Disasters in Art by Sarah Wallin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

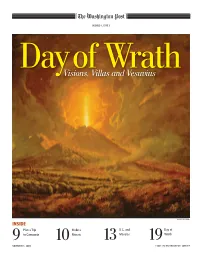

Day of Wrath.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 Day of Wrath Visions, Villas and Vesuvius HUNTINGTON LIBRARY INSIDE Plan a Trip Make a D.C. and Day of 9 to Campania 10 Mosaic 13 Mosaics 19 Wrath NOVEMBER 5, 2008 © 2008 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program About Day of Wrath Lesson: The influence of ancient Greece on A Sunday Style & Arts review of the National Gallery of Art the Roman Empire and Western civilization exhibit, “Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture Around can be seen in its impact on the arts that the Bay of Naples,” and a Travel article, featuring the villas remain in contemporary society. near Vesuvius, are the stimulus for this month’s Post NIE online Level: Low to high guide. This is the first exhibition of Roman antiquities at the Subjects: Social Studies, Art National Gallery. Related Activity: Mathematics, English “The lost-found story of Pompeii, which seemed to have a moral — of confidence destroyed and decadence chastised — appeared ideally devised for the ripe Victorian mind.” But its influence did not stop in 19th-century England. Pompeian influences exist in the Library of Congress, the Senate Appropriations Committee room and around D.C. We provide resources to take a Road Trip (or Metro ride) to some of these places. Although the presence of Vesuvius that destroyed and preserved a way of life is not forgotten, the visitor to the exhibit is taken by the garden of rosemary and laurel, the marble and detailed craftsmanship, the frescos and mosaics. -

Henryk Siemiradzki and the International Artistic Milieu

ACCADEMIA POL ACCA DELLE SCIENZE DELLE SCIENZE POL ACCA ACCADEMIA BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA E CENTRO BIBLIOTECA ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, L’ITALIA E LA RINASCITA E LA RINASCITA L’ITALIA TOMMASINI, FRANCESCO IN ROME DELLA INDIPENDENTE POLONIA A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK CONFERENZE 145 ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA ISSN 0239-8605 ROMA 2020 ISBN 978-83-956575-5-9 CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK. ROMA 2020 Pubblicato da AccademiaPolacca delle Scienze Bibliotecae Centro di Studi aRoma vicolo Doria, 2 (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma tel. +39 066792170 e-mail: [email protected] www.rzym.pan.pl Il convegno ideato dal Polish Institute of World Art Studies (Polski Instytut Studiów nad Sztuką Świata) nell’ambito del programma del Ministero della Scienza e dell’Istruzione Superiore della Repubblica di Polonia (Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education) “Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” (National Programme for the Develop- ment of Humanities) - “Henryk Siemiradzki: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings” (“Tradition 1 a”, no. 0504/ nprh4/h1a/83/2015). Il convegno è stato organizzato con il supporto ed il contributo del National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage POLONIKA (Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kul- turowego za Granicą POLONIKA). Redazione: Maria Nitka, Agnieszka Kluczewska-Wójcik Recensione: Prof. -

Art and Art of Design Учебное Пособие Для Студентов 2-Го Курса Факультета Прикладных Искусств

Министерство образования Российской Федерации Амурский государственный университет Филологический факультет С. И. Милишкевич ART AND ART OF DESIGN Учебное пособие для студентов 2-го курса факультета прикладных искусств. Благовещенск 2002 1 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета филологического факультета Амурского государственного университета Милишкевич С.И. Art and Art of Design. Учебное пособие. Амурский гос. Ун-т, Благовещенск: 2002. Пособие предназначено для практических занятий по английскому языку студентов неязыковых факультетов, изучающих дизайн. Учебные материалы и публицистические статьи подобраны на основе аутентичных источников и освещают последние достижения в области дизайна. Рецензенты: С.В.Андросова, ст. преподаватель кафедры ин. Языков №1 АмГУ; Е.Б.Лебедева, доцент кафедры фнглийской филологии БГПУ, канд. Филологических наук. 2 ART GALLERIES I. Learn the vocabulary: 1) be famous for -быть известным, славиться 2) hordes of pigeons -стаи голубей 3) purchase of -покупка 4) representative -представитель 5) admission -допущение, вход 6) to maintain -поддерживать 7) bequest -дар, наследство 8) celebrity -известность, знаменитость 9) merchant -торговец 10) reign -правление, царствование I. Read and translate the text .Retell the text (use the conversational phrases) LONDON ART GALLERIES On the north side, of Trafalgar Square, famous for its monument to Admiral Nelson ("Nelson's Column"), its fountains and its hordes of pigeons, there stands a long, low building in classic style. This is the National Gallery, which contains Britain's best-known collection of pictures. The collection was begun in 1824, with the purchase of thirty-eight pictures that included Hogarth's satirical "Marriage a la Mode" series, and Titian's "Venus and Adonis". The National Gallery is rich in paintings by Italian masters, such as Raphael, Correggio, and Veronese, and it contains pictures representative of all European schools of art such as works by Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, El Greco, and nineteenth century French masters. -

