Download Pilgrimage in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward Turf labyrinths, or ‘turf mazes’ as they are popularly known in Britain, were once found throughout the British Isles (including a few examples in Wales, Scotland and Ireland), the old Germanic Empire (including modern Poland and the Czech Republic), Denmark (if the frequently encountered Trojaborg place-names are a reliable indicator) and southern Sweden. They are formed by cutting away the ground surface to leave turf ridges and shallow trenches, the convoluted pattern of which produces a single pathway, which leads to the centre of the design. Most were between 30 and 60 feet (9-18 metres) in diameter and usually circular, although square and other polygonal examples are known. The designs employed are a curious mixture of ancient classical types, found throughout the region, and the medieval types, found principally in England. Folklore and the scant contemporary records that survive suggest that they were once a popular feature of village fairs and other festivities. Many are found on village greens or commons, often near churches, but sometimes they are sited on hilltops and at other remote locations. By nature of their living medium, they soon become overgrown and lost if regular repair and re-cutting is not carried out, and in many towns and villages this was performed at regular intervals, often in connection with fairs or religious festivals. 50 or so examples are documented, and several hundred sites have been postulated from place-name evidence, but only eleven historic examples survive – eight in England and three in Germany – although recent replicas of former examples, at nearby locations, have been created at Kaufbeuren in Germany (2002) and Comberton in England (2007) for example. -

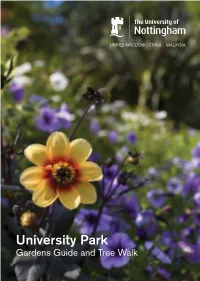

University Park Gardens Guide and Tree Walk

University Park Gardens Guide and Tree Walk 1 We are proud of the those from Nottingham Welcome University’s landscaped and East Midlands in campuses and visitors Bloom, the local and 4 Horticultural highlights are welcome to enjoy our National Civic Trust and 9 Millennium Garden gardens, walks and trees. the British Association of 12 Lakeside Walk Landscape Industries. University Park has 14 Tree Walk The Friends of University been awarded a Green Please use this guide 16 University Park map Flag every year since to explore and enjoy Park encourage everyone to 22 Our other campuses enjoy the campus grounds and 2003. We were the first University Park. all are welcome at their events. 24 Green issues University to achieve this. w: nott.ac.uk/friends 31 Tree Walk map Other awards include 2 3 Horticultural highlights University Park is very much in the English landscape style, with rolling grassland, many trees, shrubs and water features. An adjoining lake divides it from Highfields Park, which is managed by Nottingham City Council. Formal displays In the summer the display beds are vibrant with exotic annuals One of our boldest displays and bedding plants. In spring is at the North Entrance they are awash with colour from beside the A52 roundabout. A biennials and spring bulbs. contemporary arrangement of informal beds for annual bedding A second, smaller area of formal is backed by a border of exotic bedding is at the West Entrance shrubs, bamboos and grasses, by the old lodges. In the summer, which add value in winter. These large pots of brilliant bedding are complemented by boulders plants enhance our involvement and areas of cobbles. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Job 134675 Type

Superb village house with leisure facilities Oak Tree Farm, The Green, Hilton, Huntingdon, PE28 9NB Freehold Five bedrooms • Useful outbuildings, garaging • Guest annexe/office • Beautiful, mature private gardens • Swimming pool • Floodlit astroturf tennis court with practice wall • In all 0.68 acres Local information contemporary and traditional • Oak Tree Farm fronts the 27 fittings. Listed Grade II and acre common know as “The originally a 15th century hall Green” in the attractive village of house with a later 17th century Hilton, close to the village hall, cross wing and first floor which turf maze and cricket pavilion. was added at a similar time. Constructed of timber frame, the • St Ives (4.5 miles) is a market exterior walls are now town on the river Ouse, well predominantly brick under a reed served for local shopping thatched roof. In the same including a Waitrose supermarket ownership for the last 40 years, and numerous restaurants. the property has been sensitively upgraded and now provides • For the Cambridge commuter extensive, characterful there is access to the A14 which accommodation, useful is in the process of being outbuildings, swimming pool and considerably upgraded. The tennis court together with a Guided Busway from St Ives beautiful mature and well provides services into the maintained cottage garden. Science Park, Cambridge station and Addenbrookes. Period features include exposed timbers, Inglenook fireplaces, • The A14 leads south to vaulted bedrooms and an Cambridge, the M11 and M25; intriguing very early door north to Huntingdon, the A1, M1 & (thought to be 15th century) M6. which provides access to the shower room. -

Mazes and Labyrinths

Mazes and Labyrinths Author: W. H. Matthews The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mazes and Labyrinths, by W. H. Matthews This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Mazes and Labyrinths A General Account of their History and Development Author: W. H. Matthews Release Date: July 9, 2014 [EBook #46238] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAZES AND LABYRINTHS *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net MAZES AND LABYRINTHS [Illustration: [_Photo: G. F. Green_ Fig. 86. Maze at Hatfield House, Herts. (_see page 115_)] MAZES AND LABYRINTHS A GENERAL ACCOUNT OF THEIR HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENTS BY W. H. MATTHEWS, B.Sc. _WITH ILLUSTRATIONS_ LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. 4 NEW YORK, TORONTO BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS 1922 _All rights reserved_ _Made in Great Britain_ To ZETA whose innocent prattlings on the summer sands of Sussex inspired its conception this book is most affectionately dedicated PREFACE Advantages out of all proportion to the importance of the immediate aim in view are apt to accrue whenever an honest endeavour is made to find an answer to one of those awkward questions which are constantly arising from the natural working of a child's mind. It was an endeavour of this kind which formed the nucleus of the inquiries resulting in the following little essay. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

Things to See and Do

Things to See and Do Historic Places Name Location Distance Telephone Facilities Belton House Grantham 26.7 01476 566116 Belton House is a Grade I listed country house. The mansion is surrounded by formal gardens NG32 2LW miles and a series of avenues leading to follies within a larger wooded park. Tours of the house, gardens and parkland. Large adventure playground. OPEN: Wed-Sun 12.30pm-5pm Belvoir Castle – Grantham 28 miles 01476 871001 One of the finest examples of Regency architecture in the world. Tours of the state rooms, Engine Yard NG32 1PE formal gardens and woodland trails. Visit the Engine Yard, home to artisan boutiques, a spa, the Balloon Gin Bar, Fuel Tank restaurant and the Duchess Gallery. OPEN: Mon-Sun 10am-5.30pm. CLOSED: Friday Browne’s Hospital Stamford 0.7 miles 01780 481834 Almshouses built in 1474, original furniture and stained glass. Call to book a guided tour, cost and Museum PE9 1PF £3.50 per head. OPEN: For pre-booked tours only Burghley House & Stamford 1.3 miles 01780 752451 One of the most impressive Elizabethan houses in England, with eighteen treasure-filled state Gardens PE9 3JY rooms boasting a world-renowned collection of tapestries, porcelain and paintings. Sculpture garden, garden of surprises and deer park. Burghley Horse trials takes place every September. OPEN: March to October Flag Fen Peterborough 18.5 01733 864468 Flag Fen Archaeology Park is home to a kilometre-long wooden causeway and platform Archaeology Park PE6 7QJ miles perfectly preserved in the wetland. 3300 years ago, this was built and used by the Prehistoric fen people as a place of worship and ritual. -

Saffron Walden Mazes Records Show That by 1905 the Maze Was Open to the Public

Swan Meadow Maze The Saffron The town’s most recent Walden Mazes open-air maze was opened in August 2016 by world expert Jeff Saward to mark the beginning of the third Saffron Walden Maze Festival and, appropriately for a gateway to the town’s historic attractions, its internal layout announces that ‘Saffron Walden Amazes’. The use of reconstituted stone paving for the walkways, dark blue slate pieces to infill the subdivisions, woven willow for the fence enclosure and external ground cover The Jubilee Garden Labyrinth planting of pachysandra and miniature daffodils is intended to complement the natural surroundings of It was always the hope of the Saffron Walden Initiative willow trees and the nearby duck pond. committee members, who organised the second Saffron Miniature finger labyrinths and mazes are set into the Walden Maze Festival in 2013, that they would be able to tops of pre-cast planters featuring a Greek key design leave a permanent and tangible addition to the unique and provide the opportunity of added interaction for presence of two historic mazes in the town. After young children as they move around the turns of the investigating three other sites which proved maze’s pathways. There are two entry/exit points from incompatible with ancient monument restrictions or the adjacent public footpath, each of which link to the local authority plans for recreation, the centrally located north-east corner where a large angular head overlooks Jubilee Garden bandstand was proposed and approved the whole installation. by the Town Council. The form of the octagonal covered space suggested a Michael Ayrton’s Sun Maze Sculpture labyrinth made out of contrasting paving blocks laid over the existing concrete slab, which will permit its in The Fry Art Gallery continued use for music performances and art exhibitions. -

