The United Nations and Mandate Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Files, Country File Africa-Congo, Box 86, ‘An Analytical Chronology of the Congo Crisis’ Report by Department of State, 27 January 1961, 4

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/113873/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Marsh, Stephen and Culley, Tierney 2018. Anglo-American relations and crisis in The Congo. Contemporary British History 32 (3) , pp. 359-384. 10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 file Publishers page: http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 <http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 ARTICLE Congo, Anglo-American relations and the narrative of � decline: drumming to a diferent beat Steve Marsh and Tia Culley AQ2 AQ1 Cardiff University, UK� 5 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The 1960 Belgian Congo crisis is generally seen as demonstrating Congo; Anglo-American; special relationship; Anglo-American friction and British policy weakness. Macmillan’s � decision to ‘stand aside’ during UN ‘Operation Grandslam’, espe- Kennedy; Macmillan cially, is cited as a policy failure with long-term corrosive efects on 10 Anglo-American relations. -

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

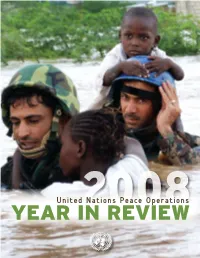

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

UNITED Nations Distr

UNITED NATiONS Distr. GENERAL SECURITY S/5053/Add.12 8 October 1962 COUNCIL ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/FRENCH REPORT TO THE SECRETARY-GENERAL FROM THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN THE CONGO ON DEVELOPMENTS RELATING TO THE APPLICATION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS OF 21 FEBRUARY AND 24 NOVEMBER 1961 A. Build-Up of Katangese Mercenary Strength 1. In recent months) information has been received from various sources about a bUild-up in the strength of the Katanga armed forces) including the continued presence and some influx of foreign mercenaries. 2. It will be recalled that after the Kitona Declaration) signed on 21 December 1961 (S/5038 L Mr. Tshombe) President of the province of Katanga) made it clear to United Nations officials that he proposed to seek a solution to the mercenary problem "once and for all". This undertaking was put in writing in a letter dated 26 January 1962 to the United Nations representative in Elisabethville (S/5053/Add.3) Annex I)) and was repeated in a second letter dated 15 February 1962. 3. However) in spite of this and further declarations of Katangese spokesmen along the same lines as the above-mentioned letters) evidence ''las forthcon,ing to United. Nations authorities that in fact the pledge with regard to the elimination of mercenaries from Katanga was not being kept. 4. The ONUC-Katanga Joint Corrmissions on mercenaries) set up to certify that all foreign mercenaries had left Katanga in conformity with Mr. Tshombe's decision) visited Jadotville and Kipushi on 9 February 1962) and Kolwezi and Bunkeya on 21--23 February. -

Questions Concerning the Situation in the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SITUATION IN THE CONGO (LEOPOLDVILLE) 57 QUESTIONS RELATING TO Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Laos, Mexico, FUTURE OF NETHERLANDS Nigeria, Panama, Somalia, Togo, Turkey, Upper NEW GUINEA (WEST IRIAN) Volta, Uruguay, Venezuela. A/4915. Letter of 7 October 1961 from Permanent Liberia did not participate in the voting. Representative of Netherlands circulating memo- A/L.371. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, randum of Netherlands delegation on future and Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory development of Netherlands New Guinea. Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, A/4944. Note verbale of 27 October 1961 from Per- Togo, Upper Volta: amendment to 9-power draft manent Mission of Indonesia circulating statement resolution, A/L.367/Rev.1. made on 24 October 1961 by Foreign Minister of A/L.368. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, Indonesia. Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory A/4954. Letter of 2 November 1961 from Permanent Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Representative of Netherlands transmitting memo- Togo, Upper Volta: draft resolution. Text, as randum on status and future of Netherlands New amended by vote on preamble, was not adopted Guinea. by Assembly, having failed to obtain required two- A/L.354 and Rev.1, Rev.1/Corr.1. Netherlands: draft thirds majority vote on 27 November, meeting resolution. 1066. The vote, by roll-call was 53 to 41, with A/4959. Statement of financial implications of Nether- 9 abstentions, as follows: lands draft resolution, A/L.354. In favour: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, A/L.367 and Add.1-4; A/L.367/Rev.1. Bolivia, Congo Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, Central African Re- (Leopoldville), Guinea, India, Liberia, Mali, public, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Nepal, Syria, United Arab Republic: draft reso- (Brazzaville), Costa Rica, Dahomey, Denmark, lution and revision. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

