How Russia Wins the Climate Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Warming Impacts on Distributions of Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.) Seed Zones and Seed Mass Across Russia in the 21St Century

Article Climate Warming Impacts on Distributions of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Seed Zones and Seed Mass across Russia in the 21st Century Elena I. Parfenova 1, Nina A. Kuzmina 2, Sergey R. Kuzmin 2 and Nadezhda M. Tchebakova 1,* 1 Laboratory of Forest Monitoring, Sukachev Institute of Forest FRC KSC SB RAS, 660036 Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Forest Genetics and Breeding, Sukachev Institute of Forest FRC KSC SB RAS, 660036 Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] (N.A.K.); [email protected] (S.R.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Research highlights: We investigated bioclimatic relationships between Scots pine seed mass and seed zones/climatypes across its range in Russia using extensive published data to predict seed zones and seed mass distributions in a changing climate and to reveal ecological and genetic components in the seed mass variation using our 40-year common garden trial data. Introduction: seed productivity issues of the major Siberian conifers in Asian Russia become especially relevant nowadays in order to compensate for significant forest losses due to various disturbances during the 20th and current centuries. Our goals were to construct bioclimatic models that predict the seed mass of major Siberian conifers (Scots pine, one of the major Siberian conifers) in a warming climate during the current century. Methods: Multi-year seed mass data were derived from the literature and were collected during field work. Climate data (January and July data and annual precipitation) were Citation: Parfenova, E.I.; Kuzmina, derived from published reference books on climate and climatic websites. -

4. Trade Structure

TRADE STRUCTURE 4. TRADE STRUCTURE 4.1 Changing Nature of Global Container Trade Container shipping routes can be divided into three main groups: (1) East-West trades, which circle the globe in the Northern Hemisphere linking the major industrial centres of North America, Western Europe and Asia; (2) North-South trades articulating around major production and consumption centres of Europe, Asia and North America, and linking these centres with developing countries in the Southern Hemisphere; and (3) intraregional trades operating in shorter hauls and with smaller ships. North–south routes are Figure 4-1 shows study estimates of the container trade volumes (full export/import containers only) in 2002 and 2015 of each of trade groups. Container trade volumes on the East-West routes will increase from 34 million TEU in 2002 to 70 million TEU in 2015 representing 5.8 per cent of annual average growth rate. The study forecasts suggest that the intraregional trades will show solid growth from 28 million TEU to 72 million TEU with a compound average growth rate of 7.5 per cent per annum over the same period. The North-South trade is also expected to grow at a rate of 6.2 per cent per annum on average, exceeding the growth rate of the East-West trade. Figure 4-1: Container Trade by Trade Group (2002 and 2015) 80.00 70.00 60.00 50.00 2002 40.00 2015 Million TEU 30.00 20.00 10.00 0.00 East-West Intra-Regional North-South/South-South 32 TRADE STRUCTURE 4.2 Asia - North America The biggest deep sea liner route is the trans-Pacific trade between Asia and North America, representing 14.5 million TEU in 2002, equivalent to 43 per cent of the total East-West trade and 19 per cent of the world total. -

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil Tnap of the World 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil Map of the World

FAO-Unesco S oilmap of the 'world 1:5 000 000 Volume VII North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil tnap of the world 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil map of the world Volume I Legend Volume II North America Volume III Mexico and Central America Volume IV South America Volume V Europe Volume VI Africa Volume VII South Asia Volume VIIINorth and Central Asia Volume IX Southeast Asia Volume X Australasia FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION FAO-Unesco Soilmap of the world 1: 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia Prepared by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Unesco-Paris 1978 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not irnply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations or of the United Nations Educa- tional, Scientific and Cultural Organization con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delirnitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Printed by Tipolitografia F. Failli, Rome, for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Published in 1978 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris C) FAO/Unesco 1978 ISBN 92-3-101345-9 Printed in Italy PREFACE The project for a joint FAO/Unesco Soil Map of vested with the responsibility of compiling the techni- the World was undertaken following a recommenda- cal information, correlating the studies and drafting tion of the International Society of Soil Science. -

