Returnees in Syria Sustainable Reintegration and Durable Solutions, Or a Return to Displacement?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

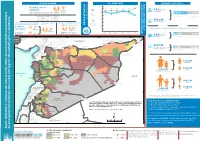

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

The Syrian Crisis: an Analysis of Neighboring Countries' Stances

POLICY ANALYSIS The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Series: Policy Analysis Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. ____________________________ The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non-Arab researchers. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies PO Box 10277 Street No. 826, Zone 66 Doha, Qatar Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651 www.dohainstitute.org Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Lebanese Position toward the Syrian Revolution 1 Factors behind the Lebanese stances 8 Internationally 14 Domestically 14 The Jordanian Stance 15 Regional and International Influences 18 The Syrian Revolution and the Arab Levant 22 NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES’ STANCES ON SYRIA Introduction The Arab Levant region has significant geopolitical importance in the global political map, particularly because of its diverse ethnic and religious identities and the complexity of its social and political structures. -

Field Developments in Idleb 51019

Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 Aleppo Countrysides During March and April 2019 the Information Management Unit 1 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 The Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) aims to strengthen the decision-making capacity of aid actors responding to the Syrian crisis. This is done through collecting, analyzing and sharing information on the humanitarian situation in Syria. To this end, the Assistance Coordination Unit through the Information Management Unit established a wide net- work of enumerators who have been recruited depending on specific criteria such as education level, association with information sources and ability to work and communicate under various conditions. IMU collects data that is difficult to reach by other active international aid actors, and pub- lishes different types of information products such as Need Assessments, Thematic Reports, Maps, Flash Reports, and Interactive Reports. 2 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 During March and April 2019 3 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 01. The Most Prominent Shelling Operations During March and April 2019, the Syrian regime and its Russian ally shelled Idleb Governorate and its adjacent countrysides of Aleppo and Hama governorates, with hundreds of air strikes, and artillery and missile shells. The regime bombed 14 medical points, including hospitals and dispensaries; five schools, including a kinder- garten; four camps for IDPs; three bakeries and two centers for civil defense, in addition to more than a dozen of shells that targeted the Civil Defense volunteers during the evacuation of the injured and the victims. -

Aleppo Governorate

Suruc ﺳورودج Oguzeli d أوﻏوﻠﯾزﯾﮫ d Şanlıurfa أوﻓﺔر DOWNLOAD MAP ZobarZorabi - C1948 اﻟﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ اﻟﺴــﻮرﻳﺔ SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Estiqama زوﺑﺎر _زوراﺑﻲ - BabnBoban d C1975 C1966 d AinAlArab اﻻﻘﻣﺳﺎﺔﺗﻛ_ورﺑﺎ d C1946 ﺑﺎﺑﺎن _ﺑوﺑﺎن OrubaKor - Ali d ﻌﻟﻋرﯾ انب -Musabeyli Susan Sus C1956 MorshedMorshed Binar d d Reference Map C1980 Minasﻣوﺳﻠﺎﯾﺑﯾﮫ BijanTramk ﻋروﺑﺔﻛﻠ_ﻲو ﻋر ALEPPO GOVERNORATE d C1987 d C6340 Sharan ﺻو ص _ﺻوﺻﺎن C1961 ﻣرﻣ ﺷردﻧ ﺷﺑﺎدﯾر d - C1940 NafKarabnafKarab ﻧﺎﻣﯾس UpperQurran d Scan it! Navigate! d ﺑﯾﺟﺎن _ﺗﻣرك BigDuwara Jraqli - Qola d C1988 ﺷران with QR reader App with Avenza PDF C2021 d C1998 d Gh arib ﻧﺎﻛ رف بﻛ_ﻧرﺎﺑف C1990 AziziyehMom - anAzu Kalmad FirazdaqArsalan - Tash ﻗﻧﻲﻗﻓرﺎاو ن Maps App ﺧﺮﻳــﻄﺔ ﻣﺮﺟــﻌﻴﺔ d TalHajib d C6341 C1943 ﻗوﻻ ﻟداوﻛاﻟﺑﯾ راةرة _ﻠﻲﺟﺎﻗر Gaziantep d d d C1974 C1954 ﻣﺤــــﺎﻓـﻈـﺔ ﺣﻠﺐ ﻏرﯾ ب d C1949 d ﻣﻠدﻛ ﺗ لﺣﺎ ﺟ بd ﻔﻟرزادق_أرﺳﻼ طﺎن ش d ﻋزﯾزﯾﺔﻣ_ﻣوﺎ ﻋنزو Polateli Jebnet Shakriyeh- UpperJbeilehQorrat - Quri d KharabNas Karkamis C1995 d Mashko C1972 ﺑوﻠﻻﯾﺗﯾﮫ -QantarraQantaret Kikan ﻏﺎﻧﺗز ﺎﻋيب d s C1994 d Qarruf YadiHbabQawi - KorbinarNabaa - BigEin Elbat C1967ﺟlu/ﻠabرا aJrﺑس C1936 ﻧﻲﻗﻗﻓﻗﺎوو ﻠ_رﺟﺑﺔةرﯾي ﻧﺟﺔﺑ ﻛﺎﻛﻣرﺎﯾ س ﺧرﻧاﺎ بس d C1985 C1976 C1962 C1957 ﻟﺷاﻛﺎرﯾﺔﻣ_ﻛﺷو d d ﻧطﻘﻧرطﻟﻛةﻛﻗ ﯾﺎرا_ةن KherbetAtu d ﻛﺎ isﻛﻣ/رﺎﯾ amسKark ﻛ ﻟﻋﺑﯾﺑﯾ طانر KharanKort ﻧﻌﺑﺔﻟﻛ_اورﻧﺑﺎﯾر ﻟﺣاﺑﺎ ب ﯾﻗ_دو يي ﻗروف Jarablus Shankal ] C2001 d d d JilJilak d MeidanEkbis Kusan C2227 ShehamaBandar - C1968 C1482 d C2012 C1964 ﺧر ﺑﻋطﺔو C1488 C1490d d ﺧراﻛ وبرت d UpperDar Elbaz BigMazraet Sofi ﺟﻠراﺑس - HjeilehJrables ﺟﯾل _ﻠكﺟﯾ MaydanKork - Kitan -

