An Essential Victorian Preview.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

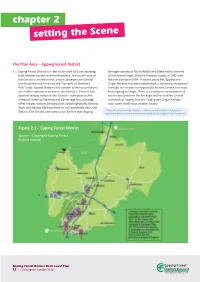

Chapter 2 Setting the Scene

chapter 2 setting the Scene The Plan Area – Epping Forest District 2.1 Epping Forest District is in the south-west of Essex abutting through stations at North Weald and Blake Hall to the end both Greater London and Hertfordshire. The south–west of of the line at Ongar. Blake Hall station closed in 1981 with the District is served by the London Underground Central the line closing in 1994. In recent years the ‘Epping and Line (both the main line and the ‘Hainault via Newbury Ongar Railway’ has been established, a nationally recognised Park’ loop). Epping Station is the eastern terminus and there heritage rail service running on this former Central Line track are 7 other stations in service in the District 1. There is one from Epping to Ongar. There is currently no operational rail national railway station in the District – at Roydon on the connection between the heritage rail line and the Central Liverpool Street to Stansted and Cambridge line, although Line track at Epping, but the ‘Epping and Ongar Railway’ other railway stations (Broxbourne, Sawbridgeworth, Harlow runs some shuttle bus services locally. Town and Harlow Mill) are close to, and accessible from, the 2 District. The Central Line used to run further than Epping, These are Theydon Bois, Debden, Loughton and Buckhurst Hill, together with the stations on the branch line at Roding Valley, Chigwell and Grange Hill Figure 2.1 – Epping Forest District Source – Copyright Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Draft Local Plan 12 | Consultation October 2016 2.2 The M25 runs east-west through the District, with a local road 2.6 By 2033, projections suggest the proportion of people aged interchange at Waltham Abbey. -

The Growth of London Through Transport Map of London’S Boroughs

Kingston The growth of London through transport Map of London’s boroughs 10 The map shows the current boundaries of London’s Key boroughs. The content of 2 1 Barking 17 Hillingdon this album relates to the & Dagenham 15 31 18 Hounslow area highlighted on the map. 14 26 2 Barnet 16 19 Islington This album is one of a 3 Bexley 20 Kensington series looking at London 17 4 6 12 19 4 Brent & Chelsea boroughs and their transport 1 25 stories from 1800 to the 5 Bromley 21 Kingston 9 30 present day. 33 7 6 Camden 22 Lambeth 23 Lewisham 7 City of London 13 20 28 8 Croydon 24 Merton 18 11 3 9 Ealing 25 Newham 22 32 23 26 Redbridge 27 10 Enfield 11 Greenwich 27 Richmond 28 Southwark 24 12 Hackney 29 Sutton Kingston 13 Hammersmith 21 5 & Fulham 30 Tower Hamlets 29 8 14 Haringey 31 Waltham Forest 15 Harrow 32 Wandsworth 16 Havering 33 Westminster A3 RICHMOND RIVER A307 THAMES ROAD KINGSTON A308 UPON Kingston Hill THAMES * * Kings Road Kingston A238 Turks Pier Norbiton * * Bentalls A3 * Market Place NEW * Cambridge* A2043 Road MALDEN Estates New Malden A307 Kingston Bridge Berrylands KINGSTON SURBITON RIVER THAMES UPON KINGSTON BY PASS THAMES Surbiton A240 A3 Malden Beresford Avenue* Manor Worcester Park A243 A309 A240 A3 Tolworth Haycroft* Estate HOOK A3 0 miles ½ 1 Manseld* Chessington Road North 0 kilometres 1 Chessington South A243 A3 A243 * RBK. marked are at theLocalHistoryRoom page. Thoseinthecollection atthebottomofeach are fortheimages References the book. can befoundatthebackof contributing tothisalbum Details ofthepartner theseries. -

Waltham Forest Archaeological Priority Area Appraisal October 2020

London Borough of Waltham Forest Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal October 2020 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Maria Medlycott, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 15/10/2020 Reviser(s): Tim Murphy Date of last revision: 23/11/2020 Date Printed: 23/11/2020 Version: 2 Status: Final 2 Contents 1 Acknowledgments and Copyright ................................................................................... 6 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 3 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 8 4 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers ................................................................................ 10 5 History of Waltham Forest Borough ............................................................................. 13 6 Archaeological Priority Areas in Waltham Forest.......................................................... 31 6.1 Tier 1 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 31 6.2 Tier 2 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 31 6.3 Tier 3 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 32 6.4 Waltham Forest APA 1.1. Queen Elizabeth Hunting Lodge GV II* .................... 37 6.5 Waltham Forest APA 1.2: Water House ............................................................... -

