Roberto Clemente

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Clemente Quietly Grew in Stature by Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.Com

Clemente quietly grew in stature By Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.com "It's not just a death, it's a hero's death. A lot of athletes do wonderful things – but they don't die doing it," says former teammate Steve Blass about Roberto Clemente on ESPN Classic's SportsCentury series. Playing in an era dominated by the likes of Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente was usually overlooked by fans when they discussed great players. Not until late in his 18- year career did the public appreciate the many talents of the 12-time All-Star of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Of all Clemente's skills, his best tool was his right arm. From rightfield, he unleashed lasers. He set a record by leading the National League in assists five seasons. He probably would have led even more times, but players learned it wasn't wise to run on Clemente. Combined with his arm, his ability to track down fly balls earned him Gold Gloves the last 12 years of his career. At bat, Clemente seemed uncomfortable, rolling his neck and stretching his back. But it was the pitchers who felt the pain. Standing deep in the box, the right-handed hitter would drive the ball to all fields. After batting above .300 just once in his first five seasons, Clemente came into his own as a hitter. Starting in 1960, he batted above .311 in 12 of his final 13 seasons, and won four batting titles in a seven-year period. Clemente's legacy lives on -- look no farther than the number on Sammy Sosa's back. -

Baseball Cards of the 1950S: a Kid’S View Looking Back by Tom Cotter CBS and NBC All Broadcast Televised Games in the 1950S and On

Like us and Devoted to Antiques, follow us Collectibles, on Furniture, Art and Facebook Design. May 2017 EstaBLIshEd In 1972 Volume 45, number 5 Baseball Cards of the 1950s: A Kid’s View Looking Back By Tom Cotter CBS and NBC all broadcast televised games in the 1950s and on. 1950 saw the first televised All-Star game; 1951 While I am not sure what got us started, about 1955 the premier game in color; 1955 the first World Series in we began collecting baseball cards (my brother was eight, color (NBC); 1958 the beginning televised game from the I was five). I suspect it was reasonably inexpensive and West Coast (L.A. Dodgers at S.F. Giants with Vin Scully we were certainly in love with baseball. We lived in Wi - announcing); and 1959 the number one replay (requested chita, Kansas, which in the 1950s had minor league teams by legend Mel Allen of his producer.) In 1950, all 16 (Milwaukee Braves AAA affiliate 1956-1958), although I Major League teams were from St. Louis to the East Coast don’t recall that we went to any games. However, being and mostly trains were used for travel. The National somewhat competitive and playing baseball all summer, League contained: Boston Braves, New York Giants, we each chose a team to root for and rather built our base - Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburg Pirates, ball card collections around those teams. My brother’s Cincinnati Redlegs (1953-1960 no “Reds” during the Mc - favorite team was the Chicago Cubs, with perennial All- Carthy Era), Chicago Cubs, and St. -

Shir Notes the Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018

Shir Notes The Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 16, Number 6, June 2018. Affiliated with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Rabbi’s Column Events . We’re going to dedicate a Ner Tamid at the end of this of the Month month. Shabbat services at It was designed by us but hand-made in Israel reflecting our de Toledo High School name and the congregation’s musical emphasis. I’d post a picture, but we Saturday, June `9 - 10:30 am Birthday Shabbat want the reveal on June 23 to be our first view of this artistic endeavor! Saturday, June 23 - 10:30 am The Eternal Light is often associated with the menorah, the seven-branched Anniversary Shabbat lamp stand which was part of the Bet HaMikdash – the Holy Temple in Ner Tamid dedication Jerusalem. (See article on page 2) Kiddush lunch for Ethyl Granik’s The rabbis interpreted the Ner Tamid as a symbol of God’s eternal presence 90th birthday in the world. --------------------------------------------- Walk Around Lake Balboa Originally the Ner Tamid was an oil lamp. Ours will be a battery powered Sunday, June 3, 9:00 am bulb. It’s supposed to be “eternal” but how long the batteries last will determine that. Our Walk this year raises money for the Painted Turtle Camp for Obviously, we have been able to manage without a Ner Tamid this long, so seriously ill children. Call Sheilah what will this light add to our lives? Hart at (818) 884-2342. See article on page 4 and flyer. The light shines above the ark, repository of the Torah scrolls. -

