Chapter 4: Fog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Read a METAR

How to read a METAR A METAR will look something like this: PHNY 202124Z AUTO 27009KT 1 1/4SM BR BKN016 BKN038 22/21 A3018 RMK AO2 Let’s decipher what each bit of the METAR means. PHNY The first part of the METAR is the airport identifier for the facility which produced the METAR. In this case, this is Lanai Airport in Hawaii. 202124Z Next comes the time and date of issue. The first two digits correspond to the date of the month, and the last 4 digits correspond to the time of issue (in Zulu time). In the example, the METAR was issued on the 20th of the month at 21:24 Zulu time. AUTO This part indicates that the METAR was generated automatically. 27009KT Next comes the wind information. The first 3 digits represent the heading from which the wind is blowing, and the next digits indicate speed in knots. In this case, the wind is coming from a heading of 270 relative to magnetic north, and the speed is 9 knots. Some other wind-related notation you might see: • 27009G15KT – the G indicates gusting. In this case, the wind comes from 270 at 9 knots, and gusts to 15 knots. • VRB09KT – the VRB indicates the wind direction is variable; the wind speed is 9 knots. 1 1/4SM This section of the METAR indicates visibility in statute miles. In this case, visibility is 1 ¼ statute miles. Note that the range is typically limited to 10 statute miles, so a report with 10 statute mile visibility could well indicate a situation with more than 10 statute miles of visibility. -

Improving Lightning and Precipitation Prediction of Severe Convection Using of the Lightning Initiation Locations

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres RESEARCH ARTICLE Improving Lightning and Precipitation Prediction of Severe 10.1002/2017JD027340 Convection Using Lightning Data Assimilation Key Points: With NCAR WRF-RTFDDA • A lightning data assimilation method was developed Haoliang Wang1,2, Yubao Liu2, William Y. Y. Cheng2, Tianliang Zhao1, Mei Xu2, Yuewei Liu2, Si Shen2, • Demonstrate a method to retrieve the 3 3 graupel fields of convective clouds Kristin M. Calhoun , and Alexandre O. Fierro using total lightning data 1 • The lightning data assimilation Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, Nanjing University of Information method improves the lightning and Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, USA, 3Cooperative convective precipitation short-term Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS), NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, University of Oklahoma forecasts (OU), Norman, OK, USA Abstract In this study, a lightning data assimilation (LDA) scheme was developed and implemented in the Correspondence to: Y. Liu, National Center for Atmospheric Research Weather Research and Forecasting-Real-Time Four-Dimensional [email protected] Data Assimilation system. In this LDA method, graupel mixing ratio (qg) is retrieved from observed total lightning. To retrieve qg on model grid boxes, column-integrated graupel mass is first calculated using an Citation: observation-based linear formula between graupel mass and total lightning rate. Then the graupel mass is Wang, H., Liu, Y., Cheng, W. Y. Y., Zhao, distributed vertically according to the empirical qg vertical profiles constructed from model simulations. … T., Xu, M., Liu, Y., Fierro, A. O. (2017). Finally, a horizontal spread method is utilized to consider the existence of graupel in the adjacent regions Improving lightning and precipitation prediction of severe convection using of the lightning initiation locations. -

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems Across the world, many different charts of different formats are used by different governments. These charts can be anything from a simple prognostic chart, used to convey weather forecasts in a simple to read visual manner to the much more complex Wind and Temperature charts used by meteorologists and pilots to determine current and forecast weather conditions at high altitudes. When used properly these charts can be the key to accurately determining the weather conditions in the near future. This Write-Up will provide a brief introduction to several common types of charts. Prognostic Charts To the untrained eye, this chart looks like a strange piece of modern art that an angry mathematician scribbled numbers on. However, this chart is an extremely important resource when evaluating the movement of weather fronts and pressure areas. Fronts Depicted on the chart are weather front combined into four categories; Warm Fronts, Cold Fronts, Stationary Fronts and Occluded Fronts. Warm fronts are depicted by red line with red semi-circles covering one edge. The front movement is indicated by the direction the semi- circles are pointing. The front follows the Semi-Circles. Since the example above has the semi-circles on the top, the front would be indicated as moving up. Cold fronts are depicted as a blue line with blue triangles along one side. Like warm fronts, the direction in which the blue triangles are pointing dictates the direction of the cold front. Stationary fronts are frontal systems which have stalled and are no longer moving. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Precipitation Effects of Giant Cloud Condensation Nuclei Artificially Introduced Into Stratocumulus Clouds