A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia

Informationen der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur in Europa bet-tfila.org/info Nr. 18 1+2/15 Fakultät 3, Technische Universität Braunschweig / Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem SPECIAL EDITION “Siberia” – SONDERAUSGABE „Sibirien“ “From Jerusalem to Birobidzhan” – A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia In August 2015, the team of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University Erstmalig erscheint aus aktuellem Anlass of Jerusalem undertook a research expedition to Siberia. Over the course of 21 eine Sonderausgabe von bet tfila.org/info: Im days, the expedition spanned 6,000 km. Overall, the CJA team visited 16 sites August 2015 konnte sich das deutsch-israe- in Siberia and the Russian Far East: Tomsk, Mariinsk, Achinsk, Krasnoyarsk, lische Team des Center for Jewish Art und Kansk, Nizhneudinsk, Irkutsk, Babushkin (former Mysovsk), Kabansk, Ulan- der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle einen lange Ude (former Verkhneudinsk), Barguzin, Petrovsk Zabaikalskii (former Petrovskii gehegten Wunsch erfüllen und das jüdische Zavod), Chita, Khabarovsk, Birobidzhan, and Vladivostok. Erbe in Sibirien und im „Fernen Osten“ Russlands dokumentieren. In drei Wochen 16 synagogues and 4 collections of ritual objects were documented alongside a legten die fünf Wissenschaftler (Prof. Aliza survey of 11 Jewish cemeteries and numerous Jewish houses. The team consisted Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. of Prof. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. Katrin Kessler (Bet Tfila, Katrin Keßler, Dr. Anna Berezin und Archi- Braunschweig), Dr. Anna Berezin, and architect Zoya Arshavsky. The expedi- tektin Zoya Arshavsky) auf ihrer Reise von tion was made possible with the generous donations of Mrs. Josephine Urban, Tomsk nach Vladivostok über 6.000 km zu- London, and an anonymous donor. -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

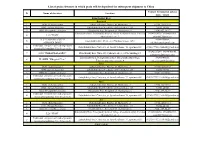

List of Grain Elevators in Which Grain Will Be Deposited for Subsequent Shipment to China

List of grain elevators in which grain will be deposited for subsequent shipment to China Contact Infromation (phone № Name of elevators Location num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky district, village Starotsuruhaytuy, Pertizan 89145160238, 89644638969, 4 LLS "PION" Shestakovich str., 3 [email protected] LLC "ZABAYKALSKYI 89144350888, 5 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 149/1 AGROHOLDING" [email protected] Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 6 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich 89242727249, 89144700140, 7 OOO "ZABAYKALAGRO" Zabaykalsky krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 147A, building 15 [email protected] Zabaykalsky krai, Priargunsky district, Staroturukhaitui village, 89245040356, 8 IP GKFH "Mungalov V.A." Tehnicheskaia street, house 4 [email protected] Corn 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 4 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich Rice 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. -

Études Finno-Ougriennes, 46 | 2014 the Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish Woman with Deep Blue Eyes 2

Études finno-ougriennes 46 | 2014 Littératures & varia The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes La mère de Dieu khantye et la Finnoise aux yeux bleus Handi Jumalaema ja tema süvameresilmadega soome õde: „Märgitud“ (1980) ja „Jumalaema verisel lumel“ (2002) Elle-Mari Talivee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/efo/3298 DOI: 10.4000/efo.3298 ISSN: 2275-1947 Publisher INALCO Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2014 ISBN: 978-2-343-05394-3 ISSN: 0071-2051 Electronic reference Elle-Mari Talivee, “The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes”, Études finno-ougriennes [Online], 46 | 2014, Online since 09 October 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/efo/3298 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/efo.3298 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Études finno-ougriennes est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes 1 The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes La mère de Dieu khantye et la Finnoise aux yeux bleus Handi Jumalaema ja tema süvameresilmadega soome õde: „Märgitud“ (1980) ja „Jumalaema verisel lumel“ (2002) Elle-Mari Talivee 1 In the following article, similarities between two novels, one by an Estonian and the other by a Khanty writer, are discussed while comparing possible resemblances based on the Finno-Ugric way of thinking. Introduction 2 One of the writers is Eremei Aipin, a well-known Khanty writer (born in 1948 in Varyogan near the Agan River), whose works have been translated into several languages. -

Country Profile: Russia Note: Representative

Country Profile: Russia Introduction Russia, the world’s largest nation, borders European and Asian countries as well as the Pacific and Arctic oceans. Its landscape ranges from tundra and forests to subtropical beaches. It’s famous for novelists Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, plus the Bolshoi and Mariinsky ballet companies. St. Petersburg, founded by legendary Russian leader Peter the Great, features the baroque Winter Palace, now housing part of the Hermitage Museum’s art collection. Extending across the entirety of northern Asia and much of Eastern Europe, Russia spans eleven time zones and incorporates a wide range of environments and landforms. From north west to southeast, Russia shares land borders with Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (both with Kaliningrad Oblast), Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China,Mongolia, and North Korea. It shares maritime borders with Japan by the Sea of Okhotsk and the U.S. state of Alaska across the Bering Strait. Note: Representative Map Population The total population of Russia during 2015 was 142,423,773. Russia's population density is 8.4 people per square kilometre (22 per square mile), making it one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world. The population is most dense in the European part of the country, with milder climate, centering on Moscow and Saint Petersburg. 74% of the population is urban, making Russia a highly urbanized country. Russia is the only country 1 Country Profile: Russia in the world where more people are moving from cities to rural areas, with a de- urbanisation rate of 0.2% in 2011, and it has been deurbanising since the mid-2000s. -

