Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Heritage.Pages

Heritage in Micronesia SPANISH PROGRAM FOR CULTURAL COOPERATION with the collaboration of the GUAM PRESERVATION TRUST and the HISTORIC RESOURCES DIVISION, DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION Spanish Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation Conference Spanish Heritage in Micronesia Inventory and Assessment October 16, 2008 Hyatt Regency, Tumon Guam Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation with the collaboration of the Guam Preservation Trust and the Historic Resources Division, Guam Department of Parks and Recreation Table of Contents Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment 1 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage Resources In The Mariana Islands 5 By Judith S. Flores, PhD The Archaeology of Spanish Period, Guam 11 By John A. Peterson Inventory and Assessment of Spanish Tangible Heritage in the Federated States of Micronesia 32 By Rufino Mauricio Heritage Preservation And Sustainability: Technical Recommendations And Community Participation 44 By Maria Lourdes Joy Martinez-Onozawa Historic Inalahan Field Workshop 52 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage in Palau 61 By Filly Carabit and Errolflynn Kloulechad Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment Introduction By Judith S. Flores, PhD President, Historic Inalahan Foundation, Inc. The second in a series of conferences funded by the Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation (SPCC) opened in the Hyatt-Regency in Tumon, Guam on October 16, 2008. The first conference sponsored by SPCC was held the previous year in Guam on Nov. 14-15, 2007, entitled “Stonework Heritage in Micronesia”, organized by the Guam Preservation Trust. It brought together and introduced technical experts in Spanish stonework and Spanish heritage architects to a gathering of historic preservation officials and scholars who live and work in Guam and Micronesia. -

The Royal African: Or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com THE Royal African? MEMO IRS ; OF THE Young Prince of Annamaboe. Comprehending A distinct Account of his Country and Family ; his elder Brother's Voyage to France, and Recep tion there ; the Manner in which himself was confided by his Father to the Captain who sold him ; his Condition while a Slave in Barbadoes ; the true Cause of his being redeemed ; his Voy age from thence; and Reception here in England. Interspers'd throughout / 4 With several Historical Remarks on the Com merce of the European Nations, whose Subjects fre quent the Coast of Guinea. To which is prefixed A LETTER from thdr; Author to a Person of Distinction, in Reference to some natural Curiosities in Africa ; as well as explaining the Motives which induced him to compose these Memoirs. — . — — t Othello shews the Muse's utmost Power, A brave, an honest, yet a hapless Moor. In Oroonoko lhines the Hero's Mind, With native Lustre by no Art resin 'd. Sweet Juba strikes us but with milder Charms, At once renown'd for Virtue, Love, and Arms. Yet hence might rife a still more moving Tale, But Shake/pears, Addisons, and Southerns fail ! LONDON: Printed for W. Reeve, at Sha&ejpear's Head, Flectsireet ; G. Woodfall, and J. Barnes, at Charing- Cross; and at the Court of Requests. /: .' . ( I ) To the Honourable **** ****** Qs ****** • £#?*, Esq; y5T /j very natural, Sir, /£æ/ ><?a should be surprized at the Accounts which our News- Papers have given you, of the Appearance of art African Prince in England under Circumstances of Distress and Ill-usage, which reflecl very highly upon us as a People. -

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18Th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research Creative Activity - Documents and Creativity 4-21-2010 Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buckwalter, James, "Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century" (2010). 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research and Creativity at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James Buckwalter Booth Library Research Award Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century My research has focused on slave insurrections on board British ships in the early 18th century and their perceptions both in government and social circles. In all, it uncovers the stark differences in attention given to shipboard insurrections, ranging from significant concern in maritime circles to near ignorance in government circles. Moreover, the nature of discourse concerning slave shipboard insurrections differs from Britons later in the century, when British subjects increasingly began to view the slave trade as not only morally reprehensible, but an area in need of political reform as well. -

The Alcoholic Republic

THE ALCOHOLIC REPUBLIC AN AMERICAN TRADITION w. J. RORABAUGH - . - New York Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1979 THE GROG-SHOP o come le t us all to the grog- shop: The tempest is gatheri ng fa st- The re sure lyis nought li ke the grog- shop To shield fr om the turbulent blast. For there will be wrangli ng Wi lly Disputing about a lame ox; And there will be bullyi ng Billy Challengi ng negroes to box: Toby Fillpot with carbuncle nose Mixi ng politics up with his li quor; Ti m Tuneful that si ngs even prose, And hiccups and coughs in hi s beaker. Dick Drowsy with emerald eyes, Kit Crusty with hair like a comet, Sam Smootly that whilom grewwise But returned like a dog to his vomit And the re will be tippli ng and talk And fuddling and fu n to the lif e, And swaggering, swearing, and smoke, And shuffling and sc uffling and strife. And there will be swappi ng ofhorses, And betting, and beating, and blows, And laughter, and lewdness, and losses, And winning, and wounding and woes. o the n le t us offto the grog- shop; Come, fa ther, come, jonathan, come; Far drearier fa r than a Sunday Is a storm in the dull ness ofhome . GREEN'S ANTI-INTEMPERANCE ALMANACK (1831) PREFACE THIS PROJECT began when I discovered a sizeable collec tion of early nineteenth-century temperance pamphlets. As I read those tracts, I wondered what had prompted so many authors to expend so much effort and expense to attack alcohol. -

Enlightenment Implications, Bourbon Influence and Character

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive Enlightenment Implications, Bourbon Influence and Character Construction in Comedia nueva del apostolado en las Indias martirio de un cacique: An Alternative Approach to the Life, Works and Ideology of Eusebio Vela By Megan Louise Oleson Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Latin American Studies August 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Ruth Hill, Ph.D. José Cárdenas-Bunsen, Ph.D. To Panama, Eric, Mom, Dad, Erica and the rest of my family and friends. Your love and support made this all possible. ii First and foremost, without the funding provided by the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship, none of this would have been possible. The completion of this project is a product of the guidance and support of the faculty associated with the Latin American Studies Department and the faculty of the Spanish and Portuguese Department. I would like to give a special thanks to my advisor Professor Ruth Hill for her continuous encouragement. Her knowledge and appreciation for the subject are inspirational and infectious. Professor José Cárdenas-Bunsen aided in bringing together the final components of my thesis and I am thankful for his insightful comments and his innate optimism. Alma Paz- Sanmiguel has been instrumental in many other aspects of my graduate school experience and for that I will be forever grateful. Last but not least, the daily support of my partner Eric and our daughter Panama has been fundamental in attaining my Master’s degree. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

John R. Mcneill University Professor Georgetown University President of the American Historical Association, 2019 Presidential Address

2020-President_Address.indd All Pages 14/10/19 7:31 PM John R. McNeill University Professor Georgetown University President of the American Historical Association, 2019 Presidential Address New York Hilton Trianon Ballroom New York, New York Saturday, January 4, 2020 5:30 PM John R. McNeill By George Vrtis, Carleton College In fall 1998, John McNeill addressed the Georgetown University community to help launch the university’s new capital campaign. Sharing the stage with Georgetown’s president and other dignitaries, McNeill focused his comments on the two “great things” he saw going on at Georgetown and why each merited further support. One of those focal points was teaching and the need to constantly find creative new ways to inspire, share knowledge, and build intellectual community among faculty and students. The other one centered on scholarship. Here McNeill suggested that scholars needed to move beyond the traditional confines of academic disciplines laid down in the 19th century, and engage in more innovative, imaginative, and interdisciplinary research. Our intellectual paths have been very fruitful for a long time now, McNeill observed, but diminishing returns have set in, information and methodologies have exploded, and new roads beckon. To help make his point, McNeill likened contemporary scholars to a drunk person searching for his lost keys under a lamppost, “not because he lost them there but because that is where the light is.” The drunk-swirling-around-the-lamppost metaphor was classic McNeill. Throughout his academic life, McNeill has always conveyed his ideas in clear, accessible, often memorable, and occasionally humorous language. And he has always ventured into the darkness, searchlight in hand, helping us to see and understand the world and ourselves ever more clearly with each passing year. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

