Turgenev and the Question of the Russian Artist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

К. Ju. Lappo-Danilevskij. Labyrinthe Der Intertextualität (Friedrich

Zeitschrift für Slavische Philologie Band 59 • Heft 2 • 2000 Begründet von M. VASMER Fortgeführt von M. WOLTNER H. BRÄUER Herausgegeben von T. BERGER P. BRANG H. KEIPERT W. KOSCHMAL SONDERDRUCK Universitätsverlag C. WINTER Heidelberg Labyrinthe der Intertextualität (Friedrich Schiller und Vjaceslav Ivanov) Dmytro CyzevsJcyj in memoriam Als F. M. Dostoevskij 1861 in seinem Artikel „Kniznost' i gramot- nost'" konstatierte, daß Schiller den Russen in Fleisch und Blut über- gegangen sei, daß zwei vorangegangene Generationen auf der Grund- lage von Schillers Werken erzogen worden seien,1 hatte Schillers Ein- fluß auf die Russen seinen Höhepunkt erreicht. Die neunbändige Aus- gabe der „Gesammelten Werke" (erstmals: 1857-61), die von N. V. Gerbel' vorbereitet worden war, erlebte in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts sieben Auflagen und spielte eine außerordentliche Rolle bei der Verbreitung der Texte Schillers in Rußland.2 Der deutsche Dichter wurde zum Symbol der schwärmerischen Freiheitsliebe, der Treue zu hohen Idealen, der Vergöttlichung der abstrakten Schönheit etc. Gleichzeitig war Schiller nicht mehr ausschließlich der Gedanken- welt hochgebildeter und empfindsamer Intellektueller vorbehalten, sondern wurde zum festen Bestandteil der Jugenderziehung und -lek- türe. In den Werken Dostoevskijs findet man zunehmend Gestalten rus- sischer Sehillerianer. Dostoevskij stellte die meisten ironisch dar, was nicht bedeutet, daß er selbst eine Abneigung gegen Schiller hatte. Seine Charakteristik Schillers aus dem Jahre 1861 wiederholte Dostoevskij 1876 fast wörtlich in seinem „Tagebuch eines Schriftstel- lers".3 Er verstärkte sie sogar noch, indem er emphatische Ausdrücke benutzte, wie: Schiller habe sich in die russische Seele eingesaugt, er habe auf ihr ein Brandmal hinterlassen; Éukovskijs Übersetzungen hätten dazu einen besonders großen Beitrag geleistet. -

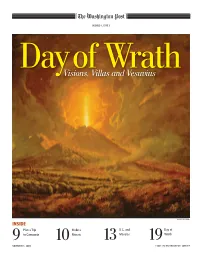

Day of Wrath.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 Day of Wrath Visions, Villas and Vesuvius HUNTINGTON LIBRARY INSIDE Plan a Trip Make a D.C. and Day of 9 to Campania 10 Mosaic 13 Mosaics 19 Wrath NOVEMBER 5, 2008 © 2008 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program About Day of Wrath Lesson: The influence of ancient Greece on A Sunday Style & Arts review of the National Gallery of Art the Roman Empire and Western civilization exhibit, “Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture Around can be seen in its impact on the arts that the Bay of Naples,” and a Travel article, featuring the villas remain in contemporary society. near Vesuvius, are the stimulus for this month’s Post NIE online Level: Low to high guide. This is the first exhibition of Roman antiquities at the Subjects: Social Studies, Art National Gallery. Related Activity: Mathematics, English “The lost-found story of Pompeii, which seemed to have a moral — of confidence destroyed and decadence chastised — appeared ideally devised for the ripe Victorian mind.” But its influence did not stop in 19th-century England. Pompeian influences exist in the Library of Congress, the Senate Appropriations Committee room and around D.C. We provide resources to take a Road Trip (or Metro ride) to some of these places. Although the presence of Vesuvius that destroyed and preserved a way of life is not forgotten, the visitor to the exhibit is taken by the garden of rosemary and laurel, the marble and detailed craftsmanship, the frescos and mosaics. -

2004/1 (7) 1 Art on the Line

Art on the line A Russian kaleidoscope: shifting visions of the emergence and development of art criticism in the electronic archive Russian Visual Arts, 1800–1913 Carol Adlam Department of Russian, School of Modern Languages, University of Exeter, Queen’s Drive, Exeter EX2 4QH, UK [email protected] Alexey Makhrov Department of Russian, School of Modern Languages, University of Exeter, Queen's Drive, Exeter, EX4 4QH, UK and independent researcher, Switzerland [email protected] 1 Origins notes on major art critics of the period under The project Russian Visual Arts, 1800–1913 consideration, new editorial and translators’ as it appears today at the Humanities notes, and a glossary. The project also pro- Research Institute at the University of Sheffield vides details of on-going research activity in (http://hri.shef.ac.uk/rva*) is the result of three the field: these include the work of various years of AHRB-funded labour (2000–2003) by team members in writing articles, delivering a team of individuals from the Universities of papers and also running a commemorative Exeter and Sheffield, the British Library, and conference at the University of Exeter in the National Library of Russia.1 Russian Visual September 2003 (Art Criticism, 1700–1900: Arts, 1800–1913 is a compendious electronic Emergence, Development, Interchange in archive consisting of four sub-archive areas: a Eastern and Western Europe). textbase of approximately 100 primary texts, in There were several sources of inspiration Russian and in many cases in English transla- -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

