The Elective System Or Prescribed Curriculum: the Controversy in American Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Educational Ethics

Educational Ethics: A Field-Launching Conference Harvard Graduate School of Education May 1-2, 2020 THURSDAY, APRIL 30: Pre-Conference Setting the Stage 9:30-3:30 Graduate student workshop (led by Randall Curren and Harry Brighouse) 4:30-6:00 HGSE Centennial Askwith Forum: Higher Education Ethics in a Global Context (Invitees: Elizabeth Kiss, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Beverly Daniel Tatum) 7:00-9:00 Welcome dinner for Askwith Forum speakers + conference panelists who are available + graduate fellows FRIDAY, MAY 1: Defining the Space 8:15-9:00 Breakfast + Registration 9:00-9:30 Welcome and Framing the Conference 9:30-11:00 Framing Educational Ethics What are some key questions in educational ethics that parents, policy makers, school and district leaders, university leaders and faculty, and/or teachers have been contending with? Why aren’t they sufficiently answered by more general moral and political philosophy, by extant philosophy of education, or by codes of professional ethics? What would be helpful? Neema Avashia, Eighth Grade Civics Teacher, Boston Public Schools Yuli Tamir, President, Shenkar College, Tel Aviv John Silvanus Wilson, Senior Advisor and Strategist to the President, Harvard University; 11th President, Morehouse College Terri Wilson, Assistant Professor in the School of Education, UC-Boulder Moderator: Meira Levinson, Professor of Education, Harvard Graduate School of Education 11:00-11:30 Break 11:30-1:00 Educational Ethics in Context 1: Schools and universities in society How should we think about educational ethics in relation to other social institutions such as politics or economics, and in relation to the historical and cultural context in which educational institutions are constructed and sit? When and how is it appropriate to take the larger context for granted (as much as we may wish it were different) and figure out the ethical demands for educators, schools, educational systems, etc. -

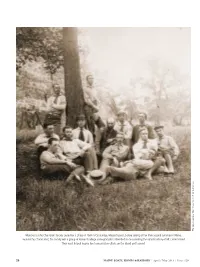

Members of the Champlain Society Posed for a Photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Before Setting Off for Their Second Summer in Maine

Photograph courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society Members of the Champlain Society posed for a photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, before setting off for their second summer in Maine. Founded by Charles Eliot, the society was a group of Harvard College undergraduates interested in documenting the natural history of Mt. Desert Island. Their work helped inspire land conservation efforts on the island and beyond. 26 MAINE BOATS, HOMES & HARBORS | April / May 2014 | Issue 129 Influenced by NATURE Early Maine sailing vacations inspired a land conservation movement BY CATHERINE SCHMITT IN MAY 1871, Charles William and the Deer Isle Thorofare. As they Eliot had been president of Har- made Bass Harbor Light on the third day , by Charles William Eliot I vard University barely two years, out, the fog cleared away. They passed and a widower just as long. He needed Long Ledge and Great Cranberry Island a break, for himself and his two young and sailed into Southwest Harbor. sons, a “thorough vacation” in the open This cruise and summer of camping, air, as he wrote to a friend. the first of many, helped instill in Eliot, He found means in the Jessie, a 33- and especially his son Charles, a sense of foot sloop, and began planning a sailing place that would have a lasting impact Charles Eliot Landscape Architect and camping trip to Maine, “down on the Mt. Desert region and beyond. From Mount Desert way.” Described as “a very The younger Charles Eliot, who became Charles Eliot in 1897 at age 33. pretty boat and tolerably fast,” the Jessie a landscape architect and partner in the and crew made a few warm-up excur- firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., ple to enjoy the same experience today. -

