They Played for the Love of the Game Adding to the Legacy of Minnesota Black Baseball Frank M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phillies' Victorino Gets Dumped On, Becomes Latest Pour Man's Al Smith by Paul Ladewski Posted on Monday, August

Phillies’ Victorino gets dumped on, becomes latest pour man’s Al Smith By Paul Ladewski Posted on Monday, August 17th One-time White Sox outfielder Al Smith was a productive hitter for much of his 12 seasons in the major leagues, but the three-time All-Star is best remembered neither for any of his 1,466 career hits nor his Negro League exploits before them. Fifty years after the fact, any mention of Smith immediately stokes memories of Game 2 of the 1959 World Series, when he took perhaps the most famous beer bath in baseball history. As the headline of his New York Times obituary said, “Al Smith, 73, Dies; Was Doused in Series.” Smith passed away in January, 2002, but his name came to light again last Wednesday night, when Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Shane Victorino was doused by an overzealous Cubs fan at Wrigley Field. Compared to what Smith endured, Victorino has no reason to cry in his beer. At least he was able to catch the ball on the warning track in left-center field. On that Friday, Oct. 2, afternoon at Comiskey Park, Smith could only watch helplessly while the ball hit by Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman Charlie Neal landed several feet into the lower deck in left field. Mere fractions of seconds earlier, in his haste to retrieve the ball, a fan named Melvin Piehl inadvertently knocked over a full cup of beer from atop the ledge of the wall. “It hit the bill of my cap and came down the side of my face,” Smith recalled years later. -

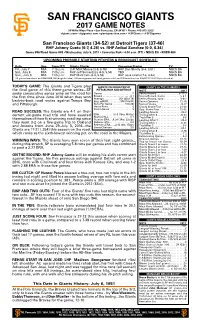

07.5.17 SF At

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2017 GAME NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza • San Francisco, CA 94107 • Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • giantspressbox.com • @SFGiants • @SFGigantes San Francisco Giants (34-52) at Detroit Tigers (37-46) RHP Johnny Cueto (6-7, 4.26) vs. RHP Anibal Sanchez (0-0, 6.34) Game #86/Road Game #48 • Wednesday, July 5, 2017 • Comerica Park • 4:10 p.m. (PT) • NBCS BA • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: Date Opp Time (PT) Giants Starter Opposing Starter TV Fri., July 7 MIA 7:15 p.m. LHP Matt Moore (3-8, 5.78) RHP Dan Straily (6-4, 3.51) NBCS BA Sat., July 8 MIA 7:05 p.m. RHP Jeff Samardzija (4-9, 5.54) TBD NBCS BA Sun., July 9 MIA 1:05 p.m. RHP Matt Cain (3-8, 5.58) RHP José Ureña (7-3, 3.43) NBCS BA All games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio). All home games and road games in LA and SD broadcast on KXZM 93.7 FM (Spanish radio). TODAY'S GAME: The Giants and Tigers play GIANTS ON ROAD TRIP AT GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS the inal game of this three-game series...SF PITTSBURGH AND DETROIT NOTE 2017 seeks consecutive series wins on the road for Games ......................5 Series Record ............... 8-15-3 the irst time since June 2016 when they won Record ....................4-1 Series Record, home .......... 5-6-1 Average .......... .251 (45x179) Series Record, road ........... 3-9-2 back-to-back road series against Tampa Bay Avg. -

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

Ahc CAR 015 017 007-Access.Pdf

•f THE...i!jEW===¥i^i?rmiES, DAY, OCTOBER 22, 19M. ly for Per^i^sion to Shift to Atlanta Sra ves/Will Ask Leag ^ ^ " ' NANCE DOEMOB, Ewbank Calls for Top Jet Effort ISl A gainstUnbeatenBillsSaturday ELECTRONICS SYRACUSE By DEANE McGOWEN llback, a DisappointmEnt The Buffalo Bills, the only un The Bills also lead in total of defeated team in professional fense—397 yards a game, 254 2 Years, Now at Pea football, were the primary topic yards passing and 143 rushing. statement Given Out Amid of conversation at the New Jets Have the Power By ALLISON DANZIG York Jets' weekly luncheon yes High Confusion — Giles Calls Special to The New York Times terday. The Jets' tough defense plus SYRACUSE, Oct. 21 — Af The Jets go to Buffalo to face the running of Matt Snell and Tuner complete the passing of Dick Wood are Owners to Meeting Here two years of frustration, the Eastern Division leaders of being counted on by Ewbank to once Nance is finally performing the American Football League Saturday night, and for the handle the Bills. like another Jim Brown, find Snell, the rookie fullback who 0 watt Stereo Amplifier ModelXA — CHICAGO, Oct. 21 (AP)— Syracuse finds itself among the charges of Weeb Ewbank the ^udio Net $159.95 CQR OA pulverizes tacklers with his in New low price i^WviUU The Milwaukee Braves board of top college football teams ill the game will be the moment of stant take-off running and his directors voted today to request nation The Orange is leading truth. second-effort power, is the New .mbert "Their personnel is excellent AM, FM. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions

Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions Joseph J. McMahon Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph J. McMahon Jr., A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions, 2 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 213 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McMahon: A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF BASEBALL'S THREE ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS JOSEPH J. MCMAHON, JR.* AND JOHN P. RossI** I. INTRODUCTION What is professional baseball? It is difficult to answer this ques- tion without using a value-laden term which, in effect, tells us more about the speaker than about the subject. Professional baseball may be described as a "sport,"' our "national pastime,"2 or a "busi- ness."3 Use of these descriptors reveals the speaker's judgment as to the relative importance of professional baseball to American soci- ety. Indeed, all of the aforementioned terms are partially accurate descriptors of professional baseball. When a Scranton/Wilkes- Barre Red Barons fan is at Lackawanna County Stadium 4 ap- plauding a home run by Gene Schall, 5 the fan is engrossed in the game's details. -

Want and Bait 11 27 2020.Xlsx

Year Maker Set # Var Beckett Name Upgrade High 1967 Topps Base/Regular 128 a $ 50.00 Ed Spiezio (most of "SPIE" missing at top) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 149 a $ 20.00 Joe Moeller (white streak btwn "M" & cap) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 252 a $ 40.00 Bob Bolin (white streak btwn Bob & Bolin) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 374 a $ 20.00 Mel Queen ERR (underscore after totals is missing) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 402 a $ 20.00 Jackson/Wilson ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 427 a $ 20.00 Ruben Gomez ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 447 a $ 4.00 Bo Belinsky ERR (incomplete stat line) 1968 Topps Base/Regular 400 b $ 800 Mike McCormick White Team Name 1969 Topps Base/Regular 47 c $ 25.00 Paul Popovich ("C" on helmet) 1969 Topps Base/Regular 440 b $ 100 Willie McCovey White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 447 b $ 25.00 Ralph Houk MG White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 451 b $ 25.00 Rich Rollins White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 511 b $ 25.00 Diego Segui White Letters 1971 Topps Base/Regular 265 c $ 2.00 Jim Northrup (DARK black blob near right hand) 1971 Topps Base/Regular 619 c $ 6.00 Checklist 6 644-752 (cprt on back, wave on brim) 1973 Topps Base/Regular 338 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 1973 Topps Base/Regular 588 $ 20.00 Checklist 529-660 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 263 $ 3.00 Checklist 133-264 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 273 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 upgrd exmt+ 1956 Topps Pins 1 $ 500 Chuck Diering SP 1956 Topps Pins 2 $ 30.00 Willie Miranda 1956 Topps Pins 3 $ 30.00 Hal Smith 1956 Topps Pins 4 $ -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1954-10-02

Giants :f,ak·e 3d ,S'trai.ght From I hdians I -6-2. Rhode·sHils The Weather Pinch Single p...u, elOlUb ..... - • • Iooal II ........' . ......n. Noi _II e..... e .. ie.- To Tie Mark peratue. Low. 51; billa, 68. By JACK HAND CLEVELAND (A")- Pinchhlt Est. 1868 - AP Lea!.d Wire, Wirephoto - Five Cents Iowa City, Iowa, Saturday, Oct. 2, 1954 ter Dusty Rhodes came through again and Willie Mays started hitting as the alert New York Welch Meets the PreIS'" Giants shoved the shoddy-field I llli Cleveland [ndians to the edge of the cUft Friday with a third straight World Series victory. Hoyt Wllhelm strode from Manager Leo Durocher's well stocked bullpen with his puzzling Y knuckler to nail dQwn a 6-2 New York triumph when Puerto Ri can Ruben Gomez weakened in Hawks M the eighth after a blazing seven inning job. Rhodes, the spectacular clutch Only About Cleveland, hitter who won the first two for Welch Says Montana · . the Inspired National league champs, rose from the bench to The bow tie and ,enUe smile deUver a key two-run pinch sin which beCame t~illar to ~l gle in tile third, tying a series llons of TV viewers la.st May In Stadium record set by the Yanks' Bobby during the army-McCarthy hear Brown In 1947. BT GENE 1N000E Bakl in 3d InDinr Ings distinguished th~ Boston DaU,. ...... borla EdUo, Rhodes won the first game lawyer from the crowd as he There'll be a lot of scorinl this with a 10th inning ;homer and stepped from a plane late Friday afternoon when the [owa Hawk ,ot another homer Thursday In afternoon at the Iowa Cll,.