The Portrayal of Disaster in Western Fine Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day of Wrath.Indd

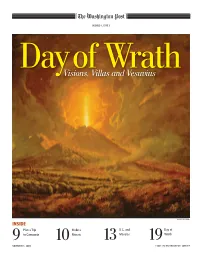

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 Day of Wrath Visions, Villas and Vesuvius HUNTINGTON LIBRARY INSIDE Plan a Trip Make a D.C. and Day of 9 to Campania 10 Mosaic 13 Mosaics 19 Wrath NOVEMBER 5, 2008 © 2008 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program About Day of Wrath Lesson: The influence of ancient Greece on A Sunday Style & Arts review of the National Gallery of Art the Roman Empire and Western civilization exhibit, “Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture Around can be seen in its impact on the arts that the Bay of Naples,” and a Travel article, featuring the villas remain in contemporary society. near Vesuvius, are the stimulus for this month’s Post NIE online Level: Low to high guide. This is the first exhibition of Roman antiquities at the Subjects: Social Studies, Art National Gallery. Related Activity: Mathematics, English “The lost-found story of Pompeii, which seemed to have a moral — of confidence destroyed and decadence chastised — appeared ideally devised for the ripe Victorian mind.” But its influence did not stop in 19th-century England. Pompeian influences exist in the Library of Congress, the Senate Appropriations Committee room and around D.C. We provide resources to take a Road Trip (or Metro ride) to some of these places. Although the presence of Vesuvius that destroyed and preserved a way of life is not forgotten, the visitor to the exhibit is taken by the garden of rosemary and laurel, the marble and detailed craftsmanship, the frescos and mosaics. -

Daxer & Marschall 2015 XXII

Daxer & Marschall 2015 & Daxer Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com XXII _Daxer_2015_softcover.indd 1-5 11/02/15 09:08 Paintings and Oil Sketches _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 1 10/02/15 14:04 2 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 2 10/02/15 14:04 Paintings and Oil Sketches, 1600 - 1920 Recent Acquisitions Catalogue XXII, 2015 Barer Strasse 44 I 80799 Munich I Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 I Fax +49 89 28 17 57 I Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] I www.daxermarschall.com _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 3 10/02/15 14:04 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 4 10/02/15 14:04 This catalogue, Paintings and Oil Sketches, Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings and Oil Sketches erreicht Sie appears in good time for TEFAF, ‘The pünktlich zur TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht. TEFAF 12. - 22. März 2015, dem Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres. is the international art-market high point of the year. It runs from 12-22 March 2015. Das diesjährige Angebot ist breit gefächert, mit Werken aus dem 17. bis in das frühe 20. Jahrhundert. Der Katalog führt Ihnen The selection of artworks described in this einen Teil unserer Aktivitäten, quasi in einem repräsentativen catalogue is wide-ranging. It showcases many Querschnitt, vor Augen. Wir freuen uns deshalb auf alle Kunst- different schools and periods, and spans a freunde, die neugierig auf mehr sind, und uns im Internet oder lengthy period from the seventeenth century noch besser in der Galerie besuchen – bequem gelegen zwischen to the early years of the twentieth century. -

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions 2013 Kunsthandel Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com My special thanks go to Sabine Ratzenberger, Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald, for their research and their work on the text. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Sandrine Balan, Alexandra Bouillot-Chartier, Corinne Chorier, Sue Cubitt, Roland Dorn, Jürgen Ecker, Jean-Jacques Fernier, Matthias Fischer, Silke Francksen-Mansfeld, Claus Grimm, Jean- François Heim, Sigmar Holsten, Saskia Hüneke, Mathias Ary Jan, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, Michael Koch, Wolfgang Krug, Marit Lange, Thomas le Claire, Angelika and Bruce Livie, Mechthild Lucke, Verena Marschall, Wolfram Morath-Vogel, Claudia Nordhoff, Elisabeth Nüdling, Johan Olssen, Max Pinnau, Herbert Rott, John Schlichte Bergen, Eva Schmidbauer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jesper Svenningsen, Rudolf Theilmann, Wolf Zech. his catalogue, Oil Sketches and Paintings nser diesjähriger Katalog 'Oil Sketches and Paintings 2013' erreicht T2013, will be with you in time for TEFAF, USie pünktlich zur TEFAF, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. 14. - 24. März 2013. TEFAF runs from 14-24 March 2013. Die in dem Katalog veröffentlichten Gemälde geben Ihnen einen The selection of paintings in this catalogue is Einblick in das aktuelle Angebot der Galerie. Ohne ein reiches Netzwerk an designed to provide insights into the current Beziehungen zu Sammlern, Wissenschaftlern, Museen, Kollegen, Käufern und focus of the gallery’s activities. -

