The Complete Acoustic and Electric Guitar Pac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

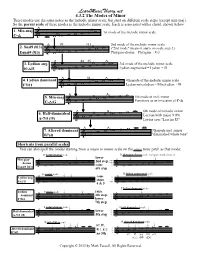

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic Structure of Triads

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic structure of Triads Another name of an interval is a “dyad” (two pitches). If two successive intervals (3 notes) happen simultaneously, we now have what is referred to as a chord or a “triad” (three pitches) Major and Minor Triads A Major triad consists of a M3 and a P5 interval from the root. A minor triad consists of a m3 and a P5 interval from the root. Diminished and Augmented Triads A diminished triad consists of a m3 and a dim 5th interval from the root. An augmented triad consists of a M3 and an Aug 5th interval from the root. The augmented triad has a major third interval and an augmented fifth interval from the root. An augmented triad differs from a major triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step higher than it is in the major triad. The diminished triad differs from minor triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step lower than it is in the minor triad. Recommended process: 1. Memorize your Perfect 5th intervals from most root pitches (ex. A-E, B-F#, C-G, D-A, etc…) 2. Know that a Major 3rd interval is two whole steps from a root pitch If you can identify a M3 and P5 from a root, you will be able to correctly spell your Major Triads. 3. If you need to know a minor triad, adjust the 3rd of the major triad down a half step to make it minor. 4. If you need to know an Augmented triad, adjust the 5th of the chord up a half step from the MAJOR triad. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Proquest Dissertations

A comparison of embellishments in performances of bebop with those in the music of Chopin Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mitchell, David William, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:23:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278257 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the miaofillm master. UMI films the text directly fi^om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contLDuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

The Strategic Half-Diminished Seventh Chord and the Emblematic Tristan Chord: a Survey from Beethoven to Berg

International Journal ofMusicology 4 . 1995 139 Mark DeVoto (Medford, Massachusetts) The Strategic Half-diminished Seventh Chord and The Emblematic Tristan Chord: A Survey from Beethoven to Berg Zusammenfassung: Der strategische halbverminderte Septakkord und der em blematische Tristan-Akkord von Beethoven bis Berg im Oberblick. Der halb verminderte Septakkord tauchte im 19. Jahrhundert als bedeutende eigen standige Hannonie und als Angelpunkt bei der chromatischen Modulation auf, bekam aber eine besondere symbolische Bedeutung durch seine Verwendung als Motiv in Wagners Tristan und Isolde. Seit der Premiere der Oper im Jahre 1865 lafit sich fast 100 Jahre lang die besondere Entfaltung des sogenannten Tristan-Akkords in dramatischen Werken veifolgen, die ihn als Emblem fUr Liebe und Tod verwenden. In Alban Bergs Lyrischer Suite und Lulu erreicht der Tristan-Akkord vielleicht seine hOchste emblematische Ausdruckskraft nach Wagner. If Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in general, and its Prelude in particular, have stood for more than a century as the defining work that liberated tonal chro maticism from its diatonic foundations of the century before it, then there is a particular focus within the entire chromatic conception that is so well known that it even has a name: the Tristan chord. This is the chord that occurs on the downbeat of the second measure of the opera. Considered enharmonically, tills chord is of course a familiar structure, described in many textbooks as a half diminished seventh chord. It is so called because it can be partitioned into a diminished triad and a minor triad; our example shows it in comparison with a minor seventh chord and an ordinary diminished seventh chord. -

Fully-Diminished Seventh Chords Introduction

Lesson PPP: Fully-Diminished Seventh Chords Introduction: In Lesson 6 we looked at the diminished leading-tone triad: vii o. There, we discussed why the tritone between the root and fifth of the chord requires special attention. The chord usually appears in first inversion precisely to avoid that dissonant interval sounding against the bass when vii o is in root position. Example 1: As Example 1 demonstrates, placing the chord in first inversion ensures that the upper voices are consonant with the bass. The diminished fifth is between the alto and soprano, concealed within the upper voices. In this case, it is best understood as a resultant interval formed as a result of avoiding dissonances involving the bass. Adding a diatonic seventh to a diminished leading-tone triad in minor will result in the following sonority: Example 2: becomes This chord consists of a diminished triad with a diminished seventh added above the root. It is therefore referred to as a fully-diminished seventh chord. In this lesson, we will discuss the construction of fully-diminished seventh chords in major and minor keys. As you will see, the chord consists of two interlocking tritones, which require particularly careful treatment because of their strong voice-leading tendencies. We will consider its various common functions and will touch on several advanced uses of the chord as well. Construction: Fully-diminished leading-tone seventh chords can be built in major or minor keys. In Roman numeral analyses, they are indicated with a degree sign followed by seventh-chord figured bass numerals, o7 o 6 o 4 o 4 depending on inversion ( , 5 , 3 , or 2 ). -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

Towards a Generative Framework for Understanding Musical Modes

Table of Contents Introduction & Key Terms................................................................................1 Chapter I. Heptatonic Modes.............................................................................3 Section 1.1: The Church Mode Set..............................................................3 Section 1.2: The Melodic Minor Mode Set...................................................10 Section 1.3: The Neapolitan Mode Set........................................................16 Section 1.4: The Harmonic Major and Minor Mode Sets...................................21 Section 1.5: The Harmonic Lydian, Harmonic Phrygian, and Double Harmonic Mode Sets..................................................................26 Chapter II. Pentatonic Modes..........................................................................29 Section 2.1: The Pentatonic Church Mode Set...............................................29 Section 2.2: The Pentatonic Melodic Minor Mode Set......................................34 Chapter III. Rhythmic Modes..........................................................................40 Section 3.1: Rhythmic Modes in a Twelve-Beat Cycle.....................................40 Section 3.2: Rhythmic Modes in a Sixteen-Beat Cycle.....................................41 Applications of the Generative Modal Framework..................................................45 Bibliography.............................................................................................46 O1 O Introduction Western -

