Staatskapelle Dresden is one of the oldest orchestras in the world and steeped in tradition. Over its long history many distinguished conductors and internationally celebrated instrumentalists have left their mark on this onetime court orchestra. Previous directors include Heinrich Schütz, Johann Adolf Hasse, Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner, who called the ensemble his »miraculous harp«. The list of prominent conductors of the last 100 years includes Ernst von Schuch, Fritz Reiner, Fritz Busch, Karl Böhm, Joseph Keilberth, Rudolf Kempe, Otmar Suitner, Kurt Sanderling, Herbert Blomstedt and Giuseppe Sinopoli. The orchestra was directed by Bernard Haitink from 2002-2004 and most recently by Fabio Luisi from 2007-2010. Principal Conductor since the 2012 / 2013 season has been Christian Thielemann. In May 2016 the former Principal Conductor Herbert Blomstedt received the title Conductor Laureate. This title has only been awarded to Sir Colin Davis before, who held it from 1990 until his death in April 2013. Myung-Whun Chung has been Principal Guest Conductor since the 2012 / 2013 season. Richard Strauss and the Staatskapelle were closely linked for more than sixty years. Nine of the composer’s operas were premiered in Dresden, including »Salome«, »Elektra« and »Der Rosenkavalier«, while Strauss’s »Alpine Symphony« was dedicated to the orchestra. Countless other famous composers have written works either dedicated to the orchestra or first performed in Dresden. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca.