At Mbeya Hosea Kasumo Mwakasitu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kenya Power & Lighting Company Plc Half-Year Financial Statements 31

THE KENYA POWER & LIGHTING COMPANY PLC HALF-YEAR FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 DECEMBER 2020 THE KENYA POWER & LIGHTING COMPANY PLC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR SIX MONTHS PERIOD ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS PAGES Report of the Directors 2 Statement of Comprehensive Income 3 Statement of Financial Position 4 Statement of Changes in Equity 5 Statement of Cash Flows 6 Notes to the Financial Statements 7 - 22 1 THE KENYA POWER & LIGHTING COMPANY PLC REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS The Directors submit the unaudited interim financial statements for the six months’ period ended 31 December 2020 ACTIVITIES The core business of the Company continues to be the transmission, distribution and retail of electricity purchased in bulk from The Kenya Electricity Generating Company Limited (KenGen), Independent Power Producers (IPPs), Uganda Electricity Transmission Company (UETCL) and Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO). RESULTS Shs’000 Profit before Taxation 332,658 Taxation charge (194,297) Profit for the Period 138,361 DIVIDENDS The Directors recommend no payment of interim dividend for the period. 2 THE KENYA POWER & LIGHTING COMPANY PLC STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME FOR THE SIX MONTHS PERIOD ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 Note 31.12.2020 31.12.2019 Revenue Shs’ 000 Shs’ 000 Electricity Sales 2 (a) 61,497,156 61,241,134 Foreign Exchange adjustment 2 (a) 2,662,375 571,532 Fuel cost adjustment 2 (a) 4,855,056 7,793,993 69,014,587 69,606,659 Power Purchase Costs Non Fuel Power Purchase Costs 3 (a) (38,122,496) (37,190,151) Foreign -

Annual Report 2019 East African Development Bank

Your partner in development ANNUAL REPORT 2019 EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 2 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK CORPORATE PROFILE OF EADB Uganda (Headquarters) Plot 4 Nile Avenue EADB Building P. O. Box 7128 Kampala, Uganda Kenya Country office, Kenya 7th Floor, The Oval Office, Ring Road, Rwanda REGISTERED Parklands Westland Ground Floor, OFFICE AND P.O. Box 47685, Glory House Kacyiru PRINCIPAL PLACE Nairobi P.O. Box 6225, OF BUSINESS Kigali Rwanda Tanzania 349 Lugalo/ Urambo Street Upanga P.O. Box 9401 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania BANKERS Uganda (Headquarters) Standard Chartered –London Standard Chartered – New York Standard Chartered - Frankfurt Citibank – London Citibank – New York AUDITOR Standard Chartered – Kampala PricewaterhouseCoopers Stanbic – Kampala Certified Public Accountants, Citibank – Kampala 10th Floor Communications House, 1 Colville Street, Kenya P.O. Box 882 Standard Chartered Kampala, Uganda Rwanda Bank of Kigali Tanzania Standard Chartered 4 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ESTABLISHMENT The East African Development Bank (EADB) was established in 1967 SHAREHOLDING The shareholders of the EADB are Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda. Other shareholders include the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO), German Investment and Development Company (DEG), SBIC-Africa Holdings, NCBA Bank Kenya, Nordea Bank of Sweden, Standard Chartered Bank, London, Barclays Bank Plc., London and Consortium of former Yugoslav Institutions. MISSION VISION OUR CORE To promote sustain- To be the partner of VALUES able socio-economic choice in promoting development in East sustainable socio-eco- Africa by providing nomic development. -

Absa Bank 22

Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 2020 Promoting Partnerships Transforming Banking Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 3 Content About Uganda 6 Bankers' Association UBA Structure and 9 Governance UBA Member 10 Bank CEOs 15 UBA Executive Committee 2020 16 UBA Secretariat Management Team UBA Committee 17 Representatives 2020 Content Message from the 20 UBA Chairman Message from the 40 Executive Director UBA Activities 42 2020 CSR & UBA Member 62 Bank Activities Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 70 December 2020 5 About Uganda Bankers' Association Commercial 25 banks Development 02 Banks Tier 2 & 3 Financial 09 Institutions ganda Bankers’ Association (UBA) is a membership based organization for financial institutions licensed and supervised by Bank of Uganda. Established in 1981, UBA is currently made up of 25 commercial banks, 2 development Banks (Uganda Development Bank and East African Development Bank) and 9 Tier 2 & Tier 3 Financial Institutions (FINCA, Pride Microfinance Limited, Post Bank, Top Finance , Yako Microfinance, UGAFODE, UEFC, Brac Uganda Bank and Mercantile Credit Bank). 6 • Promote and represent the interests of the The UBA’s member banks, • Develop and maintain a code of ethics and best banking practices among its mandate membership. • Encourage & undertake high quality policy is to; development initiatives and research on the banking sector, including trends, key issues & drivers impacting on or influencing the industry and national development processes therein through partnerships in banking & finance, in collaboration with other agencies (local, regional, international including academia) and research networks to generate new and original policy insights. • Develop and deliver advocacy strategies to influence relevant stakeholders and achieve policy changes at industry and national level. -

Bank Supervision Annual Report 2019 1 Table of Contents

CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION STATEMENT VII THE BANK’S MISSION VII MISSION OF BANK SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT VII THE BANK’S CORE VALUES VII GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE IX FOREWORD BY DIRECTOR, BANK SUPERVISION X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XII CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 1.1 The Banking Sector 2 1.2 Ownership and Asset Base of Commercial Banks 4 1.3 Distribution of Commercial Banks Branches 5 1.4 Commercial Banks Market Share Analysis 5 1.5 Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) 7 1.6 Asset Base of Microfinance Banks 7 1.7 Microfinance Banks Market Share Analysis 9 1.8 Distribution of Foreign Exchange Bureaus 11 CHAPTER TWO DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING SECTOR 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Banking Sector Charter 13 2.3 Demonetization 13 2.4 Legal and Regulatory Framework 13 2.5 Consolidations, Mergers and Acquisitions, New Entrants 13 2.6 Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) Support 14 2.7 Developments in Information and Communication Technology 14 2.8 Mobile Phone Financial Services 22 2.9 New Products 23 2.10 Operations of Representative Offices of Authorized Foreign Financial Institutions 23 2.11 Surveys 2019 24 2.12 Innovative MSME Products by Banks 27 2.13 Employment Trend in the Banking Sector 27 2.14 Future Outlook 28 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA 2 BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE 3.1 Global Economic Conditions 30 3.2 Regional Economy 31 3.3 Domestic Economy 31 3.4 Inflation 33 3.5 Exchange Rates 33 3.6 Interest -

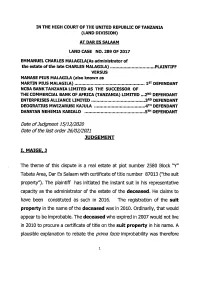

Date O F Judgment 15/12/2020 Date O F the Last Order 26/02/2021

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA (LAND DIVISION) AT PAR ES SALAAM LAND CASE NO. 289 OF 2017 EMMANUEL CHARLES MALAGILA(As administrator of the estate of the late CHARLES MALAGILA)....................................PLAINTIFF VERSUS MANASE PIUS MALAGILA (also known as MARTIN PIUS MALAGILA)......................................................... 1st DEFENDANT NCBA BANK TANZANIA LIMITED AS THE SUCCESSOR OF THE COMMERCIAL BANK OF AFRICA (TANZANIA) LIMITED ...2nd DEFENDANT ENTERPRISES ALLIANCE LIMITED.... ...................................... 3rd DEFENDANT DEOGRATIUS MWIZARUBI KAJULA .........................................4th DEFENDANT DANSTAN NEHEMIA KABIALO .................................................5™ DEFENDANT Date o fJudgment 15/12/2020 Date o f the last order 26/02/2021 JUDGEMENT I. MAIGE. J The theme of this dispute is a real estate at plot number 2580 Block "Y" Tabata Area, Dar Es Salaam with certificate of title number 87013 ("the suit property7'). The plaintiff has initiated the instant suit in his representative capacity as the administrator of the estate of the deceased. He claims to have been constituted as such in 2016. The registration of the suit property in the name of the deceased was in 2010. Ordinarily, that would appear to be improbable. The deceased who expired in 2007 would not live in 2010 to procure a certificate of title on the suit property in his name. A plausible explanation to rebate the prima facie improbability was therefore i inevitable. In his pleadings and evidence/ it would appear, the plaintiff has attempted to give an account therefor. This is a very pertinent fact in determining the dispute. The plaintiff claims that the suit property while still un-surveyed, was acquired by the deceased way back in 1992 and it had since then been in his occupation. -