IFA Alumni Newsletter 2017

Number 52 – Fall 2017 NEWSLETTERAlumni Published by the Alumni Association of Contents From the Director ...............3 The Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Updates ...............20 in the Aftermath of the A Wistful ‘So Long’ to our Beloved May 4, 1970 Kent State Killings ....8 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred and Admired Director Pat Rubin ....4 in 2016-2017 .................30 Thinking out of the Box: You Never From Warburg to Duke: Know Where it Will Lead .........12 Masters Degrees Conferred Living at the Institute ............6 in 2016-2017 .................30 The Year in Pictures ............14 Institute Donors ...............32 Faculty Updates ...............16 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Officers: Advisory Council Members: Committees: President William Ambler Walter S. Cook Lecture Jennifer Eskin [email protected] Jay Levenson, Chair [email protected] Susan Galassi [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President and Kathryn Calley Galitz Jennifer Eskin Acting Treasurer [email protected] Susan Galassi Jennifer Perry Matthew Israel Debra Pincus [email protected] [email protected] Katherine Schwab Lynda Klich Secretary [email protected] Newsletter Johanna Levy Anne Hrychuk Kontokosta Martha Dunkelman [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Debra Pincus Connor Hamm, student assistant [email protected] History of the Institute of Fine Arts Rebecca Rushfield, Chair [email protected] Alumni Reunion Alicia Lubowski-Jahn, Chair [email protected] William Ambler 2 From the Director Christine Poggi, Judy and Michael Steinhardt Director Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick varied program. It will include occasional Collection, Museum of Modern Art, and a collaboration and co-sponsorship of exhibitions, diverse range of other museums. -

Myths of Pompeii: Reality and Legacy

Anne Lill Myths of Pompeii: reality and legacy The aim of the article is to examine some aspects of the meaning of Pompeii over time, as a cultural phenomenon in European tradition. The objective and subjective truths of Pompeii do not always coincide, and the analysis of mythical archetypes helps to cast light on these re- lationships. Tackling wall-paintings as narratives and in contextual connection with the surroundings helps to emphasise mythical arche- types in their mutual relationships: life and death, joy and suffering, and man and woman. The study of antiquity makes it possible to delve into the different manifestations of human nature, into the functioning of various cul- tural forms in society, expressions of religion and rational principles. It is not often that this can be done in such a complex form as in the case of Pompeii. Pompeii as a cultural phenomenon unites key issues from different fields: linguistics and philology, religion and ethics, natural sci- ences, philosophy and art. All of these together reveal different aspects of the history of ideas and traditions and their impact on later eras. The latter aspect in particular makes everything related to Pompeii signifi- cant and alive. It is strange how this relatively insignificant provincial town in Ancient Roman culture became so influential later, especially in the 19th century European intellectual life. In literature and art we do not encounter Pompeii itself, but rath- er a mythologised image of that town. If we understand myth to be a world-view resting on tradition, which shapes and influences people’s behaviour and ways of thinking, and is expressed in various forms of 140 Anne Lill Fig. -

Volcanoes, Disaster, and Evil in Victory

Volcanoes, Disaster, and Evil in Victory Richard Niland University of Strathclyde, Glasgow In Evil in Modern Thought (2002) Susan Neiman treats the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 as an important moment in the evolution of reflection on the subject of evil, noting that the event instigated a divergent “shift in consciousness” in which “natural evils no longer have any seemly relation to moral evils” (2004: 250). Treating the theodicy of Leibniz and the responses of Rousseau and Voltaire to the disaster, Neiman notes that “After Lisbon, the word evil was restricted to what was once called moral evil” (268). In this reading of modernity, Lisbon, and later Auschwitz, “stand for symbols of the breakdown of the worldviews of their era” (8), with the former the last instance in philosophical tradition where natural disaster is interpreted in the context of evil, and the latter confirming that the origins of evil must be searched for in the earthly and human. While Conrad’s life and writing do not typically summon the spectre of theological rumination, they are nevertheless, by now, firmly associated with specific historical instances of evil in modernity, or, perhaps more accurately, the evils of modernity. “Heart of Darkness,” inspired by Conrad’s travels to the Belgian Congo of King Leopold II, exposes the atrocities of a particular phase of extractive nineteenth-century imperial exploitation, with the experience offering Marlow a passing glimpse of “something great and invincible, like evil or truth” (55). Nostromo, occupied with the process and consequences of the “conquest of the earth” in the context of modernity, capitalism, state formation and mining in Latin America, also scrutinizes the “spirits of good and evil that hover near every concealed treasure of the earth” (501). -

The Russian Sale Wednesday 26 November 2014

the russian sale Wednesday 26 November 2014 The Russian sale Wednesday 26 November 2014 at 14.00 101 New Bond Street, London Bonhams Please see BaCk enquiRies illustraTions 101 New Bond Street of CaTalogue foR london Front cover: lot 30 London W1S 1SR imPortanT noTiCe Daria Chernenko Back cover: lot 145 To BiddeRs +44 (0) 20 7468 8338 Inside front: lot 23 www.bonhams.com [email protected] Inside back: lot 41(detail) Bids Opposite page: lot 11 Viewing +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Cynthia Coleman Sparke london +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8357 TO Submit A claim for Saturday 22 November To bid via the internet please [email protected] ReFund of VAT, HMRC 11.00 to 15.00 visit www.bonhams.com Require lots to Be Sunday 23 November Ksenija Krapivina exporteD from the EU 11.00 to 15.00 Please provide details of the lots +44 (0) 207 468 8312 within strict DeadlineS. Monday 24 November on which you wish to place bids [email protected] For lots on which Import 9.00 to 16.30 at least 24 hours prior to the VAT has BeeN chargeD Tuesday 25 November sale. Maryna Nekliudova (markeD in the catalogue 9.00 to 16.30 +44 (0) 207 468 8312 with A *) lots Must Be Wednesday 26 November New bidders must also provide [email protected] exporteD within 30 days 9.00 to 11.00 proof of identity when submitting of Bonhams’ ReCeipt of bids. Failure to do this may Jonathan Horwich payment and within 3 CusTomeR serviCes result Global Director, Picture Sales months of the sale date. -

Neoclassical Reverberations of Antiquity (Torino, 6-9 Oct 14)

Neoclassical Reverberations of Antiquity (Torino, 6-9 Oct 14) Archivio di Stato, Piazzetta Mollino, 1, 10124 Torino, 06.–09.10.2014 Daniela Castaldo, Università del Salento- Dip. Beni Cuturali NEOCLASSICAL REVERBERATIONS OF DISCOVERING ANTIQUITY Twelfth Conference of the ICTM Study Group for the Iconography of the Performing Arts, Istituto per i Beni Musicali in Piemonte Programme Monday, 6 October 9.30 -10.00 Registration 10.00-10.30 Greetings – Opening Frame session–Chair: CRISTINA SANTARELLI (Istituto per i Beni Musicali in Piemonte, Torino) 10.30-11.00 CHRISTIAN GRECO (Museo Egizio, Torino), The Role played by Turin in the field of Aegyptological research 11.00-11.30 ZDRAVKO BLAŽEKOVI (Research Center for Music Iconography, The Graduate Center, CUNY), Ancient Organology Before and After Herculaneum 11.00-11.30 Coffee break 12.00-12.30 PAOLA D’ALCONZO (Università “Federico II”, Napoli), Facing Antiquity Departure and Return: Naples in the Eighteenth Century 12.30-13.00 MICHELA COSTANTINI (Torino), Common Antiquarian Interests Found in the Epistolary Exchanges between the Architect and Piedmontese Erudite Francesco Ottavio Magnocavalli and Members of the Roman Arcadia in the Middle of the Eighteenth Century: The Case of the Ancient Theater of Herculaneum First session: Neoclassicism in European Painting, Sculpture and Applied Arts (Part One) Chair: NICOLETTA GUIDOBALDI (Università di Bologna, Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Ravenna) 15.00-15.30 JORDI BALLESTER GIBERT (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), Music and Poetics of Ancient -