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5645–5658, 2015 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/15/5645/2015/ doi:10.5194/acp-15-5645-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Precipitation effects of giant cloud condensation nuclei artificially introduced into stratocumulus clouds E. Jung1, B. A. Albrecht1, H. H. Jonsson2, Y.-C. Chen3,4, J. H. Seinfeld3, A. Sorooshian5, A. R. Metcalf3,*, S. Song1, M. Fang1, and L. M. Russell6 1Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA 2Center for Interdisciplinary Remotely-Piloted Aircraft Studies, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, USA 3California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA 5Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, and Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA 6Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA *now at: Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, California, USA Correspondence to: E. Jung ([email protected]) Received: 7 November 2014 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 7 January 2015 Revised: 6 April 2015 – Accepted: 11 April 2015 – Published: 22 May 2015 Abstract. To study the effect of giant cloud condensation 1 Introduction nuclei (GCCN) on precipitation processes in stratocumulus clouds, 1–10 µm diameter salt particles (salt powder) were The stratocumulus (Sc) cloud deck is the most persistent released from an aircraft while flying near the cloud top on cloud type in the world, and the variations of the cloud 3 August 2011 off the central coast of California. The seeded amount and the albedo can significantly impact the climate area was subsequently sampled from the aircraft that was system through their radiative effects on the earth system equipped with aerosol, cloud, and precipitation probes and (e.g., Hartmann et al., 1992; Slingo, 1990). -

Touching the Clouds Activity Guide

Touching the Clouds Activity Guide Purpose Provide a mental representation of each cloud type Create a tactile cloud identification chart Overview Individuals will construct and touch a tactile model of common types of clouds to learn how to describe the clouds based on their shape and texture. They will compare their descriptions with the standard classifications using the cloud types identified in the GLOBE Clouds Protocol. Time: 45 minutes to 1 ½ hours, depending on individual’s age Level: All Materials (per person) One large sheet of cardstock (18” x 12”) Tape One set of Braille labels for each cloud type and/or markers One small feather A layered piece of blanket or soft fabric (eight 1’ X 1” pieces) Cotton balls of varied sizes One tissue Organza or a similar material, cut into pieces, one layered 1” x 1” piece Pillow stuffing, one 1” x 1” piece A tsp of sand Three paper clips Liquid glue Scissors Baby Wipes Preparation Use tape to divide the large cardstock sheet in four sections: one for the cloud title at the top and three for the altitudes: using a portrait layout, place three pieces of tape horizontally, from side to side of the sheet. 1. 1” off the upper edge of the sheet 2. 8” off the upper edge of the sheet 1 Steps What to do and how to do it: Making A Tactile Cloud Identification Chart 1. Discuss that clouds come in three basic shapes: cirrus, stratus and cumulus. a. Feel of the 4” feather and describe it; discuss that these wispy clouds are high in the sky and are named cirrus. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

Forecasting of Thunderstorms in the Pre-Monsoon Season at Delhi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Publications of the IAS Fellows Meteorol. Appl. 6, 29–38 (1999) Forecasting of thunderstorms in the pre-monsoon season at Delhi N Ravi1, U C Mohanty1, O P Madan1 and R K Paliwal2 1Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi 110 016, India 2National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, Mausam Bhavan Complex, Lodi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India Accurate prediction of thunderstorms during the pre-monsoon season (April–June) in India is essential for human activities such as construction, aviation and agriculture. Two objective forecasting methods are developed using data from May and June for 1985–89. The developed methods are tested with independent data sets of the recent years, namely May and June for the years 1994 and 1995. The first method is based on a graphical technique. Fifteen different types of stability index are used in combinations of different pairs. It is found that Showalter index versus Totals total index and Jefferson’s modified index versus George index can cluster cases of occurrence of thunderstorms mixed with a few cases of non-occurrence along a zone. The zones are demarcated and further sub-zones are created for clarity. The probability of occurrence/non-occurrence of thunderstorms in each sub-zone is then calculated. The second approach uses a multiple regression method to predict the occurrence/non- occurrence of thunderstorms. A total of 274 potential predictors are subjected to stepwise screening and nine significant predictors are selected to formulate a multiple regression equation that gives the forecast in probabilistic terms. -

An Operational Marine Fog Prediction Model

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE NATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL CENTER OFFICE NOTE 371 An Operational Marine Fog Prediction Model JORDAN C. ALPERTt DAVID M. FEIT* JUNE 1990 THIS IS AN UNREVIEWED MANUSCRIPT, PRIMARILY INTENDED FOR INFORMAL EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION AMONG NWS STAFF MEMBERS t Global Weather and Climate Modeling Branch * Ocean Products Center OPC contribution No. 45 An Operational Marine Fog Prediction Model Jordan C. Alpert and David M. Feit NOAA/NMC, Development Division Washington D.C. 20233 Abstract A major concern to the National Weather Service marine operations is the problem of forecasting advection fogs at sea. Currently fog forecasts are issued using statistical methods only over the open ocean domain but no such system is available for coastal and offshore areas. We propose to use a partially diagnostic model, designed specifically for this problem, which relies on output fields from the global operational Medium Range Forecast (MRF) model. The boundary and initial conditions of moisture and temperature, as well as the MRF's horizontal wind predictions are interpolated to the fog model grid over an arbitrarily selected coastal and offshore ocean region. The moisture fields are used to prescribe a droplet size distribution and compute liquid water content, neither of which is accounted for in the global model. Fog development is governed by the droplet size distribution and advection and exchange of heat and moisture. A simple parameterization is used to describe the coefficients of evaporation and sensible heat exchange at the surface. Depletion of the fog is based on droplet fallout of the three categories of assumed droplet size. -