Co-Operatives and Fair-Trade

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN Co-operatives and Fair-Trade Background paper commissioned by the Committee for the Promotion and Advancement of Cooperatives (COPAC) for the COPAC Open Forum on Fair Trade and Cooperatives, Berlin (Germany) Patrick Develtere Ignace Pollet February 2005 Higher Institute of Labour HIVA ‐ Higher Institute for Labour Studies Parkstraat 47 3000 Leuven Belgium tel. +32 (0) 16 32 33 33 fax. + 32 (0) 16 32 33 44 www.hiva.be COPAC ‐ Committee for the Promotion and Advancement of Co‐operatives 15, route des Morillons 1218 Geneva Switzerland tel. +41 (0) 22 929 8825 fax. +41 (0) 22 798 4122 www.copacgva.org iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 What is fair-trade? What is co-operative trade? What do both have in common? 2 1. Fair-trade: definition and criteria 2 2. Roots and related concepts 6 3. Actual significance of fair-trade 8 4. Fair-trade and co-operative trade 9 4.1 Where do co-operatives enter the scene? 9 4.2 Defining co-operatives 10 4.3 Comparing co-operative and fair-trade movement: the differences 11 4.4 Comparing the co-operative and fair-trade movement: communalities 13 2. Involvement of co-operatives in practice 14 2.1 In the South: NGOs and producers co-operatives 15 2.2 Co-operatives involved with fair-trade in the North 16 3. Co-operatives and Fair-trade: a fair deal? 19 3.1 Co-operatives for more fair-trade? 19 3.2 Fair-trade for better co-operatives? 20 4. What happens next? Ideas for policy 22 Bibliographical references 25 1 INTRODUCTION This paper is meant to provide a first insight into an apparently new range of activities of the co-operative movement: fair-trade activities. -

Social Cap and Membership in Dairy Co-Ops in Kenya

Running Head: SOCIAL CAP AND MEMBERSHIP IN DAIRY CO-OPS IN KENYA Social Capital and Membership in Dairy Cooperatives in Kenya _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by REBECCA SAVOIE Dr. David O’Brien, Dissertation Supervisor December 2018 SOCIAL CAP AND MEMBERSHIP IN DAIRY CO-OPS IN KENYA © Copyright by Rebecca Savoie 2018 All Rights Reserved SOCIAL CAP AND MEMBERSHIP IN DAIRY CO-OPS IN KENYA The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled Social Capital and Membership in Dairy Cooperatives in Kenya presented by Rebecca Savoie a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor David O’Brien Professor Mary Hendrickson Professor Jere Gilles Professor Michael Cook SOCIAL CAP AND MEMBERSHIP IN DAIRY CO-OPS IN KENYA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Mildred Rother, who passed away during the course of my PhD. I have never known a more persevering woman, whose wisdom, kindness and love have flowed down the generations to my mother, Jean Savoie, and to my daughter, Amina Savoie. How blessed I am to be surrounded by these amazing people. I would like to first thank the fine team at Land O’Lakes International Development, where during my tenure managing their Cooperative Development Program, I met Dr. Cook and Dr. O’Brien. I would also like to thank my current employer, NCBA CLUSA, for the flexibility afforded during the past year. -

East Africa's Family-Owned Business Landscape

EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS LANDSCAPE 500 LEADING COMPANIES ACROSS THE REGION PREMIUM SPONSORS: 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS CONTENTS LANDSCAPE Co-Founder, CEO 3 Executive Summary Rob Withagen 4 Methodology Co-Founder, COO Greg Cohen 7 1. MARKET LANDSCAPE Project Director 8 Regional Heavyweight: East Africa Leads Aicha Daho Growth Across the Continent Content Director 10 Come Together: Developing Intra- Jennie Forcier Patterson Regional Trade Opens Markets of Data Director Significant Scale Yusra Khadra 11 Interview: Banque du Caire Editorial Manager Lauren Mellows 13 2. FOB THEMES Research & Data Team Alexandria Akena 14 Stronger Together: Private Equity Jerome Amedo Offers Route to Growth for Businesses Laban Bore Prepared to Cede Some Ownership Jessen Chiniven Control Woyneab Habte Mayowa Hambolu 15 Interview: Centum Investment Milkiyas Lekeleh Siyum 16 Interview: Nairobi Securities Exchange Omololu Adeniran 17 A Hire Calling: Merit is Becoming a Medina Mamadou Stronger Factor in FOB Employment Kuringe Masao Melina Matabishi Practices Ivan Matoowa 18 Interview: Anjarwalla & Khanna Sweetness Mathew 21 Interview: CDC Group Plc Paige Arhaus Theodore Angwenyi 22 Interview: Melvin Marsh International Design 23 Planning for the Future: Putting Next- Nuno Caldeira Generation Leaders at the Helm 24 Interview: Britania Allied Industries 25 3. COUNTRY DEEPDIVES 25 Kenya 45 Ethiopia 61 Uganda 77 Tanzania 85 Rwanda 91 4. FOB DIRECTORY EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS LANDSCAPE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE -

Tanzania Mortgage Market Update – 31 December 2020

TANZANIA MORTGAGE MARKET UPDATE – 31 DECEMBER 2020 1. Highlights The mortgage market in Tanzania registered a 6 percent annual growth in the value of mortgage loans from 31 December 2019 to 31 December 2020. On a quarter to quarter basis; the mortgage market in Tanzania registered a 4 percent growth in the value of mortgage loans as at 31 December 2020 compared to previous quarter which ended on 30 September 2020. There was no new entrant into the mortgage market during the quarter. The number of banks reporting to have mortgage portfolios increased from 31 banks to 32 banks recorded in Q4 2020 due to reporting to BOT by Mwanga Hakika Bank the newly formed bank after merger of Mwanga Community Bank, Hakika Microfinance Bank and EFC Microfinance Bank. EFC Microfinance bank did not report in Q3-2020 due to revocation of their licence after the merger and the newly formed bank reported for the first time in Q4-2020. Outstanding mortgage debt as at 31 December 2020 stood at TZS 464.14billion1 equivalent to US$ 200.93 million compared to TZS 445.21 billion equivalent to US$ 192.81 as at 30 September 2020. Average mortgage debt size was TZS 78.56 million equivalent to US$ 34,010 (TZS 76.67 million [US$ 33,203] as at 30 September 2020). The ratio of outstanding mortgage debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased to 0.30 percent compared to 0.28 percent recorded for the quarter ending 30 September 2020. Mortgage debt advanced by top 5 Primary Mortgage Lenders (PMLs) remained at 69 percent of the total outstanding mortgage debt as recorded in the previous quarter. -

How Co-Operatives Cope a Survey of Major Co-Operative Development Agencies

Development Co-operation: How Co-operatives Cope A survey of major co-operative development agencies Ignace Pollet Patrick Develtere A survey commissioned by: 1 Ignace Pollet Leuven, December 2003 Patrick Develtere PREFACE This study deals with development by co-operation and through co-operatives. Cera and the Belgian Raiffeisen Foundation (BRS) are very interested in this particular issue. Indeed, together they form the social arm of Cera, a dynamic co- operative group with 450,000 members, with a tradition stretching back more than one hundred years, and a passion for further developing and promoting the co-operative model. It is on the foundation of this interest and background that Cera and BRS have commissioned the Hoger Instituut voor de Arbeid (HIVA) [Higher Institute for Labour Studies] to carry out a survey of co-operative development agencies. This report is the result of that survey. Ignace Pollet and Patrick Develtere, both connected with the HIVA, discuss the following topics in this publication: (1) the renewed interest in co-operative development, (2) an historical view on co-operatives and development, and (3) a survey of ‘co-operative to co-operative, North to South’. The input of various national and international partners, above all regarding the provision of information, has made a considerable contribution to this study. 3 Based on this, the two authors have succeeded in producing a powerful analysis, and an easy-to-read and well-structured report. The authors have gone beyond simply making an inventory of that which exists in the field of co-operative development. In a fascinating analysis, they discuss the strong points and the challenges of the co-operative model for development. -

Page Tit Anglais

Contents I International Labour Conference 89th Session 2001 Report V (1) Promotion of cooperatives job creation in small and medium-sized enterprises Fifth item on the agenda International Labour Office Geneva II Promotion of cooperatives ISBN 92-2-111957-2 ISSN 0074-6681 First published 2000 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. ILO publications can be obtained through major booksellers or ILO local offices in many countries, or direct from ILO Publications, International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. A catalogue or list of new publications will be sent free of charge from the above address. Printed in Switzerland ATA Contents III CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER I: Cooperatives towards the twenty-first century . 5 1. The changing environment in which cooperatives operate . 5 1.1. Developments over the past 30 years which may warrant reconsidering the contents and structure of Recommendation No. 127 . 5 1.2. Developing countries . 11 1.2.1. The changing role of the State . 11 1.2.2. Economic effects . 14 1.2.3. -

Empowering Smallholder Farmers in Markets: Changing Agricultural Marketing Systems and Innovative Responses by Producer Organizations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Empowering Smallholder Farmers in Markets: Changing agricultural marketing systems and innovative responses by producer organizations Gideon Onumah and Junior Davis and Ulrich Kleih and Felicity Proctor Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich September 2007 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/25984/ MPRA Paper No. 25984, posted 23. October 2010 13:42 UTC ESFIM Working Paper 2 Empowering Smallholder Farmers in Markets: Changing Agricultural Marketing Systems and Innovative Responses by Producer Organizations Gideon E. Onumah, Junior R. Davis, Ulrich Kleih and Felicity J. Proctor [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] [email protected] September 2007 Table of contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................2 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................2 1.2 Context.................................................................................................................2 1.3 Structure of paper.................................................................................................3 2. Agricultural marketing systems in developing countries.......................................4 2.1 Evolution of the agricultural markets ..................................................................4