Negro Leaguers in Service If They Can Fight and Die on Okinawa and Guadalcanal in the South Pacific, They Can Play Baseball in America

Issue 37 July 2015 Negro Leaguers in Service If they can fight and die on Okinawa and Guadalcanal in the South Pacific, they can play baseball in America. Baseball Commissioner AB "Happy" Chandler This edition of the Baseball in Wartime Newsletter is dedicated to all the African- American baseball players who served with the armed forces during World War II. More than 200 players from baseball’s Negro Leagues entered military service between 1941 and 1945. Some served on the home front, while others were in combat in Europe, North Africa and the Pacific. These were the days of a segregated military and life was never easy for these men, but, for some, playing baseball made the summer days a little more bearable. Willard Brown and Leon Day (the only two black players on the team) helped the OISE All-Stars win the European Theater World Series in 1945, Joe Greene helped the 92nd Infantry Division clinch the Mediterranean Theater championship the same year, Jim Zapp was on championship teams in Hawaii in 1943 and 1944, and Larry Doby, Chuck Harmon, Herb Bracken and Johnny Wright were Midwest Servicemen League all- stars in 1944. Records indicate that no professional players from the Negro Leagues lost their lives in service during WWII, but at least two semi-pro African-American ballplayers made the ultimate sacrifice. Grady Mabry died from wounds in Europe in December 1944, and Aubrey Stewart was executed by German SS troops the same month. With Brown and Day playing for the predominantly white OISE All-Stars, Calvin Medley pitching for the Fleet Marine Force team in Hawaii, and Don Smith pitching alongside former major leaguers for the Greys in England, integrated baseball made its appearance during the war years and quite possibly paved the way for the signing of Jackie Robinson. -

MEDIA and LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS of LATINOS in BASEBALL and BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of T

MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Mihir Parekh 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor, Dr. William Arcé, whose knowledge and expertise in Latino studies were vital to this project. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Timothy Morris and Dr. James Warren, for the assistance they provided at all levels of this undertaking. Their wealth of knowledge in the realm of sport literature was invaluable. To my family: the gratitude I have for what you all have provided me cannot be expressed on this page alone. Without your love, encouragement, and support, I would not be where I am today. Thank you for all you have sacrificed for me. April 22, 2015 iii Abstract MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION Mihir D. Parekh, MA The University of Texas at Arlington, 2015 Supervising Professors: William Arcé, Timothy Morris, James Warren The first chapter of this project looks at media representations of two Mexican- born baseball players—Fernando Valenzuela and Teodoro “Teddy” Higuera—pitchers who made their big league debuts in the 1980s and garnered significant attention due to their stellar play and ethnic backgrounds. Chapter one looks at U.S. media narratives of these Mexican baseball players and their focus on these foreign athletes’ bodies when presenting them the American public, arguing that 1980s U.S. -

PROFESSIONAL SPORT 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 12 100Campeones Text.Qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 13

100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 11 PROFESSIONAL SPORT 100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 12 100Campeones_Text.qxp 8/31/10 8:12 PM Page 13 2 LATINOS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL by Richard Lapchick A few years ago, Jayson Stark wrote, “Baseball isn’t just America’s sport anymore” for ESPN.com. He concluded that, “What is actu- ally being invaded here is America and its hold on its theoretical na- tional pastime. We’re not sure exactly when this happened—possi- bly while you were busy watching a Yankees-Red Sox game—but this isn’t just America’s sport anymore. It is Latin America’s sport.” While it may not have gone that far yet, the presence of Latino players in baseball, especially in Major League Baseball, has grown enormously. In 1990, the Racial and Gender Report Card recorded that 13 percent of MLB players were Latino. In the 2009 MLB Racial and Gender Report Card, 27 percent of the players were La- tino. The all-time high was 29.4 percent in 2006. Teams from South America, Mexico, and the Caribbean enter the World Baseball Classic with superstar MLB players on their ros- ters. Stark wrote, “The term, ‘baseball game,’ won’t be adequate to describe it. These games will be practically a cultural symposium— where we provide the greatest Latino players of our time a monstrous stage to demonstrate what baseball means to them, versus what baseball now means to us.” American youth have an array of sports to play besides base- ball, including soccer, basketball, football, and hockey. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