Two Brewers Epping Forest

Uif!Uxp!Csfxfst!jt!b!mpwfmz!tqbdjpvt!qvc! xjui!dpngpsubcmf!gvsnjuvsf!bne!b!xfmm. Uif!Uxp!Csfxfst!bne! tupdlfe!cbs/ Ibjnbvmu!Gpsftu-!Fqqjnh! A 3 mile circular pub walk from the Two Brewers in Chigwell Row, Essex. The walking route explores the adjacent Hainault Forest Country Park, with chance to see beautiful ancient Gpsftu-!Fttfy woodland, a pretty lake and even a city farm and zoo. Hfuujnh!uifsf Moderate Terrain Chigwell Row is situated in the triangle formed by the M11, M25 and A12, just a few miles north of Romford on the A1112. The walk starts and finishes at the Two Brewers pub on Lambourne Road, east of the main A1112. The pub has its own car park alongside. Alternatively, if this car park is very busy, turn left out of the pub and there is another car park for 4!njmft! the country park just a little further along on the right. Djsdvmbs!!!!! Approximate post code IG7 6ET. 2!up!2/6! Wbml!Tfdujpnt ipvst Tubsu!up!Dbnfmpu! Go 1 Dspttspbet 200114 Leave the pub car park and turn left along the pavement. Cross over Coopers Close and soon afterwards cross over the main road using the zebra crossing. Veer left into the small country park car park. A few paces in, turn left through the metal kissing gate and keep straight ahead on the grass path running close to the hedgeline on the left. Access Notes Cross the small wooden footbridge into the next field, and then cross this field diagonally right (at 2 o’clock) to reach the 1. -

London Tube by Zuti

Stansted Airport Chesham CHILTERN Cheshunt WATFORD Epping RADLETT Stansted POTTERS BAR Theobolds Grove Amersham WALTHAM CROSS WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING FOREST Chalfont & Watford Latimer Junction Turkey Theydon ENFIELD Street Bois Watford BOREHAMWOOD London THREE RIVERS Cockfosters Enfield Town ELSTREE Copyright Visual IT Ltd OVERGROUND Southbury High Barnet Zuti and the Zuti logo are registered trademarks Chorleywood Watford Oakwood Loughton Debden High Street NEW BARNET www.zuti.co.uk Croxley BUSHEY Rickmansworth Bush Hill Park Chingford Bushey Buckhurst Hill Totteridge & Whetstone Southgate Moor Park EDGWARE Shenfield Stanmore Edmonton Carpenders Park Green Woodside Park Arnos Grove Grange Hill MAPLE CROSS Edgware Roding Chigwell Hatch End Silver Valley Northwood STANMORE JUBILEE MILL HILL EAST BARNET Street Mill Hill East West Finchley LAMBOURNE END Canons Park Bounds Green Highams Hainault Northwood Hills Headstone Lane White Hart Park Woodford Brentwood Lane NORTHWOOD Burnt Oak WALTHAM STANSTED EXPRESS STANSTED Wood Green FOREST Pinner Harrow & Finchley Central Colindale Fairlop Wealdstone Alexandra Bruce South Queensbury HARINGEY Woodford Park Turnpike Lane Grove Tottenham Blackhorse REDBRIDGE NORTHERN East Finchley North Harrow HARROW Hale Road Wood GERARDS CROSS BARNET VICTORIA Street Harold Wood Kenton Seven Barkingside Kingsbury Hendon Central Sisters RUISLIP West Harrow Highgate Harringay Central Eastcote Harrow on the Hill Green Lanes St James Snaresbrook Walthamstow Fryent Crouch Hill Street Gants Ruislip Northwick Country South -

FCFCG London Map 08.Indd

1 5 9 13 18 22 26 30 34 38 42 47 Eden at St Pauls Community Surrey Docks Garden, Lambeth Farm, Southwark Walworth Garden Farm, Southwark Calthorpe Project A quiet green space benefi ting the whole King Henry’s Walk Mill Lane Gardening Roots and Shoots Wildlife A thriving 2.2 acre city farm, with projects for Community Garden, neighbourhood. Aims to create a sustainable Garden, Islington Project, Camden adults with learning diffi culties, schools and An environmental/horticultural training centre habitat for wildlife and to promote recycling Hackney City Farm, Hackney Garden, Lambeth young farmers. Meet our cows, donkeys, pigs, featuring a wildlife area and fruit, vegetable Camden and bio-diversity. Includes community An organic community garden with growing A horticultural training project for adults with sheep, chicken, geese, ducks and turkeys. Or and fl ower beds. Also polytunnels, a large Meet the animals in our cobbled farmyard, The garden has a summer meadow, two Bankside Open Spaces compost facilities, a children’s gardening club Heathrow Special Needs plots, beautiful planting, a wildlife pond and learning disabilities. We are open as a garden relax in the herb garden by the River Thames. greenhouse and bees. We run horticultural Community & Environment then relax in the beautiful organic garden. Our ponds, decorative beds, children’s shelter, A 1.2 acre garden described as an oasis by and volunteer days. woodland nature reserve. Run by volunteers, centre, selling potted bedding plants, shrubs training for the unemployed, an environmental Trust, Southwark award-winning café opens daily except Monday. Phoenix Garden, Camden dragon’s den and paradise corner. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2016, London