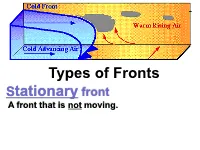

Types of Fronts Stationary Front a Front That Is Not Moving

Types of Fronts Stationary front A front that is not moving. Types of Fronts Cold front is a leading edge of colder air that is replacing warmer air. Types of Fronts Warm front is a leading edge of warmer air that is replacing cooler air. Types of Fronts Occluded front: When a cold front catches up to a warm front. Types of Fronts Dry Line Separates a moist air mass from a dry air mass. A.Cold Front is a transition zone from warm air to cold air. A cold front is defined as the transition zone where a cold air mass is replacing a warmer air mass. Cold fronts generally move from northwest to southeast. The air behind a cold front is noticeably colder and drier than the air ahead of it. When a cold front passes through, temperatures can drop more than 15 degrees within the first hour. The station east of the front reported a temperature of 55 degrees Fahrenheit while a short distance behind the front, the temperature decreased to 38 degrees. An abrupt temperature change over a short distance is a good indicator that a front is located somewhere in between. B. Warm Front. • A transition zone from cold air to warm air. • A warm front is defined as the transition zone where a warm air mass is replacing a cold air mass. Warm fronts generally move from southwest to northeast . The air behind a warm front is warmer and more moist than the air ahead of it. When a warm front passes through, the air becomes noticeably warmer and more humid than it was before. -

Analysis of Lightning and Precipitation Activities in Three Severe Convective Events Based on Doppler Radar and Microwave Radiometer Over the Central China Region

atmosphere Article Analysis of Lightning and Precipitation Activities in Three Severe Convective Events Based on Doppler Radar and Microwave Radiometer over the Central China Region Jing Sun 1, Jian Chai 2, Liang Leng 1,* and Guirong Xu 1 1 Hubei Key Laboratory for Heavy Rain Monitoring and Warning Research, Institute of Heavy Rain, China Meteorological Administration, Wuhan 430205, China; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (G.X.) 2 Hubei Lightning Protecting Center, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-8180-4905 Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019; Published: 1 June 2019 Abstract: Hubei Province Region (HPR), located in Central China, is a concentrated area of severe convective weather. Three severe convective processes occurred in HPR were selected, namely 14–15 May 2015 (Case 1), 6–7 July 2013 (Case 2), and 11–12 September 2014 (Case 3). In order to investigate the differences between the three cases, the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of cloud–ground lightning (CG) flashes and precipitation, the distribution of radar parameters, and the evolution of cloud environment characteristics (including water vapor (VD), liquid water content (LWC), relative humidity (RH), and temperature) were compared and analyzed by using the data of lightning locator, S-band Doppler radar, ground-based microwave radiometer (MWR), and automatic weather stations (AWS) in this study. The results showed that 80% of the CG flashes had an inverse correlation with the spatial distribution of heavy rainfall, 28.6% of positive CG (+CG) flashes occurred at the center of precipitation (>30 mm), and the percentage was higher than that of negative CG ( CG) − flashes (13%). -

Weather & Climate

Weather & Climate July 2018 “Weather is what you get; Climate is what you expect.” Weather consists of the short-term (minutes to days) variations in the atmosphere. Weather is expressed in terms of temperature, humidity, precipitation, cloudiness, visibility and wind. Climate is the slowly varying aspect of the atmosphere-hydrosphere-land surface system. It is typically characterized in terms of averages of specific states of the atmosphere, ocean, and land, including variables such as temperature (land, ocean, and atmosphere), salinity (oceans), soil moisture (land), wind speed and direction (atmosphere), and current strength and direction (oceans). Example of Weather vs. Climate The actual observed temperatures on any given day are considered weather, whereas long-term averages based on observed temperatures are considered climate. For example, climate averages provide estimates of the maximum and minimum temperatures typical of a given location primarily based on analysis of historical data. Consider the evolution of daily average temperature near Washington DC (40N, 77.5W). The black line is the climatological average for the period 1979-1995. The actual daily temperatures (weather) for 1 January to 31 December 2009 are superposed, with red indicating warmer-than-average and blue indicating cooler-than-average conditions. Departures from the average are generally largest during winter and smallest during summer at this location. Weather Forecasts and Climate Predictions / Projections Weather forecasts are assessments of the future state of the atmosphere with respect to conditions such as precipitation, clouds, temperature, humidity and winds. Climate predictions are usually expressed in probabilistic terms (e.g. probability of warmer or wetter than average conditions) for periods such as weeks, months or seasons.