Jared Sparks

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN THE REVEREND JARED SPARKS “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY WALDEN: His only books were an almanac and an arithmetic, in which PEOPLE OF last he was considerably expert. The former was a sort WALDEN of cyclopaedia to him, which he supposed to contain an abstract of human knowledge, as indeed it does to a considerable extent. ALEK THERIEN JARED SPARKS “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project The People of Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX REVEREND JARED SPARKS JARED SPARKS PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN 1789 May 10, Sunday: Jared Sparks was born in Wilmington, Connecticut. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT The People of Walden “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX REVEREND JARED SPARKS JARED SPARKS PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN 1809 Jared Sparks matriculated at Phillips Exeter Academy. LIFE IS LIVED FORWARD BUT UNDERSTOOD BACKWARD? — NO, THAT’S GIVING TOO MUCH TO THE HISTORIAN’S STORIES. LIFE ISN’T TO BE UNDERSTOOD EITHER FORWARD OR BACKWARD. “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project The People of Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX REVEREND JARED SPARKS JARED SPARKS PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN 1811 Fall: At Harvard College’s divinity school, Dr. Henry Ware, Sr., Hollis Professor, began a course of exercises with the resident Students in Divinity: Messrs. John Emery Abbot (A.B. Bowdoin College 1810) Joseph Allen (A.B. 1811) John Dudley Andrews (A.B. 1810) Lemuel Capen (A.B. 1810) Jonathan Peale Dabney (A.B. 1811) David Damon (A.B. 1811) Charles Eliot (A.B. 1809) George Bethune English (A.B. -

George Bucknam Dorr Brief Life of a Persistent Conservationist: 1853-1944 by Steven Pavlos Holmes

VITA George Bucknam Dorr Brief life of a persistent conservationist: 1853-1944 by steven pavlos holmes uly 8 marked the centennial of the founding of the Sieur de tween the Yard and the Charles River. These tasks honed skills of Monts National Monument in Maine, which within a few years planning, negotiation, and administration on which he drew when Jbecame the new National Park Service’s first Eastern property. he turned to conserving open space on Mount Desert Island. The creation of what is known today as Acadia National Park was In the 1890s, living at his family’s home on the island, Dorr devel- spearheaded by a wealthy Bostonian, George Bucknam Dorr, A.B. oped a real interest and expertise in landscape gardening, founding 1874, who also served as its first superintendent. the Mt. Desert Nurseries, working on other landscaping and con- Dorr’s Brahmin family lived in bucolic Jamaica Plain until he was servation projects there (sometimes alongside future landscape ar- seven, and he wrote later, “My earliest recollections are concerned chitect Beatrix Farrand), and, further afield, advising friends such with gardens….” Of his grandfather’s home in rural Canton, he re- as the novelist Edith Wharton on her estate in the Berkshires. called: “There, in real country, with woods and a lake for neigh- In 1891, President Eliot’s son Charles, a landscape architect, and bors, dogs and horses for companions, my brother and I grew up, others founded The Trustees of Reservations in Massachusetts springs and falls, till college days.” His mother read him works by “for the purpose of acquiring, holding, arranging, maintaining and the Lake Poets, and “Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey, Carlyle opening to the public, under suitable regulations, beautiful and and Ruskin came to be part of me, grew into my being.” In 1868, the historical places and tracts of land” within the Commonwealth. -

Biography Eliot – Charles William Eliot (1834-1926)

