Kurigalzu's Statue Inscription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

Asher-Greve / Westenholz Goddesses in Context ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENTALIS

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources Asher-Greve, Julia M ; Westenholz, Joan Goodnick Abstract: Goddesses in Context examines from different perspectives some of the most challenging themes in Mesopotamian religion such as gender switch of deities and changes of the status, roles and functions of goddesses. The authors incorporate recent scholarship from various disciplines into their analysis of textual and visual sources, representations in diverse media, theological strategies, typologies, and the place of image in religion and cult over a span of three millennia. Different types of syncretism (fusion, fission, mutation) resulted in transformation and homogenization of goddesses’ roles and functions. The processes of syncretism (a useful heuristic tool for studying the evolution of religions and the attendant political and social changes) and gender switch were facilitated by the fluidity of personality due to multiple or similar divine roles and functions. Few goddesses kept their identity throughout the millennia. Individuality is rare in the iconography of goddesses while visual emphasis is on repetition of generic divine figures (hieros typos) in order to retain recognizability of divinity, where femininity is of secondary significance. The book demonstrates that goddesses were never marginalized or extrinsic and thattheir continuous presence in texts, cult images, rituals, and worship throughout Mesopotamian history is testimony to their powerful numinous impact. This richly illustrated book is the first in-depth analysis of goddesses and the changes they underwent from the earliest visual and textual evidence around 3000 BCE to the end of ancient Mesopotamian civilization in the Seleucid period. -

The Origin of the Mystical Number Seven in Mesopotamian Culture

The Origin of the Mystical Number Seven in Mesopotamian Culture: Division by Seven in the Sexagesimal Number System Kazuo MUROI §1. Introduction In Mesopotamian literary works, including hymns, myths, and incantations, the number 7 often occurs in mysterious circumstances where something of religious importance may be indicated. Although we do not yet completely understand the connotations of the mystical number 7 in these literary works, we know that the Sumerians of the third millennium BCE believed the number 7 – out of the many natural numbers – to be special. It seems that various Sumerian words containing the number 7 had taken firm root in their culture by the twenty-second century BCE at the latest. However, as yet we have had no convincing explanation for the Sumerians’ adherence to the number 7. Why did they select the number 7 as a mystical or sacred number? In this paper I shall attempt to clarify the origin of the mystical number 7 (1) by examining literary works containing the number 7, as well as some mathematical problems relating to division by 7. §2. The oldest examples of the mystical number 7 One of the oldest examples of the mystical number 7 is in the Early Dynastic Proverbs, Collection One written in the 26th century BCE (2) : lul-7 lu-lu “Seven lies are too numerous.” In addition to the lul-7 “seven lies” of this wordplay, we have several instances of a noun plus 7 in certain unusual orthographic texts, which are called UD-GAL-NUN texts, as well as normal orthographic texts:(3) UD-UD-7 “seven gods” urì-gal-7 “seven (divine) standards” ama-ugu 4-7 “mother who bore seven (children)” šeš-sila 4-7 “seven lamb brothers”. -

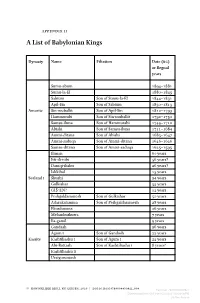

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

The Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon, About 2250 B.C

OukI 3 1924 074 445 523 All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE m---^ Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924074445523 THE CODE OF HAMMURABI KING OF BABYLON ABOUT 2250 B.C. , 1 C!.0 4\- 'd'Ol^ j-" irt'" AUTOGEAPHED TEXT TRANSLITERATION TRANS LATION GLOSSARY INDEX OF SUBJECTS LISTS OF PROPER NAMES SIGNS NUMERALS CORRECTIONS AND ERASURES WITH MAP FRONTISPIECE AND PHOTOGRAPH OF TEXT BY KOBERT FRANCIS HAKPEll Ph.D. rllOl'lSSflOR OF Till! BUMITIC LANGUAOUH AND LlTHUATUKHH IN TUB UNIVKB8ITV OK OIIICAQO DIBKOTOnOF TUB BAUVIjONIAN SECTION OF TUB OEIENTAL EXPLORATION FUND OF THE UNIVEKSITY OF OIIICAGO MANAGINQ EDITOR OF THE AMERICAN JOURNAL. OF 8EMITIC LANGUAGEH AND IjITERATURER FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOORAnilCAL SOCIETY ^ Chicuijo The University of Chicago Press Callaghan & Company London LuzAG & Company 1904 tt- -t-^t^r A Copyright, 1904 The University of Chicaoo TO MY FHJEND AND FORMER COLLEAGUE FRANKLIN P. MALL, M.D. DIRECTOR OF THE ANATOMICAL INSTITUTE OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY CONTENTS. Fkontispieoe —ffammurabi Receiving the Code from the Sim God Preface ix Introduction .... XI Transliteration and Translation 2 Index of Subjects 113 List of Proper Names 143 Glossary 147 Photooraph of Text Facing Plate I Autographed Text Plates I-LXXXII List of Signs Plates LXXXIII-XCVIII List of Numerals Plate XCIX List of Scribal Errors Plates C, CI List of Erasures Plate CII Map of Babylonia Plate cm PREFACE. -

