To Shame Or to Hide? Print Media Reporting of Sexualised Hazing in Taiwanese And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In His Steps

In His Steps Charles Sheldon (1896) Section 1 Chapter One "For hereunto were ye called; because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, that ye should follow in his steps." It was Friday morning and the Rev. Henry Maxwell was trying to finish his Sunday morning sermon. He had been interrupted several times and was growing nervous as the morning wore away, and the sermon grew very slowly toward a satisfactory finish. "Mary," he called to his wife, as he went upstairs after the last interruption, "if any one comes after this, I wish you would say I am very busy and cannot come down unless it is something very important." "Yes, Henry. But I am going over to visit the kindergarten and you will have the house all to yourself." The minister went up into his study and shut the door. In a few minutes he heard his wife go out, and then everything was quiet. He settled himself at his desk with a sigh of relief and began to write. His text was from 1 Peter 2:21: "For hereunto were ye called; because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example that ye should follow his steps." He had emphasized in the first part of the sermon the Atonement as a personal sacrifice, calling attention to the fact of Jesus' suffering in various ways, in His life as well as in His death. He had then gone on to emphasize the Atonement from the side of example, giving illustrations from the life and teachings of Jesus to show how faith in the Christ helped to save men because of the pattern or character He displayed for their imitation. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson Marks the Offi Cial Unveiling Ceremony: Pages 5 and 6

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1509 FELIX 03.02.12 The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson marks the offi cial unveiling ceremony: Pages 5 and 6 Fewer COMMENT students ACADEMIC ANGER apply to university OVERJOURNALS Imperial suffers 0.1% THOUSANDS TO REFUSE WORK RELATED TO PUBLISHER Controversial decrease from 2011 OVER PROFIT-MAKING TACTICS material on drugs Alexander Karapetian to 2012 Page 12 Alex Nowbar PAGE 3 There has been a fall in university appli- cations for 2012 entry, Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) ARTS statistics have revealed. Referred to as a “headline drop of 7.4% in applicants” by UCAS Chief Executive Mary Curnock Cook, the newly published data includes all applications that met the 15 January equal-consideration deadline. Imperial College received 14,375 applications for 2012 entry, down from 14,397 for 2011, a 0.1% decrease. Increased fees appear to have taken a toll. Towards the end of 2011 preliminary fi gures had indicated a 12.9% drop in To Bee or not to Bee university applications in comparison to the same time last year. Less marked but in Soho still signifi cant, 7.4% fewer applications were received for this cycle. Consider- Page 18 ing applications from England UCAS describes the true fi gures: “In England application rates for 18 year olds have decreased by around one percentage point in 2012 compared to a trend of in- creases of around one per cent annually HANGMAN ...Continued on Page 3 TEDx COMES TO IMPERIAL: Hangman gets a renovation PAGE 4 Page 39 2 Friday 03 february 2012 FELIX HIGHLIGHTS What’s on PICK OF THE WEEK CLASSIFIEDS This week at ICU Cinema Fashion for men. -

Black Tie for Summer Ball SCIENCE Sit-Down Formal Dinner Back on the Menu for This Year’S Event

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1511 FELIX 17.02.12 The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 TALKING TO THE SABBATICALS As nominations open for this year’s Union elections, Felix talks to the current Sabbs to fi nd out what exactly they have been doing for you: Page 6 Black tie for Summer Ball SCIENCE Sit-down formal dinner back on the menu for this year’s event Matthew Colvin der to make the dinner viable, there will It is currently planned for one cash bar been approved by the Union’s Executive be a minimum attendance fi gure. If this to be located in each venue, but should Committee and a “Summer Ball Forum” In a paper brought to Imperial College fi gure is not reached by a yet-to-be con- the number of tickets sold approach will be organised to receive feedback Union Council last Monday (February fi rmed date, the dinner will be cancelled 1,500, a cashless system will be consid- from the student body. 13) Deputy President (Finance & Servic- and refunds will be provided to those af- ered. Speaking at the Council meeting, Mind-reading es) Michael Foster outlined plans for this fected. The fairground also makes a return, Foster confi rmed that this year’s Ball year’s Summer Ball, which will see the Though entertainment is also yet to be alongside fi reworks and the after-party would see “a return to the style of 2010 machines return of black-tie and a formal dinner. confi rmed, it is expected that acts will be (priced between £5 and £7), which will and earlier” while maintaining a “very The event, to be held one week later spread across the Queen’s Lawn Stage begin at 11pm in the Union building, fi n- conservative and low-risk budget”. -

Horace Grant Gay Erotic Fan Fiction by Smacko It Was the Day That Joey

Horace Grant Gay Erotic Fan Fiction By Smacko It was the day that Joey had always dreamed of. He was finally getting the chance to meet his favorite basketball player, Horace Grant of the Chicago Bulls. He was so excited to finally meet his idol. He was ushered into the dressing room by Phil Jackson. Phil told him that he was really going to enjoy finally meeting Horace and that Horace was one of his favorite players. As he brought Joey into the locker room, Joey noticed that many of the other Bulls players were on there way out and there was no sight of Horace. At first Joey was disappointed. Finally after the rest of the Bulls players had left, Phil told him that Horace should be out of the showers anytime and that he had to go to a meeting with the owner of the team, Jerry Kraus. Finally Horace emerged from the showers only wearing a towel. Joey ran over and said “Hey Horace, I am your biggest fan.” Horace chuckled and said “I have been looking forward to meeting you for some time.” Joey could see the outline of a large member underneath his towel. Horace hugged Joey close and Joey could feel his pulsing member quivering against him. He suddenly became more aroused than he had ever been before. The feeling of Horace’s member against him sent chills up his spine. As he backed away he shivered in delight. Horace said “I have a surprise that you are going to love.” He reached into his towel and pulled out a set of Rec Specs TM. -

Mm2 Asia Invests in RINGS.TV

mm2 Asia Ltd. Co. Reg. No.: 201424372N 1002 Jalan Bukit Merah #07-11 Singapore 159456 www.mm2asia.com Press Release mm2 Asia invests in RINGS.TV. mm2 Asia subscribes for 15% of RINGS.TV with a further Call Option to increase stake to 20%. The 20% is a slight variation to the proposed 30% previously announced to accommodate a 10% co-investment by SPH. Singapore, 3 March 2017 – mm2 Asia Ltd. (“mm2 Asia” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”), entered into a Share Subscription and Shareholders’ Agreement on 28 February 2017 with SPH Media Fund Pte Ltd (“SPH”) (a subsidiary of SPH Group), RINGS.TV Pte Ltd (“RINGS.TV”), and its holding company, Mozat Pte Ltd, whereby mm2 Asia and SPH Media Fund Pte Ltd will acquire 15% and 7.5% respectively, through the new issuance of shares by RINGS.TV for a consideration amount of approximately S$2.25 million and S$1.125 million respectively (the “Proposed Investment”). Both mm2 Asia and SPH shall have an additional option to subscribe for option shares and increase their stakes to a total of 20% and 10%, for an aggregate consideration amount of approximately S$3 million and S$1.5 million respectively. The option shall be valid for one year from the date of the Share Subscription and Shareholders’ Agreement. The agreement formalises the non-binding Memorandum of Understanding entered into between mm2 Asia, RINGS.TV and Mozat Pte Ltd, dated 17 October 2016, whereby mm2 Asia has indicated its intention to acquire up to a 30% stake in RINGS.TV. -

Introduction to Singapore Press Holdings

IntroductionIntroduction toto SingaporeSingapore PressPress HoldingsHoldings Updated on 19 March 2012 23 May 07 1 FrequentlyFrequently AskedAsked QuestionsQuestions Reference slide no. 1. Why is SPH so dominant in the Singapore media industry? 3 – 4 2. Who are the controlling shareholders of SPH and what is their 5 stake? 3. Newspaper circulation is falling globally. What is SPH doing 6 about declining circulation? 4. Is SPH’s newspaper business affected by the Internet and other 7 media? 5. What are the growth areas of the Group? Will SPH expand 8-13 overseas? 6. What is the Group’s property Strategy? 14-15 7. What other projects is SPH investing in? 16 8. What is SPH’s operating margin and is it sustainable? 17 9. What is SPH’s dividend policy? 18 2 AA LeadingLeading MediaMedia OrganisationOrganisation Newspapers Dominant Newspaper Broadcasting Publisher in Singapore Magazines Leading Magazine 2 radio stations and 20% Publisher in stake in free-to-air TV Singapore & Malaysia Events/Out- SPH New Media of-home News portals, Events and outdoor Online classifieds advertising Property Investments -Approx. S$1b of investible funds -Paragon including MobileOne (13.9%) -Clementi Mall (60%) & Starhub (0.8%) - OpenNet (25%) 3 DominantDominant NewspaperNewspaper PublisherPublisher inin SingaporeSingapore SPH has a spectrum of products including the 166-year-old English flagship daily, The Straits Times, and the 88-year-old Chinese daily, Lianhe Zaobao. SPH publishes 18 out of 19* newspapers in Singapore In Singapore, 74% of population above newspapers has 15 years old read one more than 50%^ of SPH’s news share of the media ad publications daily market * SPH also has a 40% stake in Today – a freesheet by MediaCorp 4 ^ Source: SPH SPHSPH ShareholdingShareholding . -

