INTRODUCTION What Are Butterflies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papilio Glaucus, P. Marcellus, P. Philenor, Pieris Rapae, Colias Philo Dice, Antho Caris Genutia, Anaea Andria, Euptychia Gemma

102 REMINGTON: 1952 Central Season Vol.7, nos.3·4 Papilio glaucus, P. marcellus, P. philenor, Pieris rapae, Colias philo dice, Antho caris genutia, Anaea andria, Euptychia gemma. One exception to the general scarcity was the large number of Erynnis brizo and E. juvenalis which were seen clustered around damp spots in a dry branch on April 9. MERRITT counted 67 Erynnis and 2 Papilio glaucus around one such spOt and 45 Erynnis around another. Only one specimen of Incisalia henrici was seen this spring. MERRITT was pleased to find Incisalia niphon still present in a small tract of pine although the area was swept by a ground fire in 1951. Vanessa cardui appeared sparingly from June 12 on, the first since 1947. In the late summer the season appeared normal. Eurema lisa, Nathalis iole, Lycaena thoe, and Hylephila phyleus were common. Junonia coenia was more abundant around Louisville than he has ever seen it. A rarity taken in Louisville this fall was Atlides halesus, the first seen since 1948. The latest seasonal record made by Merritt was a specimen of Colias eury theme flying south very fast on December 7. EDWARD WELLING sent a record of finding Lagoa crispata on June 27 at Covington. Contributors: F. R. ARNHOLD; E. G. BAILEY; RALPH BEEBE; S. M. COX; H. V. DALY; 1. W . GRIEWISCH; J. B. HAYES; R. W. HODGES; VONTA P. HYNES; R. LEUSCHNER; J. R. MERRITT; J. H. NEWMAN; M. C. NIEL SEN; 1. S. PHILLIPS; P. S. REMINGTON; WM. SIEKER; EDWARD VOSS; W. H . WAGNER, JR.; E. C. -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

GIS Handbook Appendices

Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Appendix D Cooperating Agency Codes The following table lists the aerial survey cooperating agencies and codes to be used in the agency1, agency2, agency3 fields of the flown/not flown coverages. The contents of this list is available in digital form (.dbf) at the following website: http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/publications/id/id_guidelines.html 28 Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Code Agency Name AFC Alabama Forestry Commission ADNR Alaska Department of Natural Resources AZFH Arizona Forest Health Program, University of Arizona AZS Arizona State Land Department ARFC Arkansas Forestry Commission CDF California Department of Forestry CSFS Colorado State Forest Service CTAES Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station DEDA Delaware Department of Agriculture FDOF Florida Division of Forestry FTA Fort Apache Indian Reservation GFC Georgia Forestry Commission HOA Hopi Indian Reservation IDL Idaho Department of Lands INDNR Indiana Department of Natural Resources IADNR Iowa Department of Natural Resources KDF Kentucky Division of Forestry LDAF Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry MEFS Maine Forest Service MDDA Maryland Department of Agriculture MADCR Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation MIDNR Michigan Department of Natural Resources MNDNR Minnesota Department of Natural Resources MFC Mississippi Forestry Commission MODC Missouri Department of Conservation NAO Navajo Area Indian Reservation NDCNR Nevada Department of Conservation -

Paysandisia Archon (Burmeister, 1879) - the Castniid Palm Borer (Lepidoptera, Castniidae) Chapter 14: Factsheets for 80 Representative Alien Species David Lees

Paysandisia archon (Burmeister, 1879) - The castniid palm borer (Lepidoptera, Castniidae) Chapter 14: Factsheets for 80 representative alien species David Lees To cite this version: David Lees. Paysandisia archon (Burmeister, 1879) - The castniid palm borer (Lepidoptera, Cast- niidae) Chapter 14: Factsheets for 80 representative alien species. Alien terrestrial arthropods of Europe, 4 (2), Pensoft Publishers, 2010, BioRisk, 978-954-642-555-3. hal-02928701 HAL Id: hal-02928701 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02928701 Submitted on 2 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 990 Edited by Alain Roques & David Lees / BioRisk 4(2): 855–1021 (2010) 14.65 – Paysandisia archon (Burmeister, 1879) - Th e castniid palm borer (Lepidoptera, Castniidae) Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde & David Lees Description and biological cycle: Large dayfl ying moth with clubbed antennae, wingspan 75–120 mm, upperside forewing greenish brown in both sexes, hindwing bright orange with a black band postdiscal to white spots (Photo left). Forewing underside orange, excepting beige tips. Upright fusiform eggs, about 4.7 mm. long and 1.5 mm wide, laid by the female’s extensible ovipositor between mid-June and mid-October. Fertile eggs pink, laid among palm crown fi bres, at the base of leaf rachis. -

