W. Ford Doolittle: Evolutionary Provocations and a Pluralistic Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

2004 Albert Lasker Nomination Form

albert and mary lasker foundation 110 East 42nd Street Suite 1300 New York, ny 10017 November 3, 2003 tel 212 286-0222 fax 212 286-0924 Greetings: www.laskerfoundation.org james w. fordyce On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination Chairman neen hunt, ed.d. for the 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. President mrs. anne b. fordyce The Awards will be offered in three categories: Basic Medical Research, Clinical Medical Vice President Research, and Special Achievement in Medical Science. This is the 59th year of these christopher w. brody Treasurer awards. Since the program was first established in 1944, 68 Lasker Laureates have later w. michael brown Secretary won Nobel Prizes. Additional information on previous Lasker Laureates can be found jordan u. gutterman, m.d. online at our web site http://www.laskerfoundation.org. Representative Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards Program Nominations that have been made in previous years may be updated and resubmitted in purnell w. choppin, m.d. accordance with the instructions on page 2 of this nomination booklet. daniel e. koshland, jr., ph.d. mrs. william mccormick blair, jr. the honorable mark o. hatfied Nominations should be received by the Foundation no later than February 2, 2004. Directors Emeritus A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored. The 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards will be presented at a luncheon ceremony given by the Foundation in New York City on Friday, October 1, 2004. Sincerely, Joseph L. Goldstein, M.D. Chairman, Awards Jury Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards ALBERT LASKER MEDICAL2004 RESEARCH AWARDS PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE AWARDS The major purpose of these Awards is to recognize and honor individuals who have made signifi- cant contributions in basic or clinical research in diseases that are the main cause of death and disability. -

Moore Noller

2002 Ada Doisy Lectures Ada Doisy Lecturers 2003 in BIOCHEMISTRY Sponsored by the Department of Biochemistry • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Dr. Peter B. 1970-71 Charles Huggins* and Elwood V. Jensen A76 1972-73 Paul Berg* and Walter Gilbert* Moore 1973-74 Saul Roseman and Bruce Ames Department of Molecular carbonyl Biophysics & Biochemistry Phe 1974-75 Arthur Kornberg* and Osamu Hayaishi Yale University C75 1976-77 Luis F. Leloir* New Haven, Connecticutt 1977-78 Albert L. Lehninger and Efraim Racker 2' OH attacking 1978-79 Donald D. Brown and Herbert Boyer amino N3 Tyr 1979-80 Charles Yanofsky A76 4:00 p.m. A2486 1980-81 Leroy E. Hood Thursday, May 1, 2003 (2491) 1983-84 Joseph L. Goldstein* and Michael S. Brown* Medical Sciences Auditorium 1984-85 Joan Steitz and Phillip Sharp* Structure and Function in 1985-86 Stephen J. Benkovic and Jeremy R. Knowles the Large Ribosomal Subunit 1986-87 Tom Maniatis and Mark Ptashne 1988-89 J. Michael Bishop* and Harold E. Varmus* 1989-90 Kurt Wüthrich Dr. Harry F. 1990-91 Edmond H. Fischer* and Edwin G. Krebs* 1993-94 Bert W. O’Malley Noller 1994-95 Earl W. Davie and John W. Suttie Director, Center for Molecular Biology of RNA 1995-96 Richard J. Roberts* University of California, Santa Cruz 1996-97 Ronald M. Evans Santa Cruz, California 1998-99 Elizabeth H. Blackburn 1999-2000 Carl R. Woese and Norman R. Pace 2000-01 Willem P. C. Stemmer and Ronald W. Davis 2001-02 Janos K. Lanyi and Sir John E. Walker* 12:00 noon 2002-03 Peter B. -

Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA

GENE SILENCING BY DOUBLE STRANDED RNA Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2006 by Andrew Z. Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA. I would like to thank the Nobel Assembly of the Karolinska Institutet for the opportunity to describe some recent work on RNA-triggered gene silencing. First a few disclaimers, however. Telling the full story of gene silencing would be a mammoth enterprise that would take me many years to write and would take you well into the night to read. So we’ll need to abbreviate the story more than a little. Second (and as you will see) we are only in the dawn of our knowledge; so consider the following to be primer... the best we could do as of December 8th, 2006. And third, please understand that the story that I am telling represents the work of several generations of biologists, chemists, and many shades in between. I’m pleased and proud that work from my labo- ratory has contributed to the field, and that this has led to my being chosen as one of the messengers to relay the story in this forum. At the same time, I hope that there will be no confusion of equating our modest contributions with those of the much grander RNAi enterprise. DOUBLE STRANDED RNA AS A BIOLOGICAL ALARM SIGNAL These disclaimers in hand, the story can now start with a biography of the first main character. Double stranded RNA is probably as old (or almost as old) as life on earth. -