Newell, J. 2004. the Russian Far East

Industrial pollution in the Komsomolsky, Solnechny, and Amursky regions, and in the city of Khabarovsk and its Table 3.1 suburbs, is excessive. Atmospheric pollution has been increas- Protected areas in Khabarovsk Krai ing for decades, with large quantities of methyl mercaptan in Amursk, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide, phenols, lead, and Type and name Size (ha) Raion Established benzopyrene in Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk-on-Amur, and Zapovedniks dust prevalent in Solnechny, Urgal, Chegdomyn, Komso- molsk-on-Amur, and Khabarovsk. Dzhugdzhursky 860,000 Ayano-Maysky 1990 Between 1990 and 1999, industries in Komsomolsky and Bureinsky 359,000 Verkhne-Bureinsky 1987 Amursky Raions were the worst polluters of the Amur River. Botchinsky 267,400 Sovetsko-Gavansky 1994 High concentrations of heavy metals, copper (38–49 mpc), Bolonsky 103,600 Amursky, Nanaisky 1997 KHABAROVSK zinc (22 mpc), and chloroprene (2 mpc) were found. Indus- trial and agricultural facilities that treat 40 percent or less of Komsomolsky 61,200 Komsomolsky 1963 their wastewater (some treat none) create a water defi cit for Bolshekhekhtsirsky 44,900 Khabarovsky 1963 people and industry, despite the seeming abundance of water. The problem is exacerbated because of: Federal Zakazniks Ⅲ Pollution and low water levels in smaller rivers, particular- Badzhalsky 275,000 Solnechny 1973 ly near industrial centers (e.g., Solnechny and the Silinka River, where heavy metal levels exceed 130 mpc). Oldzhikhansky 159,700 Poliny Osipenko 1969 Ⅲ A loss of soil fertility. Tumninsky 143,100 Vaninsky 1967 Ⅲ Fires and logging, which impair the forests. Udylsky 100,400 Ulchsky 1988 Ⅲ Intensive development and quarrying of mineral resourc- Khekhtsirsky 56,000 Khabarovsky 1959 es, primarily construction materials. -

Nation Making in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals

Nation Making in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals and Surprising Results WILLIAM R. SIEGEL oday in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast (Yevreiskaya Avtonomnaya TOblast, or EAO), the nontitular, predominately Russian political leadership has embraced the specifically national aspects of their oblast’s history. In fact, the EAO is undergoing a rebirth of national consciousness and culture in the name of a titular group that has mostly disappeared. According to the 1989 Soviet cen- sus, Jews compose only 4 percent (8,887/214,085) of the EAO’s population; a figure that is decreasing as emigration continues.1 In seeking to uncover the reasons for this phenomenon, I argue that the pres- ence of economic and political incentives has motivated the political leadership of the EAO to employ cultural symbols and to construct a history in its effort to legitimize and thus preserve its designation as an autonomous subject of the Rus- sian Federation. As long as the EAO maintains its status as one of eighty-nine federation subjects, the political power of the current elites will be maintained and the region will be in a more beneficial position from which to achieve eco- nomic recovery. The founding in 1928 of the Birobidzhan Jewish National Raion (as the terri- tory was called until the creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934) was an outgrowth of Lenin’s general policy toward the non-Russian nationalities. In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks faced the difficult task of consolidating their power in the midst of civil war. In order to attract the support of non-Russians, Lenin oversaw the construction of a federal system designed to ease the fears of—and thus appease—non-Russians and to serve as an example of Soviet tolerance toward colonized peoples throughout the world. -

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin (Princeton University) Copyright (c) 1996 by the Slavic Research Center All rights reserved. The Russian empire's eventual displacement of the thirteenth-century Mongol ulus in Eurasia seems self-evident. The overthrow of the foreign yoke, defeat of various khanates, and conquest of Siberia constitute core aspects of the narratives on the formation of Russia's identity and political institutions. To those who disavow the Mongol influence, the Byzantine tradition serves as a counterweight. But the geopolitical turnabout is not a matter of dispute. Where Chingis Khan and his many descendants once held sway, the Riurikids (succeeded by the Romanovs) moved in. *1 Rather than the shortlived but ramified Mongol hegemony, which was mostly limited to the middle and southern parts of Eurasia, longterm overviews of the lands that became known as Siberia, or of its various subregions, typically begin with a chapter on "pre-history," which extends from the paleolithic to the moment of Russian arrival in the late sixteenth, early seventeenth centuries. *2 The goal is usually to enable the reader to understand what "human material" the Russians found and what "progress" was then achieved. Inherent in the narratives -- however sympathetic they may or may not be to the native peoples -- are assumptions about the historical advance deriving from the Russian arrival and socio-economic transformation. In short, the narratives are involved in legitimating Russia's conquest without any notion of alternatives. Of course, history can also be used to show that what seems natural did not exist forever but came into being; to reveal that there were other modes of existence, which were either pushed aside or folded into what then came to seem irreversible.