Armageddon Averted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ambivalence of Social Change. Triumph Or Trauma

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sztompka, Piotr Working Paper The ambivalence of social change: Triumph or trauma? WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 00-001 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Sztompka, Piotr (2000) : The ambivalence of social change: Triumph or trauma?, WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 00-001, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/50259 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu P 00 - 001 The Ambivalence of Social Change Triumph or Trauma? Piotr Sztompka Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung gGmbH (WZB) Reichpietschufer 50, D-10785 Berlin Dr. Piotr Sztompka is a professor of sociology at the Jagiellonian University at Krakow (Poland), where he is heading the Chair of Theoretical Sociology, as well as the Center for Analysis of Social Change "Europe '89". -

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup the Suppressed Transcripts

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup The Suppressed Transcripts: Part 3 Hearings "About the Illegal Financia) Activity of the CPSU" Editor 's Introduction At the birth of the independent Russian Federation, the country's most pro-Western reformers looked to the West to help fund economic reforms and social safety nets for those most vulnerable to the change. However, unlike the nomenklatura and party bureaucrats who remained positioned to administer huge aid infusions, these reformers were skeptical about multibillion-dollar Western loans and credits. Instead, they wanted the West to help them with a different source of money: the gold, platinum, diamonds, and billions of dollars in hard currency the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and KGB intelligence service laundered abroad in the last years of perestroika. Paradoxically, Western governments generously supplied the loans and credits, but did next to nothing to support the small band of reformers who sought the return of fortunes-estimated in the tens of billions of dollars- stolen by the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, as some in the West have chronicled, the nomenklatura and other functionaries who remained in positions of power used the massive infusion of Western aid to enrich themselves-and impoverish the nation-further. In late 1995, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development concluded that Russian officials had stolen $45 billion in Western aid and deposited the money abroad. Radical reformers in the Russian Federation Supreme Soviet, the parliament that served until its building was destroyed on President Boris Yeltsin's orders in October 1993, were aware of this mass theft from the beginning and conducted their own investigation as part of the only public probe into the causes and circumstances of the 1991 coup attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. -

Access to Resources and Predictability in Armed Rebellion: the FAPC’S Short-Lived “Monaco” in Eastern Congo Kristof Titeca

● ● ● ● Africa Spectrum 2/2011: 43-70 Access to Resources and Predictability in Armed Rebellion: The FAPC’s Short-lived “Monaco” in Eastern Congo Kristof Titeca Abstract: This article discusses the impact of economic resources on the behaviour of an armed group. The availability of resources, and the presence of “lootable” resources in particular, is presumed to have a negative impact on the way an armed group behaves toward the civilian population. The case of the Armed Forces of the Congolese People (Forces Armées du Peuple Congolais, FAPC) in eastern Congo strongly suggests that it is necessary to look beyond this monocausal argument so as to witness the range of other factors at work. In this vein, first, the article demonstrates how the political economy literature underestimates the ease of accessibility of lootable resources. The paper then shows how the behaviour of this armed group was tied to a particular economic interest: In order to access these lootable goods, the FAPC was dependent on pre-established trading networks, so it had to increase the predictability of economic interactions through the construction of a minimum of social and economic order. Second, the article reveals how the political economy literature can underestimate the specific conflict dynamics. Military security in particular has a strong impact in this context. Manuscript received 3 August 2011; accepted 11 October 2011 Keywords: Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda, armed con- flicts, armed forces/military units, informal cross-border trade Kristof Titeca is a postdoctoral fellow from the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), based at the Institute of Development Policy and Man- agement, University of Antwerp. -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission BATTLE- TESTED STRATEGIES TO PREPARE YOUR LIFE AND SOUL FOR THE END TIMES COL. DAVID J. GIAMMONA AND TROY ANDERSON G The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission _Giammona_MilitaryGuide_ET_bb.indd 3 10/1/20 8:02 AM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2021 by David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— for example, electronic, photocopy, recording— without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Giammona, David J., author. | Anderson, Troy (Journalist), author. Title: The military guide to Armageddon: battle-tested strategies to prepare your life and soul for the end times / Col. David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson. Description: Minneapolis, Minnesota: Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020038021 | ISBN 9780800761943 (paperback) | ISBN 9780800762261 (casebound) | ISBN 9781493430086 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spiritual warfare. | End of the world. | Armageddon. Classification: LCC BV4509.5 .G466 2021 | DDC 236/.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038021 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. -

The Blind Leading the Blind

WORKING PAPER #60 The Blind Leading the Blind: Soviet Advisors, Counter-Insurgency and Nation-Building in Afghanistan By Artemy Kalinovsky, January 2010 COLD War INTernaTionaL HISTorY ProjecT Working Paper No. 60 The Blind Leading the Blind: Soviet Advisors, Counter-Insurgency and Nation-Building in Afghanistan By Artemy Kalinovsky THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Mircea Munteanu Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11