List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017

Washington Natural Heritage Program List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017 The following list of animals known from Washington is complete for resident and transient vertebrates and several groups of invertebrates, including odonates, branchipods, tiger beetles, butterflies, gastropods, freshwater bivalves and bumble bees. Some species from other groups are included, especially where there are conservation concerns. Among these are the Palouse giant earthworm, a few moths and some of our mayflies and grasshoppers. Currently 857 vertebrate and 1,100 invertebrate taxa are included. Conservation status, in the form of range-wide, national and state ranks are assigned to each taxon. Information on species range and distribution, number of individuals, population trends and threats is collected into a ranking form, analyzed, and used to assign ranks. Ranks are updated periodically, as new information is collected. We welcome new information for any species on our list. Common Name Scientific Name Class Global Rank State Rank State Status Federal Status Northwestern Salamander Ambystoma gracile Amphibia G5 S5 Long-toed Salamander Ambystoma macrodactylum Amphibia G5 S5 Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Amphibia G5 S3 Ensatina Ensatina eschscholtzii Amphibia G5 S5 Dunn's Salamander Plethodon dunni Amphibia G4 S3 C Larch Mountain Salamander Plethodon larselli Amphibia G3 S3 S Van Dyke's Salamander Plethodon vandykei Amphibia G3 S3 C Western Red-backed Salamander Plethodon vehiculum Amphibia G5 S5 Rough-skinned Newt Taricha granulosa -

Washington Butterfly Association Common Butterflies of the Puget Sound Region and Their Food Plants

Washington Butterfly Association [email protected] Pine White ( Neophasia menapia ) w ww.naba.org/chapters/nabaws / Identification : White with black forewing patch, black veins below. Flight Period : late June – early October, peak in August. Common Butterflies of the Puget Sound Region Favorite Nectar Plants : Goldenrod, and Their Food Plants - By David Droppers Pearly Everlasting, Asters, Thistles. Larval Host Plants : Ponderosa Pine, Western Tiger Swallowtail ( Papilio Lodgepole Pine, Douglas-Fir, among other conifers. rutulus ). Identification : Large. Yellow with black tiger stripes. Cabbage White ( Pieris rapae) Underside with some blue. Flight Identification : White, black wing tips and Period : mid April – late September, spots. Males have one spot, females two peak in June. Favorite Nectar Plants : spots. Flight Period : early March – early Mock Orange, Milkweeds, Thistles, November, peaks in May, July and large showy flowers. Larval Host September. Favorite Nectar Plants: Plants : Native Willows, Quaking Many, especially garden flowers, such as Oregano and Lavender. Aspen and other poplars, Red Alder Larval Host Plants : Garden Brassicae, especially broccoli and cabbage. Anise Swallowtail ( Papilio zelicaon) Identification : Large. Mostly black, Cedar Hairstreak ( Mitoura grynea ) centrally yellow, with row of blue dots Identification : Small. Varying brown above, below buff brown on hindwing. Flight Period : late with violet tint, variable white postmedian line, small tails on March – late September, peaks in May, hindwings. Flight Period : late March – early August, peaks in July-August. Favorite Nectar Plants : May-June. Favorite Nectar Plants : Goldenrods, Yarrow, Many flowers, mostly large and showy. Dandelion, Clovers, Red Flowering Currant. Larval Host Plants : Garden Parsley Larval Host Plants : Western Red Cedar, Incense Cedar and Dill, Angelica, Cow Parsnip, many others. -