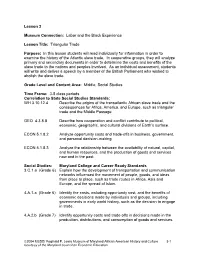

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

1 LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10

LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10 (3-6 p.m.), Keene-Flint 13 Office: Grinter Rm. 339 Email: [email protected] Hours: Th 10-12 The objective of the seminar is to become familiar with trends and topics in the history and historiography of early Spanish America. The field has grown rapidly in recent years, and earlier pioneering work has not been superseded. Our approach will take into account the development of the scholarship and changing emphases in topics, sources and methodology. For each session there are readings for discussion, listed under the weekly topic. These are mostly journal articles or book chapters. You will write short (2-3 pages) response papers on assigned readings as well as introducing them and suggesting questions for discussion. For each week’s topic a number of books are listed. You should become familiar with most of this literature if colonial Spanish America is a field for your qualifying exams. Each student will write two book reviews during the semester, to be chosen from among the books on the syllabus (or you may suggest one). The final paper (12-15 pages in length) is due on the last day of class. If you write a historiographical paper it should focus on the most important work on the topic rather than being bibliographic. You are encouraged to read in Spanish as well as English. For a fairly recent example of a historiographical essay, see R. Douglas Cope, “Indigenous Agency in Colonial Spanish America,” Latin American Research Review 45:1 (2010). You also may write a research paper. -

Bulletin Vol

american academy of arts & sciences winter 2006 Bulletin vol. lix, no. 2 Page 1 American Academy Welcomes the 225th Class of Members Page 2 Exhibit from the Archives Members’ Letters of Acceptance Page 26 Concepts of Justice Essays by Alan Brinkley, Kathleen M. Sullivan, Geoffrey Stone, Patricia M. Wald, Charles Fried, and Kim Lane Scheppele inside: Projects and Studies, Page 15 Visiting Scholars Program, Page 24 New Members: Class of 2005, Page 42 From the Archives, Page 60 Calendar of Events Thursday, Saturday, February 9, 2006 March 18, 2006 Stated Meeting–Cambridge Stated Meeting–San Francisco “Tax Reform: Current Problems, Possible “Innovation: The Creative Blending of Art Contents Solutions, and Unresolved Questions” and Science” Speaker: James Poterba, mit Speaker: George Lucas, Lucas½lm Ltd. Academy News Introduction and Response: Michael J. Introduction: F. Warren Hellman, Graetz, Yale University Hellman & Friedman, LLC Academy Inducts 225th Class 1 Location: House of the Academy Location: Letterman Digital Arts Center, The Presidio of San Francisco Major Funding from the Mellon Time: 6:00 p.m. Foundation 1 Time: 5:00 p.m. Exhibit from the Academy’s Archives 2 Wednesday, February 15, 2006 Tuesday, April 4, 2006 Challenges Facing the Regional Meeting–Chicago Intellectual Community 7 Stated Meeting and Joint Meeting with “America’s Greatest Lawyer: Abraham Lincoln the Boston Athenæum–Boston in Private Practice and Public Life” Projects and Studies 15 “Great Scienti½c Discoveries of the Twentieth Speaker: Walter E. Dellinger, Century” Duke University Visiting Scholars Program 24 Speaker: Alan Lightman, mit Introduction: Saul Levmore, Academy Lectures University of Chicago Law School Location: Boston Athenæum Location: University of Chicago Law School Time: 6:00 p.m.