T H I N K I N G F O Rwa

STANFORD UNIVERSITY 2005 ANNUAL REPORT THINK ING FORWARD THINKING FORWARD, ENROLLMENT (October 2005): by President John L. Hennessy 1 Undergraduate Students: 6,705 Graduate Students: 8,176 CAMPAIGN FOR UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION SURPASSES $1 BILLION GOAL 3 DEGREES AWARDED (2004-2005): Bachelor’s: 1,790 PURSUING MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH Master’s: 2,041 AND EDUCATION 6 Doctoral: 904 GRADUATE EDUCATION THE STANFORD PROFESSORIATE IS NEXT CHALLENGE 11 (October 2005): 1,771 STANFORD UNIVERSITY NOBEL LAUREATES: 15 RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS 12 PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS: 4 A WISE INVESTMENT, MACARTHUR FELLOWS: 23 by Board Chair Burton J. McMurtry 16 NATIONAL MEDAL OF SCIENCE RECIPIENTS: 21 2005 FINANCIAL REVIEW 17 NATIONAL MEDAL OF TECHNOLOGY RECIPIENTS: 3 REPORT FROM THE STANFORD AMERICAN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT COMPANY 55 ARTS AND SCIENCES MEMBERS: 224 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MEMBERS: 135 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING MEMBERS: 82 AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY MEMBERS: 41 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF EDUCATION MEMBERS: 26 WOLF FOUNDATION PRIZE WINNERS: 7 KORET FOUNDATION PRIZE WINNERS: 7 PRESIDENTIAL MEDAL OF FREEDOM RECIPIENTS: 3 On the cover: Lane History Corner is home to the Bill Lane Center for the Study of the North American West. The center is one of the university’s premier interdisciplinary centers, dedicated to facilitating interaction among a variety of disciplines to enrich scholarship on the West. The center was enhanced in 2005 with a $5 million gift from Bill Lane, matched with $4 million from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s gift to the School of Humanities and Sciences. Photo by Linda A. Cicero, Stanford News Service THINKING FORWARD A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT At my inauguration in the fall of 2000, I noted that throughout Stanford’s history the university has over- come challenges and created new possibilities when none previously existed. -

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C. Gunsalus 1912 Born in South Dakota, son of Irwin Clyde and Anna Shea Gunsalus 1935 B.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1937 M.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940 Ph.D. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940-44 Assistant Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1944-46 Associate Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1946-47 Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1947-50 Professor of Bacteriology, Indiana University 1949 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1950-55 Professor of Microbiology, University of Illinois 1955-82 Professor of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1955-66 Head of Division of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1959 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1959-60 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1962 Patent granted for lipoic acid 1965- Member of National Academy of Sciences 1968 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1972-76 Member Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1977-78 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1973-75 President of Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1978-81 Chairman of National Academy of Sciences, Section of Biochemistry 1982- Professor of Biochemistry, Emeritus, University of Illinois 1984 Honorary Doctorate, Indiana University 15/5/40 2 Box Contents List Box Contents Box Number Biographical and Personal Biographical Materials, 1967-1995 1 Personal Finances, 1961-65 1-2 Publications, Studies and Reports Journals and Reports, 1955-68 -

Francis Crick Personal Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1k40250c No online items Francis Crick Personal Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2007, 2016 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Francis Crick Personal Papers MSS 0660 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Francis Crick Personal Papers Creator: Crick, Francis Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0660 Physical Description: 14.6 Linear feet(32 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 2 oversize folders, 4 map case folders, and digital files) Physical Description: 2.04 Gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1935-2007 Abstract: Personal papers of British scientist and Nobel Prize winner Francis Harry Compton Crick, who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers document Crick's family, social and personal life from 1938 until his death in 2004, and include letters from friends and professional colleagues, family members and organizations. The papers also contain photographs of Crick and his circle; notebooks and numerous appointment books (1946-2004); writings of Crick and others; film and television projects; miscellaneous certificates and awards; materials relating to his wife, Odile Crick; and collected memorabilia. Scope and Content of Collection Personal papers of Francis Crick, the British molecular biologist, biophysicist, neuroscientist, and Nobel Prize winner who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers provide a glimpse of his social life and relationships with family, friends and colleagues. -