Biography Eliot – Charles William Eliot (1834-1926) Father: Eliot - Samuel Atkins Eliot I (1798-1862) Mother: Mary Lyman (1802-1875) Birth Date: March 20, 1834 Born at: Boston, Massachusetts Cousin of poet T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) – Thomas Stearns Eliot Significant Education: 1949: Graduated from Boston Latin School 1853: Graduated from Harvard University 1869: Williams College and Princeton LL. D. 1870: Yale University LL. D. 1902: Johns Hopkins LL. D. Later an honorary member of Hasty Pudding Spouse Name: Ellen Derby Peabody (1836-1869) Spouse Parents: Ephraim Peabody (1776-1816) and Mary Jane Derby (1807-1892) Wedding Date: October 27, 1858 Wedding Place: Boston, Massachusetts 2nd Spouse Name: Grace Mellen Hopkinson (1846-1924) 2nd Spouse Parents: Thomas Hopkinson (1804-1856) and Corinna Aldrich Prentiss (1805-1883) 2nd Wedding Date: October 30, 1877 2nd Wedding Place: Cambridge, Massachusetts Occupation: Educator Noted for changing Harvard into a research university and changing education in America. Taught school for several years after graduation and then spent two years studying educational systems in Europe. 1869-1909: President of Harvard University: longest term of any president of the university. Author of several books. See: “The Forgotten Millions II – John Gilley” by Charles W. Eliot, published in “The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine” Vol. LIX, New Series, Vol. XXXVII, November, 1899, to April, 1900. First published as “John Gilley: Maine Farmer and Fisherman,” Century Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1899. See: John Gilley – Charles W. Eliot.pdf See: “Charles William Eliot,” Harvard University site, 2015, Accessed online 04/05/2015; http://www.harvard.edu/history/presidents/eliot See: Origin of Acadia National Park and Memorial to: “The Memorials of Acadia National Park” by Donald P. -

Harvard Barbarians” Catherine Schmitt University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Sea Grant Publications Maine Sea Grant 2014 Visionary Science of the “Harvard Barbarians” Catherine Schmitt University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub Part of the American Studies Commons, Life Sciences Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Schmitt, Catherine, "Visionary Science of the “Harvard Barbarians”" (2014). Maine Sea Grant Publications. 45. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Sea Grant Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Members of the Champlain Society pose for the camera in Cambridge, May 1881. Collection of the Mount Desert Island Historical Society Visionary Science of the “Harvard Barbarians” Catherine Schmitt It was the fifth of July, the year 1880. The forty-four-foot sloop Sunshine lay at anchor in Wasgatt Cove, where Hadlock Brook emptied into Somes Sound. On shore, in a field just north of Asa Smallidge’s house, eight young men were cutting the grass and setting up canvas tents. From the boat they unloaded shotguns and nets, fishing rods and glass bottles, small wooden 17 boxes and stacks of books and notepaper. They cut a sapling into a pole, and raised a red, white, and blue flag while cheering, “Yo-ho! Yo-ho! Yo-ho!” Over the next two months, the young men made daily excursions, on foot and by boat, around Mount Desert Island. -

Winter 2007 Volume 12 No

27_2141COV 12/12/07 2:55 PM Page c1 Winter 2007 Volume 12 No. 3 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities 27_2141COV 12/12/07 2:55 PM Page c2 Purchase Your Park Pass! Whether walking, bicycling, driving, or riding the fare-free Island Explorer through the park, all must pay the entrance fee. The Acadia National Park $20 weekly pass ($10 in the shoulder seasons) and $40 annual pass are available at the following locations in Maine: Open Year-Round • ACADIA NATIONAL PARK HEADQUARTERS (on the Eagle Lake Road/Rte. 233 in Bar Harbor) Open May – November • HULLS COVE VISITOR CENTER • THOMPSON ISLAND INFORMATION STATION • SAND BEACH ENTRANCE STATION • BLACKWOODS CAMPGROUND • SEAWALL CAMPGROUND • JORDAN POND AND CADILLAC MTN. GIFT SHOPS • MOUNT DESERT CHAMBER OF COMMERCE • VILLAGE GREEN BUS CENTER Your park pass purchase makes possible vital maintenance projects in Acadia. Blagden Tom 27_2141INS 12/18/07 1:48 PM Page 1 President’s Column COMPLETING THE VISION ver Thanksgiving week, my family have been able to discover more environ- and I traveled to California to visit mentally-friendly travel options in the Los Ocolleges and a national park or two. Angeles area, we wouldn’t have seen We poked around Fort Point in San Joshua Tree. Francisco, walked small among giant Which brings me to our choices here at Redwoods, watched elephant seals on a pro- home. During Acadia’s busiest season, resi- tected beach along the Pacific Coast Highway, dents, visitors, and commuters have the and explored the desert at Joshua Tree ability to travel to, through, and around the National Park. -