Henryk Siemiradzki and the International Artistic Milieu

ACCADEMIA POL ACCA DELLE SCIENZE DELLE SCIENZE POL ACCA ACCADEMIA BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA E CENTRO BIBLIOTECA ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, L’ITALIA E LA RINASCITA E LA RINASCITA L’ITALIA TOMMASINI, FRANCESCO IN ROME DELLA INDIPENDENTE POLONIA A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK CONFERENZE 145 ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA ISSN 0239-8605 ROMA 2020 ISBN 978-83-956575-5-9 CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK. ROMA 2020 Pubblicato da AccademiaPolacca delle Scienze Bibliotecae Centro di Studi aRoma vicolo Doria, 2 (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma tel. +39 066792170 e-mail: [email protected] www.rzym.pan.pl Il convegno ideato dal Polish Institute of World Art Studies (Polski Instytut Studiów nad Sztuką Świata) nell’ambito del programma del Ministero della Scienza e dell’Istruzione Superiore della Repubblica di Polonia (Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education) “Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” (National Programme for the Develop- ment of Humanities) - “Henryk Siemiradzki: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings” (“Tradition 1 a”, no. 0504/ nprh4/h1a/83/2015). Il convegno è stato organizzato con il supporto ed il contributo del National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage POLONIKA (Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kul- turowego za Granicą POLONIKA). Redazione: Maria Nitka, Agnieszka Kluczewska-Wójcik Recensione: Prof. -

Art and Art of Design Учебное Пособие Для Студентов 2-Го Курса Факультета Прикладных Искусств

Министерство образования Российской Федерации Амурский государственный университет Филологический факультет С. И. Милишкевич ART AND ART OF DESIGN Учебное пособие для студентов 2-го курса факультета прикладных искусств. Благовещенск 2002 1 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета филологического факультета Амурского государственного университета Милишкевич С.И. Art and Art of Design. Учебное пособие. Амурский гос. Ун-т, Благовещенск: 2002. Пособие предназначено для практических занятий по английскому языку студентов неязыковых факультетов, изучающих дизайн. Учебные материалы и публицистические статьи подобраны на основе аутентичных источников и освещают последние достижения в области дизайна. Рецензенты: С.В.Андросова, ст. преподаватель кафедры ин. Языков №1 АмГУ; Е.Б.Лебедева, доцент кафедры фнглийской филологии БГПУ, канд. Филологических наук. 2 ART GALLERIES I. Learn the vocabulary: 1) be famous for -быть известным, славиться 2) hordes of pigeons -стаи голубей 3) purchase of -покупка 4) representative -представитель 5) admission -допущение, вход 6) to maintain -поддерживать 7) bequest -дар, наследство 8) celebrity -известность, знаменитость 9) merchant -торговец 10) reign -правление, царствование I. Read and translate the text .Retell the text (use the conversational phrases) LONDON ART GALLERIES On the north side, of Trafalgar Square, famous for its monument to Admiral Nelson ("Nelson's Column"), its fountains and its hordes of pigeons, there stands a long, low building in classic style. This is the National Gallery, which contains Britain's best-known collection of pictures. The collection was begun in 1824, with the purchase of thirty-eight pictures that included Hogarth's satirical "Marriage a la Mode" series, and Titian's "Venus and Adonis". The National Gallery is rich in paintings by Italian masters, such as Raphael, Correggio, and Veronese, and it contains pictures representative of all European schools of art such as works by Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, El Greco, and nineteenth century French masters. -

IFA Alumni Newsletter 2017

Number 52 – Fall 2017 NEWSLETTERAlumni Published by the Alumni Association of Contents From the Director ...............3 The Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Updates ...............20 in the Aftermath of the A Wistful ‘So Long’ to our Beloved May 4, 1970 Kent State Killings ....8 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred and Admired Director Pat Rubin ....4 in 2016-2017 .................30 Thinking out of the Box: You Never From Warburg to Duke: Know Where it Will Lead .........12 Masters Degrees Conferred Living at the Institute ............6 in 2016-2017 .................30 The Year in Pictures ............14 Institute Donors ...............32 Faculty Updates ...............16 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Officers: Advisory Council Members: Committees: President William Ambler Walter S. Cook Lecture Jennifer Eskin [email protected] Jay Levenson, Chair [email protected] Susan Galassi [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President and Kathryn Calley Galitz Jennifer Eskin Acting Treasurer [email protected] Susan Galassi Jennifer Perry Matthew Israel Debra Pincus [email protected] [email protected] Katherine Schwab Lynda Klich Secretary [email protected] Newsletter Johanna Levy Anne Hrychuk Kontokosta Martha Dunkelman [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Debra Pincus Connor Hamm, student assistant [email protected] History of the Institute of Fine Arts Rebecca Rushfield, Chair [email protected] Alumni Reunion Alicia Lubowski-Jahn, Chair [email protected] William Ambler 2 From the Director Christine Poggi, Judy and Michael Steinhardt Director Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick varied program. It will include occasional Collection, Museum of Modern Art, and a collaboration and co-sponsorship of exhibitions, diverse range of other museums. -