God's Master Plan In Prophecy Lesson 13 – The Battle of Armageddon & 2nd Coming of Jesus Christ Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11 Zechariah 12-14 Introduction Rev 19:1 After these things I heard something like a loud voice of a great multitude in heaven, saying, "Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God; While the Wrath of God is being poured out, there was the voice of "a great multitude in heaven" praising God! This is the redeemed church which has missed the Wrath of God and was taken out of Great Tribulation. While the earth is experiencing the judgment of God without mercy, we are experiencing His goodness without judgment! Rev 19:2-3 BECAUSE HIS JUDGMENTS ARE TRUE AND RIGHTEOUS; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and HE HAS AVENGED THE BLOOD OF HIS BOND-SERVANTS ON HER." 3 And a second time they said, "Hallelujah! HER SMOKE RISES UP FOREVER AND EVER." From what is being said in these verse, it is obvious that the church will be fully aware of what is happening upon the earth during this time, yet because we are no longer viewing earth's events through the eyes of mortal flesh, we will understand that God is righteous and true in His judgments. To modern minds it may seem strange to worship and say, “hallelujah” over the fact that God is pouring out judgment, but that is because we see imperfectly now. -

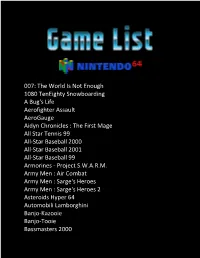

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Leverage and Asset Bubbles: Averting Armageddon with Chapter 11?*

The Economic Journal, 120 (May), 500–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02357.x. Ó The Author(s). Journal compilation Ó Royal Economic Society 2010. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. LEVERAGE AND ASSET BUBBLES: AVERTING ARMAGEDDON WITH CHAPTER 11?* Marcus Miller and Joseph Stiglitz An iconic model with high leverage and overvalued collateral assets is used to illustrate the ampli- fication mechanism driving asset prices to ÔovershootÕ equilibrium when an asset bubble bursts – threatening widespread insolvency and what Richard Koo calls a Ôbalance sheet recessionÕ. Besides interest rates cuts, asset purchases and capital restructuring are key to crisis resolution. The usual bankruptcy procedures for doing this fail to internalise the price effects of asset Ôfire-salesÕ to pay down debts, however. We discuss how official intervention in the form of ÔsuperÕ Chapter 11 actions can help prevent asset price correction causing widespread economic disruption. There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Hamlet From 2007 to 2009 a chain of events, beginning with unexpected losses in the US sub-prime mortgage market, was destined to bring the global financial system close to collapse and to drag the world economy into recession. ÔOne of the key challenges posed by this crisisÕ, says Williamson (2009), Ôis to understand how such major consequences can flow from such a seemingly minor eventÕ. Before describing an amplification mechanism involving overpriced assets and excessive leverage, we begin by looking, albeit briefly, at what the current macroeconomic paradigm may have to say. -

Wwf Raw May 18 1998

Wwf raw may 18 1998 click here to download Jan 12, WWF: Raw is War May 18, Nashville, TN Nashville Arena The current WWF champs are as follows: WWF Champion: Steve Austin. Apr 22, -A video package recaps how Vince McMahon has stacked the deck against WWF Champion Steve Austin at Over the Edge and the end of last. Monday Night RAW Promotion WWF Date May 18, Venue Nashville Arena City Nashville, Tennessee Previous episode May 11, Next episode May. Apr 9, WWF Monday Night RAW 5/18/ Hot off the heels of some damn good shows I feel that it will continue. Nitro is preempted again and RAW. May 19, Craig Wilson & Jamie Lithgow 'Monday Night Wars' continues with the episodes of Raw and Nitro from 18 May Nitro is just an hour long. May 21, Monday Night Raw: May 18th, Last week, Dude Love was reinvented as a suit-wearing suit (nice one, eh?) and named the number one. Monday Night Raw May 18 Val Venis vs. 2 Cold Scorpio Terry Funk vs. Marc Mero Disciples of Apocalypse vs. LOD Dude Love vs. Dustin Runnells. Jan 5, May 18, – RAW: Val Venis b Too Cold Scorpio, Terry Funk b Marc Mero, The Disciples of Apocalypse b LOD (Hawk & Animal), Dude. Dec 22, Publicly, Vince has ignored the challenge, but WWF as a whole didn't. On Raw, Jim Ross talked shit about WCW for the whole show. X-Pac and. On the April 13, episode of Raw Is War, Dude Love interfered in a WWF World On the May 18 episode of Raw Is War, Vader attacked Kane during a tag .