By the 18Th Century the Clan Ranald Was a Significant Element Part of That Church. Firstly, the Cl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daliburgh, St.Peter's Hall

DALIBURGH, ST.PETER’S HALL Mar 2014 Mick Andrew General Information Address: St.Peter’s Hall, Daliburgh, South Uist, Western Isles HS8 5SS - Venue is on C88 Daliburgh to Kilphedir road on RHS opposite church approx ½ mile from Borrdale Hotel. Car park available. - Built 1970’s. - Capacity approx 160 if stage used, 70–80 if performing on floor. Non- interlocking padded stacking chairs. - Mobile reception good for some networks. - Daliburgh has a hotel, petrol & Co-op with cashpoint; Bank at Lochboisdale (3 miles), other services at Benbecula (23 miles). Hall Details - Hall Dimensions: 16.89M (55’5”) long x 6.83M (22’5”) wide. Height at side walls 3.35M (11’) rising to 4.14M (13’7”) over central area. - Stage: 4.33M (14’2”) wide x 4.09M (13’5”) deep. Height of pros arch 2.49M (8’2”), height of stage 0.91M (3’). Wings 1.35M (4’5”) both sides. - Décor: Floor light wood with Badminton Court markings, walls wood clad lower, white upper and white roof. Green FOH tabs. - Get-in: reasonable, through FOH entrance, straight, flat, 1 wide single door & 1 double door. Approx 20M from van loading area to stage. 0.84M (2’9”) wide x 2M (6’7”) high. - Acoustics good. - Blackout partial. Windows have light unlined curtains. - Heating by radiators. 2 - No Piano. No Smoke Detectors - Small A-frame stepladder available. Technical - Power: 100amp 3-phase incomer & distribution board in foyer. 40amp trip feeds distribution board in SR wing. Hall 13amp sockets on 30amp trip. - No Stage lighting. - Small portable PA system available – 7 channel Phonic mixer amp, JBL speakers, amp, microphones, CD player. -

Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair Mcintosh

Offprint of chapter by Alastair Mclntosh - The 'Sacredness' of Natural Sites and Their Recovery: lona, Harris and Govan in Scotland, 2012 (full reference on final page). The full text of this book can be downloaded free from: IUCN www.iucn.org/dbtw-wpd/edocs/2012-006.pdf METSAHALLITUS ^WCPA ~~ WORLD COMMISSION ON PROTECTED AREAS The ‘sacredness’ of natural sites and their recovery: Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair McIntosh Science and the sacred: with which science can, and even a necessary dichotomy? should, meaningfully engage? It is a pleasing irony that sacred natural In addressing these questions science sites (SNSs), once the preserve of reli- most hold fast to its own sacred value – gion, are now drawing increasing rec- integrity in the pursuit of truth. One ap- ognition from biological scientists (Ver- proach is to say that science and the schuuren et al., 2010). At a basic level sacred cannot connect because the for- this is utilitarian. SNSs frequently com- mer is based on reason while the latter prise rare remaining ecological ‘is- is irrational. But this argument invariably lands’ of biodiversity. But the very exist- overlooks the question of premises. ence of SNSs is also a challenge to sci- Those who level it make the presump- ence. It poses at least two questions. tion that the basis of reality is materialis- Does the reputed ‘sacredness’ of these tic alone. The religious, by contrast, ar- sites have any significance for science gue that the basis of reality, including beyond the mere utility by which they material reality, is fundamentally spiritu- happen to conserve ecosystems? And al. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Fulled Wool Scarves Multiple Projects on the Same Threading

Fulled Wool Scarves multiple projects on the same threading MADELYN VAN DER HOOGT Choose from a fabulous array of colors and make lots of scarves for quick and easy holiday gifts. Change weft colors for different looks on the same warp—or change the colors of the warp, too! Simply tie a new warp onto the one you’ve just finished. The setts of both the warp and the weft in this project are very open to allow maximum fulling to take place during wet finishing. The result is a wonderfully soft, thick, cuddly, warm winter scarf. hese two scarves were woven on dif- secure them in front of the reed. ferent warps, both of Harrisville Then, taking the first end of the old T Shetland, one in Garnet, the other warp and the first end of the new warp on in Peacock. Both yarns are somewhat one side (right side if you are right hand- “heathered” (flecks of other colors are spun ed, left side if you are left-handed), tie into the yarn), a quality that makes them them together in an overhand knot. Re- work well with a variety of weft colors. peat with the next end from each warp and You can choose to weave many scarves on continue until all ends are tied. The knots one very long warp or even tie on new do not have to be exactly at the same point warps to change scarf colors completely. for every tie. Especially with wool, small Whatever you choose, you’ll find the tension differences between the threads weaving easy and fun. -

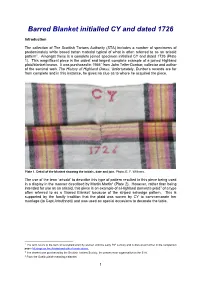

Barred Blanket Initialled CY and Dated 1726

Barred Blanket initialled CY and dated 1726 Introduction The collection of The Scottish Tartans Authority (STA) includes a number of specimens of predominately white based tartan material typical of what is often referred to as an arisaid pattern1. Amongst these is a complete joined specimen initialled CY and dated 1726 (Plate 1). This magnificent piece is the oldest and largest complete example of a joined Highland plaid/blanket known. It was purchased in 19662 from John Telfer Dunbar, collector and author of the seminal work The History of Highland Dressi. Unfortunately, Dunbar’s records are far from complete and in this instance, he gives no clue as to where he acquired the piece. Plate 1. Detail of the blanket showing the initials, date and join. Photo: E. F. Williams. The use of the term ‘arisaid’ to describe this type of pattern resulted in this piece being used in a display in the manner described by Martin Martinii (Plate 2). However, rather than being intended for use as an arisaid, this piece is an example of a Highland domestic plaid3 of a type often referred to as a ‘Barred Blanket’ because of the striped selvedge pattern. This is supported by the family tradition that the plaid was woven by CY to commemorate her marriage (to Capt Arbuthnott) and was used on special occasions to decorate the table. 1 The term refers to the form of over-plaid worn by women until the early 18th century and is discussed further in the companion paper Musings on the Arisaid and other female dress. -

Towards a Sonic Methodology Cathy

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 11, No. 2, 2016, pp. 343-358 Mapping the Outer Hebrides in sound: towards a sonic methodology Cathy Lane University of the Arts London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off the West Coast of Scotland, and the islands have a rich and distinctive cultural identity, as well as a complex history of settlement and migrations. Almost every geographical feature on the islands has a name which reflects this history and culture. This paper discusses research which uses sound and listening to investigate the relationship of the islands’ inhabitants, young and old, to placenames and the resonant histories which are enshrined in them and reveals them, in their spoken form, as dynamic mnemonics for complex webs of memories. I speculate on why this ‘place-speech’ might have arisen from specific aspects of Hebridean history and culture and how sound can offer a new way of understanding the relationship between people and island toponymies. Keywords: Gaelic, island, landscape, memory, Outer Hebrides, place-speech, sound © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction I am a composer, sound artist and academic. In my creative practice I compose concert works and gallery installations. My current practice focuses around sound-based investigations of a place or theme and uses a mixture of field recording, interview, spoken text and existing oral history archive recordings as material. I am interested in the semantic and the abstract sonic qualities of all this material and I use it to construct “docu-music” (Lane, 2006). -

Battle of Culloden

Battle of Culloden The Battle of Culloden (Scottish Gaelic: Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart fought loyalist troops commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. The Hanoverian victory at Culloden decisively halted the Jacobite intent to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the British throne; Charles Stuart never mounted any further attempts to challenge Hanoverian power in Great Britain. Between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded in the brief battle. The aftermath of the battle and subsequent crackdown on Jacobitism was brutal, earning Cumberland the sobriquet "Butcher". Efforts were subsequently taken to further integrate the comparatively wild Highlands into the Kingdom of Great Britain; civil penalties were introduced to weaken Gaelic culture and destroy the Scottish clan system. On the 16th April, 1746, one of the two Macdonald’s of Sleat, Capt. Donald Roy Macdonald, took part in the battle of Culloden. In the retreat he twice saw Alexander of Keppoch fall to the ground wounded. After the second fall Keppoch looked up at Donald Roy and said: "O God, have mercy upon me. Donald do the best for yourself, for I am gone." Donald Roy then left him and in leaving the field he received a musket wound which went in at the sole of the left foot and out at the buckle. During the eight week period he was hiding in three caves, wounded, alone and in pain, in wrote the following Latin Laments - now translated into English, revealing his thoughts and feelings - a vivid reflection of this highlander in context of post Culloden 1746. -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds ~~.. :~"."~ '''·;;;i;:;U;jU-_ . .. _ _.u.::,-::": _• .••• :.".;U.... ~ . ... ~. " .- :, .. ~~.~;;:;~~;~~;:.~::::::;:'~ The Journal of The Scottish Ornithologists' Club Vol. 4 No. 1 Spring 1966 FIVE SHILLINGS Zeiss Binoculars of entirely new design: Dialyt 8x30B giving equal performance with or without spectacles This delightfully elegant and compact new model from Carl Zeiss has an entirely new prism system which gives an amazing reduction in size. The special design also gives the fullest field of view-1 30 yards at 1 ODD-to spectacle wearers and to the naked eye alike. Price £53.10.0 fl1 h dt Write for the latest camera. binocular !Ul ~ egen ar and sunglass booklets to the sole , U.K. Importers. DEGENHARDT & CO lTD CARl ZEISS HOUSE 20/22 Mortimer Street· london, W.1 ?-.IUS 8050 (9 lines) CHOOSING A BINOCULAR OR A TELESCOPE EXPERT ADVICE From a Large Selection ... New and Secondhand G. HUTCHISON & SONS Phone CAL. 5579 OPTICIANS 18 FORREST ROAD, EDINBURGH Open till 5.30 p.m. Saturdays : Early closing Tuesday COLOUR BIRD BOOKS SLIDES of BIRDS Please support Incomparable Collection of THE S.O.C. British, European and African birds. Also views and places BIRD BOOKSHOP throughout the world. Send by buying all your new stamp for list. Sets of 100 for hire. Bird Books from THE SCOTTISH CENTRE BINOCULARS FOR ORNITHOLOGY AND BIRD PROTECTION Our "Birdwatcher 8 x 30" 21 Regent Terrace, model is made to our own specifications-excellent value Edinburgh 7 at 15 gns. Handy and practical to use. Ross, Barr and Stroud, Zeiss, All books sent post free Bosch Binoculars in stock. -