![Proceedings Volume 12 – 1917 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2112/proceedings-volume-12-1917-pdf-4872112.webp)

Proceedings Volume 12 – 1917 [PDF]

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 12, 1917 Contents: ● Title Page (pdf) ● Table of Contents (pdf) ● Officers ● Proceedings ○ Fortieth Meeting ○ Forty-First Meeting ○ Forty-Second Meeting ● Papers ○ Class Day, Commencement, and Phi Beta Kappa Day, 1829 ○ Archibald Murray Howe By Samuel McChord Crothers, S.T.D. ○ Personal Recollections of Dr.Morrill Wyman, Professor Dunbar, and Professor Shaler By Charles William Eliot, L.L.D. ○ Longfellow's Poems on Cambridge and Greater Boston By Dorothy Henderson ● Annual Report of Secretary and Council ● Annual Report of Curator ● Annual Report of Treasurer ● Necrology ○ Robert Job Melledge ○ Joseph Hodges Choate ○ Henry Oscar Houghton ○ Anne Theresa Morison ● Members ● By-Laws ● Memorandum on the Vassall Portraits, Etc. OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 1916-1917 President ................................... WILLIAM ROSCOE THAYER ANDREW McFARLAND DAVIS WORTHINGTON CHAUNCY FORD Vice-Presidents ........................ HOLLIS RUSSELL BAILEY Secretary ................................... SAMUEL FRANCIS BATCHELDER Treasurer ................................... HENRY HERBERT EDES Curator ...................................... EDWARD LOCKE GOOKIN The Council HOLLIS RUSSELL BAILEY EDWARD LOCKE GOOKIN SAMUEL FRANCIS BATCHELDER MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI FRANK GAYLORD COOK GEORGE HODGES RICHARD HENRY DANA WILLIAM COOLIDGE LANE HENRY HERBERT EDES ALICE MARY LONGFELLOW WORTHINGTON CHAUNCEY FORD FRED NORRIS ROBINSON WILLIAM ROSCOE THAYER PROCEEDINGS OF THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY FORTIETH MEETING -

The Life of Benner C. Turner a Dissertation

I am Leaving and not Looking Back: The Life of Benner C. Turner A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Travis D. Boyce June 2009 © 2009 Travis D. Boyce. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled I am Leaving and not Looking Back: The Life of Benner C. Turner by TRAVIS D. BOYCE has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and the College of Education by Francis E. Godwyll Assistant Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, College of Education 3 ABSTRACT BOYCE, TRAVIS D., Ph.D., June 2009, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies I am Leaving and not Looking Back: The Life of Benner C. Turner (297 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Francis E. Godwyll This study examines the life of Benner Creswill Turner, who was president of South Carolina State College (State College) from 1950 to 1967. On February 8, 1968 there were shootings by police at South Carolina State College, called the Orangeburg Massacre. The prevalent opinion is that the indirect cause of the shootings was due to the poor leadership of the administration at the college, particularly of President Turner. Thus history up to this point has viewed him in a negative manner. However, a new thread of literature has re-examined the lives and administrations of Turner’s contemporaries, placing them and their legacies in a different perspective. Thus this study examined Turner’s legacy and his life outside of the presidency of State College. -