Hfcsunday BULLETIN V

- . ' ' "ir tu-it.v- ri.iii'iiTii..rcfc,iCHifln'Mt"ii' jiJ)- - - mmiTT" i wt ' W 'fWjyw 'HHMI'm '' ( ""' rj??jrJxxZJhz Steame; T?ble. We don't promise the eaith for a nickle, but I FromJr EVERY " TIME " - av if. n VI "-- TJ S your name or tho J tiP .. I 1.7(1 "V y 4vi ff i urirk mi V your product lr.uWMlMMl--. ' ll 3 F, ' A WUF V yon are recervinjr gooci nq Is VffL. , .'I TWnerlca Mam if, vfrtlslng strlko to liicVwJ&4J " . NLOCVAlftmodn. fl the numbe!ltfipfc'vho j? y PFor Victoria. - HfcSUNDAY- j 1.1 rs 'h will keep Undoing this . i .V BULLETIN Aorangl jjjiiit JC"VV r- 'h TTre Advisor -rrs" From Victor! ' "v (Ja.ftH5S3:aiiowcra . WE GIVE THE BEST NEWSPAPER Vol. I. No. 17. 12 PAGESHONOLULU. TBRUITOKY OF HAWAII, SUNDAY MAY 18, 190212 PAGES PllIOB 5 OUNT Miss Alice L. McCully TWO HONOLULU LADIES Pacific Hardwares , Makes Pretty Bride WALK 28 MILES Are the Champions WEDDING IN CENTRAL UNION CHURCH WIN GRAND TUG-OF-WA- R TOURNAMENT TO THE HALEIWA HOTEL Returning to Visit Her Old Home She Meets Pulled from Public Works Boys in Twenty-tw-o the Man of Her Choice in and Half Minutes Close Pull Francis W. Smith Walalua, 3:05 p. m. (Special on Maul. The plucky Indies Immedi- Kaena Point lies before him, or her In Wela-ka-Ha- os Second. telephone message to Sunday Bu- ately were ready to prove what thej this Instance, Including tho vast cane-fiel- d were lletin) Arrived safely at Wala-lue- . -

From Lust to Love : Gay Erotic Romance Ebook

FROM LUST TO LOVE : GAY EROTIC ROMANCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Hicks | 192 pages | 17 Jul 2014 | Bruno Gmuender Gmbh | 9783867877909 | English | Berlin, Germany From Lust to Love : Gay Erotic Romance PDF Book A third scene involves an onstage rape: unsimulated oral sex briefly shown as is the "d" of another actor. Good nudity of the two main characters, including an extended scene with rock star Fogi. Both are searching for very different things in life. Director-screenwriter Ektoras Lygizos gives us an astonishing picture of a poverty-stricken reality. He's an attractive young man and throughout the movie we see him in various stages of undress underwear, Speedo, covered frontal, frontal. R min Drama, Romance, Thriller. Here ya go for a review I found: In budding author Christopher Isherwood goes to Berlin at the invitation of his friend W. Unrated 95 min Comedy, Drama, Fantasy. Antarctica R min Drama, Romance 6. Another tale where an old man continues to hit on a very hot hustler in a bathhouse. Lithe and full of longing, a young Italian embraces his provocative drag persona in this short and sensual documentary. A teen boy has sex for the first time with his girlfriend. Here's another reviews: Lightfarms debut short movie brings an all-star cast from the adult industry and drops them into the mainstream movie world, providing real chemistry between the actors, with real tension and drama like none other. Has a fun ending. If you are gay and enjoy fantasy type stories filled with hot young male bods, this is for you. -