Turgenev and the Question of the Russian Artist

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, SIDNEY SUSSEX COLLEGE TURGENEV AND THE QUESTION OF THE RUSSIAN ARTIST Luis Sundkvist Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 Under the supervision of Dr Diane Oenning Thompson Luis Sundkvist “Turgenev and the Question of the Russian Artist” Summary: This thesis is concerned with the thoughts of the Russian writer Ivan Turgenev (1818-83) on the development of the arts in his native country and the specific problems facing the Russian artist. It starts by considering the state of the creative arts in Russia in the early nineteenth century and suggests why even towards the end of his life Turgenev still had some misgivings as to whether painting and music had become a real necessity for Russian society in the same way that literature clearly had. A re-appraisal of On the Eve (1860) then follows, indicating how the young sculptor Shubin in this novel acts as the author’s alter ego in a number of respects, in particular by reflecting Turgenev’s views on heroism and tragedy. The change in Shubin’s attitude towards Insarov, whom the sculptor at first tries to belittle before eventually comparing him to the noble Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, can be said to anticipate Turgenev’s own feelings about Bazarov in Fathers and Children (1862) and the way that this ‘nihilist’ attained the stature of a true tragic hero. In this chapter, too, the clichéd notion of Turgenev’s alleged affinity with Schopenhauer is firmly challenged—an issue that is taken up again later on in the discussion of Phantoms (1864) and Enough! (1865). -

Romanticism.Pdf

Romanticism 1 Romanticism Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818 Eugène Delacroix, Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, taking its Orientalist subject from a play by Lord Byron Romanticism 2 Philipp Otto Runge, The Morning, 1808 Romanticism (also the Romantic era or the Romantic period) was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. Partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution,[1] it was also a revolt against aristocratic social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature.[] It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography,[2] education[3] and the natural sciences.[4] Its effect on politics was considerable and complex; while for much of the peak Romantic period it was associated with liberalism and radicalism, in the long term its effect on the growth of nationalism was probably more significant. The movement validated strong emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as apprehension, horror and terror, and awe—especially that which is experienced in confronting the sublimity of untamed nature and its picturesque qualities, both new aesthetic categories. It elevated folk art and ancient custom to something noble, made spontaneity a desirable characteristic (as in the musical impromptu), and argued for a "natural" epistemology of human activities as conditioned by nature in the form of language and customary usage. -

Pompeii in Literature

DAAD Summer School “Dialogue on Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis” POMPEII IN LITERATURE Director Student Erwin Emmerling Ileana Makaridou Organizing Committee Dr. Roberta Fonti Dr. Sara Saba Dr. Anna Anguissola ABSTRACT Pompeii was a large Roman town in the Italian region of Campania which was completely buried in volcanic ash following the eruption of nearby Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE. The town was excavated in the 19th and 20th century CE and due to its excellent state of preservation it has given an invaluable insight into the Roman world and may lay claim to being the richest archaeological site in the world in terms of the sheer volume of data available to scholars. It is one of the most significant proofs of Roman civilization and, like an open book, provides outstanding information on the art, customs, trades and everyday life of the past. Keywords: (max 5) ABOUT THE AUTHOR My name is Iliana Makaridou , 23 years old, born on January 21,1993.I’ve been living in Komotini all my life. Traveling is one of my hobbies. I am currently studying at Department of Language, Literature and Culture of the Black Sea Countries-Democritus University of Thrace. I would like to travel all over the world. I’m a nice fun and friendly person, I’m trying my best to be punctual. I have a creative mind and am always up for new challenges. Ileana, Makaridou 1. INTRODUCTION Today, archaeologists, architects and even artists are being inspired by ancient Rome anew. The ancient Roman city of Pompeii has been frequently featured in literature and popular culture since its modern rediscovery. -

Nana by Marcel Suchorowsky: the History of Russian Empire's Most

UDC 7.07:330.1]:947.7-25“18/20” DOI: 10.18523/2617-8907.2019.2.98-104 Nadiia Pavlichenko NANA BY MARCEL SUCHOROWSKY: THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN EMPIRE’S MOST EXPENSIVE PAINTING The article describes the story of painting Nana (1881) by Marcel Suchorowsky known as the most expensive painting sold by a painter in the Russian Empire. But the art piece differs a lot from the general line of the local art market situation, which was defined by special institutions, such as the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. The main aspects are taken into consideration, such as: critical analysis of the painting, the story of the plot, which refers to Émile Zola’s novel Nana, the painter’s individual and innovative exposition strategy, etc. The history of Nana and its special exhibitions in Europe and the USA through the period of 1981–2012 are described. Reports in the USA periodics serve as a special source of analysis, as long as they allow tracing Nana’s movements and public interest. It was exhibited in the “panorama” style using special lightning and additional objects to imitate the three-dimension space and thus became a popular entertainment. Painting Nana is a very interesting cultural phenomenon as long as it obtained notorious glory due to its provocative plot and an excellent academic technique. It is not only the surprising price, but public reaction that is the most important. Keywords: Marcel Suchorowsky, Nana, relisting painting, panorama exhibition, art market. Art market history proves that each new stunning from the beginning until nowadays and to depict its money record for selling an art piece reveals perception in society.