BATTISFORD & DISTRICT GARDENING CLUB 2019 50Th

BATTISFORD & DISTRICT GARDENING CLUB 2019 50th Issue of Newsletter! 6th July 2019, 12th Annual Gardening Club Show The Combs and Battisford Fete took place on Battisford Village Green for the first time. This of course meant a new venue for the BDGC Gardening Show, and a new smaller marquee—see above. Monday 13th May Monday 3rd June Visit to Otley Hall Gardens Visit to Moat House, On a fine May evening 35 members and guests assembled at Little Saxham the historic Otley Hall for a guided tour with Head gardener Simon Nickson and Guide Andy Vince. The history and creation of the gardens, canal, knot garden, mosaic, mound A lovely June evening saw us at NGS Moat House, Saxham and maze were all explained with enthusiasm. We were near Bury St. Ed’s. Richard Mason gave us a brief history of accompanied at times by a white peacock and his fan tailed the site and house, part of the Saxham Hall estate dating friend gave a fine display for us on the turf maze. A very back to 1507 with facts of cost in those far-off days such as enjoyable evening. Bill 8 days work for 2/- (Two Shillings = 10p) and bricks were 4p a 100, hand made too ! . Richard then handed us over to his wife Susan for the garden details, who between them have Otley Hall is a grade 1 listed 15th Century moated house created this lovely interesting garden of two acres in the with 10 acres of gardens. The current gardens are more re- past 20 years. -

A Witch Alone by Marian Green

A Witch Alone By Marian Green A Practical Handbook Thirteen Moons To Master Natural Magic. Book Cover (Front) (Back) Scan / Edit Notes Dedication Invocation Song Of The All-Mother Lord Of The Wildwood The Paradoxical Goddess Introduction 1 - A New Moon and a New Dream 2 - Meeting the Goddess and God of the Witches 3 - The Sacred Cycles 4 - A Circle Between the Worlds 5 - The Journey to the Otherworld 6 - Seeking Out Pagan Traces 7 - Considering the Healing Arts 8 - The Old Crafts of Divination and Dowsing 9 - Plant Power 10 - Moon Magic and Solar Cycles 11 - Recovering the Ancient Wisdom 12 - Dedication to the Old Ways 13 - Completing the Circle Scan / Edit Notes Versions available and duly posted: Format: v1.0 (Text) Format: v1.0 (PDB - open format) Format: v1.5 (HTML) Format: v1.5 (PDF - no security) Format: v1.5 (PRC - for MobiPocket Reader - pictures included) Genera: Wiccan (Witchcraft) Extra's: Pictures Included (for all versions) Copyright: 1991 / 1995 First Scanned: 2002 Posted to: alt.binaries.e-book Note: 1. The Html, Text and Pdb versions are bundled together in one zip file. 2. The Pdf and Prc files are sent as single zips (and naturally don't have the file structure below) ~~~~ Structure: (Folder and Sub Folders) {Main Folder} - HTML Files | |- {Nav} - Navigation Files | |- {PDB} | |- {Pic} - Graphic files | |- {Text} - Text File -Salmun Dedication This book is dedicated to Ronald Hutton, who has done so much to unveil the mysteries of witchcraft to the 21st-century world Invocations Song Of The All-Mother I am the Mother Earth, and you are a child to me, Discover who you are and seek divinity. -

Hampton Court Palace Gardens, Estate and Landscape Conservation Management Plan 2011