The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Historia Religionum 35 The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess An Interpretation of Her Myths Therese Rodin Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Tun- bergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, 6 September 2014 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Britt- Mari Näsström (Gothenburg University, Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, History of Religions). Abstract Rodin, T. 2014. The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess. An Interpretation of Her Myths. Historia religionum 35. 350 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554- 8979-3. The present study is an interpretation of the two myths copied in the Old Babylonian period in which the Sumerian mother goddess is one of the main actors. The first myth is commonly called “Enki and NinপXUVDƣa”, and the second “Enki and Ninmaপ”. The theoretical point of departure is that myths have society as their referents, i.e. they are “talking about” society, and that this is done in an ideological way. This study aims at investigating on the one hand which contexts in the Mesopotamian society each section of the myths refers to, and on the other hand which ideological aspects that the myths express in terms of power relations. The myths are contextualized in relation to their historical and social setting. If the myth for example deals with working men, male work in the area during the relevant period is dis- cussed. The same method of contextualization is used regarding marriage, geographical points of reference and so on. -

Mesopotamian Legal Traditions and the Laws of Hammurabi

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 71 Issue 1 Symposium on Ancient Law, Economics and Society Part II: Ancient Rights and Wrongs / Article 3 Symposium on Ancient Law, Economics and Society Part II: Ancient Near Eastern Land Laws October 1995 Mesopotamian Legal Traditions and the Laws of Hammurabi Martha T. Roth Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Martha T. Roth, Mesopotamian Legal Traditions and the Laws of Hammurabi, 71 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 13 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol71/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MESOPOTAMIAN LEGAL TRADITIONS AND THE LAWS OF HAMMURABI MARTHA T. ROTH* I find myself, more and more frequently in recent years, asking the questions: "What are the Mesopotamian law collections?" and more broadly, "What is Mesopotamian law?" For twenty years I have wrestled with these issues, ever since my first graduate school class with Professor Barry Eichler at the University of Pennsylvania in 1974 opened my eyes to the intrigue and the soap opera of Nuzi family law. And in the last few years, as I have worked to complete new transla- tions of all the law collections, I have found my own opinions -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:11:41PM Via Free Access 208 Appendix III

Appendix III The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117 1 Shamshi-Adad I / Ishme-Dagan I vs. Hammurabi The synchronization of Hammurabi and the ruling family of Shamshi-Adad I’s kingdom can be proven by the correspondence between them, including the letters of Yasmah-Addu, the ruler of Mari and younger son of Shamshi-Adad I, to Hammurabi as well as an official named Hulalum in Babylon1 and those of Ishme-Dagan I to Hammurabi.2 Landsberger proposed that Shamshi-Adad I might still have been alive during the first ten years of Hammurabi’s reign and that the first year of Ishme- Dagan I would have been the 11th year of Hammurabi’s reign.3 However, it was also suggested that Shamshi-Adad I would have died in the 12th / 13th4 or 17th / 18th5 year of Hammurabi’s reign and Ishme-Dagan I in the 28th or 31st year.6 If so, the reign length of Ishme-Dagan I recorded in the AKL might be unreliable and he would have ruled as the successor of Shamshi-Adad I only for about 11 years.7 1 van Koppen, MARI 8 (1997), 418–421; Durand, DÉPM, No. 916. 2 Charpin, ARM 26/2 (1988), No. 384. 3 Landsberger, JCS 8/1 (1954), 39, n. 44. 4 Whiting, OBOSA 6, 210, n. 205. 5 Veenhof, AP, 35; van de Mieroop, KHB, 9; Eder, AoF 31 (2004), 213; Gasche et al., MHEM 4, 52; Gasche et al., Akkadica 108 (1998), 1–2; Charpin and Durand, MARI 4 (1985), 293–343. -

Babylonianstory of the Deluge Epic of Gilgamish

° BRITISH MUSEUM. The BabylonianStory of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamish With an Account of the Royal Libraries of Nineveh t WITH EIGHTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS • t 4 Q 1 i PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES. 1920. PRICE ONE SHILLINO_'_: _ '_-%._._%:_)_, g [/Ul Rights lteserv_.] .- ,,,, . : THE BABYLONIAN STORY OF THE DELUGE AS TOLD BY ASSYRIAN TABLETS FROM NINEVEH. THE DISCOVERY OF THE TABLETS AT NINEVEH BY LAYARD, RASSAM AND SMITH. IN I845-47 and again in I849-5I Mr. (later Sir) A. H. Layard carried out a series of excavations among the ruins of the ancient city of Nineveh, " that great city, wherein are more "' than sixteen thousand persons that Cannot discern between ""their right hand and their left; and also much cattle " (Jonah iv, II). Its ruins lie on the left or east bank of the Tigris, exactly opposite the town of A1-Maw.sil, or M6_ul, which was founded by the Sassanians and marks the site of Western Nineveh. At first Layard thought that these ruins were not those of Nineveh, which he placed at Nimrfid, about 2o miles downstream, but of one of the other cities that were builded by Asshur (see Gen. x, II, I2). Thanks, however, to Christian, Roman and Muh.ammadan tradition, there is no room for doubt about it, and tile site of Nineveh has always , been known. The fortress which the Arabs built there in the seventh century was known as ".Kal'at NtnawL" i.e., " Nineveh Castle," for many centuries, and all the Arab geographers agree in saying that the mounds opposite MSsul contain the ruins of the palaces and walls of Nineveh. -