Acta Zool. Hung. 53 (Suppl

Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 53 (Suppl. 1), pp. 211–224, 2007 THE DESCRIPTION OF THERITAS GOZMANYI FROM THE ANDES AND ITS SPECTROSCOPIC CHARACTERIZATION WITH SOME NOTES ON THE GENUS (LEPIDOPTERA: LYCAENIDAE: EUMAEINI) BÁLINT, ZS.1, WOJTUSIAK, J.2, KERTÉSZ, K.3 and BIRÓ, L. P.3 1Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum H-1088 Budapest, Baross u. 13, Hungary; E-mail: [email protected] 2Zoological Museum, Jagiellonian University, 30–060 Kraków, Ingardena 6, Poland 3Department of Nanotechnology, Research Institute for Technical Physics and Material Science H-1525 Budapest, P.O. Box 49, Hungary A key for separating sister genera Arcas SWAINSON, 1832 and Theritas HÜBNER, 1818, plus eight nominal species placed in Theritas is given. Three species groups within the latter genus are distinguished. A new species, Theritas gozmanyi BÁLINT et WOJTUSIAK, sp. n. is described form Ecuador. The presence of a discal scent pad on the fore wing dorsal surface and spectral characteristics of the light reflected from the central part of the discal cell were used as charac- ters for discrimination of the new species. Key words: androconial clusters, spectroscopy, structural colours, Theritas species-groups INTRODUCTION The generic name Theritas was established by monotypy for the new species Theritas mavors by HÜBNER (1818). The genus-group name was not in general use until the revision of D’ABRERA (1995), who placed 23 species-group taxa in Theritas on the basis of the character “the pennent-like tail which projects out- wards, and an approximate right angle from, and as a part of, a squared-off projec- tion of the tapered h. -

Acrolepiopsis Assectella

Acrolepiopsis assectella Scientific Name Acrolepiopsis assectella (Zeller, 1893) Synonym: Lita vigeliella Duponchel, 1842 Common Name Leek moth, onion leafminer Type of Pest Moth Taxonomic Position Class: Insecta, Order: Lepidoptera, Family: Acrolepiidae Figures 1 & 2. Adult male (top) and female (bottom) Reason for Inclusion of A. assectella. Scale bar is 1 mm (© Jean-François CAPS Community Suggestion Landry, Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, 2007). Pest Description Eggs: “Roughly oval in shape with raised reticulated sculpturing; iridescent white” (Carter, 1984). Eggs are 0.5 by 1 0.2 mm (< /16 in) (USDA, 1960). Larvae: “Head yellowish brown, sometimes with reddish brown maculation; body yellowish green; spiracles surrounded by sclerotised rings, on abdominal segments coalescent with SD pinacula, these grayish brown; prothoracic and anal plates yellow with brown maculation; thoracic legs yellowish brown’ crochets of abdominal prologs arranged in uniserial circles, each enclosing a short, longitudinal row of 3–5 crochets” 1 (Carter, 1984). Larvae are about 13 to 14 mm (approx. /2 in) long (McKinlay, 1992). Pupae: “Reddish brown; abdominal spiracles on raised tubercles; cremaster abruptly terminated, dorsal lobe with a Figure 3. A. assectella larvae rugose plate bearing eight hooked setae, two rounded ventral on stem of elephant garlic lobes each bearing four hooked setae” (Carter, 1984). The (eastern Ontario, June 2000) (© 1 cocoon is 7 mm (approx. /4 in) long (USDA, 1960). “The Jean-François Landry, cocoon is white in colour and is composed of a loose net-like Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, 2007). structure” (CFIA, 2012). Last updated: August 23, 2016 9 Adults: “15 mm [approx. /16 in wingspan]. Forewing pale brown, variably suffused with blackish brown; terminal quarter sprinkled with white scales; a distinct triangular white spot on the dorsum near the middle. -

Pine Butterfly (Neophasia Menapia) Outbreak in the Malheur National Forest, Blue Mountains, Oregon: Examining Patterns of Defoliation