Kat. Lithographie 30.#1BF1E.Qxd

. r J r e d i e n h c S . P . J www.j-p-schneider.com Herausgeber: J. P. Schneider jr. Kunsthandlung Katalogbeiträge: Max Andreas (MA) Dr. Eva Habermehl (EH) Dr. Roland Dorn (RD) Fotografie: Marthe Andreas Im Trutz Frankfurt 2 Layout und Reproduktion: D-60322 Frankfurt am Main Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg Termin nach Vereinbarung Druck: Grafisches Centrum Cuno GmbH & Co. KG, Calbe +49 (0)69 281033 [email protected] www.j-p-schneider.com © J. P. Schneider jr. Verlag 2018 ISBN 978-3-9802873-5-7 Preise auf Anfrage INHALT Vorwort ......................................................................................... 7 9 Simon-Joseph-Alexandre-Clément Denis Blick auf die Sabiner Berge .............................................. 26 10 Théodore Étienne Pierre Rousseau 1 Johann Wilhelm Schirmer Künstler, skizzierend im Forst von Fontainebleau ...... 28 Badende in italienischer Landschaft ................................ 9 11 Wilhelm Trübner 2 Eduard Wilhelm Pose Selbstbildnis nach rechts, 1876 ......................................... 31 Italienische Landschaft ..................................................... 12 3 Carl Maria Nicolaus Hummel 12 Wilhelm Trübner Italienische Landschaft Wildenten ............................................................................. 35 (Blick von den Albaner Bergen über Nemisee 13 Carl Schuch und Campagna zum Meer) .............................................. 14 Stillleben mit Lauch, Zwiebeln und Käse ..................... 39 4 Carl Morgenstern 14 Otto Scholderer Cadenabbia am Comer -

Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2001 Volume II: Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects Reading the Landscape: Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E. Church Curriculum Unit 01.02.01 by Stephen P. Broker Introduction This curriculum unit uses nineteenth century American landscape paintings to teach high school students about topics in geography, geology, ecology, and environmental science. The unit blends subject matter from art and science, two strongly interconnected and fully complementary disciplines, to enhance learning about the natural world and the interaction of humans in natural systems. It is for use in The Dynamic Earth (An Introduction to Physical and Historical Geology), Environmental Science, and Advanced Placement Environmental Science, courses I teach currently at Wilbur Cross High School. Each of these courses is an upper level (Level 1 or Level 2) science elective, taken by high school juniors and seniors. Because of heavy emphasis on outdoor field and laboratory activities, each course is limited in enrollment to eighteen students. The unit has been developed through my participation in the 2001 Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute seminar, "Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects," seminar leader Jules D. Prown (Yale University, Professor of the History of Art, Emeritus). The "objects" I use in developing unit activities include posters or slides of studio landscape paintings produced by Frederic Church (1826-1900), America's preeminent landscape painter of the nineteenth century, completed during his highly productive years of the 1840s through the 1860s. Three of Church's oil paintings referred to may also be viewed in nearby Connecticut or New York City art museums. -

The Patronage and Collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III During the Era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Victoria Albert &Art & Love The patronage and collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III during the era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert Emmanuel Starcky Essays from a study day held at the National Gallery, London on 5 and 6 June 2010 Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love The patronage and collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III during the era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert Emmanuel Starcky Fig. 1 Workshop of Franz Winterhalter, Portrait of Louis-Philippe (1773–1850), 1840 Oil on canvas, 233 x 167cm Compiègne, Musée national du palais Fig. 2 After Franz Winterhalter, Portrait of Napoleon III (1808–1873), 1860 Tapestry from the Gobelin manufactory, 241 x 159cm Compiègne, Musée national du palais The reputation of certain monarchs is so distorted by caricaturists as to undermine their real achievements. Such was the case with Louis-Philippe (1773–1850; fig. 1), son of Philippe Egalité, who had voted for the execution of his cousin Louis XVI, and with his successor, Napoléon III (1808–73; fig. -

Charity Art Auction in Favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg in Cooperation with the Rotary Clubs Wien-West, Vienna-International, Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten

Rotary Club Wien-West, Vienna-International, Our Auction Charity art Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten in cooperation with That‘s how it‘s done: Due to auction 1. Register: the current, Corona- related situation, BenefizAuktion in favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg restrictions and changes 22. February 2021 Go to www.cs.at/ charityauction and register there; may occur at any time. please register up to 24 hours before the start of the auction. Tell us the All new Information at numbers of the works for which you want to bid. www.cs.at/kunstauktion Alternatively, send us the buying order on page 128. 2. Bidding: Bidding live by phone: We will call you shortly before your lots are called up in the auction. You can bid live and directly as if you were there. Live via WhatsApp: When registering, mark with a cross that you want to use this option and enter your mobile number. You‘re in. We‘ll get in touch with you just before the auction. Written bid: Simply enter your maximum bid in the form for the works of art that you want to increase. This means that you can already bid up to this amount, but of course you can also get the bid for a lower value. Just fill out the form. L ive stream: at www.cs.at/kunstauktion you will find the link for the auction, which will broadcast it directly to your home. 3. Payment: You were able to purchase your work of art, we congratulate you very much and wish you a lot of pleasure with it. -

Jean-François Heim and Marcus Marschall Have Pleasure in Inviting You to the Private View of Their Exhibition Un Désir D'ita

Jean-François Heim and Marcus Marschall Jean-François Heim und Marcus Marschall freuen sich, have pleasure in inviting you Sie anlässlich der gemeinsamen Ausstellung to the private view of their exhibition Un désir d’Italie Un désir d’Italie at Galerie Jean-François Heim, Paris in der Galerie Jean-François Heim in Paris zu empfangen. on Wednesday, 3 June at 5pm Vernissage am Mittwoch, den 3. Juni 2009 ab 17 Uhr, in the frame of Nocturne Rive Droite, www.art-rivedroite.com im Rahmen der Nocturne Rive Droite, www.art-rivedroite.com The exhibition runs from 4 June to 3 July 2009 Die Ausstellung läuft von 4. Juni - 3. Juli 2009, Monday to Friday, 10am - 1pm and 2 - 6pm, and by appointment Montag bis Freitag 10 - 13 und 14 - 18 Uhr, und nach Vereinbarung Galerie Jean-François Heim Galerie Jean-François Heim 134, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré · F-75008 Paris 134, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré · F - 75008 Paris Tel. + 33 (0)1 53 75 06 46 · [email protected] Tel. +33 (0) 1 53 75 06 46 · [email protected] Works can be viewed on our website: www.daxermarschall.com Besuchen Sie vorab auch unsere homepage www.daxermarschall.com Oswald Achenbach (1827 - Düsseldorf - 1905) The Moonlit Bay of Naples with Mount Vesuvius in the Background , 1886 Oil on paper, mounted on panel signed and dated lower right OA 1886 24 x 31.7 cm Literature: Potthoff, Mechthild, Oswald Achenbach. Sein künstlerisches Wirken zur Hochzeit des Bürgertums. Studien zu Leben und Werk, Cologne-Berlin 1995; Sitt, Martina, Ed., Andreas und Oswald Achenbach, das ‚A’ und ‚O’ der Landschaft, exhib. -

Myths of Pompeii: Reality and Legacy

Anne Lill Myths of Pompeii: reality and legacy The aim of the article is to examine some aspects of the meaning of Pompeii over time, as a cultural phenomenon in European tradition. The objective and subjective truths of Pompeii do not always coincide, and the analysis of mythical archetypes helps to cast light on these re- lationships. Tackling wall-paintings as narratives and in contextual connection with the surroundings helps to emphasise mythical arche- types in their mutual relationships: life and death, joy and suffering, and man and woman. The study of antiquity makes it possible to delve into the different manifestations of human nature, into the functioning of various cul- tural forms in society, expressions of religion and rational principles. It is not often that this can be done in such a complex form as in the case of Pompeii. Pompeii as a cultural phenomenon unites key issues from different fields: linguistics and philology, religion and ethics, natural sci- ences, philosophy and art. All of these together reveal different aspects of the history of ideas and traditions and their impact on later eras. The latter aspect in particular makes everything related to Pompeii signifi- cant and alive. It is strange how this relatively insignificant provincial town in Ancient Roman culture became so influential later, especially in the 19th century European intellectual life. In literature and art we do not encounter Pompeii itself, but rath- er a mythologised image of that town. If we understand myth to be a world-view resting on tradition, which shapes and influences people’s behaviour and ways of thinking, and is expressed in various forms of 140 Anne Lill Fig.