Hampton Court Palace Gardens, Estate and Landscape Conservation Management Plan 2011 Contents Executive Summary 1 A. Introduction 3 Hampton Court Palace 3 This Conservation Management Plan (CMP) 3 Previous Gardens and Estates Plans 4 B. The Operating Context 5 Historic Royal Palaces 5 Our Cause 5 Our Principles 5 Our Strategy 6 Legislative and Planning Background 6 C. History and Significance of the Parks and Gardens 8 History of the Parks and Gardens 8 Significance 11 D. Current Operations 14 Progress and Developments since 2004 14 Partnerships 14 Gardens and Estates Research since 2004 15 Potential Future Research Directions 17 E. Our Policies 18 F. General Policies (Estate-Wide) 19 G. Treatment of the Character Areas 28 A Plan of Hampton Court Gardens and Estates divided into 16 Character Areas 29 1. Home Park and the Pavilion 30 1a. Home Park Meadows 37 2. Stud House and Stud Nursery 40 3. Hampton Court Road 44 4. The Walled Paddocks 47 5. The Arboretum and Twentieth Century Garden 49 6. The Great Fountain Garden 52 7. The Privy Garden 58 8 The Pond Garden 62 9. The Barge Walk 66 10. The West Front 71 11. The Tiltyard 75 12. The Wilderness 79 13. The Glasshouse Nursery 83 14. Hampton Court Green 86 15. The Palace Courtyards 89 H. Major Projects 94 Home Park Meadows Habitat Restoration Project 94 Little Banqueting House Terrace and the Banqueting House Gardens 95 Creation of Upper Car Park exit on Vrow Walk with associated landscaping 97 Redesign of the Twentieth Century Garden in partnership with KLC and the installation of a new bridge across the north canal 97 The ‘Magic Garden’ 98 The Kitchen Garden 98 Annexe A: The Gardens Strategy Group 100 Annexe B: Select Bibliography 102 Executive Summary History of the Estate The gardens, estate and landscape of Hampton Court Palace represent a unique historical and horticultural resource of international value. -

Things to Do

2020 / 2021 hambleton_ad_2016.qxp_hambleton.qxd 04/03/2016 11:29 Page 1 goldmark A warm welcome, fresh coffee and some Orange Street, Uppingham, LE15 9SQ great art, sculpture and ceramics are just 01572 821424 10 minutes from Hambleton Hall. goldmarkart.com 2 CONTENTS About this Booklet . 5 Index of Locations . 24 Hambleton Hall . 6 Index of Goods and Services . 25 Market Towns . 8 Shopping for Antiques and Works of Art . 27 Oakham • Stamford • Uppingham . 8 Ceramics, Oil Paintings, Watercolours and Sculpture . 27 Melton Mowbray • Market Harborough . 9 Modern Jewellery and Antiques . 27. Landscape and Villages . 10 Jewellery/Antiques . 30 Drives . 10 Home and Interiors . 32 Ely • Lincoln • Peterborough . 11 General Shopping and Services . 29 Southwell • Northampton . 12 Fashion Shopping . 29 Local Churches . 13 Architectural Materials . 33 Gastro Pubs / Restaurants . 13 Gardens . 34 Country Houses . 13 Upholstery and Curtains . 32 Belton House • Belvoir Castle . 14 Taxi Service . 35 Althorp House• Elton Hall . 15 Cars . 34 Woolsthorpe Manor • The Portland Collection and Harley Gallery . 16 Wine Merchants . 36 Gardens . 17 Bakery . 37 Burghley House • Boughton House . 18 “Fay Ce Que Voudras” . 38 Doddington Hall • Rockingham Castle . 19 Outdoor Activities . 20 Walks/Jogging • Sailing and Windsurfing . .20 Cycling • Golf . 21 Motorsport • Riding/Carriage Driving Fox Hunting • Shooting • Swimming . 22 Fishing • Birds • Hot Air Ballooning . 23 3 STEFA HART & CAROLINE FIELD HAMBLETON DECORATING Stefa has run a successful interior design business Apart from on-going projects at Hambleton Hall and for over twenty years, creating stylish, comfortable & Hart’s Nottingham, recent projects have included practical interiors. Caroline joined her 10 years ago. London clubs, houses in London, Scotland, Munich & St Moritz, as well as local country houses and barns.