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Ariadne T. DeMarco for the degree of Master of Science in Sustainable Forest Management presented on March 21, 2014. Title: Pine Butterfly (Neophasia menapia) Outbreak in the Malheur National Forest, Blue Mountains, Oregon: Examining Patterns of Defoliation Abstract approved: David C. Shaw The pine butterfly (Neophasia menapia C. Felder & R. Felder) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) is a relatively host-specific defoliator of ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Dougl. ex Laws). From 2008 to 2012, the Malheur National Forest was subject to an outbreak of pine butterfly in ponderosa pine, peaking at ~100,000 ha of forest visibly defoliated in 2011. Silvicultural- based management guidelines have been used to manage stand resilience to other insect defoliators, but guidelines specific to the pine butterfly are currently lacking. The goal of this study is to examine pine butterfly defoliation patterns to relate stand and tree structure characteristics to inform management guidelines. I randomly sampled 25 stands within ponderosa pine forests delineated as heavily defoliated in 2011 by annual forest health aerial surveys. Within each stand I randomly located three transect plots, 10 x 40m, and measured diameter at breast height (DBH), height, and estimated defoliation for the entirety of all trees > 5cm DBH. Data was analyzed using linear mixed effects models to account for all other determinants of defoliation before measuring variables under study. Defoliation averaged 67% for all trees. Stand density index, stand structure, tree crown class, and level within a tree canopy demonstrated no meaningful effects on mean defoliation. I infer from these results that defoliation levels during pine butterfly outbreaks are not influenced by structural or crown characteristics; virtually all available foliage is consumed in these single host-species stands (though note that ~10% of trees studied showed <50% defoliation levels). -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Bioblitz Butterfly Flight List

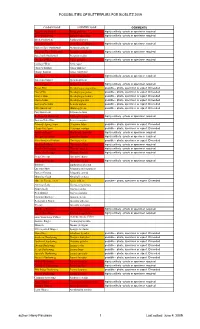

POSSIBILITIES OF BUTTERFLIES FOR BIOBLITZ 2009 COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMENTS Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Zebra Swallowtail Eurytides marcellus highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes Giant Swallowtail Heraclides cresphontes highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Pterourus glaucus Canadian Tiger Swallowtail Pterourus canadensis highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Spicebush Swallowtail Pterourus troilus Checkered White Pontia protodice highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Cabbage White Pieris rapae Clouded Sulphur Colias philodice Orange Sulphur Colias eurytheme Harvester Feniseca tarquinius highly unlikely - photo or specimen required American Copper Lycaena phlaeas Bronze Copper Hyllolycaena hyllus highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Brown Elfin Deciduphagus augustinus possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Hoary Elfin Deciduphagus polios possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Henry's Elfin Deciduphagus henrici possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Frosted Elfin Deciduphagus irus possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Eastern Pine Elfin Incisalia niphon possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Olive Hairstreak Mitoura gryneus possible - photo, specimen or expert ID needed Gray Hairstreak Strymon melinus Red-banded Hairstreak Calycopis cecrops highly unlikely - photo or specimen required Eastern Tailed-Blue Everes comyntas Edwards' Spring Azure -

Colourful Butterfly Wings: Scale Stacks, Iridescence and Sexual Dichromatism of Pieridae Doekele G

158 entomologische berichten 67(5) 2007 Colourful butterfly wings: scale stacks, iridescence and sexual dichromatism of Pieridae Doekele G. Stavenga Hein L. Leertouwer KEY WORDS Coliadinae, Pierinae, scattering, pterins Entomologische Berichten 67 (5): 158-164 The colour of butterflies is determined by the optical properties of their wing scales. The main scale structures, ridges and crossribs, scatter incident light. The scales of pierid butterflies have usually numerous pigmented beads, which absorb light at short wavelengths and enhance light scattering at long wavelengths. Males of many species of the pierid subfamily Coliadinae have ultraviolet-iridescent wings, because the scale ridges are structured into a multilayer reflector. The iridescence is combined with a yellow or orange-brown colouration, causing the common name of the subfamily, the yellows or sulfurs. In the subfamily Pierinae, iridescent wing tips are encountered in the males of most species of the Colotis-group and some species of the tribe Anthocharidini. The wing tips contain pigments absorbing short-wavelength light, resulting in yellow, orange or red colours. Iridescent wings are not found among the Pierini. The different wing colours can be understood from combinations of wavelength-dependent scattering, absorption and iridescence, which are characteristic for the species and sex. Introduction often complex and as yet poorly understood optical phenomena The colour of a butterfly wing depends on the interaction of encountered in lycaenids and papilionids. The Pieridae have light with the material of the wing and its spatial structure. But- two main subfamilies: Coliadinae and Pierinae. Within Pierinae, terfly wings consist of a wing substrate, upon which stacks of the tribes Pierini and Anthocharidini are distinguished, together light-scattering scales are arranged.