Line of March

NYC TARTAN DAY PARADE - April 8, 2017 LINE OF MARCH FIRST DIVISION: West 44th Street from 6th Avenue to 5th Avenue Section 1: Forms from corner of 6th Avenue East to 59 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Mounted Unit (forms on 6th Avenue above W. 45th Street) 2. U.S. Military Academy (West Point) Pipes and Drums 3. Grand Marshal Banner 4. Grand Marshal Tommy Flanagan (with family/friends ) 5. St. Andrew’s Color Guard 6. NTDNYC Banner 7. Edinburgh Academy Pipe and Drum Band 8. National Tartan Day New York Parade Committee 9. BARBOUR 10. U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) Pipes and Drums 11. VIPs: 12. Scottish Parliament/Politicians/U.S. Politicians 13. Visit Scotland Section 2: Forms from 59 West 44th Street to 37 West 44th Street 1. Mt. Kisco Scottish Pipes and Drums 2. St. Andrew’s Society of New York 3. New York Caledonian Club Pipe Band 4. New York Caledonian Club 5. New York Metro Pipe Band 6. American Scottish Foundation 7. Bucks County Scottish American Society 8. Stephen P. Driscoll Memorial Pipe Band 9. Clan Campbell 10. Daughters of Scotia 11. St. Andrew’s Society; City of Albany 12. Middlesex County Police and Fire Pipes and Drums 13. Shot of Scotch Dancers 14. Flings and Things Dancers - 1 - Section 3: Forms from 37 West 44th Street to 27 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Marching Band 2. CARNEGIE HALL 3. Carnegie Mellon Alumni 4. Clan Malcolm/MacCallum 5. Clan Ross of U.S. 6. Tri-County Pipes and Drums 7. Long Island Curling Club 8. -

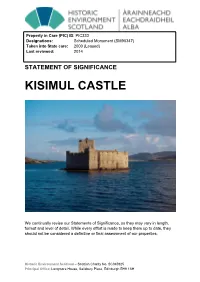

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck, Rùm Report No: HAS051202 Client The Small Isles Community Council Date December 2005 Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles December 2005 Summary This report sets out general recommendations and specific proposals for the development of archaeology on and for the Small Isles of Canna, Eigg, Muck and Rùm. It reviews the islands’ history, archaeology and current management and visitor issues, and makes recommendations. Recommendations include ¾ Improved co-ordination and communication between the islands ¾ An organisational framework and a resident project officer ¾ Policies – research, establishing baseline information, assessment of significance, promotion and protection ¾ Audience development work ¾ Specific projects - a website; a guidebook; waymarked trails suitable for different interests and abilities; a combined museum and archive; and a pioneering GPS based interpretation system ¾ Enhanced use of Gaelic Initial proposals for implementation are included, and Access and Audience Development Plans are attached as appendices. The next stage will be to agree and implement follow-up projects Vision The vision for the archaeology of the Small Isles is of a valued resource providing sustainable and growing benefits to community cohesion, identity, education, and the economy, while avoiding unnecessary damage to the archaeological resource itself or other conservation interests. Acknowledgements The idea of a Development Plan for Archaeology arose from a meeting of the Isle of Eigg Historical Society in 2004. Its development was funded and supported by the Highland Council, Lochaber Enterprise, Historic Scotland, the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage, and the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, and much help was also received from individual islanders and others.