Henryk Siemiradzki and the International Artistic Milieu

ACCADEMIA POL ACCA DELLE SCIENZE DELLE SCIENZE POL ACCA ACCADEMIA BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA E CENTRO BIBLIOTECA ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, L’ITALIA E LA RINASCITA E LA RINASCITA L’ITALIA TOMMASINI, FRANCESCO IN ROME DELLA INDIPENDENTE POLONIA A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK CONFERENZE 145 ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA ISSN 0239-8605 ROMA 2020 ISBN 978-83-956575-5-9 CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK. ROMA 2020 Pubblicato da AccademiaPolacca delle Scienze Bibliotecae Centro di Studi aRoma vicolo Doria, 2 (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma tel. +39 066792170 e-mail: [email protected] www.rzym.pan.pl Il convegno ideato dal Polish Institute of World Art Studies (Polski Instytut Studiów nad Sztuką Świata) nell’ambito del programma del Ministero della Scienza e dell’Istruzione Superiore della Repubblica di Polonia (Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education) “Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” (National Programme for the Develop- ment of Humanities) - “Henryk Siemiradzki: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings” (“Tradition 1 a”, no. 0504/ nprh4/h1a/83/2015). Il convegno è stato organizzato con il supporto ed il contributo del National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage POLONIKA (Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kul- turowego za Granicą POLONIKA). Redazione: Maria Nitka, Agnieszka Kluczewska-Wójcik Recensione: Prof. -

Marbacher Schiller-Bibliographie 2011

NICOLAI RIEDEL In Zusammenarbeit mit Herman Moens MARBACHER SCHILLER-BIBLIOGRAPHIE 2011 und Nachträge Vorbemerkung Die großen Schiller-Jubiläumsjahre 2005 und 2009 haben ihre langen Schatten vorausgeworfen und eine ungewöhnliche Reichhaltigkeit wissenschaftlicher Ver- öffentlichungen hervorgebracht, sie haben aber auch ein dichtes Netzwerk von Spuren hinterlassen und verzweigte Gleissysteme in die Forschungslandschaften gelegt. Waren in der Bibliographie für das Berichtsjahr 2010 »nur« etwa 460 Titel dokumentiert, was ziemlich genau dem Durchschnitt des vorangegangenen De- zenniums entspricht, so sind es für 2011 genau 801 Nachweise. Diese hohe Zahl mag zunächst Erstaunen hervorrufen, denn es handelt sich um eine Steigerung von rund 43 %. Die statistischen und quantifizierenden Überlegungen, wie sie in den Vorbemerkungen von 2010 formuliert wurden, sollen hier aber nicht weiter- geführt werden, denn es hat sich herausgestellt, dass eine personenbezogene For- schung in den seltensten Fällen messbar und prognostizierbar ist. Die Summe der Nachweise setzt sich im Wesentlichen aus vier Faktoren zusammen, die im Fol- genden knapp umrissen werden sollen: 1. Im Berichtsjahr 2010 wurde absichtlich darauf verzichtet, solche Titel aufzunehmen, die erst nach Redaktionsschluss der Bibliographie verifiziert werden konnten, um Buchstabenzusätze bei den Refe- renznummern zu vermeiden. Auf diese Weise gelangten schon sehr viele Titel aus der Warteschleife in die Basis-Datei für 2011. – 2. Für das Berichtsjahr 2011 ist dieses Prinzip zugunsten eines verbesserten Informationsflusses wieder auf- gegeben worden. Nach Redaktionsschluss wurden noch einmal 26 autopsierte Nachweise in die Systematik integriert. Diese sind nun (aus typographischen Er- wägungen) nicht mehr mit a, b und c gekennzeichnet, sondern mit dezenten hoch- gestellten Ziffern (z. B. 5121, 5122). – 3. Der Redaktionsschluss der Bibliographie wurde um einen Monat nach hinten verschoben, d. -

