The Man Without a Country Edward Everett Hale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Elective System Or Prescribed Curriculum: the Controversy in American Higher Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 471 740 HE 035 573 AUTHOR Denham, Thomas J. TITLE The Elective System or Prescribed Curriculum: The Controversy in American Higher Education. PUB DATE 2002-08-00 NOTE 17p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Curriculum Development; *Educational History; Educational Trends; *Elective Courses; *Higher Education; *Required Courses IDENTIFIERS *United States ABSTRACT This paper traces the development of curriculum in higher education in the United States. A classical education based on the seven liberal arts was the basis of the curriculum for the early colonial colleges. In its earliest days, the curriculum was relevant to the preparation of students for the professions of the period. Over time, the curriculum evolved and was adapted to correspond to trends in U.S. society, but the colleges did not change the curriculum without intense debate and grave reservations. The tension between a prescribed course of study and the elective principle has cycled through the history of U.S. higher education. The elective system was both a creative and destructive educational development in the post-Civil War era. Eventually, the curriculum changed to a parallel course of study: the traditional classical education and the more modern, practical program. By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. curriculum had evolved into a flexible and diverse wealth of courses well beyond the scope of the colonial curriculum. This evolution moved the university into the mainstream of U.S. life. The debate over prescribed curriculum versus electives continues to generate lively discussion today. (Contains 12 references.)(SLD) THE ELECTIVE SYSTEM OR PRESCRIBED CURRICULUM: THE CONTROVERSY IN AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION Emergence of Higher Education in America Thomas J. -

Edward Channing's Writing Revolution: Composition Prehistory at Harvard

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2017 EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 Bradfield dwarE d Dittrich University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Dittrich, Bradfield dwarE d, "EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 163. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH B.A. St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2003 M.A. Salisbury University, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May 2017 ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2017 Bradfield E. Dittrich iii EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH This dissertation has been has been examined and approved by: Dissertation Chair, Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Thomas Newkirk, Professor Emeritus of English Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Marcos DelHierro, Assistant Professor of English Alecia Magnifico, Assistant Professor of English On April 7, 2017 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Hale and Hale Family Papers in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Hale and Hale Family Papers in the Archives of American Art Judy Ng Processing of this collection was funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2013 August 26 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Materials, circa 1875-1925................................................... 5 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1861-1951............................................................ 6 Series 3: Writings, 1878-1933................................................................................. -

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the HBSC Collection

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center’s Collections Finding Aid To schedule a research appointment, please call the Collections Manager at 860.522.9258 ext. 313 or email [email protected] Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Stowe Center's Collection Note: See end of document for manuscript type definitions. Manuscript type & Recipient Title Date Place length Collection Summary Other Information [Stowe's first known letter] Ten year-old Harriet Beecher writes to her older brother Edward attending Yale. She would like to see "my little sister Isabella". Foote family news. Talks of spending the Nutplains summer at Nutplains. Asks him to write back. Loose signatures of Beecher, Edward (1803-1895) 1822 March 14 [Guilford, CT] ALS, 1 pp. Acquisitions Lyman Beecher and HBS. Album which belonged to HBS; marbelized paper with red leather spine. First written page inscribed: Your Affectionate Father Lyman At end, 1 1/2-page mss of a 28 verse, seven Beecher Sufficient to the day is the evil thereof. Hartford Aug 24, stanza poem, composed by Mrs. Stowe, 1840". Pages 2 and 3 include a poem. There follow 65 mss entitled " Who shall not fear thee oh Lord". poems, original and quotes, and prose from relatives and friends, This poem seems never to have been Katharine S. including HBS's teacher at Miss Pierece's school in Litchfield, CT, published. [Pub. in The Hartford Courant Autograph Bound mss, 74 Day, Bound John Brace. Also two poems of Mrs. Hemans, copied in HBS's Sunday Magazine, Sept., 1960].Several album 1824-1844 Hartford, CT pp. -

Nancy Hale Bibliography

Nancy Hale: A Bibliography Introduction Despite a writing career spanning more than a half century and marked by an extensive amount of published material, no complete listing exists of the works of Nancy Hale. Hale is recognized for capturing both the mentality of a certain level of woman and the aura of a period, glimpsed in three distinctly different areas of the country: Boston, New York, and the South. The three locations are autobiographical, drawing first on the New England of Hale’s birth in 1908 where she remained for her first twenty years, followed by nearly a decade in New York City while she pursued her career, and eventually shifting during the late 1930s to Virginia where she remained for the rest of her life. Those three locales that she understood so well serve exclusively as backdrops for her fiction throughout her long career. Childhood years are always critical to what we become, and Hale’s background figures prominently in her life and her writing. She slipped, an only child, into a distinguished line of New England forebears, marked by the illustrious patriot Nathan Hale and including such prominent writers as grandfather Edward Everett Hale, author of “The Man Without a Country,” and great aunts Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) and Lucretia Peabody Hale (The Peterkin Papers). Her heritage connects her solidly to America’s literary beginnings and repeatedly shapes her own writings, resulting eventually in a publisher’s invitation to edit the significant literature of New England, which results in A New England Discovery. The second geographical site in which Hale sets her fiction, again affords a sensitive representation of an era and its players. -

1 Educational Ethics

Educational Ethics: A Field-Launching Conference Harvard Graduate School of Education May 1-2, 2020 THURSDAY, APRIL 30: Pre-Conference Setting the Stage 9:30-3:30 Graduate student workshop (led by Randall Curren and Harry Brighouse) 4:30-6:00 HGSE Centennial Askwith Forum: Higher Education Ethics in a Global Context (Invitees: Elizabeth Kiss, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Beverly Daniel Tatum) 7:00-9:00 Welcome dinner for Askwith Forum speakers + conference panelists who are available + graduate fellows FRIDAY, MAY 1: Defining the Space 8:15-9:00 Breakfast + Registration 9:00-9:30 Welcome and Framing the Conference 9:30-11:00 Framing Educational Ethics What are some key questions in educational ethics that parents, policy makers, school and district leaders, university leaders and faculty, and/or teachers have been contending with? Why aren’t they sufficiently answered by more general moral and political philosophy, by extant philosophy of education, or by codes of professional ethics? What would be helpful? Neema Avashia, Eighth Grade Civics Teacher, Boston Public Schools Yuli Tamir, President, Shenkar College, Tel Aviv John Silvanus Wilson, Senior Advisor and Strategist to the President, Harvard University; 11th President, Morehouse College Terri Wilson, Assistant Professor in the School of Education, UC-Boulder Moderator: Meira Levinson, Professor of Education, Harvard Graduate School of Education 11:00-11:30 Break 11:30-1:00 Educational Ethics in Context 1: Schools and universities in society How should we think about educational ethics in relation to other social institutions such as politics or economics, and in relation to the historical and cultural context in which educational institutions are constructed and sit? When and how is it appropriate to take the larger context for granted (as much as we may wish it were different) and figure out the ethical demands for educators, schools, educational systems, etc. -

Edward Everett Hale Brief Life of a Science-Minded Writer and Reformer: 1822-1909 by Jeffrey Mifflin

VITA Edward Everett Hale Brief life of a science-minded writer and reformer: 1822-1909 by jeffrey mifflin arvard witnessed a wave of enthusiasm for photogra- Boston was “the first likeness of a human being...taken in Massa- phy in the spring of 1839, inspired by the restlessly inquir- chusetts.” That venue seems to foreshadow his future role as the Hing mind of senior Edward Everett Hale. That January, in church’s Unitarian minister (1856-1899); the congregation he led France and England, Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Tal- for 43 years strongly supported his activism. bot had announced their independently discovered means of pre- Hale was a wide-ranging social reformer, shaped perhaps by the serving the images visible in a camera obscura. Daguerre withheld political discussions overheard at home as he grew up. A lifelong important details until granted a government pension, but Talbot, aversion to rote learning prompted his repeated criticism of the eager to bolster his claim to have invented photography, described formal education of his day; he encouraged his friends to let their his materials and methods fully. Instructions soon crossed the sons learn “by overhearing, by looking on, by trying experiments, Atlantic in his privately printed pamphlet and in scientific jour- and by example.” His own writings for children, such as How to Do nals, prompting undergraduates to “photogenise” with scraps of It (1895), encouraged young minds to be optimistic about what they smooth-surfaced writing paper brushed with nitrate of silver. The could accomplish, and to cultivate “vital power” in readiness for “photogenic drawing” Ned Hale successfully produced that spring, facing life’s problems. -

The Winslows of Boston

Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV FAMILY MEMORIAL The Winslows of Boston Isaac Winslow Margaret Catherine Winslow IN FIVE VOLUMES VOLUME IV Boston, Massachusetts 1837?-1873? TRANSCRIBED AND EDITED BY ROBERT NEWSOM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 2009-10 Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV Editorial material Copyright © 2010 Robert Walker Newsom ___________________________________ All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this work, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission from the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV A NOTE ON MARGARET’S PORTION OF THE MANUSCRIPT AND ITS TRANSCRIPTION AS PREVIOUSLY NOTED (ABOVE, III, 72 n.) MARGARET began her own journal prior to her father’s death and her decision to continue his Memorial. So there is some overlap between their portions. And her first entries in her journal are sparse, interrupted by a period of four years’ invalidism, and somewhat uncertain in their purpose or direction. There is also in these opening pages a great deal of material already treated by her father. But after her father’s death, and presumably after she had not only completed the twenty-four blank leaves that were left in it at his death, she also wrote an additional twenty pages before moving over to the present bound volumes, which I shall refer to as volumes four and five.* She does not paginate her own pages. I have supplied page numbers on the manuscript itself and entered these in outlined text boxes at the tops of the transcribed pages. -