Protecting Civilians in the Context of UN Peacekeeping Operations

About this publication Since 1999, an increasing number of United Nations peacekeeping missions have been expressly mandated to protect civilians. However, they continue to struggle to turn that ambition into reality on the ground. This independent study examines the drafting, interpretation, and implementation of such mandates over the last 10 years and takes stock of the successes and setbacks faced in this endeavor. It contains insights and recommendations for the entire range of United Nations protection actors, including the Security Council, troop and police contributing countries, the Secretariat, and the peacekeeping operations implementing protection of civilians mandates. Protecting Civilians in the Context Protecting Civilians in the Context the Context in Civilians Protecting This independent study was jointly commissioned by the Department of Peace keeping Opera- Operations Peacekeeping UN of tions and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations. of UN Peacekeeping Operations Front cover images (left to right): Spine images (top to bottom): The UN Security Council considers the issue of the pro A member of the Indian battalion of MONUC on patrol, 2008. Successes, Setbacks and Remaining Challenges tection of civilians in armed conflict, 2009. © UN Photo/Marie Frechon. © UN Photo/Devra Berkowitz). Members of the Argentine battalion of the United Nations Two Indonesian members of the African Union–United Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) assist an elderly Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) patrol as woman, 2008. © UN Photo/Logan Abassi. women queue to receive medical treatment, 2009. © UN Photo/Olivier Chassot. Back cover images (left to right): Language: ENGLISH A woman and a child in Haiti receive emergency rations Sales #: E.10.III.M.1 from the UN World Food Programme, 2008. -

Degradation of the Environment As the Cause of Violent Conflict

Mohamed Sahnoun, Algeria. A thematic essay which speaks to Principle 16 on using the Earth Charter to resolve the root causes of violent conflict in Africa Degradation of the Environment as the Cause of Violent Conflict Mohamed Sahnoun has had a distinguished diplo- water and grazing land. Before, the fighting was with sticks; matic career serving as Adviser to the President of now it is with Kalashnikovs. That is the terrible thing about it. Algeria on diplomatic affairs, Deputy Secretary- There is no difference there; they are the same people. General of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and Deputy Secretary-General of the League of I am often a witness in my work of the linkage between the Arab States in charge of the Arab-Africa dialogue. degradation of the environment and the spread of violent con- He has served as Algeria’s Ambassador to the flicts. We tend to underestimate the impact of degradation of United States, France, Germany, and Morocco, as well as to the United the environment on human security everywhere. Repeated Nations (UN). Mr. Sahnoun is currently Secretary General Kofi Annan’s droughts, land erosion, desertification, and deforestation Special Adviser in the Horn of Africa region. Previously, he served as brought about by climate change and natural disasters compel Special Adviser to the Director General of the United Nations Scientific large groups to move from one area to another, which, in turn, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for the Culture of Peace increases pressure on scarce resources, and provokes strong Programme, Special Envoy of the Secretary-General on the reaction from local populations. -

Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary

ISSN 1088-2081 Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary Bruce W. Jentleson University of California, Davis Policy Paper # 27 June 1996 The author and IGCC are grateful to the Pew Charitable Trusts for generous support of this project. Author’s opinions are his own. Copyright © 1996 by the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation CONTENTS Defining Preventive Diplomacy ........................................................................................5 CONCEPTUAL PARAMETERS FOR A WORKING DEFINITION....................................................6 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN MEASURING SUCCESS AND FAILURE.....................8 The Possibility of Preventive Diplomacy .........................................................................8 THE PURPOSIVE SOURCES OF ETHNIC CONFLICT ..................................................................8 CASE EVIDENCE OF OPPORTUNITIES MISSED........................................................................9 CASE EVIDENCE OF SUCCESSFUL PREVENTIVE DIPLOMACY ...............................................11 SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................12 Possible, but Difficult.......................................................................................................12 EARLY WARNING................................................................................................................12 POLITICAL WILL .................................................................................................................14 -

ICV20 Lupant.Pub

Emblems of the State of Katanga (1960-1963) Michel Lupant On June 30 1960 the Belgian Congo became the Republic of Congo. At that time Ka- tanga had 1,654,000 inhabitants, i.e. 12.5% of the population of the Congo. On July 4 the Congolese Public Force (in fact the Army) rebelled first in Lower-Congo, then in Leopoldville. On July 8 the mutiny reached Katanga and some Europeans were killed. The leaders of the rebels were strong supporters of Patrice Lumumba. Faced with that situation on July 11 1960 at 2130 (GMT), Mr. Tschombe, Ka- tanga’s President, delivered a speech on a local radio station. He reproached the Cen- tral government with its policies, specially the recruitment of executives from commu- nist countries. Because of the threats of Katanga submitting to the reign of the arbitrary and the communist sympathies of the central government, the Katangese Government decided to proclaim the independence of Katanga.1 At that time there was no Katan- gese flag. On July 13 President Kasa Vubu and Prime Minister Lumumba tried to land at Elisabethville airport but they were refused permission to do so. Consequently, they asked United Nations to put an end to the Belgian agression. On July 14 the Security Council of the United Nations adopted a resolution asking the Belgian troops to leave the Congo, and therefore Katanga. Mr. Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General, considered the United Nations forces had to enter Katanga. Mr. Tschombe opposed that interpreta- tion and affirmed that his decision would be executed by force it need be.