Epidemiological Findings of Major Chemical Attacks in the Syrian War Are Consistent with Civilian Targeting: a Short Report Jose M

Rodriguez-Llanes et al. Conflict and Health (2018) 12:16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0150-4 SHORTREPORT Open Access Epidemiological findings of major chemical attacks in the Syrian war are consistent with civilian targeting: a short report Jose M. Rodriguez-Llanes1, Debarati Guha-Sapir2 , Benjamin-Samuel Schlüter2 and Madelyn Hsiao-Rei Hicks3* Abstract Evidence of use of toxic gas chemical weapons in the Syrian war has been reported by governmental and non-governmental international organizations since the war started in March 2011. To date, the profiles of victims of the largest chemical attacks in Syria remain unknown. In this study, we used descriptive epidemiological analysis to describe demographic characteristics of victims of the largest chemical weapons attacks in the Syrian war. We analysed conflict-related, direct deaths from chemical weapons recorded in non-government-controlled areas by the Violation Documentation Center, occurring from March 18, 2011 to April 10, 2017, with complete information on the victim’s date and place of death, cause and demographic group. ‘Major’ chemical weapons events were defined as events causing ten or more direct deaths. As of April 10, 2017, a total of 1206 direct deaths meeting inclusion criteria were recorded in the dataset from all chemical weapons attacks regardless of size. Five major chemical weapons attacks caused 1084 of these documented deaths. Civilians comprised the majority (n = 1058, 97.6%) of direct deaths from major chemical weapons attacks in Syria and combatants comprised a minority of 2.4% (n = 26). In the first three major chemical weapons attacks, which occurred in 2013, children comprised 13%–14% of direct deaths, ranging in numbers from 2 deaths among 14 to 117 deaths among 923. -

G Secto R Objective 1: Improve the Fo Od Security Status of Assessed Foo D Insecure Peo Ple by Emergency Humanita

PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE IN NEED SO1 RESPONSE JANUARY 2017 CYCLE 8 7m Food & Livelihood 9 7 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m million Assistance Million 5.01 ORIGIN Food Basket 6 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 SO1 6.16m 3.35 M 1.631.79 MM 5.96m 5.8m 5.89m 3.35m 1.63m Target 5.45m 5 From within Syria From neighbouring September 2015 8.7 Million 5.01m countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA 4 September 2016 9.0 Million 459,299 Cash and Voucher 3 LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING OVERALL TARGET JAN 2017 PLAN RESPONSE Reached FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher BENEFICIARIES Beneficiaries Food Basket, 2 Cash & Voucher - 7 Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided 5.01 1 life sustaining MODALITIES AND Million 9 Million Million 0 Emergency 2 (72%) of SO1 Target AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC JAN BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY Response Million 291,911 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.08million 1.79 M 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E From within Syria From neighbouring Bread-Flour countries 7 Cizre- 1 g! 0 Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 2 T U R K E Y Darbasiyah Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y g! g! g! Ayn al Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa 635,144 g! g! Akcakale-Tall g! Bab As Abiad g! Emergency Response with 11,700 580,838 Salama Cobanbey g! Ready to Eat Ration From within Syria From neighbouring g! g! countries Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H Bab al Hawa g! N A L E P P O " A L E P P O 0 Karbeyaz ' 0 Yayladagi ° g! A R - R A Q Q A 6 g! A R - R A Q Q A 3 1,193,251 Women IID L E B L A T T A K IIA 1,374,537 2,567,787 Girls Female Beneciaries H A M A Mediterranean D E II R -- E Z -- Z O R Sea T A R T O U S II R A Q T A R T O U S Al Arida g! 1,081,796 Abu Men H O M S Kamal-Khutaylah H O M S g! 1,360,733 L E B A N O N 2,442,530 Boys N " Male Beneciaries 0 ' 0 ° 4 3 Masnaa-Jdeidet Yabous *Note: SADD is based on ratio of 49:51 for male/female due to lack of consistent data across UNDOF g! partners.