OLD AKKADIAN WRITING and GRAMMAR Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu MATERIALS FOR THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY NO. 2 OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR BY I. J. GELB SECOND EDITION, REVISED and ENLARGED THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada c, 1952 and 1961 by The University of Chicago. Published 1952. Second Edition Published 1961. PHOTOLITHOPRINTED BY GUSHING - MALLOY, INC. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1961 oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS pages I. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF OLD AKKADIAN 1-19 A. Definition of Old Akkadian 1. B. Pre-Sargonic Sources 1 C. Sargonic Sources 6 D. Ur III Sources 16 II. OLD AKKADIAN WRITING 20-118 A. Logograms 20 B. Syllabo grams 23 1. Writing of Vowels, "Weak" Consonants, and the Like 24 2. Writing of Stops and Sibilants 28 3. General Remarks 4o C. Auxiliary Marks 43 D. Signs 45 E. Syllabary 46 III. GRAMMAR OF OLD AKKADIAN 119-192 A. Phonology 119 1. Consonants 119 2. Semi-vowels 122 3. Vowels and Diphthongs 123 B. Pronouns 127 1. Personal Pronouns 127 a. Independent 127 b. Suffixal 128 i. With Nouns 128 ii. With Verbs 130 2. Demonstrative Pronouns 132 3. 'Determinative-Relative-Indefinite Pronouns 133 4. Comparative Discussion 134 5. Possessive Pronoun 136 6. Interrogative Pronouns 136 7. Indefinite Pronoun 137 oi.uchicago.edu pages C. Nouns 137 1. Declension 137 a. Gender 137 b. Number 138 c. Case Endings- 139 d. -

The Gilgameš Epic at Ugarit

The Gilgameš epic at Ugarit Andrew R. George − London [Fourteen years ago came the announcement that several twelfth-century pieces of the Babylonian poem of Gilgameš had been excavated at Ugarit, now Ras Shamra on the Mediterranean coast. This article is written in response to their editio princeps as texts nos. 42–5 in M. Daniel Arnaud’s brand-new collection of Babylonian library tablets from Ugarit (Arnaud 2007). It takes a second look at the Ugarit fragments, and considers especially their relationship to the other Gilgameš material.] The history of the Babylonian Gilgameš epic falls into two halves that roughly correspond to the second and first millennia BC respectively. 1 In the first millennium we find multiple witnesses to its text that come exclusively from Babylonia and Assyria. They allow the reconstruction of a poem in which the sequence of lines, passages and episodes is more or less fixed and the text more or less stable, and present essentially the same, standardized version of the poem. With the exception of a few Assyrian tablets that are relics of an older version (or versions), all first-millennium tablets can be fitted into this Standard Babylonian poem, known in antiquity as ša naqba īmuru “He who saw the Deep”. The second millennium presents a very different picture. For one thing, pieces come from Syria, Palestine and Anatolia as well as Babylonia and Assyria. These fragments show that many different versions of the poem were extant at one time or another during the Old and Middle Babylonian periods. In addition, Hittite and Hurrian paraphrases existed alongside the Akkadian texts. -

Ninhursag Ninhursag 1 Ninhursag

נינורסג http://forums.nana10.co.il/Article/?ArticleID=166703 http://www.zarfatit.co.il/targum/Ninhursag Ninhursag 1 Ninhursag In Sumerian mythology, Ninhursag (ሪ ሰሧ ለ Ninḫursag) or Ninkharsag[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] was a mother goddess of the mountains, and one of the seven great deities of Sumer. She is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the 'true and great lady of heaven' (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were 'nourished by Ninhursag's milk'. Her hair is sometimes depicted in an omega shape, and she at times wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders, and not infrequently carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders. Names Nin-hursag means "lady of the sacred mountain" (from Sumerian NIN "lady" and ḪAR.SAG "sacred mountain, foothill", possibly a reference to the site of her temple, the E-Kur (House of mountain deeps) at Eridu. She had many names including Ninmah ("Great Queen"); Nintu ("Lady of Birth"); Mamma or Mami (mother); Aruru, Belet-Ili (lady of the gods, Akkadian) According to legend her name was changed from Ninmah to Ninhursag by her son Ninurta in order to commemorate his creation of the mountains. As Ninmenna, according to a Babylonian investiture ritual, she placed the golden crown on the king in the Eanna temple.Wikipedia:Citation needed Some of the names above were once associated with independent goddesses (such as Ninmah and Ninmenna), who later became identified and merged with Ninhursag, and myths exist in which the name Ninhursag is not mentioned.