U.S. Higher Education Reform Origins and Impact of Student Curricular

International Journal of Educational Development 61 (2018) 1–4 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Educational Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijedudev U.S. higher education reform: Origins and impact of student curricular T choice ⁎ Robert W. Elliotta, , Valerie Osland Patonb a School of Foreign Languages, Linyi University, Shandong Province, China b Higher Education, College of Education, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Charles W. Eliot’s revision of curriculum through the elective system has had significant influence on U.S. higher Electives education. Contemporary concerns about constrained resources and “efficiency” efforts have called into question Curriculum reform the value of investments in diverse course and degree offerings. This summary of Eliot’s elective system and its Charles william eliot impact on U.S. higher education curricula offers a historical perspective to inform contemporary discourse in a time of reform. Eliot’s inaugural speech and introduction of the elective system are examined, including the context for its introduction, the challenges incurred during implementation, and the benefits it has yielded for U.S. higher education and society. 1. U.S. higher education reform: Origins and impact of student into higher education was one of the most monumental transformations curricular choice in higher education in the U.S. (James, 1930; Wagner, 1950; Rudolph, 1990; Thelin, 2011). The elective system was not a new concept to In the current milieu of constrained resources and “efficiency” dis- colleges when Eliot took office in 1869: George Ticknor, Eliot’s uncle, course that pervade higher education in the United States, investments had introduced the idea of electives in 1825 (Gaff et al., 1997; Hawkins, in diverse course and degree offerings have been questioned by external 1966; Kuehnemann, 1909). -

The Man Without a Country Edward Everett Hale

The Man without a Country Edward Everett Hale The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vol. X, Part 6. Selected by Charles William Eliot Copyright © 2001 Bartleby.com, Inc. Bibliographic Record Contents Biographical Note Criticism and Interpretation By Henry Seidel Canby The Man without a Country Biographical Note THE NAME of Edward Everett Hale suggests his distinguished ancestry. The son of Nathan Hale, proprietor and editor of the Boston “Daily Advertiser,” he was a nephew of Edward Everett, orator, statesman, and diplomat, and a grandnephew of the Revolutionary hero, Nathan Hale. He was born in Boston on April 3, 1822, and after graduating from Harvard in 1839 became pastor of the Church of the Unity, Worcester, Massachusetts. From 1856 till 1899 he ministered to the South Congregational (Unitarian) Church in Boston; and in 1903 became chaplain of the United States Senate. He died at Roxbury, Massachusetts, June 10, 1909, after a career of extraordinary activity and immense influence. Hale was a power in many fields besides literature—in religion, politics, and in social betterment. He was one of the most prominent exponents of the liberal theology that was represented by New England Unitarianism. He took an active part in the anti-slavery movement. A great variety of good causes enlisted his sympathy, and he did substantial service in the cause of popular education. In his Lowell Institute lectures in 1869 he first propounded his famous saying, “Look up and not down, look forward and not back, look out and not in, and lend a hand.” This highly characteristic utterance he took for the motto of his story, “Ten Times One is Ten”; and its influence is testified to by the “Lend-a-Hand Clubs,” “Look-up Legions,” and the like, formed among the young for moral and social improvement. -

The Newsletter of the T. S. Eliot Society “Prufrock” and the Ether Dome

Time Present The Newsletter of the T. S. Eliot Society Number 71 Summer 2010 “Prufrock” and the Ether Dome Sarah Stanbury College of the Holy Cross Contents One of the most famous objects in twentieth-century poetry is a table supporting an “Prufrock” and the Ether etherized patient: “Let us go then, you and I / When the evening is spread out against Dome by Sarah Stanbury ..... 1 the sky/ Like a patient etherized upon a table.” Eliot’s table is apposite for the sky, the backdrop or support for a sunset: This simile comprises arguably one of the most News .................................... 2 egregious pairings in American literature. Categories cross as the immaterial evening Program: T. S. Eliot Society and sky are forced into a relationship with the material body and table; the scene Annual Meeting ................... 3 floats in space, yet in floating it comes to rest on the table that ends the sentence. The table is both essential and inert—a support, in fact, for the structure of the metaphor A Companion to T. S. Eliot, in its entirety: everything comes to rest on it. ed. David E. Chinitz— “Prufrock’s” table also places the poem geographically and makes regional Reviewed by Suzanne W. claims. Eliot’s wanderings around Boston inspired many of his early poems, “Pru- Churchill .............................. 4 frock” among them, and those urban walks may well have brought him past the Mas- sachusetts General Hospital’s famous Ether Dome, site of the first demonstration of Origins of Literary Modern- ether in 1846 (Fig. 1). This event, a foundational moment in the development of ism, ed.