An Interview with John Holmstrom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

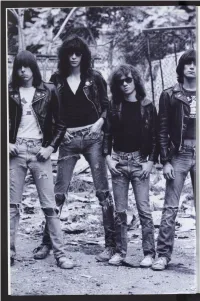

Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept

® The GRAMMY Museum and Delta Air Lines Present Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept. 16 Linda Ramone, Billy Idol, Seymour Stein, Shepard Fairey, And Monte A. Melnick To Appear At The Museum Opening Night For Special Evening Program LOS ANGELES (Aug. 24, 2016) — Following its debut at the Queens Museum in New York, on Sept. 16, 2016, the GRAMMY Museum® at L.A. LIVE and Delta Air Lines will present the second of the two-part traveling exhibit, Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk. On the evening of the launch, Linda Ramone; British pop/punk icon Billy Idol; Seymour Stein, Vice President of Warner Bros. Records and a co-founder of Sire Records, the label that signed the Ramones to their first record deal; artist Shepard Fairey; and Monte A. Melnick, longtime tour manager for the Ramones, will participate in an intimate program in the Clive Davis Theater at 7:30 p.m. titled "Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Celebrating 40 Years Of The Ramones." Tickets can be purchased at AXS.com beginning Thursday, Aug. 25 at 10:30 a.m. Co-curated by the GRAMMY Museum and the Queens Museum, in collaboration with Ramones Productions Inc., the exhibit commemorates the 40th anniversary of the release of the Ramones' 1976 self-titled debut album and contextualizes the band in the larger pantheon of music history and pop culture. On display through February 2017, the exhibit is organized under a sequence of themes — places, events, songs, and artists —and includes items by figures such as: Arturo Vega (who, along with the Ramones, -

Editorial MILENIO

Índice onomástico 10cc, 96, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 171 Alice Cooper, 82, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, Archiduque Luis Salvador de Aus- Bee Gees, 110 2 Chainz, 285 107 tria, 69 Ben Vaughn, 20 2D, 281 Alicia Keys, 287 Aretha Franklin, 23 Benjamin Disraeli, 33 A Certain Ratio, 258 Alien Lanier, 144 Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup, 13 Bernard Butler, 251, 252 A Tribe Called Quest, 285 All You Can Eat, 25 Artie Shaw, 23 Bernard Edwards, 191 Aaron Rapoport, 175, 179 Allan Clarke, 218 Arturo Vega, 147, 149, 150 Bernard Pierre Wolff, 185, 187, 188, Abba, 65 Allan Tannenbaum, 50 Athena Demos, 228 189 Abbie Rose, 203 Allen Ginsberg, 202 Athlete, 289 Bernard Shaw, 27 Acy R. Lehman, 24, 129 Alton Kelley, 52 Atomic Rooster, 62 Bernard Sumner, 275 Ad lnfinitum, 258 AM, 19 Atrocity, 195 Bernie Karlin, 129 Adam Again, 207 Amanda Lear, 115, 123 Aubrey Powell, 97, 99, 153, 170 Bernie Taupin, 109, 112 Augusto Rivalta, 187 Adam Clayton, 236, 238, 240 Amber Rose, 212 Beth Orton, 253 Ava Cherry, 115 Adam Faith, 115 Amy Winehouse, 105 Betty Blue, 242 Aelbert Cuyp, 199 Awesome Snakes, 84 Beverly, 268 Ana Johnson, 224 Ahmed Abdul Malik, 76 Axxe, 125 Beyoncé, 286 André C. Le Breton, 91 Aida Griffin, 54 B.P. Fallen, 127, 130 Big Audio Dynamite, 15 André Malraux, 69 MILENIO Al Green, 286 Bad Company, 278 Big Boi, 286 Andrew Boloton, 28 Al Stewart, 65 Baden-Powell, 216 Big Brother & the Holding Com- Andrew Loog Oldham, 37, 38, 40 Alain Delon, 215, 216, 219 Ban Ban Bazar, 25 pany, 42, 43, 53 Andy Fletcher, 201 Alan Erasmus, 186 Banana Splits, 279 Bill Graham, 43, 53 Andy Griffith, -

Smash Hits Volume 33

FORTNIGHTLY March 6-19 1980 i: fcMrstfjg i TH LYING LIZARDS .;! albums STS EDMUNDS )ur GRRk/£V£t/HlfLK HATES 7EEJM THAT TVf^ itav UGLYMONSTERS/ ^A \ / ^ / AAGHi. IF THERE'S ONE THING THATMAKES HULK REALLYAM6RY, IT'S PEOPLE WHO DON'T LOOK AFTER THEIRT€€TH! HULK GOES MAD UNLESS PEOPLE CLEAN THEIR TEETH THOROUGHLY EVERY DAY (ESPECIALLY LAST THING ATNIGHT). HE GOES SSRSfRK IFTHEY DON'T VISITTHE DENTIST REGULARLY! IF YOU D0N7 LOOKAFTER YOUR TEETH, SOMEBODY MAY COME BURSTING INTO YOUR HOUSE IN A TERRIBLE TEMPER AND IT WON'T BE THE MamAM...... 1 ! IF YOU WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FlU IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER P.O BOX 1, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK COlO 6SL. tAeE(PUASETICKTHEAPPROPRIATEBOir)UNDERI3\Z\i3-l7\3lSANDOVER\JOFFERCLOSESONAPRIL30THmO.AUOW2SDAYSFORDELIVERY(sioaMPmisniA5l}l SH 1 uNAME ADDRESS X. i ^i J4 > March 6-19 1980 Vol 2 No. 5 Phew! Talk about moving ANIMATION mountains — we must have The Skids 4 shifted about six Everests' worth of paper this fortnight, what with ALABAMA SONG your voting forms and Walt David Bowie 4 Jabsco entries. With a bit of luck we'll have the poll results ready SPACE ODDITY forthe next issue but you'll find David Bowie 5 our Jabsco winners on page 26 of this issue. There's also an CUBA incredibly generous Ska Gibson Brothers 8 competition on page 24, not to mention our BIG NEWS! Turn to ALL NIGHT LONG the inside back page and find out Rainbow 14 what we mean . I'VE DONE EVERYTHING FOR YOU Sammy Hagar 14 Managing Editor HOT DOG Nick Logan Shakin' Stevens 17 Editor HOLDIN' -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De La Psicodelia Al Genoveva Li