Lasker Interactive Research Nom'18.Indd

THE 2018 LASKER MEDICAL RESEARCH AWARDS Nomination Packet albert and mary lasker foundation November 1, 2017 Greetings: On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination for the 2018 Lasker Medical Research Awards. Since 1945, the Lasker Awards have recognized the contributions of scientists, physicians, and public citizens who have made major advances in the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, cure, and prevention of disease. The Medical Research Awards will be offered in three categories in 2018: Basic Research, Clinical Research, and Special Achievement. The Lasker Foundation seeks nominations of outstanding scientists; nominations of women and minorities are encouraged. Nominations that have been made in previous years are not automatically reconsidered. Please see the Nomination Requirements section of this booklet for instructions on updating and resubmitting a nomination. The Foundation accepts electronic submissions. For information on submitting an electronic nomination, please visit www.laskerfoundation.org. Lasker Awards often presage future recognition of the Nobel committee, and they have become known popularly as “America’s Nobels.” Eighty-seven Lasker laureates have received the Nobel Prize, including 40 in the last three decades. Additional information on the Awards Program and on Lasker laureates can be found on our website, www.laskerfoundation.org. A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored with Lasker Medical Research Awards. The 2018 Awards will -

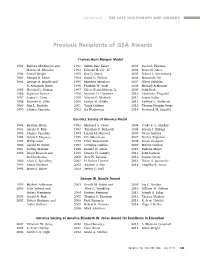

Previous Recipients of GSA Awards

GENETICS | THE 2015 GSA HONORS AND AWARDS Previous Recipients of GSA Awards Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal 1981 Barbara McClintock and 1991 Armin Dale Kaiser 2003 David S. Hogness Marcus M. Rhoades 1992 Edward H. Coe, Jr. 2004 Bruce N. Ames 1982 Sewall Wright 1993 Ray D. Owen 2005 Robert L. Metzenberg 1983 Edward B. Lewis 1994 David D. Perkins 2006 Masatoshi Nei 1984 George W. Beadle and 1995 Matthew Meselson 2007 Oliver Smithies R. Alexander Brink 1996 Franklin W. Stahl 2008 Michael Ashburner 1985 Herschel L. Roman 1997 Oliver Evans Nelson, Jr. 2009 John Roth 1986 Seymour Benzer 1998 Norman H. Horowitz 2010 Alexander Tzagoloff 1987 James F. Crow 1999 Salome G. Waelsch 2011 James Haber 1988 Norman H. Giles 2000 Evelyn M. Witkin 2012 Kathryn V. Anderson 1989 Dan L. Lindsley 2001 Yasuji Oshima 2013 Thomas Douglas Petes 1990 Charles Yanofsky 2002 Ira Herskowitz 2014 Frederick M. Ausubel Genetics Society of America Medal 1981 Beatrice Mintz 1992 Maynard V. Olson 2004 Trudy F. C. Mackay 1982 Gerald R. Fink 1993 Jonathan R. Beckwith 2005 Steven J. Elledge 1983 Charles Yanofsky 1994 Leland H. Hartwell 2006 Victor Ambros 1984 David S. Hogness 1995 Eric Wieschaus 2007 Shirley Tilghman 1985 Philip Leder 1996 Elliot Meyerowitz 2008 Susan Lindquist 1986 Gerald M. Rubin 1997 Christine Guthrie 2009 Marian Carlson 1987 Sydney Brenner 1998 Ronald W. Davis 2010 Barbara Meyer 1988 David Botstein and 1999 Charles H. Langley 2011 John Carlson Ira Herskowitz 2000 Jack W. Szostak 2012 Joanne Chory 1989 Allan C. Spradling 2001 H. Robert Horvitz 2013 Elaine A. Ostrander 1990 Nancy Kleckner 2002 Andrew Z. -

Discovery of the Secrets of Life Timeline

Discovery of the Secrets of Life Timeline: A Chronological Selection of Discoveries, Publications and Historical Notes Pertaining to the Development of Molecular Biology. Copyright 2010 Jeremy M. Norman. Date Discovery or Publication References Crystals of plant and animal products do not typically occur naturally. F. Lesk, Protein L. Hünefeld accidentally observes the first protein crystals— those of Structure, 36;Tanford 1840 hemoglobin—in a sample of dried menstrual blood pressed between glass & Reynolds, Nature’s plates. Hunefeld, Der Chemismus in der thierischen Organisation, Robots, 22.; Judson, Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1840, 158-63. 489 In his dissertation Louis Pasteur begins a series of “investigations into the relation between optical activity, crystalline structure, and chemical composition in organic compounds, particularly tartaric and paratartaric acids. This work focused attention on the relationship between optical activity and life, and provided much inspiration and several of the most 1847 HFN 1652; Lesk 36 important techniques for an entirely new approach to the study of chemical structure and composition. In essence, Pasteur opened the way to a consideration of the disposition of atoms in space.” (DSB) Pasteur, Thèses de Physique et de Chimie, Presentées à la Faculté des Sciences de Paris. Paris: Bachelier, 1847. Otto Funcke (1828-1879) publishes illustrations of crystalline 1853 hemoglobin of horse, humans and other species in his Atlas der G-M 684 physiologischen Chemie, Leizpig: W. Englemann, 1853. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace publish the first exposition of the theory of natural selection. Darwin and Wallace, “On the Tendency of 1858 Species to Form Varieties, and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and G-M 219 Species by Natural Means of Selection,” J. -

The Myth of Junk DNA

The Myth of Junk DNA JoATN h A N W ells s eattle Discovery Institute Press 2011 Description According to a number of leading proponents of Darwin’s theory, “junk DNA”—the non-protein coding portion of DNA—provides decisive evidence for Darwinian evolution and against intelligent design, since an intelligent designer would presumably not have filled our genome with so much garbage. But in this provocative book, biologist Jonathan Wells exposes the claim that most of the genome is little more than junk as an anti-scientific myth that ignores the evidence, impedes research, and is based more on theological speculation than good science. Copyright Notice Copyright © 2011 by Jonathan Wells. All Rights Reserved. Publisher’s Note This book is part of a series published by the Center for Science & Culture at Discovery Institute in Seattle. Previous books include The Deniable Darwin by David Berlinski, In the Beginning and Other Essays on Intelligent Design by Granville Sewell, God and Evolution: Protestants, Catholics, and Jews Explore Darwin’s Challenge to Faith, edited by Jay Richards, and Darwin’s Conservatives: The Misguided Questby John G. West. Library Cataloging Data The Myth of Junk DNA by Jonathan Wells (1942– ) Illustrations by Ray Braun 174 pages, 6 x 9 x 0.4 inches & 0.6 lb, 229 x 152 x 10 mm. & 0.26 kg Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925471 BISAC: SCI029000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Genetics & Genomics BISAC: SCI027000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Evolution ISBN-13: 978-1-9365990-0-4 (paperback) Publisher Information Discovery Institute Press, 208 Columbia Street, Seattle, WA 98104 Internet: http://www.discoveryinstitutepress.com/ Published in the United States of America on acid-free paper. -

Reproduction, Symbiosis, and the Eukaryotic Cell

Reproduction, symbiosis, and the eukaryotic cell Peter Godfrey-Smith1 Philosophy Program, City University of New York Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016; and History and Philosophy of Science Unit, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Edited by W. Ford Doolittle, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, and approved March 27, 2015 (received for review December 30, 2014) This paper develops a conceptual framework for addressing because the pattern of inheritance and the distribution of fitness questions about reproduction, individuality, and the units of differences may cancel, yielding no net change across genera- selection in symbiotic associations, with special attention to the tions (10, 11), but it still is a lucid summary of how Darwinian origin of the eukaryotic cell. Three kinds of reproduction are evolution works. As Lewontin emphasized, many different kinds distinguished, and a possible evolutionary sequence giving rise to of objects—including genes, organelles, cells, demes, and other a mitochondrion-containing eukaryotic cell from an endosymbiotic social groups—can satisfy Darwin’s scheme. All can form pop- partnership is analyzed as a series of transitions between each of ulations of units with variation, heritability, and fitness differ- the three forms of reproduction. The sequence of changes seen in ences. However, this use of the concepts of heritability and fitness this “egalitarian” evolutionary transition is compared with those takes for granted the idea of reproduction and especially the ex- that apply in “fraternal” transitions, such as the evolution of multi- istence of parent–offspring lineages between members of a pop- cellularity in animals. ulation.