Nathan Hale Parents Fight Transfer 643-0304

to — MANCHESTER HERALD. Tuesday, Nov. 29, 1988 B ig lo af New place Desserts Aquifer discussion Kelly setting up wishbone Colorful sweets "A Winner Every Day... Monday thru Saturday” already under fire /3 at Southington High School /19 that rival, mama’s /13 MANCHESTERHONDA 24 ADAMS ST. 646-3515 Your *25 check Is w aiting at MANc>€STEKHc>jr.\lf your license num ber appears som ew here In the classified colum ns today... INVITATION TO 8ID WANTED TO The Manchester Public APARTMENTS Schools solicits bids for Rsntals FOR RENT RUY/niADE BOILER RETUBIN6 AT MANCHESTER HIGH S p ecio lisi SCHOOL for the 19l$-1ft9 MANCHESTER. Second school year. Sealed bids will ROOMS floor. December 1st oc Old furniture, clocks, • 9*________________ ____ wl be received until December FOR RENT cupancy. 2 bedrooms, 4, 19RS, 2:00 P .M ., at which oriental rugs, lamps, tima they will be publicly all appliances, nice paintings, coins, je lianrhpBtpr HpralJi opened. The right Is reserved MANCHESTER. Room In neighborhood. One i M d a i A N i m e n CMPENTRY/ HEATING/ MI8CELLME 0U8 to ralect any and oil bids. quiet rooming house. months security. $575 welry, glads & china. I SE R V IC E S PLU M BIN G SE R V IC E S Specifications and bid forms Off street parking. $80 plus utilities. 569-2147 Will pay cash. Please ISSJRERIODELINe may be secured at the Busi I per week. 646-1686 or or 228-4408. call, 646-8496. ness Office, 45 North School 569-3018._____________ n m m m m / n m 6S L Building Molnte Street, Manchester, Connec Wednesday, Nov. -

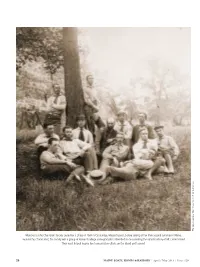

Members of the Champlain Society Posed for a Photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Before Setting Off for Their Second Summer in Maine

Photograph courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society Members of the Champlain Society posed for a photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, before setting off for their second summer in Maine. Founded by Charles Eliot, the society was a group of Harvard College undergraduates interested in documenting the natural history of Mt. Desert Island. Their work helped inspire land conservation efforts on the island and beyond. 26 MAINE BOATS, HOMES & HARBORS | April / May 2014 | Issue 129 Influenced by NATURE Early Maine sailing vacations inspired a land conservation movement BY CATHERINE SCHMITT IN MAY 1871, Charles William and the Deer Isle Thorofare. As they Eliot had been president of Har- made Bass Harbor Light on the third day , by Charles William Eliot I vard University barely two years, out, the fog cleared away. They passed and a widower just as long. He needed Long Ledge and Great Cranberry Island a break, for himself and his two young and sailed into Southwest Harbor. sons, a “thorough vacation” in the open This cruise and summer of camping, air, as he wrote to a friend. the first of many, helped instill in Eliot, He found means in the Jessie, a 33- and especially his son Charles, a sense of foot sloop, and began planning a sailing place that would have a lasting impact Charles Eliot Landscape Architect and camping trip to Maine, “down on the Mt. Desert region and beyond. From Mount Desert way.” Described as “a very The younger Charles Eliot, who became Charles Eliot in 1897 at age 33. pretty boat and tolerably fast,” the Jessie a landscape architect and partner in the and crew made a few warm-up excur- firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., ple to enjoy the same experience today. -

Edward Everett Hale

PEOPLE ALMOST MENTIONED IN THE MAINE WOODS: REVEREND EDWARD EVERETT HALE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project People of Maine Woods: Rev. Edward Everett Hale HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF MAINE WOODS REVEREND EDWARD EVERETT HALE THE MAINE WOODS: Ktaadn, whose name is an Indian word signifying highest land, was first ascended by white men in 1804. It was visited by Professor J.W. Bailey of West Point in 1836; by Dr. Charles T. Jackson, the State Geologist, in 1837; and by two young men from Boston in 1845. All these have given accounts of their expeditions. Since I was there, two or three other parties have made the excursion, and told their stories. Besides these, very few, even among backwoodsmen and hunters, have ever climbed it, and it will be a long time before the tide of fashionable travel sets that way. The mountainous region of the State of Maine stretches from near the White Mountains, northeasterly one hundred and sixty miles, to the head of the Aroostook River, and is about sixty miles wide. The wild or unsettled portion is far more extensive. So that some hours only of travel in this direction will carry the curious to the verge of a primitive forest, more interesting, perhaps, on all accounts, than they would reach by going a thousand miles westward. CHARLES TURNER, JR. JACOB WHITMAN BAILEY DR. CHARLES T. JACKSON EDWARD EVERETT HALE WILLIAM FRANCIS CHANNING HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF MAINE WOODS REVEREND EDWARD EVERETT HALE 1822 Edward Everett Hale was born in Boston, the son of the editor and railroad manager Nathan Hale, and a descendant of the Captain Nathan Hale who had been hung by the Army during the Revolutionary War.