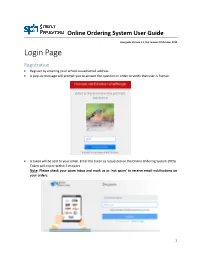

Login Page Registration Register by Entering Your School-Issued Email Address

Online Ordering System User Guide User guide Version 1.1, last revised: 22 October 2018 Login Page Registration Register by entering your school-issued email address. A pop-up message will prompt you to answer the question in order to verify that user is human. A token will be sent to your email. Enter the token as requested on the Online Ordering System (OOS). Token will expire within 5 minutes. Note: Please check your spam inbox and mark us as ‘not spam’ to receive email notifications on your orders. 1 Once token is successfully entered, user will be directed to the registration page to fill up details. Select your school and enter details – DID, Fax and Password. Password Requirements: o Exactly 8 alphanumeric characters o At least 1 lowercase o At least 1 uppercase o At least 1 number User will see the message below when they have successfully registered. 2 Login Users will be required to log in with their Email Address and Password. Reset Password If users forget their password, click “Forgot password” and enter your email address. A token code will be sent to your email. The token will expire within 5 minutes. User will then be prompted to enter their new password. 3 Dashboard My Dashboard Upon logging in, users are taken to the homepage – My Dashboard. Users can navigate using the tabs on the top right bar: On ‘My Dashboard’, users will be able to view the following: 1. Order Summary My Pending Orders: Users can save their orders as drafts and continue pending orders by clicking on the green arrow. -

Order of the Shadow Wolf Cyberzine

SoCiEtIeS ArCh NeMeSiS CyBeRpUnK E-ZiNe Issue #2 December 2014 welcome to the order of the... o o . o . o o o o o . o . ________ ___ ___ ________ ________ ________ ___ o __ |\ ____\|\ \|\ \|\ __ \|\ ___ \|\ __ \|\ \ |\ \ o \ \ \___|\ \ \\\ \ \ \|\ \ \ \_|\ \ \ \|\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \_____ \ \ __ \ \ __ \ \ \ \\ \ \ \\\ \ \ \ __\ \ \ . \|____|\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \_\\ \ \ \\\ \ \ \|\__\_\ \ ____\_\ \ \__\ \__\ \__\ \__\ \_______\ \_______\ \____________\ |\_________\|__|\|__|\|__|\|__|\|_______|\|_______|\|____________| . o \|_________| | | | . | . | | O . o | . o | O | /\ o /\ ___ O __ ________ ___ ________ . | \-------/ | . |\ \ |\ \|\ __ \|\ \ |\ _____\ / \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \|\ \ \ \ \ \ \__/ . | __ __ | . \ \ \ __\ \ \ \ \\\ \ \ \ \ \ __\ / \ \ \ \|\__\_\ \ \ \\\ \ \ \____\ \ \_| / \ . \ \____________\ \_______\ \_______\ \__\ / \ . \|____________|\|_______|\|_______|\|__| . / \ O | | . | / \ O . O . | . / \ /\ THE LAUNDRoMAT OF YOUR MIND /\ O O / \ /\ /\ EXTRA BIG DECEMBER ISSUE!!! / \ . / \/ \/ \ . /..\ < . / \ . / \ \ \ _\' /_ / . / \ . / \ \ \ . / . \ . / \ /________\___\___\ | . | /____ ___\ || || || \ . / || /\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\ ============================================================================== The Order OF THE SHADOW WOLF IS NOW IN COLOR!!!!! your online cyber-zine for: Occult home experiments - Synthesizers - Sorcery & Magick - DIY projects - Movies - Music - Counter Culture - UFOlogy - Poetry - Obsolete computers - Artificial Intelligence - Rastafarian Language -

Lucy Kirkwood

NSFW Lucy Kirkwood Characters CHARLOTIE, twenty-five RUPERT, twenty-eight SAM, twenty-four AIDAN, early forties MR BRADSHAW, late forties MIRANDA,late forties/early fifties Note on Text Aforward slash indicates interrupted speech. A comma on its own line indicates a beat; a silence shorter than a pause, or a shift in thought or rhythm. Thanks I would like to thank Simon Godwin, Dominic Cooke, Mel Kenyon and Ed Hime. There are also a number of people who generously gave of their time, knowledge and experience who do not want to be named, but they know who they are and I thank them too. L.K. This text went to press before the end of rehearsals and so may differ slightly from the play asperformed. 3 1. tors office of Doghouse The edi magazine, a weekly publication for young men. The magazines name appears in neon on the wall. Beyond the door, an open-plan office. There is a pool table, a fridge of drinks. A dartboard.T he editorsdesk has a desktop Apple computer on it. There are framed prints of topless photo shoots on the walls. A cricket bat in the corner. An enormous Liverpool FC flag strung fromthe ceiling. The pool table is strewn with toys and gadgets and computer games that the magazine has reviewed or is reviewing. CHARLOTIE, a middle-class girl from outside of London who now lives in Tooting, is sitting on a chair, a folder in her lap, furiously writing notes. She has other files on the floor which she consults fromtime to time.