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco

From Triumphal Gates to Triumphant Rotting: Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie A. Kivelson, Chair Assistant Professor Paolo Asso Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo Assistant Professor Benjamin B. Paloff With much gratitude to Valerie Kivelson, for her unflagging support, to Yana, for her coffee and tangerines, and to the Prawns, for keeping me sane. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter I. Writing Empire: Lomonosov’s Rivalry with Imperial Rome ................................... 31 II. Qualifying Empire: Morals and Ethics of Derzhavin’s Romans ............................... 76 III. Freedom, Tyrannicide, and Roman Heroes in the Works of Pushkin and Ryleev .. 122 IV. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov and the Rejection of the Political [Rome] .................. 175 V. Blok, Catiline, and the Decomposition of Empire .................................................. 222 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 271 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

What Is to Be Done? Discussions in Russian Art Theory and Criticism I

WHAT IS TO BE DONE? DISCUSSIONS IN RUSSIAN ART THEORY AND CRITICISM I 6th Graduate Workshop of the RUSSIAN ART & CULTURE GROUP September 20th, 2018 | Jacobs University Bremen Cover: Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Manuscript of his novel “Что делать?” [What Is to be Done?] (detail), 1863; and Ivan Kramskoi, Христос в пустыне [Christ in the Desert] (detail), 1872, Tretyakov Gallery Moscow. WHAT IS TO BE DONE? DISCUSSIONS IN RUSSIAN ART THEORY AND CRITICISM I The sixth graduate workshop of the Russian Art & Culture Group will focus on main tendencies in Russian art theory of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Therefore, responses to the question What Is to Be Done? (Что делать?) in academic circles as well as by art critics, writers, impresarios, and other members of the Russian intelligentsia shall be explored. 2 | PROGRAM 6th Graduate Workshop of the Russian Art & Culture Group Jacobs University Bremen, Campus Ring 1, 28759 Bremen, Lab 3. PROGRAM THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 20TH 10.30 Opening: Welcome Address Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche, Jacobs University Bremen Panel I: The Academy and Its Opponents Chair: Tanja Malycheva 11.00 Russian Pensionnaires of the Imperial Academy of Arts in Venice in the Second Half of the 18th Century Iana Sokolova, University of Padua 11.30 Escape from the Academy: Why Russian Artists Left St. Petersburg and Moved to Munich at the End of the 19th Century Nadezhda Voronina, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich 12.00 A Critic’s Tale by Vladimir Stasov Ludmila Piters-Hofmann, Jacobs University Bremen 12.30 Lunch Break (not included) Panel II: New Approaches and Aesthetic Norms Chair: Ludmila Piters-Hofmann 14.00 The Discussion of the Protection of the Russian Cultural Heritage in Russian Art Journals at the End of the 19th / Beginning of the 20th Century Anna Kharkina, Södertörn University 14.30 Pre-Raphaelites and Peredvizhniki: Pathosformel and Prefiguration in the 20th Century Marina Toropygina, Russian State Institute for Cinematography (VGIK) PROGRAM |3 15.00 “Colors, Colors .. -

Russian Military Developments and Strategic Implications

i [H.A.S.C. No. 113–105] RUSSIAN MILITARY DEVELOPMENTS AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD APRIL 8, 2014 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–450 WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, http://bookstore.gpo.gov. For more information, contact the GPO Customer Contact Center, U.S. Government Printing Office. Phone 202–512–1800, or 866–512–1800 (toll-free). E-mail, [email protected]. COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California, Chairman MAC THORNBERRY, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina LORETTA SANCHEZ, California J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina JEFF MILLER, Florida ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania JOE WILSON, South Carolina SUSAN A. DAVIS, California FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island ROB BISHOP, Utah RICK LARSEN, Washington MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio JIM COOPER, Tennessee JOHN KLINE, Minnesota MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JOE COURTNEY, Connecticut TRENT FRANKS, Arizona DAVID LOEBSACK, Iowa BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas JOHN GARAMENDI, California DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia ROBERT J. WITTMAN, Virginia COLLEEN W. HANABUSA, Hawaii DUNCAN HUNTER, California JACKIE SPEIER, California JOHN FLEMING, Louisiana RON BARBER, Arizona MIKE COFFMAN, Colorado ANDRE´ CARSON, Indiana E. SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia CAROL SHEA-PORTER, New Hampshire CHRISTOPHER P. GIBSON, New York DANIEL B. MAFFEI, New York VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri DEREK KILMER, Washington JOSEPH J. HECK, Nevada JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JON RUNYAN, New Jersey TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia SCOTT H. -

US Sanctions on Russia

U.S. Sanctions on Russia Updated January 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45415 SUMMARY R45415 U.S. Sanctions on Russia January 17, 2020 Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian Specialist in European aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russia in Affairs response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Most Members of Congress support a robust Kristin Archick Specialist in European use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions. Affairs Sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Rebecca M. Nelson Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Specialist in International Ukraine: the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Trade and Finance Ukraine Act of 2014 (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859). Dianne E. Rennack Specialist in Foreign Policy In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Countering Russian Influence Legislation in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L.