London Register 2016 HERITAGE AT RISK 2016 / LONDON Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Reducing the risks XI Key statistics XIV Publications and guidance XV Key to the entries XVII Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Greater London 1 Barking and Dagenham 1 Barnet 2 Bexley 5 Brent 5 Bromley 6 Camden 11 City of London 20 Croydon 21 Ealing 24 Enfield 27 Greenwich 30 Hackney 34 Hammersmith and Fulham 40 Haringey 43 Harrow 47 Havering 50 Hillingdon 51 Hounslow 58 Islington 64 Kensington and Chelsea 70 Kingston upon Thames 81 Lambeth 82 Lewisham 91 London Legacy (MDC) 95 Merton 96 Newham 101 Redbridge 103 Richmond upon Thames 104 Southwark 108 Sutton 116 Tower Hamlets 117 Waltham Forest 123 Wandsworth 126 Westminster, City of 129 II London Summary 2016 he Heritage at Risk Register in London reflects the diversity of our capital’s historic environment. It includes 682 buildings and sites known to be at risk from Tneglect, decay or inappropriate development - everything from an early 18th century church designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, to a boathouse built during WWI on an island in the Thames. These are sites that need imagination and investment. In London the scale of this challenge has grown. There are 12 more assets on the Heritage at Risk Register this year compared to 2015. We also know that it’s becoming more expensive to repair many of our buildings at risk. In the face of these challenges we’re grateful for the help and support of all those who continue to champion our historic environment. -

Mayor John Williams & Kingston's Fairfield. a Tribute To

MAYOR JOHN WILLIAMS & KINGSTON’S FAIRFIELD. A TRIBUTE TO JUNE SAMPSON, LOCAL HISTORIAN & JOURNALIST. David A Kennedy, PhD 25 NOVEMBER 2019 ABSTRACT John Williams, Mayor of Kingston in 1858, 1859 and 1864, was an energetic, public-spirited, self-educated man who had poor and humble beginnings. He came to Kingston in 1851 to take over the ailing Griffin Hotel which he developed into a flourishing enterprise that was highly regarded. He was instrumental in securing the Fairfield as a recreation ground for the townsfolk and played a part in improving the Promenade on the River Thames. While he acquired enemies, notably Alderman Frederick Gould, his civic funeral in 1872 and obituary tributes indicated that overall he was a greatly respected and valued man. Local historian June Sampson’s view that John Williams deserved greater recognition in Kingston was justified and a memorial in the Fairfield would seem appropriate for this. INTRODUCTION In 2006, June Sampson, distinguished local historian who was formerly the Surrey Comet’s Features Editor, wrote that Kingston upon Thames owed The Fairfield recreation ground to John Williams, who was Mayor of the town in 1858, 1859 and 1864.1 Earlier, she gave a fuller account of Williams’ struggle to have the Fairfield enclosed for the people, which came to fruition in 1865. However, it was not until 1889, after John Williams died in 1872, that the Fairfield was completely laid out and formally opened with a celebratory cricket match. June acknowledged the support that Williams received from Russell Knapp, the owner and editor of the Surrey Comet newspaper, which appeared to be her main source. -

20 Years in Epping Forest Seeing the Trees for the Wood

66 SCIENCE & OPINION Figure 1: Dulsmead beech soldiers. (Jeremy Dagley) 20 years in Epping Forest Seeing the trees for the wood Dr Jeremy Dagley, City of London Corporation’s Head of Conservation at Epping Forest There are more than 50,000 ancient pollards in Epping Forest. Most seems likely to be a little conservative. The of these lie within a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a number of living oaks is expected to top 10,000, despite many having died over the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and by any measure, cultural or last 30 years, and the total number of beeches ecological, they represent one of the most important populations looks likely to be closer to 20,000 than 15,000. However, defining individual beech trees in of old trees anywhere in Europe. The number is estimated from a some parts of the Forest is tricky because randomised survey carried out in the 1980s by a Manpower Services many are ‘coppards’, a variable mixture of Commission-led team, which concluded that there were around coppice stems, possible clonal growth and pollard heads. It will take some time to be sure 25,000 hornbeam, 15,000 beech and 10,000 oak pollards in total. of the final totals, but the aim is for the VTR to be a lasting record and one that ensures Biological recording The Epping Forest Veteran Tree our successors, to reverse an old proverb, It is a daunting number to consider managing, Register (VTR) can always see the trees for the wood. given the value of ancient trees and their relative rarity in Europe. -

Good Parks for London 2017

''The measure of any great civilisation is in its cities, and the measure of a city's greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, it's parks and squares.'' John Ruskin Sponsored by Part of Capita plc Contents Foreword..........................................................3 Part 2 Introduction.....................................................4 Signature Parks and green spaces City of London - Open space beyond the square mile...38 Overall scores...................................................8 Lee Valley Regional Park Authority............................40 Thamesmead - London’s largest housing landscape......42 Part 1 The Royal Parks......................................................43 Good Parks for London Criteria Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park..................................45 1. Public Satisfaction...........................................10 Landscape contractors 2. Awards for quality...........................................12 idverde - A whole system approach............................47 3. Collaboration with other Boroughs..................14 Glendale - Partnership in practice.............................49 4. Events.............................................................16 5. Health, fitness and well-being.........................20 Capel Manor - London’s land based college.........50 6. Supporting nature...........................................24 7. Community involvement.................................28 8. Skills development..........................................30 Valuing our parks