NOT JUST a GAME Featuring Dave Zirin

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION STUDY GUIDE NOT JUST A GAME Featuring Dave Zirin Study Guide Written by SCOTT MORRIS please visit www.mediaed.org/wp/notjustagame for updated materials & resources 2 CONTENTS Note to Educators ………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Overview ……………………………………………………………………………………...4 Pre-viewing Questions …………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Key Points …………………………………………………………………………………………5 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………….5 Assignments ………………………………………………………………………………………6 In the Arena ……………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Key Points …………………………………………………………………………………………7 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………….8 Assignments ………………………………………………………………………………………9 Like a Girl ………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….10 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...12 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….13 Breaking the Color Barrier ……………………………………………………………………………15 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….15 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...15 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….16 The Courage of Athletes ……………………………………………………………………………..18 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….18 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...19 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….20 3 NOTE TO EDUCATORS This study guide is designed to help you and your students engage and manage the information presented in this video. -

“As He Sees It”

“Baseball took my sight away, but it gave me Phone: (973) 275-2378 / [email protected] a life,” - Ed Lucas Ed Lucas – A Biography In Brief… “As He Sees It” Lucas, a native of New Jersey attended college at Seton Hall University (’62) and upon graduation was An Exhibit on the able to parlay his love of baseball into a lifelong career Extraordinary Life & Accomplishments as a freelance baseball reporter who has interviewed of Expert Baseball Reporter… countless baseball players, administrators and personalities over the last five decades. His work and Ed Lucas accomplishments have been lauded in many ways either through countless by-lines, or as the featured subject in various media accounts. For more A Biographical & Baseball-Oriented information about Ed Lucas please consult the Retrospective remainder of this brochure along with Ron Bechtel’s recent article – “For The Love Of The Game” (Seton Hall University Magazine, 26-29, Winter/Spring 2007) and featured homepage – http://www.edlucas.org “As He Sees It” An Exhibit on the Extraordinary Life & Accomplishments of Expert Baseball Reporter… Ed Lucas Special Thanks To… Jeannie Brasile, Director of the Walsh Library Gallery Jason Marquis, Volunteer Walsh Library Gallery Window Exhibit G. Gregory Tobin, Author & Reference Source Dr. Howard McGinn, Dean of University Libraries Sponsored By The For More Information Please Contact… Msgr. William Noé Field Archives & Alan Delozier, University Archivist & Exhibit Curator Special Collections Center would ultimately secure in later years in such periodicals as Baseball Digest, New York Times, Newark Star-Ledger, Sports Illustrated and even the book – “Bronx Zoo” by Sparky Lyle. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

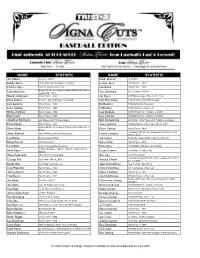

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Pdf, 241.15 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Music Transition “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:20 Jesse Host Coming to you from my home in the city I live in, the city of angels, Thorn it’s Bullseye. I’m Jesse Thorn. Didn’t write that. Just about every year on Bullseye, we bring you a week dedicated to my favorite sport, baseball. We usually try and put it out around opening day. Of course, baseball is very different this year. The season started late, the stadiums are almost empty, and by the time the airs, it’s possible that the season will not exist anymore. So, this year’s Bullseye Baseball Week is gonna be a little different, too. We’re gonna talk about baseball’s history. First up: an interview with Bob Kendrick. Bob is the president of the Negro League Baseball Museum. He’s had that job for almost a decade. The NLBM is pretty much the only place in the world dedicated to telling the story of the Negro Leagues—the leagues that gave rise to players like Hank Aaron, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and Satchel Paige. Not to mention, of course, the many players who were never allowed to play Major League Baseball.