The Death and Resurrection of Function

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF FUNCTION A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Miller, B.A., M.C.M., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Gregory Proctor, Advisor Dr. Graeme Boone ________________________ Dr. Lora Gingerich Dobos Advisor Graduate Program in Music Copyright by John Gabriel Miller 2008 ABSTRACT Function is one of those words that everyone understands, yet everyone understands a little differently. Although the impact and pervasiveness of function in tonal theory today is undeniable, a single, unambiguous definition of the term has yet to be agreed upon. So many theorists—Daniel Harrison, Joel Lester, Eytan Agmon, Charles Smith, William Caplin, and Gregory Proctor, to name a few—have so many different nuanced understandings of function that it is nearly impossible for conversations on the subject to be completely understood by all parties. This is because function comprises at least four distinct aspects, which, when all called by the same name, function , create ambiguity, confusion, and contradiction. Part I of the dissertation first illuminates this ambiguity in the term function by giving a historical basis for four different aspects of function, three of which are traced to Riemann, and one of which is traced all the way back to Rameau. A solution to the problem of ambiguity is then proposed: the elimination of the term function . In place of function , four new terms—behavior , kinship , province , and quality —are invoked, each uniquely corresponding to one of the four aspects of function identified. -

A Transformational Approach to Jazz Harmony

A TRANSFORMATIONAL APPROACH TO JAZZ HARMONY Michael McClimon Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University January 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee Julian Hook, Ph.D. Kyle Adams, Ph.D. Blair Johnston, Ph.D. Brent Wallarab, M.M. December 9, 2015 ii Copyright © 2016 Michael McClimon iii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the help of many others, each of whom deserves my thanks here. Pride of place goes to my advisor, Jay Hook, whose feedback has been invaluable throughout the writing process, and whose writing stands as a model of clarity that I can only hope to emulate. Thanks are owed to the other members of my committee as well, who have each played important roles throughout my education at Indiana: Kyle Adams, Blair Johston, and Brent Wallarab. Thanks also to Marianne Kielian-Gilbert, who would have served on the committee were it not for the timing of the defense during her sabbatical. I would like to extend my appreciation to Frank Samarotto and Phil Ford, both of whom have deeply shaped the way I think about music, but have no official role in the dissertation itself. I am grateful to the music faculty of Furman University, who inspired my love of music theory as an undergraduate and have more recently served as friends and colleagues during the writing process. -

Pemetaan Pola Progresi Chord Berdasarkan Kombinasi Interval

Pemetaan Pola Progresi Chord Berdasarkan Kombinasi Interval Ilham Pamuji Institut Seni Budaya Indonesia (ISBI) Bandung Jl. Buah-Batu No.212, Cijagra, Lengkong, Kota Bandung 40265 [email protected] ABSTRACT Various phenomena, concepts and theories in music can be explained by mathematics. Moreover, it can be an approach in the process of song creation, composition, or music arrangement. Related to this, this study discusses the mapping of chord progressions based on interval combinations in chromatic circles. To be more specific, by connecting the musical notes with lines that represent various combinations of two specific types of intervals into a series of notes (chord progression patterns) in one loop ( starts and ends at note C). The interval combination pattern refers to the smallest size, namely m2 (minor second /minor second, 1 semitone step). This research was conducted to produce various patterns of unconventional chord progression patterns viewed through a tonal harmony system. This research is motivated by the strong influence of the tonal harmony system limiting creativity in the music creation process. Therefore, it takes an approach, method, or other system that needs to be tested to get out of the system. The result of this research is that there are 32 variations of chord progression patterns (series of notes) which are summarized in geometric shapes. By comparing the geometric shapes, the patterns appear mathematically, systematic, and symmetrical. In its application, these patterns seem unconventional, come out of a tonal harmony system (it can still be studied through the system, depending on the chord shape used) and produce a unique sound. Keywords: chord progression, interval, chromatic circle, music creation PENDAHULUAN matematis pada unsur atau formula A. -

Cultivating the Antecedents of Barry Harris’ Concept of Movement As a Multidimensional Pedagogical Tool for Ontario Post-Secondary Jazz Curricula

REANIMATING DISSONANCE: CULTIVATING THE ANTECEDENTS OF BARRY HARRIS’ CONCEPT OF MOVEMENT AS A MULTIDIMENSIONAL PEDAGOGICAL TOOL FOR ONTARIO POST-SECONDARY JAZZ CURRICULA BRIAN JUDE DE LIMA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2017 © Brian Jude de Lima, 2017 Abstract ii One of the challenges faced in post-secondary jazz education across the GTA is finding qualified instructors who are familiar with dialogical methods for teaching African American jazz histories. More specifically, finding and hiring African American instructors whose musical genealogy can be delineated from “black” oral/aural histories and can draw from these historicities. Unless the narratives of this music are unpacked, analyzed and taught from its internal elements, which embodies the symbiosis and synthesis of African American dance, theatrics, poetics and American black English that encapsulates the “African American-ness” in jazz, then there remains a risk that this folk music will become more and more diluted. Consequently, it is my belief that current music educators across the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) should consider alternative methods of pedagogy if students are to understand the historicity— the historical authenticity of this African American folk music. The idea for this study originated from my observation of a lack of “African American- ness”—African American narratives not being used as a pedagogical tool in post-secondary jazz curricula across the GTA. Therefore, this multi-case study will lead to the creation of an alternative curriculum that incorporates new teaching methods based on African American narratives.