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965-1979 TESIS DOCTORAL Directores: Genoveva Linaza Vivanco Santiago Javier Ortega Mediavilla Doctorando Javier Fernández Páiz (c)2017 JAVIER FERNANDEZ PAIZ Relaciones entre arte y rock. Aspectos relevantes de la cultura rock con incidencia en lo visual. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965 - 1979 INDICE 1- INTRODUCCIÓN 1-1 Motivaciones y experiencia personal previa Pág. 5 1-2 Objetivos Pág. 6 1-3 Contenidos Pág. 8 2- CARACTERÍSTICAS ESTILÍSTICAS, TENDENCIAS Y BANDAS FUNDAMENTALES 2-1 ORÍGENES DEL ROCK 2-1-1 Características fundaMentales del rock priMitivo Pág. 11 2-1-2 La iMagen del rock priMitivo Pág. 15 2-1-2-1 El priMer look del Rock 2-1-2-2 El caudal de iMágenes del priMer Rock y el color 2-1-3 PriMeros iconos del Rock Pág. 17 2-2 BRITISH INVASION Pág. 22 2-3 MODS 2-3-1 Características principales Pág. 26 2-3-2 El carácter visual de la cultura Mod Pág. 29 2-4 PSICODELIA Y HIPPISMO 2-4-1 Características principales Pág. 32 2-4-2 El carácter visual de la Psicodelia y el Arte Psicodélico Pág. 42 2-5 GLAM 2-5-1 Características principales Pág. 55 2-5-2 El carácter visual del GlaM Pág. 59 2-6 ROCK PROGRESIVO 2-6-1 Características principales Pág. 65 2-6-2 El carácter visual del Rock Progresivo Pág. 66 2-7 PUNK 2-7-1Características principales Pág. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 1 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhatt

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village, CBGB was a bar and music venue which features prominently in the history of American punk rock, New Wave and Hardcore music genres. The club’s owner, Hilly Kristal, was always involved with music and musicians, having worked as a manager at the legendary jazz club Village Vanguard booking acts like Miles Davis. When CBGB first opened its doors in the early seventies the venue featured mostly country, blue grass, and blues acts (thus CBGB) before transitioning over to punk rock acts later in the decade. Many well know performers of the punk rock era received their start and earliest exposure at the club, including the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, and Joan Jett. During the New Wave era, performers like Elvis Costello, Talking Heads and even early performances from the Police graced the stage in the now legendary venue. Located at 315 Bowery, which is situated near the northern section of Bowery before it splits into 3rd and 4th Avenues at Cooper square, the original building on the site was constructed in 1878 and was used as a tenement house for 10 families with a shop (liquor store) on the ground floor. In 1934, 315 and 313 were combined into one building and the façade was redesigned and constructed in the Art Deco style, as documented in the 1940 tax photo. At that time, the building was occupied by the Palace Hotel with a ground floor saloon. -

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Samuel Schmid Fait Escale Au Locle

Pascal Couchepin KEYSTONE FOOTBALL Sion et Bâle se qualifient pour le 1er tour veut aider de la Coupe UEFA. Pas YB. >>> PAGE 20 les parents Le conseiller fédéral entend soutenir le système des bons de garde. >>> PAGE 26 KEYSTONE Vendredi 31 août 2007 ● www.limpartial.ch ● N0 39684 ● CHF 2.– / € 1.30 JETONS DE PRÉSENCE Volte-face de la BCN Samuel Schmid fait escale au Locle KEYSTONE Fin de la polémique suscitée par la hausse des indemnités des administrateurs de la Banque cantonale (présidée par le socialiste Jean-Pierre Ghelfi): le conseil fait marche arrière. >>> PAGE 5 POPULATION Une croissance due aux étrangers La Suisse comptait 7,5 millions d’habitants à la fin de l’année dernière, soit 50 000 de plus qu’à fin 2005. Cette hausse, dans la lignée de celles enregistrées depuis 2000, est avant tout due à l’immigration. Le phénomène est par ailleurs plus marqué dans les zones urbaines que dans les campagnes. >>> PAGE 25 RICHARD LEUENBERGER JOURNÉE DES VILLES Le conseiller fédéral Samuel Schmid a participé Palme d’or Curiosités hier à l’assemblée de l’Union des villes suisses, réunie jusqu’à aujourd’hui au Locle. Patrimoine Les Journées Cent cinquante délégués d’exécutifs ont fait le déplacement. >>> PAGE 6 européennes se tiendront FRENETIC les 8 et 9 septembre. Le bois est à l’honneur RADIO-TV MUSIQUE SP de cette 14e édition. Découvertes Lumières en perspective. >>> PAGE 3 La grosse colère jurassiennes du patron de RTN Hier à Delémont, le chef Grand film Couronné à de l’Orchestre symphonique Cannes, «4 mois, A la tête des stations RTN, rassien et qui pourrait entraî- du Jura, Facundo Agudin, a 3 semaines, 2 jours» est une DAVID MARCHON RJB et RFJ, le Jurassien ner un accroissement des présenté la saison de émouvante balade tragique Pierre Steulet estime qu’il ne émissions communes entre Musique des Lumières. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales).